There is little now to suggest that Norwich had an industrial past but the parish of Coslany, around the River Wensum, was once home to iron works, shoe factories, an electricity generating works and a brewery – all providing employment after the slow decline of the city’s wool-weaving trade.

From the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, Barnard Bishop and Barnards’ Norfolk Iron Works was a major part of the industrial landscape of Norwich-over-the-water.

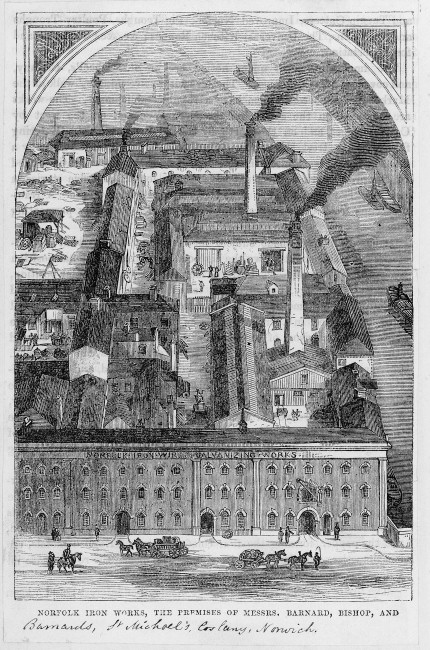

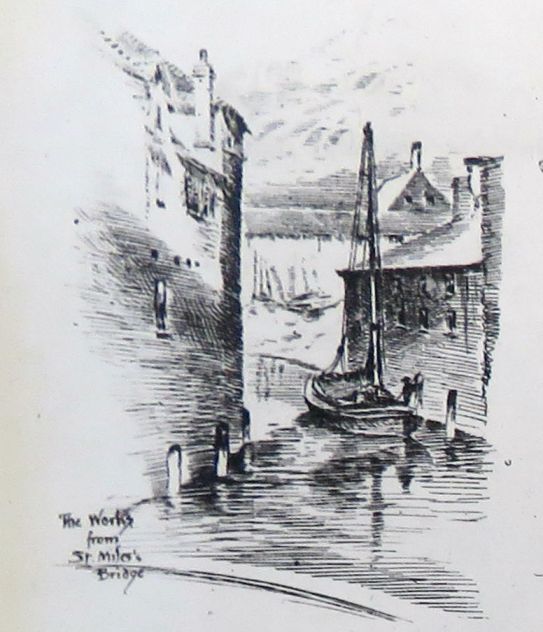

Barnard, Bishop and Barnards’ Norfolk Iron Works. Courtesy Picture Norfolk (www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk)

Ordnance Survey 1908. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland (maps.nls.uk/index.html)

The son of a farmer, Charles Barnard (1804-1871) started making domestic and agricultural ironwork in Pottergate in 1842 [1]. Having lived on the land, Barnard was aware of the damage that wild animals could wreak on crops and began to experiment on a machine for weaving wire netting. Initially the netting was made on the machine below but later it was produced by a powered loom. Netting was to be remain a core activity well into the C20.

Barnard’s loom for weaving wire netting at The Museum of Norwich

In 1846 Barnard went into partnership with John Bishop, then in 1859 Barnard’s sons Charles and Godfrey joined the business, becoming Barnard, Bishop and Barnards.

Barnard Bishop and Barnards’ ‘four Bs’ trade sign – the two smaller bees representing Charles Barnard’s sons. Courtesy of The Museum of Norwich

This ‘four Bs’ rebus marks the firm’s attachment to puns: their designer Thomas Jeckyll used his own two-butterfly signature from the time of his early collaborations with Barnard and Bishop. Jeckyll, incidentally, was a friend of Frederick Sandys who drew the portrait of Charles Barnard (unable to show): both inserted a rogue ‘y’ into their surname.

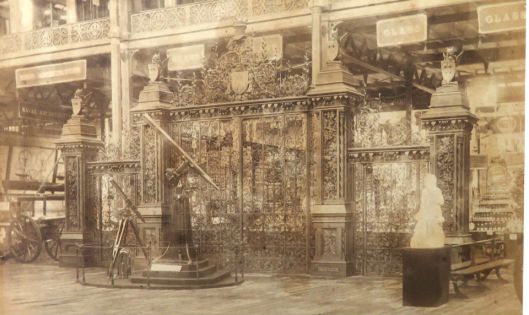

I have already written at length about Jeckyll [2-5] but it’s not possible to omit him entirely since it was his designs that brought Barnards national attention, elevating some pieces to high art. Two examples: first, the intricate wrought and cast-iron ‘Norwich’ gates that won the firm ecstatic praise at the 1862 International Exhibition;

The Norwich gates, given to the Prince and Princess of Wales in 1863 as a wedding present by the citizens of Norwich and Norfolk. Now at Sandringham House, Norfolk. Courtesy of The Museum of Norwich

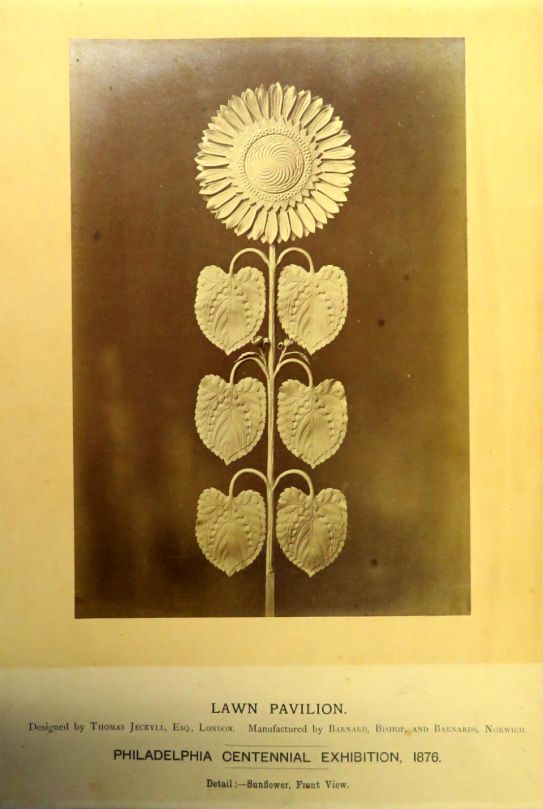

second, Jeckyll’s associations with a group of London artists – notably James Abbott McNeill Whistler – made him a key figure in the Anglo-Japanese Aesthetic Movement. Jeckyll used japonaise designs for Barnards’ fireplaces while his cast iron sunflower (to be seen on the gates of Heigham Park and Chapelfield Gardens) came to symbolise the Aesthetic Movement.

Courtesy of The Museum of Norwich

In 1871, Barnards moved their iron works to Calvert Street in the parish of St Michael-at-Coslany.

St Miles Works from the river. Courtesy The Museum of Norwich

The business contained a large foundry at one end while a new building housed the netting mill, for which steam was used to power the looms [1]. The factory was also known as St Michael’s Works; Miles is a diminutive of Michael and both are also applied to one of the city’s most beautiful churches, the elegant St Michael Coslany.

Barnard Bishop and Barnards St Miles Works 1951. The works had several tall chimneys but the one shown here may belong to Bullard’s Anchor Quay Brewery on the other side of the river. ©2017 RIBApix

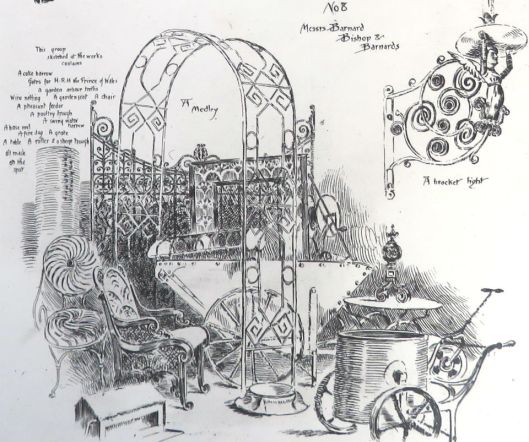

At the St Miles site the workforce of ca 400 produced an eclectic range of utilitarian objects. The drawing below lists: “a coke barrow, a garden arbour, trellis, wire netting, a garden seat, a chair, a pheasant feeder, a swing water barrow, a hose reel, a fire dog, a grate, a table, a roller & a sheep trough. ‘All made on the spot’“.

Courtesy of The Museum of Norwich

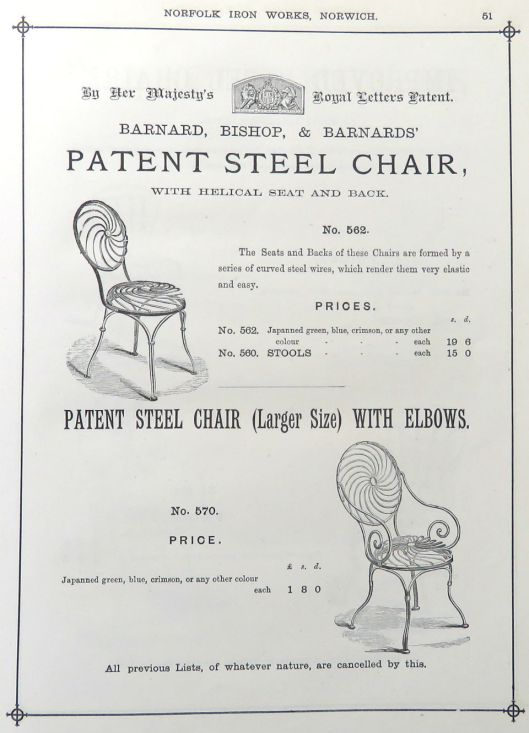

Still desirable. Garden chairs from Barnard Bishop and Barnards 1884 catalogue for their London showroom. Courtesy of The Museum of Norwich

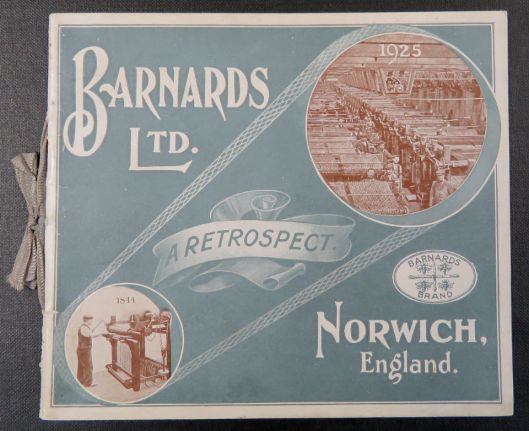

Barnards celebratory brochure 1844-1925. Courtesy of The Museum of Norwich

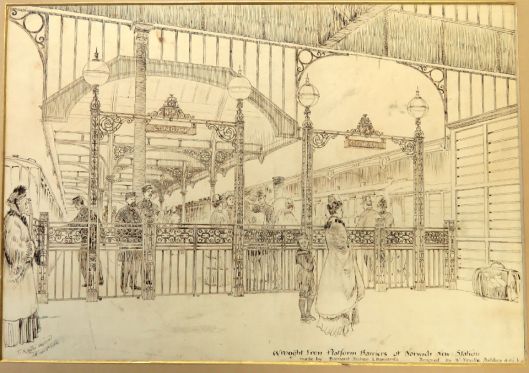

The railways arrived in Norwich in the mid-C19 and Barnards provided much of the metal work for at least two of the city’s three stations. These ornate barriers at Norwich Thorpe station were made by Barnards and were designed by W. Neville Ashbee, the company architect for the Great Eastern Railway.

The wrought iron platform barriers at Norwich Thorpe station. Courtesy of The Museum of Norwich.

The barriers have gone but the cast-iron canopy supports with the elegant spandrels can still be seen along the platforms.

The station forecourt is still enclosed by fine examples of Victorian ironwork.

Barnards also cast the columns and spandrels for Norwich City station. This station near the St Crispin’s roundabout was the terminus of the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway whose hub was at Melton Constable. It closed to passengers in 1959.

Norwich City station. Courtesy of The Museum of Norwich NWHCM 118.959.51

In 1882, a river bridge was built to provide access to the new City Station. St Crispin’s Bridge, which was manufactured by Barnards, became part of the ring road in 1970 taking traffic in clockwise direction. A new bridge built parallel to it takes traffic in the opposite direction.

Charles Barnard died in 1871 but the firm lived on as Barnards Limited (from 1907).

Mr and Mrs Charles Barnard in later life. Image courtesy of Norfolk Record Office via http://www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

The managing director James Bower played a direct part in the running of the company, rebuilding and re-designing the wire netting machines. In 1921 they purchased part of the old Mousehold Aerodrome where, in the Second World War, they manufactured gun shells and parts for the Hurricane fighter. This attracted the attention of the Luftwaffe who bombed the site in July 1942, killing two people [6].

The Norwich engineering firm, Boulton and Paul, made aircraft (including the Overstrand and Sidestrand) but who knew that Barnards helped make planes? Barnards also made buses …

Bus made by Barnards Ltd in Cathedral Close. Image courtesy of Norfolk Record Office via http://www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

… and at their factory in Salhouse Road they produced steam traction engines.

Image courtesy of Norfolk Record Office via http://www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

Barnards Ltd ceased trading in 1991. The Coslany site is now occupied by social housing – Barnards’ Yard.

Barnards’ Ironworks now Barnards’ Yard social housing

©2017 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- Williams, Nick (2013). Norwich, City of Industries (an excellent book on industrial Norwich).

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2015/12/26/two-bs-or-not-tw…s-thomas-jeckyll/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/04/15/thomas-jeckyll-the-boileau-family/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/01/06/jeckyll-and-the-sunflower-motif/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/11/10/jeckyll-and-the-japanese-wave/

- http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/industrial-innovation/barnards.htm

Thanks to Hannah Henderson of The Museum of Norwich for kindly showing me the Barnards collection, and I also thank David Holgate-Carruthers for his help. Do visit the Museum of Norwich, which has a section devoted to Barnards and Jeckyll and gives a fascinating glimpse into Norwich as it once was. I am grateful to Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk for allowing me to reproduce photographs. Clare manages (https://norfolk.spydus.co.uk/cgi-bin/spydus.exe/MSGTRN/PICNOR/HOME), which contains a searchable collection of 20,000 images of Norfolk life.

An interesting subject very well covered- I hope you will cover that at some future date you will also cover Laurence and Scott. Thanks Col.Unthank

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the tip on L&S, Theo. Unlike Barnards and Boulton & Paul they managed to survive.

LikeLike

I’m led to believe that the 3 impressive and unique ‘A-Frame bridges’ (of which only 2 survive at Hellesdon and Drayton) out of City on the old EMR (later M&GN) line were also made by Barnard, Bishop and Barnard, however they have nothing to identify their maker and I can’t find anything to confirm this.

LikeLike

So pleased to make contact with a blogger from Mile Cross. I have never seen these bridges mentioned in a list of Barnards’ work but that doesn’t mean much. I shall certainly look out for them whenever I look through the archives. Kind regards, Reggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating! I’ve learnt so much reading your posts. I was just at Heigham Park yesterday and saw those lovely gates again. Drew Pritchard was selling one of those sunflowers for £4500… Wow! Also very excited as we’re buying a house very near the park that has a Jeckyl fireplace complete with his butterfly emblem. It’s exactly the same as one in Norwich museum. It has the wrong surround though, a wooden victorian repro one with lots of detail, I guess a more simple one would have been there originally?

LikeLike

Thank you Susie. It’s great that the enlightened council have kept reproductions of the sunflowers at both parks – they really are an important part of Norwich history. I envy you buying a house with a Jeckyll fireplace and would love to have one myself. I’ll dig out some pictures of the kinds of surround they used. As you say, they are quite simple. Reggie.

LikeLike

Thank-you for another informative and fascinating post, Reggie. I have often wondered about the sunflowers at Chapelfield Gardens and now I know!

LikeLike

Hello Clare, Thank you for the kind comments. A better description of Jeckyll’s sunflowers is on https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/01/06/jeckyll-and-the-sunflower-motif/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic! Thank-you so much, Reggae.

LikeLike

These posts give me such pleasure. Sometimes there isn’t time to digest them when they first come, so I store them up carefully to enjoy later, like a dog with the juiciest of bones – thank you!

LikeLike

Hi Heather, Although this was one of my shorter posts it is still not a quick read. I’m pleased to think you may return to it.

LikeLike

hello all was very interesting to read up on the Barnard Bishop and Barnard foundry, I am a fireplace dealer and I have had a few Jeckyll fireplaces pass through my greasy mitts and I think the designs from him and the foundry are awe inspiring and works of art in their own right, I have recently come into possesion of a Barnards slow burning combustion fireplace which I believe is a one off, or prototype as I cannot find a picture or reference of it anywhere I have contacted Norwich Museum as I intend to donate it as it is, in my opinion, historically important and too nice to go to a private home! I can post a picture of it once it’s restored, its def designed by the famous Thomas Jeckyll. Cheers

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Peter, I would VERY much like to see a photograph of your fireplace; it sounds intriguing. Did you contact The Museum of Norwich (the old Bridewell), which is where the Barnards/Jeckyll collection is kept?

Interestingly, my daughter just moved into a house that has a superb Barnards fireplace – I’m very jealous.

Best, Reggie

LikeLike

quick question did bernards make umbrella stands? have a beautifull one with swallows and cranes on it, no makers mark, but arts and crafts in all its glory!

LikeLike

I think I recall Barnards making umbrella stands. They made a lot of domestic ware so it’s quite probable. So no butterflies in a roundel to show it was made by Barnards.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Bridges of Norwich 1: The blood red river | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Barnard Bishop and Barnard had a showroom on gentleman’s walk Now the Halifax bank I worked there when it was Hope Brothers shop gentleman Taylors there was a large castiron support right across the shop with bosses containing the four bees desigin., No sign of it now anyone know if it’s still there covered over or has it been removed?

LikeLike

Terry, Delighted to hear of a connection to Barnards’ showroom on Gentleman’s Walk. In a previous post (https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/11/10/jeckyll-and-the-japanese-wave/) I showed a photo of Hope Bros shop in which you worked. Then (1920s?) there were iron balconies beneath the five second-floor windows but they are gone as, I suspect, are any internal fittings.

LikeLike

Reggie. That’s a great picture of Hope Brothers shop very much as I remember it in the late 60s early 70s I expect most of the internal fittings have been removed. I remember a very heavy Safe set in the wall on the first floor, a swing-out gantry at the back to raise goods to the second floor. The first floor was open to the ground floor with balustrading round this had been filled in but the balustrade was still there. On the second floor, there was a lovely victorian blue and white porcelain toilet bowl and cistern Hope that has been recycled somewhere. Out the back was a well mostly filled in with an Iron winch. The building has a Large seller that extends out under the road.

LikeLike

Hello Terry, It would be good to have seen the building as it was. But it sounds as if the fittings were still more or less intact when you worked there. By the way, are you related to THE Ketts? Just finished Tim Holden’s fascinating book about the so-called rebellion. Reggie

LikeLike

Your readers may also like to know that the Norfolk Record Office has held, since 1990, the surviving archive of records from the firm of Barnard’s Ltd of Norwich, including several illustrated catalogues from the latter half of the 19th century onwards, early cash accounts, partner’s correspondence, director’s papers, and employee records, along with later advertising and publicity photographs, and Barnard family albums. These are all free to view at the NRO under our catalogue reference, BR 220. The list of the records is available online via the NRO’s website: http://nrocatalogue.norfolk.gov.uk/index.php/records-of-barnards-ltd-of-salhouse-road-norwich-ironfounders .

LikeLike

Thank you Tom. I look forward to visiting the NRO again when this becomes possible.

LikeLike