Angels’ Ears

The first exhibition I saw in The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, in the 1980s, was Treasures of Norfolk Churches. The most beautiful piece was a head of an angel painted on glass and I had the poster of this fifteenth century angel on my office wall for many years.

Later, my wife and I were paying homage to Robert Marsham who recorded how nature changes over the seasons and so started the science of phenology in the eighteenth century. We traced him to St Margaret’s church in Stratton Strawless (poor soil, poor wheat, little straw) (1) where there was a small display of his work alongside the imposing memorials to his ancestors. Most of the remaining medieval glass was in the upper traceries of the windows but there, in the otherwise clear main light of the north aisle window, was the angel from the poster (visit the excellent: norfolkstainedglass.co.uk (2)).

Over many years of staring at this poster on a daily basis I had noted some peculiarities. First was the angel’s curly hair with a distinctive double S curl in the centre of the hairline; the second was the peculiar double tragus – the flap in front of the ear. Normally, this is a single-pointed prominence covering the opening to the ear. Abnormally, an accessory tragus can form as a smaller tag but the ear of the Stratton Strawless angel shows a more equal bi-lobing giving it a pie-crust appearance. A friend who spent time as a paediatric dermatologist never encountered a double tragus, indicative of it rarity.

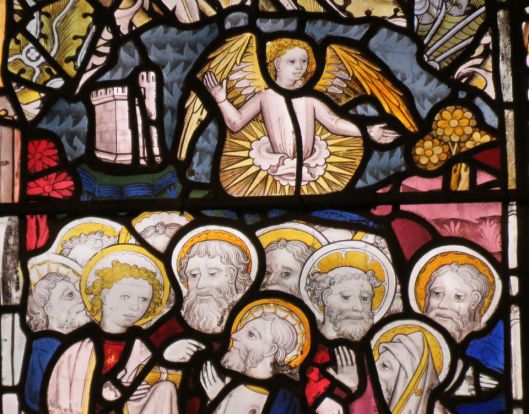

In another chance encounter I visited The Burrell Collection in Glasgow (3) and saw a very similar head in a 15th century stained glass panel attributed to The Norwich School (see also ref 4). Comparison with the Stratton Strawless angel shows they share the double tragus, the double S curl and evidently visited the same hair stylist. The noses are drawn with identical strokes of the brush, as are the philtrums (the double-lined channel between nose and mouth). But there is an overall cartoon-like quality to the Burrell saint that is missing from the softer Strawless angel. Whereas the Burrell saint has expression lines drawn at the corner of the mouth the more wistful appeal of the Strawless angel derives from the smoky shading at the edge of the mouth, giving the face a quizzical look somewhat reminiscent of the Mona Lisa.

Head of St John. St Peter Mancroft glass from The Burrell Collection Glasgow. Image reversed for comparison. Reproduced courtesy of Glasgow Museums.

Stratton Strawless angel. Note the double tragus in the ears of this and the figure above.

From the same family then but not identical twins. At this distance it is not easy to identify the artist but there are clues.

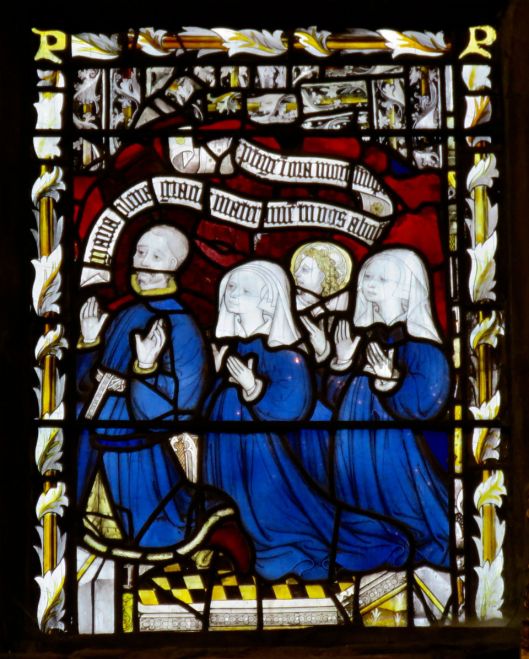

The Burrell glass (3) is attributed to the St Peter Mancroft church, Norwich. In 1450-55 Robert Toppes, a rich wool merchant, donated painted glass panels to this, Norwich’s ‘most prestigious’ parish church (4). An unknown proportion of the glass must have been destroyed by iconoclasts during the mid sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and the explosion of 90 barrels of gunpowder at the Royalist Committee House in nearby Bethel Street didn’t help. In 1647, during the Civil War, this ‘Great Blow’ killed or injured a hundred people (4,5). Apart from the panel now in The Burrell Collection, Glasgow, and two in Norfolk’s Felbrigg Hall (one of which is on loan in the Mancroft treasury) the rest of the surviving glass was gathered together in the east window in an apparently random fashion (4,6). Robert Toppes himself is depicted in the donor panel (below) along with female members of his family. The head of a curly-haired saint or angel replaces a lost third female head.

Robert Toppes and family in the donor panel of the east window of St Peter Mancroft, Norwich. The head of a blond saint/angel replaces one family member. Close inspection shows that Toppes’ ear is also painted with a double tragus.

Toppes (1405-1467) was probably Norwich’s wealthiest tradesman at the height of the city’s trading power, demonstrating the rise of the merchant class. He became mayor and was member of parliament four times. He built his own trading hall in King Street, adjacent to the River Wensum that was used to transport his fine cloths and wool for trade with the continent. This hall, then called Splytts, is now known as Dragon Hall after the carved dragon exposed amongst the roof timbers during restoration.

Dragon discovered in the roof timbers of Dragon Hall, King Street, Norwich. Courtesy of The Writers’ Centre

Records show that Norwich had been a regional centre for glass painting since at least the thirteenth century (7). The Toppes window was made by the prominent workshop of John Wighton (6,8) who was alderman when Toppes was mayor and whose workshop is likely to have been close to Toppes’ trading hall, Splytts. During his mayoralty Toppes paid for the windows of the Guildhall’s council chamber to be glazed by Wighton and on a tour of the Guildhall (highly recommended) it is possible to see generic similarities between figures in this and the Toppes window in St Peter Mancroft.

Stained glass window in Norwich Guildhall, painted by the Wighton workshop and funded by the mayor, Robert Toppes. Note Toppes’ coat of arms between the two angels.

For the Toppes window, David King in a magisterial book devoted to just this one window, identifies the styles of at least three painters (6, 7). In addition to Wighton himself, he suggests that the Master of the Passion window may have been his apprentice William Moundford who came from Moontfort in Utrecht, underlining the close links between Norfolk and the Low Countries. William’s wife Helen was – perhaps surprisingly considering the date – also a glazier in Wighton’s studio and she is thought to have made a contribution to the Toppes window. Their son John was also apprenticed to Wighton in 1446 and became head of the workshop in 1458.

Panels from St Peter Mancroft’s ‘Toppes’ window. All visible ears display the double tragus.

On a recent visit to The Metropolitan Museum, New York, I saw fifteenth century stained glass attributed to Gloucestershire (9), in which the apostles also had the double tragus, although this bunch of ruffians looked nothing like the angelic Stratton Strawless head. So by itself this facial feature cannot be considered diagnostic of a particular artist or school. Indeed, angels painted on the wooden panels of the beautiful rood screen of St Michael, Barton Turf, Norfolk have the double tragus, showing that this trait was not confined to glass painting.

Angel painted on rood screen of St Michael Barton Turf. The angel’s ear shows the double tragus.

By comparing more than one facial trait it should be possible to further define the Strawless glass painter. A tour around Norfolk, based on the brilliant Hungate glass trails (10), reveals other saints and angels by the Wighton workshop and by using imaging software it was possible to overlay their images onto the Strawless angel. Below, these reunited fragments of an angel’s head from Warham St Mary share the double tragus and double-S curl with the Stratton Strawless angel.

Head of angel, Warham St Mary’s Norfolk

The transparency of this image was increased and the face overlaid onto the Strawless angel.

Overlaying the heads of the Strawless and Warham angels

The positions of the nose, ear and mouth of the two angels coincide pretty well as do the eyes, despite the lead strip across the Warham figure. Only the Warham angel’s more prominent jaw is significantly out.

Another angel with an enigmatic smile, and which rivals the beauty of the Strawless head, can be seen at All Saints Church, East Barsham, Norfolk. This musician wears ‘feather tights’ as worn in medieval mystery plays.

Angel, All Saints East Barsham, Norfolk

Below, overlaying the semi-transparent heads of the Strawless and East Barsham angels reveals an exact coincidence between the alignment of ears (with double tragus), the angle of the nose, position of the pupils, size and shape of the mouth as well as the overall shape of the face, even the scratched shading inside the upturned collar.

Overlay of the East Barsham and Stratton Strawless angels

The exactness of this coalignment strongly suggests that the two heads originated from the same workshop. However, different members of the shop may have used the same template or cartoon at different times yet produced identifiably different results, as with the various artists of John Wighton’s workshop thought to have painted the Toppes window. And remember that not all those figures by the Wighton workshop had the double tragus. It seems probable, therefore, that the Strawless and East Barsham (and Bale) heads are by the same artist.

So who was that artist? After more than 500 years there is little to go on (see 8). David King, the eminent authority on Norfolk stained glass mentions that in 1473 John Marsham left a bequest in his will for the glazing of Stratton Strawless north window (11). There is no guarantee that the Strawless angel was part of the bequest but if it were this would date the angel to the 1470s. In this case John Wighton died too early to have painted the angel’s head (1458). There is record of William Mundford’s will in 1457 so he, too, may have preceded the painting of the angel. However, his son John, who became head of the Wighton workshop, died in 1481 and could have painted the piece. What does seem clear is that the cartoon on which the Stratton Strawless angel was based originated in Norwich’s Wighton workshop and was adapted by its various artists over several decades.

©2015 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- norfolkchurches.co.uk

- norfolkstainedglass.co.uk

- The Burrell Collection, Glasgow. Asset number 45.92_01

- Matthew, R. (2013) Robert Toppes: Medieval Mercer of Norwich. Pub, The Norfolk and Norwich Heritage Trust.

- http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/social-innovation/norwich-in-the-civil-war.html

- King, D. J. (2006) The Stained Glass of St Peter Mancroft, Norwich, CVMA (GB), V, Oxford.

- Woodforde, C. (1950) The Norwich School of Glass-Painting in the Fifteenth Century. Pub, Oxford University Press.

- King, D. (2004). Glass Painting. In, Medieval Norwich eds C. Rawcliffe and R.Wilson. Pub, Hambledon and London. pp121-136.

- http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/463580?rpp=30&pg=2&ft=gloucestershire&pos=53

- http://www.hungate.org.uk

- King, D.J. (1974)Stained Glass Tours Around Norfolk Churches. Pub, The Norfolk Society.

Fascinating, it will make visiting Norfolk churches so much more interesting. Keep me in touch with any further discoveries.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the kind comment. Although my next posting will be on Thomas Jeckyll and the Aesthetic Movement there might be a little on churches

LikeLike

Real insight into an interesting subject. I wonder if their is descriptive name for the study of angels ears.? theo

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry for the delay Theo, I needed to digest Christmas. The answer is, Angelugology

LikeLike

What a fascinating blog! I love the attention to detail you pay to these beautiful decorations that may otherwise remain under valued and even lost in history. Norwich does have such a rich history, it’s an amazing city! I look forward to your next post.

LikeLike

Pingback: Entrances and Exits (Doors II) | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The Norwich coat of arms | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Faces | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

I’m ‘collecting’ Norfolk angels on my camera at the moment and found this illuminating and very interesting. Just checked out the Cawston stained glass and the double tragus is evident on one of them. I think the one at Bawburgh has one too though this sis debatable – it dooes resemble the Stratton Strawless one. The Virgin in the Nativity holding Jesus also has a double tragus as does the angel above her and to the right and also the one above the apostles. I also have a book out on Norfolk medieval carving (mainly bench ends..unashamed plug for From Bears to Bishops here). Great article.

LikeLike

Hi Paul,

Once noticed, that double flap on the ear (tragus) becomes fascinating, doesn’t it? However, it isn’t an absolute indicator of Norwich School glass in general; it isn’t used by all the glass painters in St Peter Mancroft. Woodforde lists Cawston as being Norwich School based on the rows of ‘ears of barley’ used by NS painters to depict wood grain. Please let me know if you have further insights.

BTW I love your photographs of Norfolk church carvings (www.mascotmedia.co.uk). Thank you for following. Reggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Norfolk Botanical Network | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The angel’s bonnet | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Was excited about this as I have a subtle bifurcation of the tragus — and I’d never really been conscious of it before.

LikeLike

Thank you for telling me, I’ve not encountered a double tragus in real life. You must feel blessed. In the company of angels.

LikeLike

Yes, it’s a very subtle one compared to the images online. I wouldn’t want it full-on, but this makes me feel quietly divine!

LikeLike

Pingback: Norfolk Rood Screens | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH