Tags

Arts and Crafts Movement, CFA Voysey, Edwin Lutyens, EW Godwin, Norman Shaw, Norwich buildings, Norwich houses, Queen Anne revival

Following the explosion of terraced-house building in the latter part of the C19th it was perhaps the Arts & Crafts movement that had the greatest influence on the detached and semi-detached houses that were then built at the edges of a still-expanding Norwich.

The Arts & Crafts Movement took its name from The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society (1888). Its members believed in the fusion of art and craft and held to the principles of craftsmanship and truth to materials expounded by William Morris. Morris was revolted by Victorian mechanisation and started a moral crusade in search of a purer, craft-based way of living. His Red House, designed by his friend Philip Webb, represented a transition from full-blooded Gothic to a romanticised pre-industrial version.

The Red House, Bexleyheath. Built ca. 1860 (Ethan Doyle White)

Morris despised much of contemporary design so he decorated the house with help from friends such as the Pre-Raphaelite artists Rosetti and Burne-Jones. This was expressed in his famous motto: “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” At about this time Morris formed his own design company, Morris & Co, which became “the furnishing wing of the Pre-Raphaelite movement” [1].

William Morris’ wallpaper design ‘Fruit’ (1864) still in production today (william-morris.co.uk)

Richard Norman Shaw was a contemporary of Webb’s. Although both architects adhered to Morris’ principles of locally sourced materials and craftsmanship both diverted from the Gothic to develop a vernacular alternative. Webb developed Old English design but by the 1870s this had given way to a trademark ‘Queen Anne’ Revival style [2]. This Arts & Crafts style was not a slavish return to the architecture from Queen Anne’s age (early 1700s) but a mixture of influences: Dutch, Flemish, French, Robert Adam and the Japanese-influenced Aesthetic Movement. Added to this was an English Renaissance style based on Christopher Wren (the ‘Wrenaissance’) in which red brick was favoured over the white stone (or brick) of classical Palladian buildings [3]. As well as red brick, red tiles and terracotta panels became the materials of choice during the Queen Anne Revival.

A celebration of red brick, Ipswich Road 1878

In Shaw’s version of Queen Anne, multi-paned windows with crisp white glazing bars were a distinguishing feature. By the time this had filtered down to the general building trade – which is when we see it in the provinces – a common formula for windows was for the small panes to be restricted to the upper part with larger panes of plate glass at the bottom [3].

‘Queen Anne’ in Unthank Road

Bedford Park Estate in Chiswick London occupies an important place in the Arts & Crafts canon because it provided the model for the late nineteenth century suburb and led to the Garden City Movement [1].

The Tabard in Bedford Park; a ‘pioneer’ Queen Anne pub designed in 1877 by R Norman Shaw. Courtesy architecture.com

Initially, EW Godwin – who anticipated modernism with his stunning Aesthetic, Japanese-influenced sideboard – had designed small detached and semi-detached houses but these were not well received and so Norman Shaw was recruited to provide further designs.

EW Godwin was heavily influenced by Japanese design as in this sideboard 1867-1880 (copyright Victorian and Albert Museum). A bit off-piste but a favourite of mine

The Ballad of Bedford Park (below), although satirical in intent, gives an idea of the totality of the Arts & Crafts movement and shows how its spirit invaded all parts of the art-conscious middle-class home.

With red and blue and sagest green

Were walls and dado dyed

Friezes of Morris there were seen

And oaken wainscot wide

Now he who loves aesthetic cheer

And does not mind the damp

May come and read Rosetti here

By a Japanese-y lamp.

(St James’s Gazette, 1881)

Two other architects had a major influence on Arts and Crafts style. The first was Charles Francis Annesley Voysey [4]. Characteristically, he employed large sweeping roofs set above horizontal ribbons of windows. Walls were covered with his trademark white-painted roughcast. Even when he wanted to use local materials, clients insisted on his popular roughcast [5]. This coating, which John Betjeman [6] thought ‘dematerialised’ the surface of a house, provided local builders with an inexpensive shortcut to an Arts & Crafts style unburdened by any underlying philosophy.

Voysey designed this house for his father 1896. Photo FCG Dimmick (architecture.com)

Voysey took a child-like approach to his work and used obvious imagery like hearts as cuts outs on woodwork and as a recurring motif in his ironwork – another shorthand for readers of weekly trade journals like The Builder.

‘Hearts of Oak’ chair for Liberty with heart-shaped cutouts.

Edwin Lutyens was another key figure in the Arts & Crafts movement. He enjoyed a long professional partnership with the garden designer Gertrude Jekyll. In 1896 Lutyens built Munstead Wood. Miss Jekyll clearly wanted a house rooted in tradition (“Arts and Crafts simplicity was the note” [7]) for she specified something “designed and built in the thorough and honest spirit of the good work of old days” [8].

Munster Wood by Edwin Lutyens for Gertrude Jekyll (architecture.com)

His early designs involved huge chimneystacks in Norman Shaw’s Old English style, horizontal bands of leaded casement windows, and great sweeping tiled roofs. These catslide roofs could come down to door level leaving the first floor bedrooms to protrude via large gables [1]. A Norfolk example can be seen at Overstrand Hall:

Lutyens’ Overstrand Hall (overstrandparishcouncil.org.uk)

… and while we’re in Overstrand here’s a surprising Lutyens building:

Overstrand Methodist Church designed by Edwin Lutyens

Lutyens was famously playful and loved verbal as well as visual puns, such as shaping brackets to the silhouette of the client. In one version of a story he is claimed to have said to a bishop toying with a portion of fish, “I suppose that’s the piece of cod that passeth all understanding.”

George du Maurier, Punch (1895)

Although Arts & Crafts architecture became a popular movement its most iconic buildings were mainly architect-designed one-offs for the wealthy. Amongst the important examples in Norfolk is Home Place, now known as Voewood, at Kelling near Holt. Its architect was ES Prior, the co-founder of the Art Workers’ Guild and “perhaps the most brilliant of all Shaw’s pupils” [1]. Here he built a butterfly house with its obliquely projected wings. Building material dug from what is now the sunken garden was used to make the inner core of concrete to which the larger excavated flints were applied [7].

ES Prior’s Home Place/Voewood with sunken garden at front. (voewood.com)

Two other butterfly houses are found in Norfolk: Kelling Hall by Sir Edward Maufe and Happisburgh Manor by Detmar Blow and Ernest Gimson. Although they were built in the Arts & Crafts spirit their singularity (and cost) ensured that butterfly houses did not become models for a more widespread Arts & Crafts style.

In Norwich, at number 24 Tombland is St Ethelberts designed by EP Willens and built in 1888. It throbs with A&C references: red brick, plaster swags between curved oriel windows, roughcast, dormers set in a tiled hipped roof. The design of this remarkable house is said [9] to owe a debt to Norman Shaw (“wildly Norman Shavian”) but the original on which this was surely based is not too far to find.

St Ethelbert’s No 24 Tombland, Norwich (1888)

The Ancient, or Sparrowe’s, House Ipswich 1670 (Photo: Andrew Dunn)

‘The Sparrowe’s House’ type of oriel (curved sides, flat front, leaded lights with a central arch) is recognised to be one of three Old English window designs used by Norman Shaw [3]. However, these two East Anglian buildings, with oriel windows joined by botanical swags, are so similar that it seems likely that the Norwich architect had first hand knowledge of the Ipswich building as well as of Norman Shaw’s pattern book .

Swags are found on another Norwich building …

… St Mary’s Croft in Chapelfield, built in the Tudor Revival style.

St Mary’s Croft 1881

St Mary’s Croft is a symphony of red brick, from the concave/convex ovals on the gateposts – a humorous example of the bricklayer’s art – to the floral panels of moulded brick. I remember when it used to be my dentist’s surgery.

One of my favourite buildings in Norwich is Tower House at the junction of Newmarket and Kingsley Roads.

Tower House, Kingsley Road, Norwich

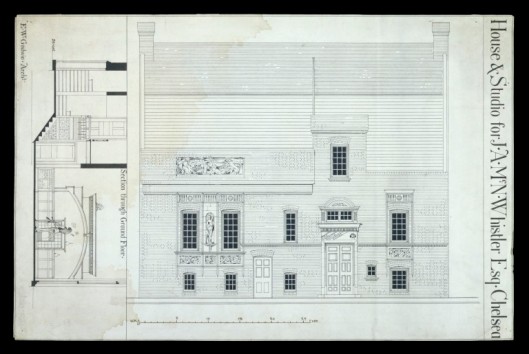

Tower House is generically Arts & Crafts with roughcast walls and a romantic tower capped by an ogee lead roof. What I find more interesting is the simplicity and asymmetry of this elevation – its effect depending on the massing of ten different windows (plus fanlight) in eight different styles. This irregularity echoes one of the most iconic buildings of the Arts & Crafts movement: the White House by EW Godwin. The irregular composition of its windows – really a blocking out of shapes on a flat surface – is thought to reflect Godwin’s fascination with Japanese art and the way it embraced asymmetry [3].

The White House in Tite St, Chelsea, designed by EW Godwin for James Whistler (1878). Demolished in the 1960s.

Below, in Limetree Road, Norwich is this archetypal Arts & Crafts house by Percy Morley Horder. (His students couldn’t resist a Spoonerism and called him Holy Murder). He went on to design Nottingham University for Jesse Boot (the Chemist). This part of the building (1908) containing the carriage arch, covered in roughcast, is pure Voysey.

In 1879-1886, at the time of the first Ordnance Survey, the parts of Newmarket and ‘Unthanks’ Road south of the present Mile End ring road were mainly open fields and nurseries. Their development around 1900 shows how various Arts & Crafts features were absorbed by local builders to make the Edwardian house, some 40 years after Morris et al had tried to find an honest vernacular style.

These semi-detached houses on Eaton Road were designed by architects Postle and Webster in 1906 for the builders Podd and Fisher of Aylsham Road.

Eaton Road, Norwich

Constructed of red brick and tile the houses have Voyseyian touches: steeply-pitched roofs sometimes coming down to door level; roughcast for the upper floors; coloured glass hearts and heart-shaped cutouts in the woodwork.

This house on Unthank Road shows the now-familiar heart-shaped cutouts on an asymmetrical porch.

Below, the house on Grove Road is a good example of how Arts & Crafts design became part of the everyday vocabulary of the local building trade. A neighbour said that his grandfather (“Youngs the Builder”) had built the house for his own family (presumably after the First World war).

Grove Road, Norwich

Handcrafted details include this decorative rainwater hopper

Sources

- Davey, Peter (1995). Arts and Crafts Architecture. Phaidon Press, Oxford.

- Anscombe, Isabelle (1991). Arts and Crafts Style. Phaidon Press, Oxford.

- Girouard, Mark (1990). Sweetness and Light: The Queen Anne Movement 1860-1900. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

- Hitchmough, Wendy (1995). CFA Voysey. Phaidon Press, Oxford.

- Blakesley, Rosalind P. (2006). The Arts and Crafts Movement. Phaeton Press, Oxford.

- Betjeman, John (1974). A Pictorial History of English Architecture. Penguin Books.

- Aslet, Clive (2011). The Arts & Crafts Country House. Arum Press, London.

- Tinniswood, Adrian (1999). The Arts and Crafts House. Mitchell Beasley, London.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus and Wilson, Bill. (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Thanks to David Bussey for background on the Eaton Road houses

I am enjoying these very interesting posts -thank you very much!

LikeLike

Thank you Lynne. Do you live in an Arts and Crafts house?

LikeLike

eye opener always a surprise and a delight thank you reggie

LikeLike

Thank you Alan.

LikeLike

Used to live on Kingsley Road and there is a lot more arts and crafts influence than just Tower House ( relatively modern name for it which was put there when it was refurbished about 15 years ago). Lovely circular sweetness and light windows in some of the houses plus art nouveau signage for Ludham Terrace. Enjoyed every minute living in the street!

LikeLike

By coincidence I went down Kingsley Road yesterday with my Arts and Crafts goggles on. That Ludham Terrace plaque is a joy, some lovely stained glass windows and terrific art nouveau tiles in the porches. Wonderful street.

LikeLike

Thank you for the most interesting articles! I love Arts and Crafts and am a descendant also of the Unthanks of Intwood Hall (though they are no longer there as of two or three years ago!). I live in Sydney in a 1920s California bungalow (Frank Lloyd Wright style). We’re having a lot of rain at the moment and it’s hard to keep the water out with the low pitched roof style. Makes me want a Lutyens roof with hand detailed red water hoppers and downpipes as in your photos.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Pamela. It’s interesting that Frank Lloyd Wright’s style managed to travel to Australia but not Lutyens. I did visit The Rocks many years ago and vaguely recall gingerbread Victoriana – did I miss Arts and Crafts?

LikeLike

A minor correction: I think you’ll find that Bedford Park is in Chiswick, not Ealing. I lived there until I was in y late 20s and used to drink in The Tabard. Enjoyed the article very much, by the way.

LikeLike

Pleased you enjoyed the article Adrian. Wikipedia says this of Beford Park: “Bedford Park is a suburban development in west London, England. It forms a conservation area that is mostly within the London Borough of Ealing, with a small part to the east within the London Borough of Hounslow.” But I bow to your local knowledge and have edited the text – thank you. Reggie

LikeLike

Thanks Reggie. I am aware that both ‘towns’ that Bedford Park straddles (Chiswick and Acton) have become parts of larger boroughs (Hounslow and Ealing, respectively). The Tabard is certainly in the Chiswick part so, technically, in Hounslow – just around the corner from Turnham Green tube station. Happy memories!

LikeLike

Love the “hearts of oak” chair.

LikeLike

Found it as an un-upholstered frame >30 years ago.

LikeLike

Great!

LikeLike

Pingback: Clocks | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Fantastic information! We are in an arts and crafts home in Norwich and have found some extremely helpful info here. Thank you!

LikeLike

So pleased you found that useful. I’d be intrigued to know what Arts & Crafts material you’ve found.

LikeLike