Tags

angels in tights, Barton Turf, Booton church, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, James Minns, Knapton church, Norfolk churches, Norwich buildings, Norwich stained glass, Ranworth church, roof angels, Stained Glass, Stained glass angels

Angels aren’t as common as they used to be. Five hundred years ago, before the Reformation, church was where most people would see artistic representations. The subject matter was strictly religious with angels playing important parts. Angels were ubiquitous and could be seen painted on rood screens, or as wooden roof angels, on wall paintings, painted glass and carved in stone. The way that angels were represented in these religious contexts may, however, have borrowed something from less strictly religious mystery plays.

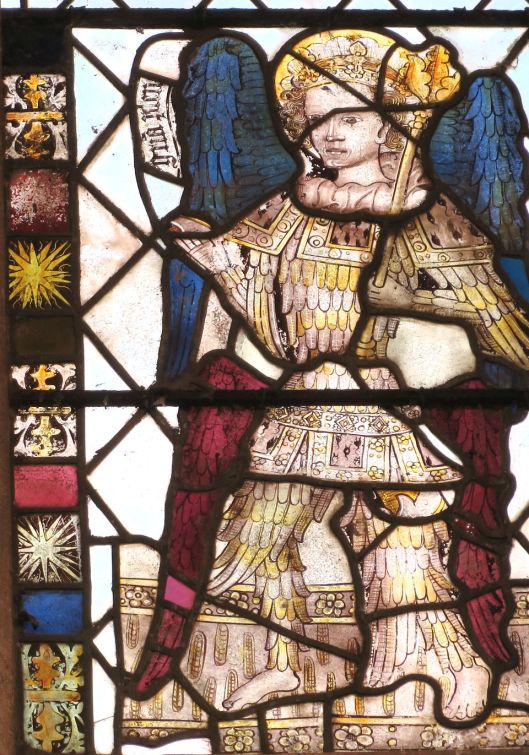

Archangel Gabriel wears a feather suit. C15th Norwich School glass, from St Peter’s Ringland.

In medieval mystery plays the angels would wear – in addition to wings – feathers that covered the body, ending neatly at neck and ankle. These costumes are variously described as ‘feather tights'[1] or feather-covered ‘pyjama suits’[2]. The roof angel below is covered with only few ‘feathers’ but this probably reflects the case that such body suits may have been covered with scale-like flaps of cloth or leather to represent feathers [1]. The feather suits worn by actors would have provided a model for the depiction of angels in church art, and vice versa.

Roof angel, St Agnes Cawston, Norfolk, adorned in relatively few large flaps painted as feathers. The Cawston angels are unique in standing upright on the hammer beams. Charles Rennie Mackintosh was fascinated by them (below).

In the early C13th, Pope Innocent III became so concerned about the growing popularity of clergy in these mystery plays that he banned them from appearing. The dramas were taken over by town guilds who courted popularity by dispensing with Latin and adding comic scenes [3]. Such performances were known to have taken place at York, Coventry and Norwich. From Norwich, one play survived: this was performed by the Grocer’s Guild and named Paradyse [3] or The Fall of Adam and Eve [4]. The text of the Norwich Stonemasons’ play, ‘Cain and Abel’ is lost [4]. The Norwich guilds are likely to have mounted their parts of the cycle in a pageant, which involved elaborate ‘pageant wagons’ [2], staged on the early summer feast of Corpus Christi [5]. This C19th engraving of the Coventry mystery pageant gives an idea of what such events looked like.

Coventry Mystery Pageant, engraved by David Gee (1793-1872). Source: Beinecke Library

There were nine orders of angels, ranked in order of importance [6]. Chief were the seraphim, with three pairs of wings (often depicted in red): one pair for shielding their eyes from God, one pair for flying and the third pair for covering their feet in respect. However, some say the latter were for covering their genitals, representing base instincts, and this is how they can appear in medieval images.

Six-winged angel at St Peter, Ketteringham, Norfolk. Norwich School painted glass late C15th

Cherubim had four wings, usually depicted in blue. Then, after Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Powers and Principalities we come to the more familiar Archangels who transmitted messages from God as Gabriel is doing in the first image above. Last were Angels – intermediaries between heaven and earth. Clarence was James Stewart’s guardian angel in “It’s a Wonderful Life”.

Clarence Odbody (Angel Second Class). From “It’s a Wonderful Life” RKO 1946

Some of the most beautiful medieval images of feathered angels in the country can be seen in Norfolk’s rood screens. Two stunning examples are at Ranworth and Barton Turf. Below, one of the Archangels, the “debonair and fantastical” [7] Michael, slays a many-headed dragon. The dragon probably represents Satan, who – according to Milton in Paradise Lost – was wounded by Michael in personal combat [6A].

Archangel St Michael from the church of St Helen, Ranworth, Norfolk. (C15th).

While most of the 12 screen panels in Ranworth represent saints, the equally beautiful rood screen at Barton Turf offers a rare depiction of The Angel Hierarchy. The painting can be dated to the late C15th based on the detailing on the armour [7].

Cherubim (left) have gold feathers, two pairs of wings and are typically covered with eyes. To the right is one of the Principalities. At St Michael and All Angels, Barton Turf, Norfolk

Left, Archangel Raphael – the leader of the Powers (usually depicted in their armour) – with a chained demon beneath his foot. The face on the devil’s belly denotes base appetites. Right, one of the Virtues.

Left: one of the Thrones holding scales, presumably for weighing souls. (This Throne has six wings normally used to depict Seraphim [6]). Right: an Archangel in late C15th plate armour. Note the fashionable late C15th turban.

The Dominion (left) and Seraphim (right) were probably defaced because of their papist tiara and incense-containing censer, respectively.

Curiously, the feathered angels swinging censers in the spandrels of the west doorway at Salle [8]– less than 20 miles from Barton Turf – were untouched by the iconoclasts.

St Peter and St Paul, Salle, Norfolk

Angels were commonly depicted playing musical instruments. A favourite is this beautiful painting of an angel playing a harp at All Saints East Barsham. The glass was probably painted in the latter part of the C15th by the Norwich workshop of John Wighton [9] (see my first blog post on Norfolk’s Stained Glass Angels).

The harpist wears a fashionable turban. The ‘ears of barley’ at the bottom are typical of the Norwich School’s way of depicting wood grain.

Another harp player at St Peter and St Paul, Salle.

At St Mary’s North Tuddenham this angel plays the lute…

… and at St Peter Hungate, Norwich – bagpipes

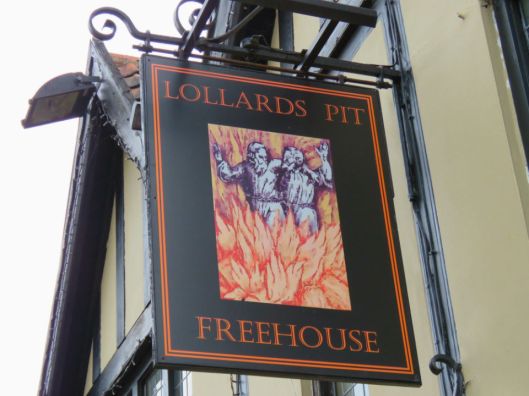

One of the glories of East Anglia is the large number of angel roofs, 84% of which are found in this region [13]. David Rimmer has examined two explanations for this. The first focuses on the Lollard heresy. (The name derives from their mumbling at prayer [from Middle Dutch lollaert = mutter]). Lollards were followers of John Wycliffe who – over a hundred years before the Protestant Reformation – objected to the pomp, imagery and idolatry of the Catholic Church. Their first martyr, who was burnt at the stake in London 1401, had been priest at St Margaret’s King’s Lynn. Lynn’s church of St Nicholas was the site of East Anglia’s first angel roof (1405-9) [13] suggesting that the large number of angels in East Anglia could be a counterblast to the Lollardism that was rife throughout this region. In Norwich, men and women were burnt in Lollards Pit, a chalk pit once used for digging the foundations of the cathedral.

Lollards’ Pit pub near Bishop Bridge, Norwich

Another hypothesis involves the Royal Carpenter Hugh Herland who had created the first angel roof at Westminster Hall in 1398. Herland and his craftsmen came to make the new harbour at Great Yarmouth and it is argued that his influence spread throughout the region (although the first datable angel roof was in Kings Lynn [then Bishops Lynn] rather than Great Yarmouth).

Norwich has five* angel roofs: St Mary Coslany, St Michael at Plea, St Peter Hungate, St Giles and St Peter Mancroft [13]. (*A reader later informed me that St Swithins, which houses Norwich Arts Centre on St Benedicts Street, also has an angel roof hidden in the black-painted interior). St Peter Mancroft Norwich has a particularly fine mid C15th angel roof, said by Michael Rimmer to be “virtuoso medieval carpentry” [13]. The Perpendicular fan vaulting in wood masks hammerbeams whose free ends are capped by angels.

St Peter Mancroft, Norwich

Cawston, north of Norwich, has one of the finest angel roofs. As well as the demi-angels with spread wings, forming a frieze around the wall plate, man-size angels stand vertically at the ends of each hammer beam as if ready to dive.

Single hammer beam roof at St Agnes Cawston

Thrust from the heavy roof tends to splay the walls outwards. Opposite walls can be held together by tie braces that span the width of the church but in hammerbeam roofs, the force is deflected downwards onto the jutting hammerbeams beams that only project partway into the volume. Cawston has a single row of these hammerbeams. Below, Knapton has double hammerbeams, allowing an ‘amazing’ span of 70 feet [7]. Double-deckered angels at the ends of these beams, together with two rows on the wall plate, result in a total of 138 angels.

The roof was added to C14th Knapton church in 1503. This probably dates the earliest angels [7] although some clearly derive from later restorations – the lower rank from the 1930s [10].

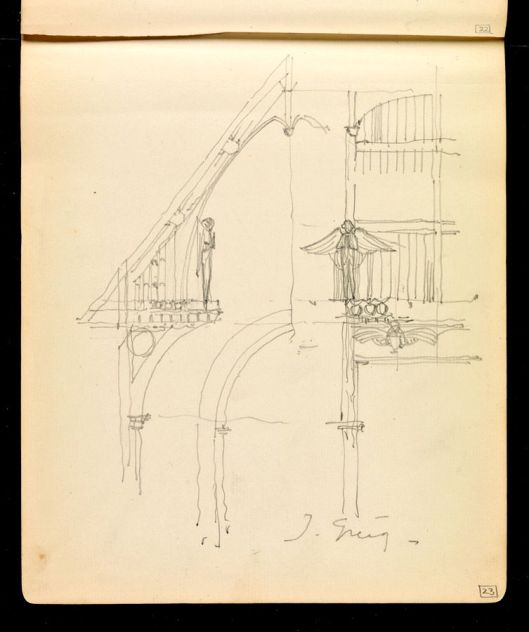

One of the lower Knapton angels, dating from the restoration of the 1930s Charles Rennie Mackintosh is associated with East Anglia by the pencil and watercolour drawings he made when he and wife Margaret stayed in Walberswick, Suffolk, in 1914. But he had previously visited Knapton, Norfolk, in 1896/7.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Knapton roof angels. Creative Commons. Source: Glasgow School of Art Archives and Collections 1897 [Ref11]

Pencil drawing. Roof truss St Agnes Cawston 1896? (c) The Hunterian Museum Art Gallery, University of Glasgow 2016.[ Ref 14]

Most agree that the stained glass and roof angels made up for other misjudgements. The local master carpenter James Minns carved this hovering roof angel at Booton [13].

James Minns is also credited with designing the bull’s head emblem for Colman’s mustard [13].

Left to the end: how Jeremiah James Colman made his money [15]

** STOP PRESS. WHO WAS JAMES MINNS? **

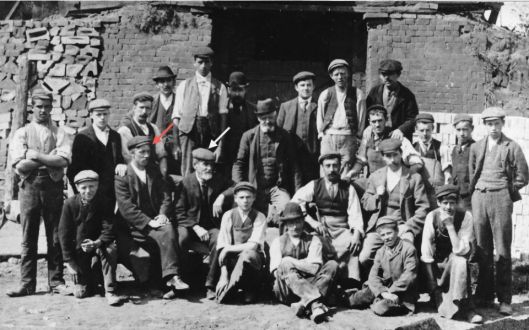

Just as I was finishing this article, Costessey resident Peter Mann responded to a previous blog article on Gunton’s brickworks by naming all the workers (below) at the Costessey brickyard. Excitingly, he identified the arrowed figure as James Minns with John Minns seated on his right. Both were labelled as “Carvers of Norwich”, consistent with census returns giving their occupations as ‘carver’ (or, once for James, ‘sculptor’). The entry for Minns [16] on the Mapping of Sculpture website gives his full name as James Benjamin Shingles Minns (ca 1828-1904). James was sufficiently confident of his skill to submit (successfully) a carved wooden panel of ‘A Happy Family’ to the 1897 Summer Exhibition of the Royal Academy; he had also carved the mantelpiece and panelling for Thomas Jeckyll’s commission for the Old Library at Carrow Abbey (1860-1) [17]. The presence of this highly skilled sculptor and his son at the Costessey Brickyard strongly suggests that they carved the moulds for the ornate ‘fancy’ bricks and panels for which Guntons were locally renowned. From his independent status as ‘Carver’ it seems possible that “James Minns of Heigham” [17] might have been freelance rather than a full-time employee, especially since his address was ca. five miles away from the Costessey Brickyard.

Employees of the Guntons Brickyard Costessey. James Minns is arrowed (white) with his son John, arrowed red. Pre-1904. (c) Ernest Gage Collection at Costessey Town Council

Norwich is a small city and its many lines of history are interwoven. A previous blog focused on the Boileau Memorial Fountain once sited at the junction of Newmarket and Ipswich Roads. James Minns collaborated again with architect Thomas Jeckyll by carving this coat of arms in the tympanum of the fountain [17].

“Minns of Heigham” [17] carved this plaque for the Boileau Fountain formerly at the Newmarket/Ipswich Road junction. (C) Norfolk Library and Information Service: Picture Norfolk

Church of St Michael Booton. A rather stern St Michael sheaths his sword, with a bemused Jabberwockian dragon at his feet. Attributed to sculptor James Minns.

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feather_tights

- http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O7802/panel-norwich-school/

- http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Mystery_play

- http://gildencraft.blogspot.co.uk/2016/04/the-norwich-stonemasons-play-by-gail.html

- http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/medieval/mystery_plays.php

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_angelology Ref 6A: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_(archangel)#Art_and_literature

- Mortlock, D.P. and Roberts, C.V. (1981). The Popular Guide to Norfolk Churches; I. North-East Norfolk. Pub: Acorn Editions, Fakenham.

- http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/salle/salle.htm

- King, David. (2004). Glass Painting. In, Medieval Norwich eds C. Rawcliffe and R.Wilson. Pub, Hambledon and London. pp121-136.

- http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/knapton/knapton.htm

- http://www.gsaarchives.net/archon/?p=collections/findingaid&id=459&rootcontentid=10386

- Jenkins, Simon(2000). England’s Thousand Best Churches. Pub: Penguin.

- http://www.angelroofs.com/images-2

- http://www.huntsearch.gla.ac.uk/cgi-bin/foxweb/huntsearch_Mackintosh/DetailedResults.fwx?SearchTerm=53014/11&reqMethod=Link

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeremiah_James_Colman

- http://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/person.php?id=ann_1283258555

- Soros, Susan Weber and Arbuthnott, Catherine (2003). Thomas Jeckyll: Architect and Designer, 1827-1881. Pub: BGC, Yale.

- http://www.racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp?action=getsurvey&id=1065

Thanks to Peter Mann for identifying James Minns; Brian Gage for giving permission to reproduce an image from the Ernest Gage Collection at Costessey Town Council; Paul Cooper for providing the new photograph of the Guntons workers; Jocelyn Grant of the Glasgow School of Art for assistance with Mackintosh’s (K)Napton angels; Michael Rimmer of angelroofs.com for his help with the Norwich angels; and Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk.

Four brilliant sites

- For Norfolk churches visit : http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk

- For roof angels see: http://www.angelroofs.com

- For an interactive search of Norfolk’s stained glass visit: http://www.norfolkstainedglass.co.uk/Norfolk/home.shtm

- And for photographs of old Norfolk visit: https://norfolk.spydus.co.uk

Really really interesting. Inspired to go angel-spotting now.

LikeLike

Great place to start would be the Norwich angel roofs.

LikeLike

Hi Reggie. do you know when Angels first got their wings? Was it an art device to differentiate between them and mortals? Alan

LikeLike

There are several references in the bible stating that some orders of angels had wings. Isaiah Ch6 v2: “Above it stood the seraphims: each one had six wings; with twain he covered his face, and with twain he covered his feet, and with twain he did fly.” Ezekiel 10:1-22 has numerous references to cherubim having wings but perhaps not all did since angels were sometimes confused for men. Note that guardian angel Clarence in ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ didn’t have wings.

LikeLike

I want my feather tights now …

Best wishes from Andover, NH.

LikeLike

They’re in the post …

LikeLike

Thank you for your very informative essay on angels. There are certainly marvelous examples in Norfolk churches. We like Ranworth and Barton Turf especially. Thank you for all your hard work. Alastair.

LikeLike

Yes, it’s sometimes hard for Norfolkians to appreciate just how fortunate we are in having access to so many medieval treasures.

LikeLike

Wonderful again – thank you! I’m just back from Bury St,Edmunds where I took a picture of the wonderful angels in the roof of St. Mary’s. The church is often closed when I go, so it was a treat to have access. With love, Heather

LikeLike

I must go to Bury again soon – beautiful town (city?)

LikeLike

Your mention of the medieval Mystery Plays brought back happy memories of seeing a performance back in the late 70s or early 80s with Brian Glover & Karl Johnson in it. At the time I didn’t notice the Angels ….. wish now I had taken more note!! The performance was terrific, though!

LikeLike

I remember Brian Glover as the gym master in Ken Loach’s Kes. Great actor.

LikeLike

Pingback: The flamboyant Mr Skipper | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The angel’s bonnet | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Norfolk Rood Screens | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH