Tags

Carl Linnaeus, James Edward Smith, John Innes Collection, Linnean Society, Pleasance Smith, Unitarianism

*… the natural world.

This is the story of Norwich-born James Edward Smith and his involvement with the way we describe and classify the living world … but beneath this lies an important sub-text about the role of dissent in the advance of knowledge.

Father and son: James Smith and James Edward Smith (c) The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, and Wikimedia Commons

James Edward Smith (1759-1828) was son of James Smith (1727-1795), a wealthy Norwich wool merchant. This was at a time when Norwich could still claim to be one of England’s major cities, before mechanisation shifted power to the northern towns. James Edward was a shy, delicate child who was taught at home, at 37 Gentleman’s Way. His mother’s love of plants may have stimulated his precocious love of botany [1].

James Edward Smith age 3 years 8 months, by Mrs Dawson Turner after a drawing by T Worlidge

His continuing botanical education was to be shaped, however, by the family’s religion – Unitarianism. At that time the two English universities, Oxford and Cambridge, only offered botanical studies as part of a medical course since physicians were required to prepare drugs from medicinal plants. But such studies were closed to non-conformists like Smith since only members of the Church of England were allowed to receive a degree. Against this rising tide of dissent (and by 1829 one in seven of Norwich adults were dissenters [2]) those who could afford it had to be educated elsewhere, at dissenting colleges or universities in Scotland and the Continent. So James Edward Smith went to Edinburgh and, rather prophetically, started his studies on the day that the famous Swedish naturalist, Carl Linnaeus, died [1] .

Old College, Edinburgh (c) ed.ac.uk

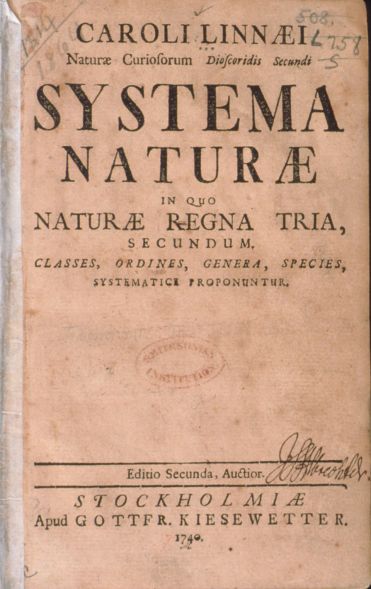

The Enlightenment of the C17th and C18th saw free-thinkers looking beyond the rigid views of the established church and embarking on a more tolerant examination of ideas through scientific enquiry and philosophical reasoning. The C18th was a period of great exploration, not only mapping the world but collecting as many examples of its flora and fauna as possible. After the gathering phase came the sifting stage in which naturalists tried to understand the underlying plan. At Edinburgh, Smith was a student of Dr John Hope, who was one of the first to teach Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) system for classifying plants and animals. Decades later, Charles Darwin (1809-1882), a fellow Unitarian, was also to study medicine at Edinburgh where he was exposed to debate about creation and whether species were God-given (i.e., fixed) or changeable.

(c) Smithsonian Libraries

The Linnaean system of classification placed plants into groups based on the number and arrangement of their reproductive organs.

The sexual basis of this system was not without controversy. Johann Siegesbeck called it ‘loathsome harlotry’ [3] and Linnaeus’ revenge was to give the name siegesbeckia to a small, useless weed. (Later, Smith was cautioned not to copy Linnaeus’ foul use of “scrotiforme and genitalia”[11]).

The original system based solely on the arrangement of sexual organs was imperfect but two key parts survive in the improved version used today. The first was Linnaeus’ method of placing organisms into hierarchical groups based on shared similarities, from kingdom down through class, order, genus, species (other groups were added later). The second survival was his binomial system in which the two names – genus and species –were sufficient to identify a plant or animal. Before this, plants were referred to by long, imprecise Latin descriptions whereas the binomial system could tie down a specific plant. For example, there are many roses in the genus Rosa but addition of the specific or species name canina distinguishes the dog-rose (Rosa canina) from the red rose (Rosa rubra). Hierarchical classification and the relationship between species can be seen as an important precursor to Darwin whose Tree of Life added an extra dimension by showing that species were not fixed at the time of the Creation but mutable, evolving over time.

Linnaeus died in 1778; his son Carl inherited his father’s collections and when he died only five years later they were offered to the President of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820), who had befriended Smith in London. The Empress of Russia had tried to buy the collections as had the King of Sweden who is said to have sent a ship to intercept them.

Engraving by Robert John Thornton of the apocryphal pursuit of the Linnean Collection by a Swedish frigate. (c) The Linnean Society of London

Banks could not afford the 1000 guineas himself but persuaded Smith to borrow the money from his wealthy father and so James Edward Smith became possessor of Linnaeus’ 3000 books and 26 cases of plants and insects. Smith was rewarded by being elected Fellow of the Royal Society within two years: three years later he founded the Linnean Society of London, remaining President for the rest of his life [1, 4].

But metropolitan life did not agree with Smith so he returned to Norwich for nine months each year. Ill health is often quoted as a reason but he was known to be fed up with the “envy and backbiting” of London life [11]). In 1796 he married a Lowestoft woman, the letter writer and literary editor, Pleasance Reeve. Lady Reeve was painted as a gypsy by fashionable portraitist John Opie when she was 24: she was to live another 79 years.

Left, Pleasance Smith by John Opie (Wikimedia Commons). Right, by Hannah Sarah Brightwen after Opie (c) National Trust Images, Felbrigg, Norfolk

Two unavoidable discursions:

- The wife of portraitist John Opie – Amelia Opie the novelist and abolitionist – lived at the corner of Castle Meadow, Norwich and is commemorated by a statue in nearby Opie Street [5].

- Pleasance, who was childless, was evidently close to her niece Lorena Liddell (née Reeve) who gave her daughter the middle name ‘Pleasance’ after her aunt. This child, Alice Pleasance Liddell, was of course the inspiration for Alice in Wonderland. [6].

Alice Pleasance Liddell aged 20 by Margaret Julia Cameron (Wikimedia Commons)

When Smith married Pleasance, her father gave them the tall Georgian town house, 29 Surrey Street, Norwich, as a wedding present. The garden that once contained Smith’s beloved plants was sold in 1939 to the Eastern Counties Bus Co [7]; No 29 itself was bomb damaged during WWII while the adjoining part of the terrace was worse hit and replaced somewhat unsympathetically after the war.

29 Surrey Street, Norwich (centre). Two houses to the right were replaced after the war.

The row of houses had been designed by local architect Thomas Ivory (1709-1779), who contributed much to Georgian Norwich [6]. Not only did he design The Assembly House and the terrace in Surrey Street but he built the elegant Octagon Chapel in Colegate. Smith was deacon there when in 1820 the ownership of the chapel transferred from the Presbyterians to the Unitarians.

For as long as he lived in Norwich the house in Surrey Street, and not the Linnean Society, was the private museum in which Smith housed the Linnean collection. This included Linnaeus’ three herbarium cabinets arranged so that ca. 14000 specimens – plants dried on sheets of paper – could be easily referenced [1]. Attracted by Linnaeus’ own type specimens “Norwich (became) the centre of the biological and natural history study of the world” [8]. In 1938, two of the cabinets returned to Sweden but the Linnean Society retained one plus all contents.

One of Linnaeus’ original herbarium cabinets (c) Linnean Society of London [9]

Smith maintained a prodigious output. Between 1790 and 1823 he published 36 volumes of English Botany [10]. The series, which was issued by subscription, contained over 2,500 hand-coloured plates by illustrator James Sowerby: indeed, the work was sometimes called Sowerby’s Botany because Smith – unsure about being associated with a popular illustrated work in English – left his name off the first edition [11].

Lady’s-slipper orchid by James Sowerby from JE Smith’s English Flora. Courtesy John Innes Foundation Collection of Rare Botanical Books

Smith also wrote Flora Brittanica (1800-1804) and The English Flora (1824-1828). At the time of his death Smith had also edited eight and half of the 12 volumes of John Sibthorp’s survey of Greek flowers, Flora Graeca [12] – a beautiful publication, each with 100 plates illustrated by Ferdinand Bauer (the final volume by Sowerby having 66 plates).

Sibthorp’s Flora Graeca compiled by James Edward Smith. Courtesy John Innes Foundation Collection of Rare Botanical Books

At one time, Smith instructed Queen Charlotte, the wife of King George III, and her daughters; he taught the elements of Botany and Zoology but this relationship was cut short after he criticised the French court and mentioned the republican Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The dissenting mind once again confronted the establishment when Smith tried unsuccessfully to become Professor of Botany at Cambridge University – his non-conformity, support for the abolition of slavery and of Greek independence, did not help his cause [1].

Perhaps surprisingly, Smith did not bequeath his collections to the society he had founded and of which he had been President for life. Instead, he left instructions that they were to be sold as one lot to a public or corporate body, causing The Linnean Society to purchase the very reason for their existence for the vast amount of £3150 – a sum that took them over 40 years to pay off [1].

There is a memorial plaque to Sir James Edward Smith on the north side of the nave in St Peter Mancroft, Norwich, but his body was interred in his wife’s family vault in the churchyard at St Margaret’s Lowestoft.

©2017 Reggie Unthank

Thanks to archivist Sarah Wilmot for providing access the rare books in the John Innes Historical Collections. Visit http://collections.jic.ac.uk/. It is an amazing resource and Sarah encourages visits and invitations to talk (sarah.wilmot@jic.ac.uk).

Sources

- https://www.linnean.org/library-and-archives/library-collections-of-j-e-smith/biography

- Rawcliffe, C., Wilson, R. and Clark, C. (2004). Norwich since 1550. Pub: A&C Black.

- http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/linnaeus.html

- Gage, A.T. (1938). A History of the Linnean Society of London. Pub: Linnean Society London.

- http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/whos-who/amelia-opie.htm

- Do read Joe Mason’s fascinating blog on this house, where his family had lived. https://joemasonspage.wordpress.com/2012/05/22/the-story-of-a-house-1/

- http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/whos-who/thomas-ivory.htm

- http://www.nnns.org.uk/sites/nnns.org.uk/files/imce/user11/publications/natterjack/NJ108.pdf Quote from Tony Irwin page 20.

- https://ca1-tls.edcdn.com/listing/_c960xauto/Herbarium-Cabinet.jpg?mtime=20160705144628

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Botany

- White, P. (1999). The purchase of knowledge: James Edward Smith and the Linnean Collections. Endeavour 23: 126-129.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flora_Graeca

The Norwich Society helps people enjoy and appreciate the history and character of Norwich. Visit: www.thenorwichsociety.org.uk

Reggie, a fascinating summary – it will ensure that I will take more notice of an otherwise (to me) relatively unnoticed memorial at St Peter Mancroft and I was particularly taken by the link to Alice Liddell. Mark Little

LikeLike

Hello Mark, The interconnectedness of things never ceases to amaze me – I enjoyed stumbling across that particular link. Reggie

LikeLike

Great read – thank you

LikeLike

Thank you Rose. Reggie

LikeLike

Thank you, I enjoyed reading your blog.

LikeLike

Thank you Lynne. Reggie

LikeLike

The interconnection between objects, persons, and things is an amazing subject and open to endless wonder and conjecture. Thanks Reggie

Thank YOU for the kind commentsTheo. Reggie

LikeLike

I so look forward to your posts Reggie! This one had me enthralled from start to finish – thank-you.

LikeLike

Thank you for the kind words Clare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure.

LikeLike

Dear Reggie,

Thank you very much for your comments on the Smiths. I was particularly interested in the connection to Linnaeus. He was a very nasty man, though. – It is also sad to think that the bus station was once a nice garden.

Heide

>

LikeLike

Yes, Heide, you would have thought that the importance of Smith’s garden would have been recognised in the 1930s.

LikeLike

Another great, informative article. Thanks for all your efforts.

LikeLike

Thank you Nigel. Reggie

LikeLike

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #23 | Whewell's Ghost

These posts give me so much pleasure, especially in the cold dark days when it’s nicer to stay inside and amass ideas for future explorations… Thank you!

LikeLike

Yes, it takes an effort of will to foray out from Unthank Towers in this weather. Thank you Heather.

LikeLike

Pingback: Norwich: City of Trees | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The Norfolk Botanical Network | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Catherine Maude Nichols | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Georgian Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The Sons of Flora | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH