Tags

Edward Boardman, George Skipper, Norwich architecture, Norwich shoe industry, Norwich textile industry, Norwich University of the Arts, Norwich weaving

Who, at this Victorian horse market outside Norwich Castle, would have predicted that motor vehicles would displace horses from the city’s streets or that a shopping mall with space for over 1000 cars would be excavated where they once stood? This post is about once-vibrant buildings, such as stables, corn halls, weaving sheds and leather boot and shoe manufactories, that outlived their original purpose and had to be reinvented in order to survive.

Norwich horse market on site of former cattle market ca 1900. (c) Norfolk County Council

It is still possible to catch glimpses of life in the horse-drawn era.The words above this arch (shoeing, forge, livery, stable) in Orford Yard off Red Lion Street are a reminder of John Pollock’s veterinary surgery and livery stables. The date on the building’s Dutch gable gives the date of this Edward Boardman building as 1902. Boardman turns out to be a major figure in this post. The yard now accommodates Loose’s Cookshop and Chez Denis cafe and brasserie. Until 1998 the owner of Chez Denis had a previous business here, Cafe des Amis, the name of which can just be made out above the central arch in the photograph below.

The yard now accommodates Loose’s Cookshop and Chez Denis cafe and brasserie. Until 1998 the owner of Chez Denis had a previous business here, Cafe des Amis, the name of which can just be made out above the central arch in the photograph below.

![Red Lion St Orford Yard former stables [7536] 1998-03-10.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/red-lion-st-orford-yard-former-stables-7536-1998-03-10.jpg?w=529)

Former stables 1998, Orford Yard (c) georgeplunkett.co.uk

Above the gate, the last vestige of ‘Norwich Cooperative Industrial Society Limited’?

While the grander C19th public buildings tended to adhere to the binary choice between Classical or (particularly in the north of England) Gothic styles, the popularity of Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace of the 1851 Great Exhibition introduced a further option. Cast-iron was cheap and strong and, being able to support large expanses of glass on thin glazing bars, opened up new possibilities in which brick and stone were no longer the major players. In 1863, Holmes and Sons – who manufactured and sold agricultural machinery – built this showroom on Rose Lane. Now it is known as Crystal House and home to Warings furniture store.

The elegant facade of Crystal House (1863) – a great favourite of mine.

Haldinstein’s began making shoes in the early C19th and up until the early 1960s their Boot and Shoe Manufactory occupied seven blocks of buildings between Queen Street and Princes Street [1, 1a]. In the 1930s the firm went into partnership with the Swiss shoe company Bally but by the time shoe production stopped in 1999 only Bally remained [1]. The building at 2-4 Queen Street was renamed Seebohm House and now contains several businesses. The factory is dated ‘1872’ on the rain heads and, like Edward Boardman’s Colegate shoe factory of the same period (1876, see further below), is distinctly ‘modern’ and quite unlike Gothic Revival buildings of that period. However, the building does not appear to have been listed as one of Boardman’s despite his offices being only a few yards further down Queen Street in Old Bank of England Court.

The last remnant of the Haldinstein and Bally factory at 2-4 Queen Street

While the upper floors appear to look forward to C20th modernism – rejecting Neo-Gothic and Classical motifs – the appearance of the Gothic arch at the entrance is confusing and backward looking. The door grille, on the other hand, appears to anticipate the Art Deco period.

Clarification lies in the Norfolk Record Office whose files reveal that Boardman did design the Haldinstein building. His original plan shows that the doorway shared the same shallow (and decidedly non-Gothic) arch as the ground and first floor windows. The files also contain other plans by the Boardman practice, dated June 18th 1946, for “Proposed Alteration to Ground Floor”. These relate to a reorganisation of rooms but since this was the year that George Haldinstein sold his 51% share to Bally [1] it strongly suggests that the Gothic entrance was a post-war addition as was the ground floor’s patterned stucco .

Boardman’s plan for Haldinstein’s Queen Street factory, with Philip Haldinstein’s signature over the sixpenny stamp. Note the original door and its surround. (c) Norfolk Record Office BR35/2/23/10/1-43

In 1870, Foster’s Elementary Education Act decreed that towns would build Board Schools in which the teaching of religion was to be strictly regulated [3]. Funded by the local rates these were amongst the first public institutions to be open to both sexes. Thousands of such schools were built throughout the country. For Norwich’s own Board School in Duke Street, JH Brown designed a Higher Grade School that was opened in 1888. It was built by J Youngs and Sons (now a part of the RG Carter Group).

The Norwich Board School in Duke Street with the city’s coat of arms to the left, surmounting “Literature, Science and Art”.

Probably following London’s influential board schools the Duke Street school was built in the contemporary and progressive Queen Anne Revival style (see previous post). The school therefore has the Flemish, high-gabled silhouette with small-paned upper lights and tall casement windows typical of many of this country’s schools [3]. Recently, the building was extensively refurbished by the Norwich University of the Arts – not a major leap from its original purpose but a reflection of current trends in higher education.

Counterbalancing the image of the Victorians’ high moral purpose is the former skating rink in Bethel Street, where fun could be had by gaslight. Built as a roller-skating rink in 1876 it was then used for ten years (1882-1892) by the Salvation Army as their Citadel (see previous blog). The Citadel was entered from St Giles Street via the iron gates adjacent to the Army’s present building that was once Mortimer’s Hotel. I remember the skating rink towards the end of its 100 year occupancy by Lacey and Lincoln, builders’ merchants, before it was refurbished by the present owners in the 1980s. Now, Country and Eastern (below) is a spectacular eastern bazaar that – reflecting the owners’ interest in oriental culture – also contains a small museum of South Asian arts and crafts.

This factory-like building in St George’s Street was constructed in 1914 as premises for Guntons builders’ and plumbers’ merchants. At one time it was owned by Gunton and Havers – the latter being a relative of the actor Nigel Havers. Now the Gunton Building is another addition to the Norwich’s expanding University of the Arts.

The Gunton & Havers building in St Georges Street, Norwich 25th March 1967 (c) Archant/EDP Library

St Giles House (41-45 St Giles Street) – one of George Skipper’s big, Baroque and slightly overblown buildings – should dominate the street but it is set parallel to the road and difficult for the passerby to see face-on. It was built in 1904-6 for the Norwich and London Accident Insurance Association just after the opening of another of Skipper’s projects, Surrey House, for rivals Norwich Union: in fact, it has been described as “the Norwich Union in miniature” [4]. Its first rebirth was as a telephone exchange and is sometimes referred to as Telephone House. George Plunkett described it as “Municipal offices until 1938. Education and Treasurer’s departments.” Now it is a luxury hotel, St Giles House.

In 1770-5, the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital was built just outside St Stephen’s Gate by the architect William Ivory. However, the facade of the old hospital that we see today was the result of Edward Boardman’s makeover a century later. His pedimented Dutch gables and rather municipal clock tower do make it look like a town hall [4]. In 2001 a new hospital was built in the suburb of Colney and the old hospital was converted to apartments.

Another building designed by Boardman architects (father EB and son ETB) was for the Norwich Electric Light Company. In 1892 they converted the old Duke’s Palace Ironworks to a site where coal-fired boilers generated electricity that, by 1913, lit over 1750 street lamps around the city. Only 13 years later, superseded by the power station at Thorpe, the over-worked Duke Street site was converted to offices [5]. Now the offices are used by car-sharing company Liftshare.

The offices of the electricity works are dated 1913. Norwich City’s coat of arms is above the door.

![Duke St 4 Electricity works floodlit [1633] 1937-05-13.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/duke-st-4-electricity-works-floodlit-1633-1937-05-131.jpg?w=529)

Decorations on the floodlit electricity works celebrating the coronation of George VI (1937) (c) George Plunkett

Boardman House, interior. 2016.

In the latter part of the C19th Edward Boardman spearheaded Norwich’s expansion, from church rooms to factories – the very diversity of his projects underlining “his aesthetic flexibility”[6]. Howlett and White’s shoe factory (later the Norvic Shoe Co Ltd) became the largest in Britain and between 1876 and 1909 Boardman & Son designed various additions for the expanding enterprise [1]. By the 1930s Norvic occupied virtually all of the land from the river to Colegate and from Duke Street to St George’s Street. But in 1981 the business was in receivership after being asset-stripped of its shops after a takeover in the 1970s [1]. Now the former factory contains offices, apartments, The Last Winebar (a punning reference to its previous incarnation) and, since 2014, The Jane Austen Free School.

Part of Howlett & White’s ‘Norvic’ shoe factory. Edward Boardman designed right of the tower in 1876 and left in 1895.

In the face of competition from mills in the north of England, the mayor Samuel Bignold (son of the founder of Norwich Union) tried to bolster Norwich’s textile trade by establishing the Norwich Yarn Company. The company’s plaque – dated 1839 – can just be seen below the dome of St James’ Mill, built on the site of a C13th Carmelite monastery.

Ian Nairn of The Observer, who could be fierce in his architectural reviews, loved this building and called it “the noblest of all English Industrial Revolution Mills” [4]. Its engine-powered looms were not, however, sufficient to avert the threat to Norwich weaving. St James’ Mill was subsequently used by the chocolate manufacturers Caley’s and, until a few years ago, as Jarrold’s Printing Works. Currently, the mill houses private offices. Visit the John Jarrold Printing Museum,which is situated in a riverside building behind St James Mill.

As a county town Norwich benefitted considerably from the agricultural wealth of the surrounding countryside for which it was the trading centre. In 1882 this was recognised in the inauguration of the Norfolk and Norwich Agricultural Hall, designed for once by an architect other than Edward Boardman: JB Pearce. The opening ceremony was performed by the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) as Patron of the wonderfully named Norfolk and Norwich Fat Cattle Show Association [7]. It is not recorded what the cattlemen thought of Oscar Wilde’s lecture on “The House Beautiful”given at the Hall some two years later. The building now houses Anglia TV’s offices and studios.

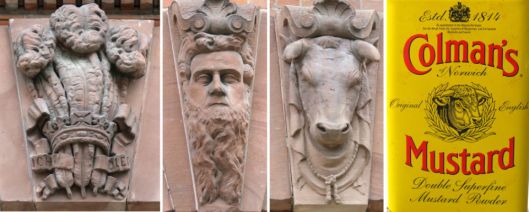

Pearce’s sombre public building is made of local red brick faced with a deep red and alien Cumberland sandstone [4]. Further decoration is provided by moulded Cosseyware (see previous post) from Guntons’ brickyard in nearby Costessey. The keystones above the ground floor doors and windows are decorated with heads or emblems. The Prince of Wales feathers refer not only to the prince himself but to the adjoining Prince of Wales road that connects Thorpe railway station with the former cattle market on Castle Hill. One of several heads is shown below; it is evidently a portrait but the identities of these agricultural worthies are no longer known. The reference to the bull’s head seems more straightforward but since JJ Colman was Vice-Chairman of the Agricultural Hall Company might this also allude to what had been Colman’s trademark since 1855? [8].

Sources

- Holmes, Frances and Holmes, Michael (2013). The Story of the Norwich Boot and Shoe Trade. Pub: Norwich Heritage Projects http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk Ref 1a: Burgess, Edward and Wilfred (1904). Men Who Have Made Norwich.

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/Industrial%20Architecture/Mountergate%20Coop%20shoe%20factory%20wall%20[7530]%201998-03-01.jpg

- Girouard, Marc (1984). Sweetness and Light: “Queen Anne” Movement, 1860-1900. Yale University Press.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus and Wilson, Bill (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1. Yale University Press.

- http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?MNF61834-Duke’s-Palace-Ironworks-and-Norwich-Electric-Lighting-Company&Index=53786&RecordCount=56542&SessionID=071f84aa-3266-4621-85cc-d97a40c30c46

- http://hbsmrgateway2.esdm.co.uk/norfolk/DataFiles/Docs/AssocDoc6824.pdf

- http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/industrial-innovation/agricultural-hall.htm

- http://www.mustardshopnorwich.co.uk/history-of-colmans-pgid15.html

Thanks. For permission to reproduce images I thank Jonathan Plunkett from the Plunkett archive; to Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk and to Siofra Connor of the Archant/EDP Library. I am also grateful to Frances Holmes, Philip Tolley and Diana Smith for their assistance.

Loved the photos and enjoyed the descriptions.

LikeLike

Thank you Lynne.

LikeLike

I enjoyed this – thanks.

Do you have any information about the wall paintings in Thornes? I think they are on the top floor.

LikeLike

I haven’t seen the Thorn’s wall paintings for a long time. I seem to remember that the building was once a dancing academy and the paintings were related to that. I phoned Thorns who told me that they are now on display, behind Perspex, on the first floor.

LikeLike

Thank you for following this up. I had heard that the building was once a hotel and that the room with the wall paintings was a function room but a dancing academy somehow sounds more appropriate. Great to hear that the wall is now on view. There’s a lot of ‘hidden’ or little known art in Norwich. For example, the 1960s panels on the old NatWest building sort of behind Cinema City. I can look on a map and be more specific if you are interested.

LikeLike

Dear Reggie

A very interesting article but please note that the John Jarrold Printing Museum is no longer in the undercroft but in a building behind St James Mill by the river.

LikeLike

Thank you Caroline – I’ve amended the post.

LikeLike

Interesting article as always…

LikeLike

I appreciate the comment, John

LikeLike

Dear Reggie, Thank you for the entry on pre-loved buildings. I look forward to reading it. Heide

>

LikeLike

I presume that amazing gallery and central staircase in Boardman House are original and designed by Boardman – not created as part of the refurbishment by the School of Architecture. Just beautiful! Interesting blog too, thank you, Deidre

LikeLike

Hi Deidre, I quote from the blurb by Hudson Architecture: “The main intervention in the atrium is a simple steel stair with a water jet-cut balustrade that picks up on existing 19th-century cast iron detailing and copies it in spirit, but not in direct application.” I agree that it’s an amazing addition that keeps to the spirit of Boardman’s original.

LikeLike

Surely the Coronation decorations on the Corporations Electricity works were for George V1. Interesting stuff as always

LikeLike

Thanks Don – corrected. The Plunkett photo was taken one day after King George VI (the Queen’s father) was crowned.

LikeLike

Pingback: Entertainment Victorian style | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Public art, private meanings | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Reggie through the underpass | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The Norwich Way of Death | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Philip Haldinstein and family of Thorpe Lodge Norwich – Cemetery Scribes blog.