I have lived in Norwich for ages, mostly on or around the Unthank Road, and became fascinated by the name and the distinctive style of housing found in this area.

“What’s in a name?” The name first occurs as William de Unthank (or Onthank) of Unthank Hall, Northumberland (ca 1231). Several explanations have been offered for the name [1].

- Unthank = thankless or unthankfulness

- the amount of land granted to a Saxon thane, or to a Scottish chieftain, each recipient holding “a thank” or one thane’s holding – about the size of a village or hamlet. A thane would be known as a “one thank man” and un/on thank was originally confined to the borderland between England and Scotland [2].

- Old English for land held without leave by squatters. Or common land annexed by outlaws, e.g., the border reivers.

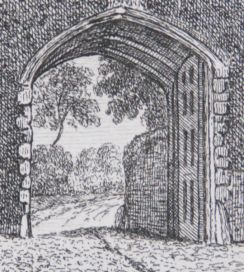

Unthanks came down from the north to Norwich in the 17th century; others came in the 18th century [1] and became prosperous businessmen. In 1793 William Unthank moved outside the walls of the congested medieval city. He bought land in rural Heigham, just outside St Giles’ Gate, over a century before St John’s Catholic Cathedral was built (ca 1910).

The houses at the end of Upper St Giles Street today (left) can be identified in John Ninham’s engraving of 1792 (right). The catholic cathedral (left) now stands where open fields could once be glimpsed through St Giles’ Gate [2].

Open countryside could be seen through St Giles’ Gate in 1792

The family amassed about 2500 acres of land, including farmland to the south and west of Norwich as well as their Heigham Estate that stretched from St Giles’ Gate southwards to Eaton (aka Waitrose). This meant that when William’s son and heir, Clement William Unthank, went courting the heiress of the Intwood Estate, Mary Anne Muskett, he could ride for most of the journey without leaving family land [1,3, 4].

At first, Clement William and Mary Anne lived in Norwich at ‘Unthanks House’ near modern-day Bury and Onley Streets but in 1855 they moved to her childhood home, on the Intwood estate, at the outskirts of the city [3, 4]. (‘Onley’ was a family name of the Musketts).

Intwood Hall

Unthank Road and the New City The Unthanks had already begun to sell off parcels of their Heigham Estate for housing but this was accelerated when Clement William moved out to Intwood in 1855. This helped the spread of the New City. The old city itself contained unsanitary medieval courts or yards [5] that had to wait until the C20th for demolition or improvement but Clement William’s buildings were of a higher standard. As the New City continued to be developed it became subject to the more enlightened bye-laws and acts that arrived in the latter half of the C19th [6,7].

Originally, ‘Unthanks Road’ had been known as Back Road – a private sandy lane on the Unthank estate [1]. But between 1849-1870, when some of the early ‘Unthank’ streets (such as Essex, Cambridge and Trinity Streets) were built, Unthank Road became the main axis to which they were attached.

Unthank Road when it was still little more than a lane. Looking up towards the city with the junction to Park Lane to the left, just beyond the pub sign. www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

Norwich: “No place in England was further away from good building stone” Stefan Muthesius [8]

The Normans had to ferry stone for their cathedral from Caen in Normandy, much of the medieval city was built of flint, but the new city was to be built of brick and slate. This was helped by the arrival of the railways, which also allowed easier access to slate from North Wales. Clement William Unthank closely regulated the appearance of the estate and builders had to sign restrictive covenants stating how brick and other building materials were to be used [5, 6].

- the building to be faced in good white brick and roofed in good slate or tiles

- that doors should be arched in gauged brick

- that no building be placed beyond the building line

- that no gable peak be allowed to the front of the house

- that no porch or projection should extend more than 18 inches from the building line unless agreed by Clement William Unthank

Uniform, flat-fronted terraces of a high standard were therefore assured across Unthank’s Heigham estate, as seen in Trinity Street below. Suffolk White bricks were known to have been used as were ‘Cossey Whites’ from the nearby village of Costessey. I lived for some years in Cambridge with its plain-fronted terraces of white brick and it was this that had drawn me to the Unthank estate.

Evidently, workers leaving the land for the city could be more economically housed in uniform terraces compared to the individuality of rural cottages. These modest houses may well have been a much diluted version of the Palladian houses and terraces seen by the upper classes on their Grand Tour. In Norwich, the use of white brick and arched doorways are likely to have been influenced by the expensive white bricks used for country houses like William Kent’s Holkham Hall in north Norfolk and John Soane’s Shottesham Park, which was only five miles south of Norwich – a short horse ride from CW Unthank’s new home at Intwood [7,8].

The widespread use of arches made of ‘gauged’ bricks fired in specially-shaped concentric templates, and the fineness of their pointing, is thought to be characteristic of Norwich [8, 9]. Nowadays, generations of owners have personalised the houses by painting over the gauged brick and adding porches that would have been frowned on by Clement William Unthank. This British reaction against uniformity was celebrated in the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band’s ‘My pink half of the drainpipe’.

Newmarket Street where some degree of variation was allowed, with white gauged bricks alternating with red brick rarely seen on front elevations

The recessed inner arch gives variation without breaking the building line; seen here in the former Kimberley Arms being refurbished in 2016. Compare the fine pointing between the arched gauged bricks with the thicker mortar in the horizontal courses.

However, compared to the gentility of the front elevations the backs of buildings were generally constructed of cheaper materials.

Earlham Road front: Recreation Road behind. The frontage is built from Suffolk White bricks and slate: the rear from Norfolk Red bricks and pantiles (based on 6).

The use of cruder materials to the back has been referred to as a Queen Anne front and a Mary Anne behind – as in the popular song: (6)

Queen Anne Front (lyric Robert Schmaltz)

When Great Grandfather was a gay young man

And Great Grandmother was his bride

They found a lot, a jolly little spot

Over on the old North Side

It sloped down toward the river, from River Avenue

Great Grandma said that it would give her

Such a lovely view

So they took a look in Godey's Ladies Book

To see what they could find

And they found a house, a jolly little house,

With a Queen Anne front

And a Mary Anne behind.

Larger houses for the middle classes were built along Unthank Road itself whereas the smaller houses for artisans were situated in the streets behind. As part of the Unthanks’ urban planning, trade was prohibited from the terraced houses so purpose-made public houses were confined to corner locations on back streets (e.g., York Tavern, Rose Tavern, Kimberley Arms and Unthank Arms).

The Unthank, formerly The Unthank Arms

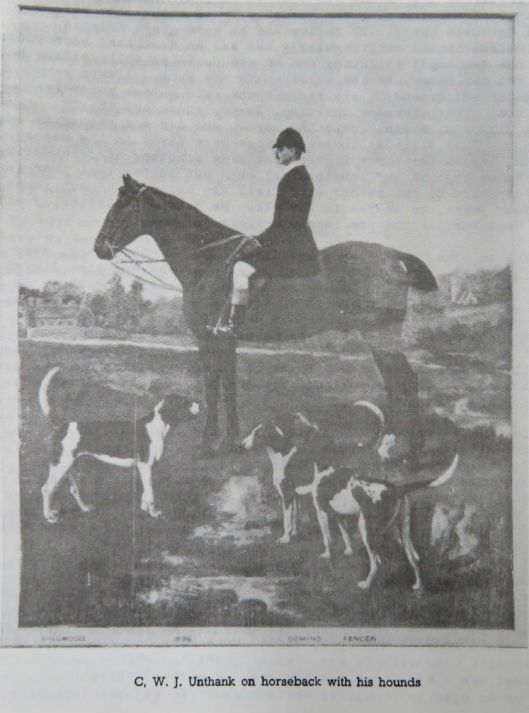

So who was Colonel Unthank? Clement William Unthank sold much of the land his father had amassed on the Heigham Estate. His son, Clement William Joseph, continued to sell parts of the state for building but the effect is said to be less good [7]. CWJ is the first of two Colonel Unthanks in this article. He was a captain in the 17th Lancers and Lieutenant Colonel of the 4th Volunteer Battalion of the Norfolk regiment [1, 4].

Clement Wm Joseph Unthank with his hounds Ringwood, Domino and Fencer [from 1]

CWJ Unthank’s son was John Salusbury Unthank (below) who continued to develop the Heigham Estate into the C20th. He served in The Boer War and World War I, where he fought at The Somme and Ypres. So John Salusbury Unthank is the second Colonel of this article. Anecdotal evidence of him survives into the C20th and there may be some who still remember him [1,3,4].

A hunting man [1]

Colonel Unthank would stride into Intwood church where the service would not start until he’d taken his place. Once, when he stood up in church to take off his mackintosh the congregation behind him also stood up, telling us something of his position in the community [3]. Imagine.

In addition to the Unthank family the area was also developed by others, notably the Eaton Glebe estate [7]. Their restrictive covenants also ensured quality and some uniformity e.g., all parts of buildings exposed to view to be faced in good red brick [7]. But in detail the different use of materials – not just red instead of white brick but different treatments of bays and porches – gave this area a different texture as can be seen along College Road.

The entire area to the south-west of the medieval city is now known as The Golden Triangle, beloved of estate agents. The borders of this vibrant area can be drawn in various ways but the Triangle’s online organ, The Lentil (“Our finger on your pulse”), [10] gives this authoritative version:

The Golden Triangle (http://the-lentil.com).

The Wall

I can’t remember who told me that this piece of tall wall was the last remnant of the Unthank Estate, but it has adopted the status of urban myth. The wall shelters No 38 Unthank Road from traffic and is at the junction with Clarendon Road.

‘The Wall’, at the junction of Clarendon and Unthank Roads

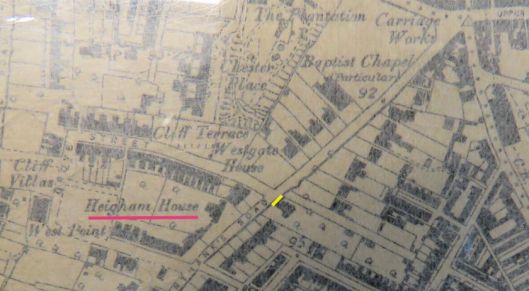

In the early C19th, according to Reverend Nixseaman [1], William Unthank lived in Heigham House and he places this directly opposite the stable wall above. However, it is claimed elsewhere [11] that the family estate was further down Unthank Road, too far away for ‘the wall’ to be part of their stables.

Tithe Map of Heigham 1842 (Norfolk Records Office). Red star = Heigham House/Lodge; blue star = ‘Unthanks House’; arrow = ‘the wall’ on Unthanks Road.

So who did live opposite the wall? Consulting the tithe records for 1842 reveals that the brewer Timothy Steward lived here; he is shown as the owner of Heigham House (sometimes called Lodge) while William’s heir, Clement William Unthank, is recorded as living with family and servants further down the road near modern-day Bury Street (blue star).

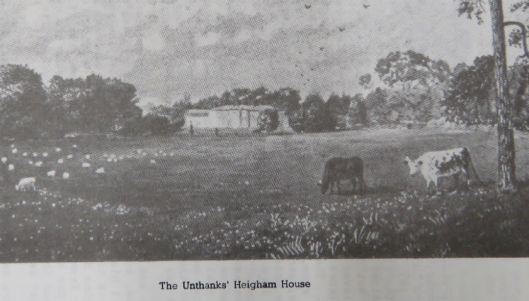

But back to Reverend Nixseaman, he wrote his book about the Unthanks [1] in 1972 with the assistance of William Unthank’s descendants and was familiar with minutiae such as the names of CWJ Unthank’s three dogs. In his authorised version he asserted that in 1792 Clement William’s father, William, moved into a newly-built and spacious home named Heigham House, set in its own parklands.

Heigham House (red) is bookended by today’s Clarendon and Grosvenor Roads with ‘the wall’ opposite (yellow). [6″ OS map 1887]

The OS map confirms that in 1887 there was indeed a Heigham House opposite the wall although by then the encroaching terraces left little room for the ‘parkland’ illustrated in Nixseaman’s book (below). So which version is correct?

Heigham House ca 1800 [1]

The search for the location of the Unthanks’ house continues with two further posts and a book that contains much material – and Unthank photos – not included in the blog posts. See:

https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/04/15/colonel-unthank-rides-again/

https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/07/15/the-end-of-the-unthank-mystery/

Book available from Jarrolds book department and City Bookshop, Norwich. Price £10

©2017 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- Nixseaman, A.J. (1972). The Intwood Story.ISBN 0950274208, Norwich. (Available from the Heritage Centre, Norwich Library)

- Read the excellent article by Norwich City Council on St Giles Gate http://www.norwich.gov.uk/apps/citywalls/20/report.asp

- A History of Intwood and Keswick (1998), by Cringleford Historical Society. ISBN 0953011623. Held at The Heritage Centre, Norwich Library.

- Memories of Intwood and Keswick (2001) by Cringleford Historical Society. ISBN 0953011631.

- Holmes, Frances and Michael (2015). The Old Courts and Yards of Norwich. norwich-yards.co.uk

- Muthesius, Stefan. (1982). The English Terraced House. Yale University Press.

- O’Donoghue, Rosemary. (2014). Norwich, an Expanding City 1801-1900. Pub, Larks Press ISBN 9781904006718.

- Muthesius, Stefan. (1984). Norwich in the Nineteenth Century. Ed, C. Berringer. Chapter 4, pp94-117.

- www.norwich.gov.uk/Planning/documents/Heighamgrove.pdf – an excellent discussion of the Unthank/Heigham Estate.

- The Lentil. The Golden Triangle’s wittiest online magazine http://the-lentil.com

- heritage.norfolk.gov.uk

Thanks to: the staff of The Heritage Centre in Norwich Library and of the Norfolk Records Office for their cheerful help; Tom Tucker of The Lentil for drawing the Golden Triangle map; and Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk for permissions.

Thanks Reggie, for a thoroughly researched insight into Victorian Norwich.

LikeLike

Thank you Theo.

LikeLike

Fascinating – thank you

LikeLike

Thank you Andrea for the support.

LikeLike

Fascinating blog and a superb local resource, thank you. I can’t help but feel that this material would look great in printed form too, perhaps published as a booklet of some kind ? The piece on the Golden Triangle was especially interesting – but horror of horrors, the Unthanks were Northeners ! I can’t help but feel that readers of The Lentil need to be told !!!

LikeLike

I am a great admirer of The Lentil so your comments are much appreciated Tom. Yes, ‘Unthank’ seems to be well northern. Not wanting to worry you but I see that The Unthank Arms has taken lentils off their menu and replaced them with mushy peas and ciabatta raspings!!

LikeLike

Great to see local history presented so interestingly and creatively! I think we may indeed be Northerners! North of the Watford Gap and Norwich has the most badass mushy pea stall on the market…proof!

LikeLike

Thank you Susie but at Unthank Towers we have a preference for the petit pois.

LikeLike

Another great post – Colonel Unthank sounds like a formidable character (esp. with all the mac business!)

LikeLike

Hi Cat, yes, the Unthanks must have been a formidable family.

LikeLike

I too have in ingrained in my psyche that the wall opposite Clarendon Road is the last bit of Unthank – stables wall. Prob got a reference to it somewhere.

LikeLike

How (potentially) exciting. Would really like to see that reference Terry.

LikeLike

You have the reference yourself Reggie – its in the Nixseaman book you quote … see p107 and 120-1. It’s not impossible to have some stabling up there given that the whole park came from where the gaol used to be and it’s opposite Heigham Park (not to be confused with them modern day school)/ Lodge )park or lodge dependent upon which source you use). Of course,the whole potential confusions around Heigham Lodge/ Park and Unthank’s House are probably worth a couple of hours in a parallel universe! Rev Nixseaman does seem to be a bit of a scholar so I wouldn’t write his suggestion off too quickly. It’s certainly worth more than simply a quick dismissal as “local tradition”.

LikeLike

Hi Terry, I do favour the idea that William Unthank lived in Heigham House at the Clarendon/Unthank Road junction but it hasn’t been possible to corroborate the account in Nixseaman’s multiverse. He says William’s son Clement William lived in Heigham House from 1837-1857 but poll records show CW lived down the road (near Bury St) in ‘Unthank’s House’ over that period while the brewer Timothy Steward lived in Heigham House. Need to find a wormhole between these paradoxical worlds showing that William Unthank lived in HH until about 1830 before selling it to Steward. I’m working on it.

LikeLike

Very good read, what I’d give to go back to the mid-1800’s to have a look around

LikeLike

There’s a link to Norwich in the Bonzo mention. Dave Clague played bass for them early on, I believe including Urban Spaceman, he went on to become a teacher and set up DJC records releasing various stuff from people including stuff from himself and Coyne. He lives Northside in my neck of the woods amidst the rows of shoe factory-fodder houses. Great stuff by the way.

LikeLike

Hi Nick, I remember seeing Roger Ruskin-Spear and his Exploding Trouser Press whirling a tube around his head (or was it Legs ‘Larry’ Smith) during a live version of Urban Spaceman. PS Where are the shoe-factory houses?

LikeLike

Like you I have been interested in the Unthank name, partly because I am aware of a remote family connection. I have here a few letters from Harriet Nichol, later Mrs John Bulman to her cousin Sarah Unthank 1834, and to her Aunt Unthank 1842. If it would be of interest for you to see these do contact me. Your interest would provide welcome motivation for me to look into this a bit more.

LikeLike

Very informative read, thank you from a resident of the Golden Triangle on Warwick Street.

LikeLike

Thank you for the kind comments, Edwina. The GT is such an interesting community.

LikeLike

Hi Unthanks! I had to comment as I nearly fell over when I saw Unthank and Muskett mentioned in the same article. The families are very (very) distantly related! My Musketts are from Pentney in 18th/19th centuries. Thomas Muskett had a child (illegitimate) with Elizabeth Hensby and is recorded in the bastardy records as paying monthly towards his upkeep. The child Thomas Muskett Hensby (b.1814 in Shipdham) is my great great great granddad (maybe there’s another great – I haven’t got the info to hand). William and Mary Hinsby/Hensby (nee Burrell), Elizabeths parents, and family,lived in Castle and South Acre. Later, Thomas and Mary Ann (nee Reed) Hensby’s son Elijah (b.1847 Shipdham)) moved to Yorkshire where he married Rebecca Smith. Their eldest son William Hensby (b. 1881 in Aldwark) married Louisa Robertson. Being shepherds and agricultural workers they lived in tithe/tied “cottages”, moving yearly to where the work was as the landlord would decrease the wage and increase the rent in the second year and finally settled in Wakefield, the city where I was born. My Nana’s sisters grandson, unfortunately not a Hensby by name, married an Unthank from the North East! There’s at least one village in the Pennines called Unthank – so named as it was an unthankful task to mine the iron ore and live in awful conditions, not that dissimilar from the makeshift towns of the north American Goldrush – apart from there was no potential striking-it-lucky!

Anyway, I hope that was interesting and maybe helpful to some people. If anyone knows anything about the Hensby family, especially the whereabouts/location of Cankerweed Common, Shipdham ( also as Canker Wheal; being caterpillar infested land) possibly The Green House on Cankerweed Common; I would be really grateful to them for contacting me or leaving a comment. Thanks very much.

LikeLike

Dear Vicky, Thank you for that fascinating piece of family history. I’ll let you know if anyone is able to enlighten you. Reggie

LikeLike

Hi Vicky. I am a direct descendant of Thomas Muskett Hensby. He is my 4th great grandfather. I got stuck when I got as far back as the bastardy order and only just got hold of those records. No wonder I couldn’t get any further back as the Muskett name seems tricky to trace. The Unthanks link here has been great. Would be interesting to see where our ancestry lines up.

LikeLike

Thanks Rob, I’ll pass on your comments to Vicky if that’s OK.

LikeLike

If of interest,I am a northerner,living at York,whose forebears lived at Kippax,west Yorkshire until my grandfather moved to Castleford,close by where my father and myself were born.

LikeLike

Thanks for getting in contact Geoffrey. I once saw a map showing that most Unthanks came from the north-east. Is that your experience? It certainly is a distinctive name.

LikeLike

Hi Reggie, Very interesting info.I am an Unthank(Curtis) in the USA..Ohio..Always heard we might be tied someway to the UK.SOUNDS THAT WAY. Enjoyed the history lesson.

Curtis Unthank

LikeLike

Hi Curtis, I bet there’s a pretty straight link between you and the English Unthanks – such a specific name. I know of an Australian branch of the family who keep in touch and with a little digging you should be able to find a family network for the US branch. Good luck in your search, Reggie

LikeLike

Pingback: The Norwich Banking Circle | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH