Ken Skipper of the Cork Brick Gallery, Bungay, recently lent me this small book on historical events in Norwich. It starts with the castle being built by King Uffa the First in 575AD and ends on July 30 1900 with the Electric Tram Company running their “first Cars for the Public”. All the early events are big ticket items, official record entries like, “981 The City was utterly destroyed by the Danes”. Compared to this the C19th entries seem inevitably mundane yet they are fascinating for providing insight into mass entertainment in the Victorian age. As we shall see, this is closely linked with developments in transport.

“1825. September 7. Col. John Harvey, High Sheriff, ascended in a Balloon from Richmond Hill Gardens.” Before the age of mass transport, pleasure gardens at the periphery of the crowded medieval city centre were important sources of entertainment. London had its famous C18th Ranelagh and Vauxhall Gardens [1]: Norwich had its versions too. Norwich’s Ranelagh Gardens were just outside the city walls between what is now St Stephen’s Road and Sainsbury’s supermarket. The ornamental gardens contained The Adelphi Theatre, a skittle alley and the Pantheon arena where firework displays would help depict famous British victories [2, 3].

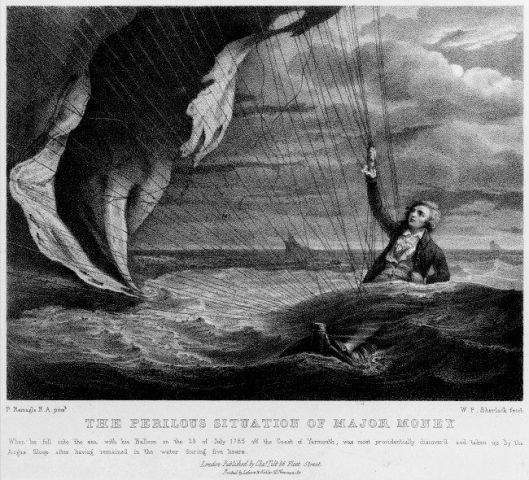

The High Sheriff’s flight from another pleasure gardens in Bracondale was evidently uneventful but in July 1785, only two years after the Mongolfier brothers’ first balloon flight, The Ranelagh Gardens had been witness to a more dramatic event when Colonel Money of the East Norfolk Regiment of Foot ascended in an ‘aerostatic globe’ [4, 5]. Unfortunately, an ‘improper current’ took him out to sea, off Yarmouth and Lowestoft. In his words:

I ascended from this place with a balloon, and was drove out to sea, not being able to let myself down from the valve being too small. After blowing about for near two hours I dropped in the sea. My situation, you may easily conceive, was very unpleasant… [6].

A Byronic Colonel Money struggling for his life off Yarmouth. Courtesy Picture Norfolk, Norfolk County Council

“1826. Humbug on Mousehold. Signor Carlo Gram Villecrop’s ‘leap'”. [A humbug: a trick, a deception] Mousehold Heath – the high ground overlooking the city – was another venue capable of accommodating large crowds. According to a circulated bill, Signor Villecrop the Swiss Mountain Flyer promised to appear there on the 28th of August and with his 50 foot Tyrolese pole would perform:

the most astonishing gymnastic flights never before witnessed in this country… (and) … will frequently jump forty and fifty yards at a time[4].

Not Signor Villecrop. ghost-in-the-library.tumblr.com

He would run up St James’ Hill with the pole between his teeth, lie on his back and balance the pole on his nose and on certain parts of his body, walk up and down the hill on his head balancing the pole on his foot. Twenty thousand people came to see him but it was, of course, a hoax.

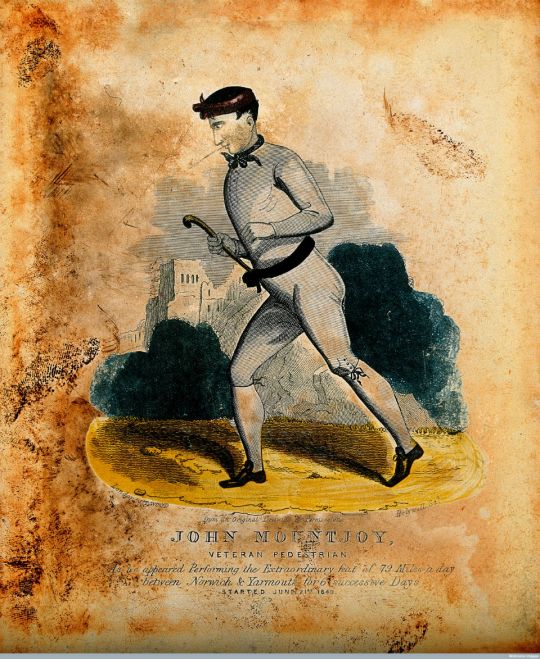

“1840. June 21. Mount Joy walked from Norwich to Yarmouth and back twice a day for six consecutive days”. John Mountjoy was referred to as ‘a veteran pedestrian’ – that is, a speed walker – and in the summer of 1840 he performed a series of remarkable feats [5].

John Mountjoy, Veteran Pedestrian. Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London

He started his twice-daily walk from the Shirehall Tavern, Norwich, to Symonds’ Gardens, Yarmouth and when, six days later, he crossed Foundry Bridge for the last time a ‘tremendous crowd bore the toll collectors before them and made a free passage’. Previously, on the 16th of June at The Ranelagh Gardens he had taken up with his mouth, without touching the ground with his knees, 100 eggs a yard apart and dropped them into a bucket of water without breaking them. Warming to his theme, on the 13th July he ran a mile, walked a mile backwards, ran a wheelbarrow half a mile, trundled a hoop a mile, hopped 200 yards, picked up with his mouth 40 hazelnuts etc etc …

“1847. Douro and Peto were chaired, at which stones were thrown at Douro.” This economically-worded entry glosses over what others have called the Norwich election riots of 1847: an example of When Crowds Go Wrong. Samuel Morton Peto was an eminent Victorian responsible for building The Reform Club, Nelson’s Column, The Houses of Parliament, London’s brick sewers etc. [7]. Peto was a major railway contractor and was said to have been the largest employer of labour in the world [8]. He built railways around the globe but is remembered locally for building the lines that connected Yarmouth and Lowestoft to Norwich and London. The speed and capacity of trains finished the coaching trade to London [9] but allowed large numbers of Norwich citizens to spend leisure time at the growing seaside resorts, like Cromer, Yarmouth and Lowestoft. Glance up next time you visit Norwich Rail Station.

On the concourse of Norwich Station, “Sir Samuel Morton Peto 1809-1889. Baptist Contractor Politician & Philanthropist”

In the election The Marquis of Douro (The Duke of Wellington’s son) and Peto won two of the available seats, leaving the other candidate – the Non-Conformist Serjeant Parry – well behind. Two hundred of Peto’s navvies from the Eastern Counties Railway paraded merrily through the city until they met Parry’s disgruntled supporters. Stones were thrown. The outnumbered navvies became barricaded in The Castle Inn, windows were broken and the police had to use horse buses to transport the workers to a special train waiting at the station. Peto paid £70 towards the damage. Whether or not this constituted a riot depended very much on the newspaper that reported the affair [7].

“1858. Huffman’s Humbug on the Old Cricket Ground”. Now, you would have thought that those who had been bamboozled by Villecrop’s humbug in 1826 would have warned the next generation when Mr JW Hoffman came to town. But Hoffman had previously been to Norwich as manager of his ‘Organophonic Band’ (a full orchestra with just the human voice) so it did appear as if he could put on a show [5].

Courtesy Terry Drayton

On this occasion Hoffman had widely advertised a medieval pageant on the Old Cricket Grounds, presumably at Lakenham.

The Cricket Ground, Lakenham, Norwich. (c) Dereham Times

The big difference between this and the previous humbug was that the railway had in the meantime come to Norwich – the Yarmouth line in 1844 and London via Brandon in 1845. And The Ranelagh Gardens were now occupied by Victoria Station. Train companies ran excursions, crowds thronged the streets; once again the city was immobilised and business was suspended. With so much anticipation the pageant, which consisted of 30-40 people on foot following a man on a horse, was an anti-climax and was met with boos and hisses. The ‘Old English Sports’ that followed were also a failure, ending with general fighting amongst the blackguards at the ground [5]. But the long arm of the law soon caught up with Hoffman for in September 1858 The London Gazette mentioned that John William Hoffman, Professor of Music and Elocution, Exhibitor of Ventriloquism, and Caterer for Public Amusement in General, and of 16 previous addresses, was being sued in Shrewsbury County Court [10].

“1868. Aug 13. Mr Maris ascended in a Balloon from the Market-place, which was lost at Sheringham.” Balloon flights continue to be mentioned in The Record of Local Events throughout the C19th. We do know that some balloons were filled with coal gas at the City Gas Works in Bishop Bridge then led to the launch site. It isn’t known how the balloon was filled on this occasion but hundreds of people waited all day in the market place to see the ascent. At about six o’clock, Mr Maris the fruiterer ascended with Mr Simmons the aeronaut. After two minutes they had already risen to 10,000 feet from where Mr Maris was able to point out towns as far apart as Harwich and King’s Lynn. However, the noise below of threshing machines and barking dogs very soon gave way to the sound of the sea and they had to make an emergency descent. Fortunately, they jumped out over land but the balloon, now lighter, re-ascended and was lost in the sea at Sheringham [5].

Norwich balloon ascent, late C19. (c) Norfolk County Council. Picture Norfolk

“1849. Jenny Lind sang.” Jenny Lind, ‘The Swedish Nightingale’, was one of the most popular sopranos of the early-mid C19th and she was more deeply embedded into Norwich life than this brief note could suggest [11].

She first came to sing in St Andrew’s Hall in 1847 …

… two years later, at the age of 29, she announced her retirement from opera although she still appeared in the concert hall and even toured with showman TP Barnum in the States. She was highly philanthropic and the money she raised from concerts in 1849 and 1854 [11] funded the city’s Infirmary for Sick Children in Pottergate. Her name lives on in the Jenny Lind Children’s Hospital at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital. Another reminder is provided by the memorial gate in the Jenny Lind Park off Vauxhall Street, left isolated by the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital’s move to Colney. I remember my children saying they were off to play in the Jenny Lind.

“1895. June 1. The Jenny Lind Steamboat burned”. Steam power would shape the nineteenth century. The little record book mentions the first steamboat on the Yare in 1813 but this later reference is to a serious fire that occurred at Foundry Bridge. Launched in 1879 the Jenny Lind would run daily excursions from the quayside next to Thorpe Station and travel the few miles down to Bramerton Woods where there was an inn and a seven-acre pleasure garden [12]. The Jenny Lind would also steam down to Brundall Gardens, known as “The Switzerland of Norfolk”because of the 120 acres of wooded slopes surrounding a lake [13].

Jenny Lind steamboat at Brundall Gardens (c) broadlandmemories.co.uk

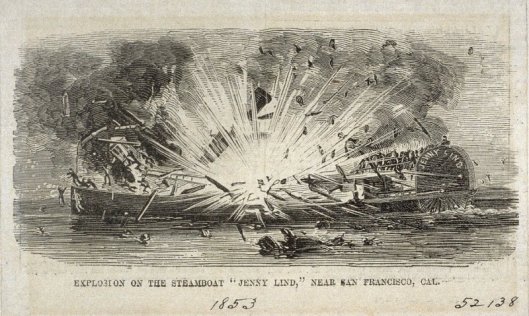

The ship apparently survived but another steamboat named ‘Jenny Lind’was not so fortunate. In 1853, the US steamboat Jenny Lind – a ferry between Alviso and San Francisco– exploded just as dinner was called [14]. Superheated steam flooded the dining room, killing 34 passengers.

Explosion of the American ‘Jenny Lind’. (c) Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

“June 23 1879 Norwich Omnibus Company started.” Increased mechanisation saw workers leave the countryside and find jobs in the city’s industries; by the end of the C19th Norwich’s population had tripled to ca 100,000. Horse-drawn omnibuses carried citizens around the city for 20 years but the company stopped business on December 17 1899 [16].

A horse-drawn Norwich omnibus. Photo 1977 (c) Joe Mason [15]

“July 30. 1900. The Electric Tram Company ran their first cars for the Public.” By mid-century, steam engines were carrying people long distances over land and water but within towns and cities horse-power still reigned. But, never an efficient means of mass transport, omnibuses were withdrawn in 1899 and superseded by the horseless carriages of the Norwich Electric Tramways Company [16]. Power was provided by the Norwich Electric Light Company that, from 1892, generated electricity at the old Duke’s Palace Ironworks off Duke Street [see 17].

There were seven routes. The tram above, at the junctions of Newmarket and Ipswich Roads would have been on the Green route to Cavalry Barracks [16]. If Norwich’s industrial workers wanted to get away from the grime they could, in the summer, take the extension up the hill to Mousehold Heath, scene of Signor Villecrop’s humbug three quarters of a century earlier.

The Norwich Society helps people enjoy and appreciate the history and character of Norwich. Visit: www.thenorwichsociety.org.uk

Thanks: to Ken Skipper, Joe Mason, Terry Drayton, broadlandmemories.co.uk, Picture Norfolk (norfolkspydus.co.uk) and Mary Parker for their assistance.

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ranelagh_Gardens

- John Riddington Young (1975). The Inns and Taverns of Old Norwich. Pub: Wensum Books.

- http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/at-leisure-in-norwich/norwichs-pleasure-gardens.htm

- Carol Twinch (2012). The Norwich Book of Days. Pub: The History Press.

- Charles Mackie (2010). Norfolk Annals, a Chronological Record of Remarkable Events in the Nineteenth Century. http://archive.org/stream/norfolkannalsach34439gut/34439.txt

- Scots Magazine June 1785

- Terry Coleman (1965). The Railway Navvies. Pub: Hutchinson.

- http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Samuel_Morton_Peto

- http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/industrial-innovation/norwich-railway-station.htm

- https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/22186/page/4313/data.pdf

- https://norfolkwomeninhistory.com/1800-1850/jenny-lind/

- http://www.broadlandmemories.co.uk/pre1900gallerypage2.html

- http://www.brundallvillagehistory.org.uk/gardens.htm

- http://www.mercurynews.com/2013/04/08/herhold-ceremony-set-to-remember-1853-jenny-lind-steamboat-disaster/

- https://joemasonspage.wordpress.com/2012/01/22/colmans-mustard-omnibus/

- http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/social-innovation/swish-rattle-and-clang.htm

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/07/28/norwichs-pre-loved-buildings/

Very nteresting account of the entertainment of the time. You might like to see what Sir John Boileau wrote in his diary about Jenny Lind after attending her concerts.

Sir John Peter Boileau of Ketteringham’s diary (NRO MS 21470)

22nd September 1847 at Norwich

At half past six to concert of Mad’elle Jenny Lind and the St Andrew’s Hall as full as possible & very beautiful. She sung very finely. Her organ most powerful and much cultivated and great execution & occasional sweet notes beyond any I ever heard but on the whole there is a want of any great effect upon one produced by her either of excitement or tender emotion like Catalini, Pasta, Malibran ….. Her shake is very beautiful and liquid – gurgling – and her sustained notes very clear and just. Her Swedish melody curious a very spirited Ranz des Vaches (an Alpine herdsman’s song) – but rather barbarian wild and coarse. Her appearance and manner are very pleasing and without a pretence at good looks. She is an interesting person.

23rd September 1847 at Norwich

Dined early and to concert where Jenny Lind sang better still than last night ……..

20th January 1849 (Sir John returning to Norwich from Audley End by train)

Jenny Lind in the next body (compartment) to us going down to her two concerts at Norwich, annoyed by people staring in at her.

23rd January 1849 at Norwich

At (Bishop’s) Palace…. Jenny Lind came in and introduced to her. She is taller than she looks on the stage and has a good humoured smiling broad featured face without colour – and easy nice manners – speaks bad English & is graceful in her movements. I could not judge of her mind beyond the intelligent look of her face.

7th February 1849 at Norwich

..then with Lord Colborne to call on Chas Wodehouse about Mr Allden, met Edward W there and had to subscribe £1.0.0. for Jenny Lind’s dresses etc

LikeLike

Thank you Mary for this fascinating contemporary insight into Jenny Lind. It’s good to hear from someone who actually heard her sing.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed this post very much. Thank-you.

LikeLike

Thank you Clare. You can still spot the old electric tram poles along Ipswich Road

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really!! I must open my eyes I think. I was there today (my daughter attends City College) and actually found somewhere to park the car for free for 2 hours! I’ll have a look for them in the morning 🙂

LikeLike

Correction: look along Newmarket Road

LikeLike

These posts give such huge pleasure and food for exploration and thought – thank you!

LikeLike

There is a photo on ‘picture norfolk’ of the interior of the circus rotunda that was in the Ranelagh pleasure gardens……later Victoria Station. It was used for the latter as the booking office, as in the photo which I guess is c1910. I gather that when it was still a circus Pablo Fanque ( William Darby d1871) performed there. He was a black man born in Norwich who went onto being immortalised by John Lennon’s Being For The Benefit of Mr Kite!”:

‘For the benefit of Mr. Kite

There will be a show tonight on trampoline

The Hendersons will all be there

Late of Pablo Fanques’ fair, what a scene…’

LikeLike

Great connection Sally. Just looked up Picture Norfolk to see the rotunda that once stood in Ranelagh Gardens. And what a wonderful connection to Pablo Fanque.

LikeLike

Another really interesting article. I remember playing at the Jenny Lind playground in the early ’70s when it was very different to today.

The Jenny Lind Playground gate was originally located in Pottergate. Jeremiah James Colman had built a new and enlarged hospital for children on the corner of Colman and Unthank Roads at the end of the nineteenth century, transferring all but the outpatients department. After the death of his youngest son, Alan, Jeremiah decided to provide a ‘children’s pleasure ground’ in his memory using some of the now redundant land in Pottergate. It was officially opened on 5 June 1902 with the ornate entrance. By 1970 the area had become depopulated and a decision was made to redevelop the Pottergate site for housing, with a new playground being provided off Union Street near the maternity block of the Norfolk and Norwich hospital. The gateway was transferred in 1972.

LikeLiked by 1 person

David, It’s great to hear that you have first-hand experience of the Jenny Lind playground. You might be interested a photo I used in a previous post (https://wp.me/p71GjT-2OY). It’s from Picture Norfolk, showing the gateway in Pottergate (1902-1972) as you probably remember it.

LikeLike

Pingback: Pleasure Gardens | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH