Tags

Anglia Square, Gildencroft, Lucams, Magdalen Street flyover, Norwich Strangers, Norwich Yards or Courts, psychogeography, St Augustine's Street Norwich

On the map it was meant to be a straight enough radial walk from a city gate into the city centre but I’m easily distracted. I got lost around Gildencroft where – as the psychogeographers among you will know – an historic area clings on among the after effects of postwar modernisation.

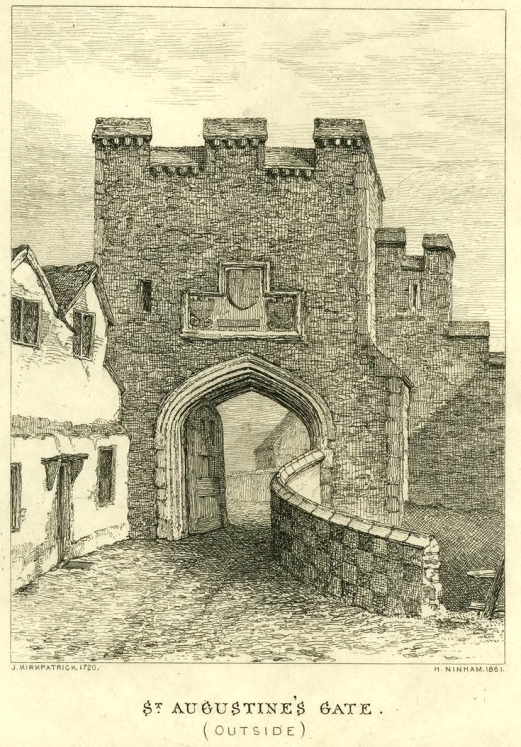

Henry Ninham’s 1861 engraving, based on John Kirkpatrick’s 1720 drawing. Norfolk Museums Service. NWHCM : 1953.31.FAP33

There was a time you were free to imagine yourself a nineteenth century flâneur like Baudelaire, strolling along the boulevards without a care [1]. But midcentury psychogeographers like Guy Debord, with their socio-political ideas about the effects of environment on the pedestrian’s psyche, put a stop to that, making a new wave of urban explorers more conscious about the impact of urban development [2]. In Psychogeography [3], Will Self wrote about walking to Manhattan from his house in south London (not over the watery bit, obvs) in order to regain “the Empty Quarters“: the hinterlands around airports.

Psychogeography ©Will Self (words) and Ralph Steadman (artist). Bloomsbury Publishing 2007

And in his ‘alternative cartography’ around the M25 London Orbital, Iain Sinclair famously wrote about walking through urban no-man’s land. Other twenty-first century urban walkers (the new psychogeographers) suggest taking a playful approach to the exploration of the built environment, employing a variety of tricks to nudge the pedestrian off the beaten path to make them more aware of the urban landscape. Rob Macfarlane recommends following the path drawn on a map by an upturned tumbler; others throw dice at each intersection or perform ‘ambulant signmaking’ by following a letter traced on a map; and one urban runner even used the GPS in his running shoe to geotrack the shape of his privy member on the map. Hmm. This may be why Lauren Elkin (“walking is mapping with your feet”) [4] writes about the need for female flâneuses to reclaim the streets. There’s a lot of hoo-ha around psychogeography but, at heart, it’s about the way that urban development affects our lives.

The Gildencroft area of St Augustine’s parish is over the A147 inner ring road. St Augustine’s Gate (lost in the C18) is marked very approximately with the blue bar. ©OpenStreetMapcontributors

I started my walk, not at the old city gate, but by taking a closer look at a building I’d glimpsed from my car. So at the outset I travelled contrariwise. This was on Starling Road, just off Magpie Road (red star), which runs parallel to the old city wall. The building is a relic of the once thriving Norwich shoe industry that, like much of the city’s trade, took place here in Norwich-over-the-water (Ultra Aquam). The concrete lettering on the parapet reads: The British United Shoe Machinery Co Ltd 1925 [5].

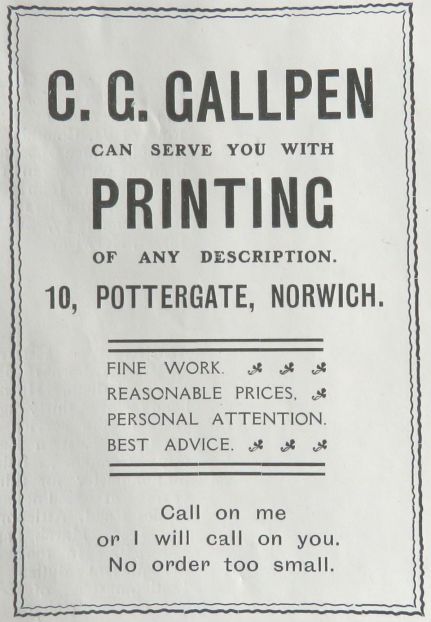

Once, this Leicester firm made equipment for the Norwich shoemakers but collapsed in 2000. Now the building is occupied by Gallpen who – in a nice example of nominative determinism – are printers (ink used to be made by adding iron salts to tannic acid extracted from oak galls). In a 1910 trade book the founder, Charles Gaunt Gallpen (b 1859), advertised himself as a printer with the unintentionally ominous slogan: “Call on me or I will call on you” [6].

From [6]

Crossing busy Magpie Road, I passed a segment of the city wall and part of a tower revealed by the demolition of Magpie Printers in 2013.

The medieval city wall would have continued beyond the houses to the right, passing across St Augustine’s Street to emerge on a tract of land between Bakers Road to the right and St Martin’s at Oak Wall Lane to the left.

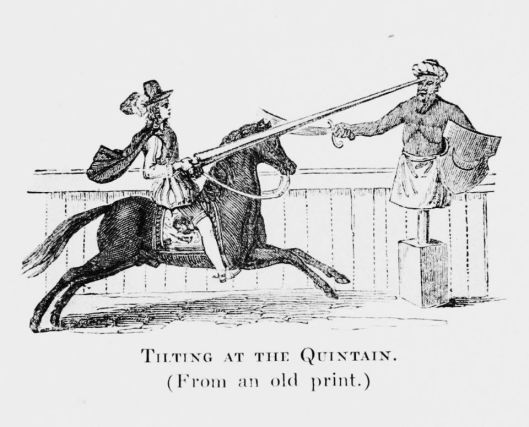

What we are looking at is the external ditch and on the inner side of the wall was a tract of land once known as the Jousting Acre [7]. Here, men-at-arms practiced jousting with lances and – as was compulsory in the medieval period – young men would have performed their archery practice with bows or crossbows. The antiquary Francis Blomefield mentions that King Edward III came to a tournament that local historian Stuart McLaren suggests is likely to have been held at this Jousting Acre [7].

In the 15th year of his reign, the King appointed a turnament to be held at Norwich … this exercise was much in use in ancient times, and is otherwise called jousting or tilting; the knights that used this martial sport were armed, and so encountered one another on horseback, with spears or lances, by which they made themselves fit for war, according to the manner of that age, which made use of such weapons … this turnament began in February 1340, and the King … was at Norwich on Wednesday February 14, being St. Valentine’s day. (Francis Blomefield 1806 [8])

Sussex Street is one of the most attractive streets in this part of the city, containing rows of Georgian terraced housing dated mainly to 1821-1824 [9].

14 & 16 Sussex Street (south side)

These were probably houses for the respectable working/lower middle class; Number 22 (below) is more genteel.

22 Sussex Street. Doorway with Greek Doric columns and segmental arch with fanlight

There is a similar doorcase on No 21 on the opposite side of the street. This house forms part of a terrace of three-storeyed houses. To the left can just be seen part of the 1971 conversion to flats by Edward Skipper and Associates. As we know, George Skipper [10] built the architectural fireworks of late Victorian Norwich and laid out much of the Golden Triangle in the early C20. The family name lives on in St Augustines.

Behind, and to the left, is the modern development, Quintain Mews – the name commemorating medieval jousting.

The quintain was a revolving target that would, when struck with lance or sword, swing around to sandbag the combatant.

Wikimedia Commons

On the opposite side of Sussex Street is the entry to 42 modern, split-level dwellings – The Lathes – owned by Broadland Housing Association. This development was built in 1976 by the architects Teather and Walls, described as ‘Associate for Edward Skipper and Associates” [11].

The word ‘lathes’ is dialect for a grain barn [7], commemorating the farm that once stood in this area. According to Blomefield [8] the farm belonged at various times to Sir John Paston, and two Shakespearean heroes: Sir John Fastolff of Caister (Falstaff is mentioned in five plays) and “brave Sir Thomas Erpingham” (Henry V) whose statue is above the Erpingham Gate of Norwich Cathedral. One suggestion is that Erpingham installed this pious statue to assert his religious orthodoxy at a time when the Lollards were asserting themselves [12]

Sir Thomas kneels in a niche above the Erpingham Gate

Historically and architecturally St Augustine’s is a fascinating street but the temptation to flit from one side of the road to the other is inhibited by the volume of traffic flowing out of the city. Still, this hasn’t put off the young artists who are adopting the street.

On the west side of the street a ghost sign was recently uncovered when No. 22 became Easton Pottery [13]. I can pick out ‘Easton’, ‘Florists’ and perhaps ‘Newsagents’. Trade directories show that from the 1930s to the 1960s a Miss E Easton ran a florist’s shop here. Before that she, and her father before her, ran a greengrocer’s. But the current owner, the potter Rachel Kurdynowska, found that T Easton traded here in 1873 as an earthenware dealer and it is in honour of this serendipitous connection that Rachel named her business.

Ghost sign for the Easton family businesses, now Easton Pottery #22 St Augustine’s Street

The oversized roof gables known locally as lucams are a prominent feature of the east side of the street. ‘Lucam’ may be a corruption of ‘lucarne’, a French word for skylight donated by immigrant ‘Strangers’ – C16-17 Dutch and French-speaking Walloons who could have used the term for the windows at which they reinvigorated the city’s weaving trade [14]. The owner of No 33 (left), who is just coming into view, told me that he had recently repaired his lucam.

Lucams at 33 and 31 St Augustine’s Street

Nunn’s Yard, a fine range of five upper gables on 23-25 St Augustine’s Street

The recently renovated numbers 23 and 25 announce themselves as ‘Nunn’s Yard’, which is actually further up the road between numbers 31 and 33. Instead, Nunn’s Yard Gallery is now the name of an enterprise whose two other contemporary exhibition spaces are doing much to enliven this street: Yallop’s and Thirteen A [15].

Yallop’s and Thirteen a.

The entry to Hinde’s Yard can be seen to the left of Thirteen A and the cast-iron signs for other yards are encountered along the street.

The influx of Strangers in the Elizabethan era created a demand for housing within the confines of the city walls; this was met by squeezing poorly-built, insanitary ‘yards’ or ‘courts’ into the courtyards of larger properties fronting the streets [16]. Before WWII there were 70 houses in Rose Yard. The only source of water for 50 of them was the public pump in St Augustine’s churchyard. An 1851 report mentions, “at the bottom is a large pool of nightsoil 15 feet by 25 feet from about 40 houses”[16]. Most of the city’s several hundred yards were cleared as slums in the 1950s. All that remains of Rose Yard is the entrance and a few houses. (See Nick Stone’s brilliant rephotography of this area [17]).

Rose Yard #7 St Augustine’s Street

This entrance to Rose Yard can be seen (below) to the left of The Rose Inn as it was in 1938. An inn is known to have been on this site since the C14 when it refreshed those attending the jousting tournaments in Gildencroft.

The Rose Inn in 1938, with the entrance to Rose Yard on the left [www.georgeplunkett.co.uk]

St Augustine’s. In the background, a medieval terrace and a looming presence.

In the churchyard is the tomb of Thomas Clabburn (d.1858) who employed upwards of six hundred Norwich weavers [19].

The Clabburn family tomb. Inside the church is a tablet commemorating Thomas’s ‘many virtues as an employer and a kind, good man’

In the background (above) is Church Alley (1580), believed to be the longest row of Tudor houses in England [7]. It leads to the wonderfully named street, Gildencroft, which commemorates an area that once roughly overlapped St Augustine’s parish [20].

Gildencroft is also the name of a small park I circumnavigated as I tried to find the Quaker Burial Ground. I passed a small building, now a nursery, that was built by the Society of Friends at the end of the C17 then rebuilt after the original was destroyed in the 1942 Baedeker air raids. Nearby are the gates to the burial ground, which were open when I visited it this spring in search of Amelia Opie’s grave [20], but are now sadly locked. Reasons for closure include drink, drugs and dog poo (wasn’t that an album by The Pogues?).

The Quaker Burial Ground, Spring 2017

I completed my anticlockwise stroll around Gildencroft by walking through St Crispin’s Car Park and hopping up a bank to St Crispin’s Road (aka the ring road) with its busy roundabout. Due to the volume of traffic I had to trek back up Pitt Street (commemorating not Prime Minister Pitt but a rubbish pit [7]) to find a safe crossing. And it was here, now facing towards Sovereign House, that I was confronted by the source of my irritation – Anglia Square and all it stands for: postwar dereliction, the ring road, the Magadalen Street flyover, disregard of the pedestrian, insensitivity to the past … [22].

The derelict Sovereign House (formerly Her Majesty’s Stationery Office), part of the 1960s/70s Anglia Square development

In the decades after the war it must have seemed a good thing to replace a bomb-damaged area of insanitary medieval housing with Brutalist modernity. But modernity barely survived 50 years in the case of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, and the shopping centre fails to thrive. This can’t be blamed on a dislike of Brutalism in the provinces: see how well concrete works in Lasdun’s greenfield site at UEA. More likely the problem stemmed from the imposition of an out-of-scale development on an historic site. Now, in a frightening example of history repeating itself, it is proposed to replace Anglia Square with a tower block 25 storeys high [23].

The isolation of St Augustine’s from the city centre by the river had already established its marginal identity but then, in the 1960s and 70s, the severing of old routes by the inner ring road released this area into an even more distant orbit: Norwich-over-the-ring-road (Ultra Via Anulum). [See 24 for a critical view of ‘The Norwich Magdalen Street Massacre’].

I tried to get back to the city centre by walking under the flyover that goes on to blight the next radial road – medieval Magdalen Street – but found my way blocked by a private trailer depot …

… so I doubled back and left via the only route available to pedestrians going up or down Duke Street – an underpass. Flâneurs and flâneuses wanting to enter an historic area are unlikely to find a less welcoming entrance but do it, explore St Augustine’s and help reconnect it to the city centre.

©2017 ReggieUnthank

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fl%C3%A2neur

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychogeography

- Will Self and Ralph Steadman (2007). Psychogeography Pub: Bloomsbury.

- Laura Elkin (2017). Flâneuse. Pub: Vintage

- Frances Holmes and Michael Holmes (2013). The Story of the Norwich Boot and Shoe Trade. Pub: Norwich Heritage Projects

- Citizens of no Mean City (1910). A trade book published by Jarrold and Sons.

- http://www.staugustinesnorwich.org.uk/history_-_the_gildencroft.html. Do read this excellent account of the history of this area By S J McLaren. The website (http://www.staugustinesnorwich.org.uk/index.html) describes a proud community working hard to maintain its identity.

- Francis Blomefield, ‘The City of Norwich, chapter 15: Of the city in Edward III’s time’, in An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 3, the History of the City and County of Norwich, Part I (London, 1806), pp. 79-101. British History Online. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-hist-norfolk/vol3/pp79-101#p27

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (2002). The Buildings of England. Norfolk I, Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/02/15/the-flamboyant-mr-skipper/

- http://www.twa.co.uk/projects/the_lathes_norwich

- http://users.trytel.com/tristan/towns/florilegium/popdth04.html

- https://www.eastonpottery.com/about

- Peter Trudgill (2003). The Norfolk dialect. Pub: Poppyland, Cromer.

- http://www.nunnsyard.co.uk/exhibitions.html

- Frances Holmes and MichaelHolmes (2015). The Old Courts and Yards of Norwich. Pub: Norwich Heritage Projects. (The definitive book on the Norwich yards).

- http://www.invisibleworks.co.uk/lost-city-ghosts-st-augustines-the-rose-tavern/

- Mortlock, D.P. and Roberts, C.V. (1985). The Popular Guide to Norfolk Churches. No2 Norwich, Central and South Norfolk. Pub: Acorn Editions.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Augustine%27s_Church,_Norwich

- Personal communication, Stuart McLaren

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/03/15/three-norwich-women/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglia_Square_Shopping_Centre,_Norwich

- http://www.edp24.co.uk/news/environment/25-storey-tower-block-planned-in-new-anglia-square-development-for-up-to-1-350-homes-1-4929377

- http://nr23.net/govt/unfinished_mag_st.htm

Thanks. I am indebted to: local historian Stuart McLaren for sharing his deep knowledge of the area; to Rachel Kurdynowska for information about Easton Pottery; to The Bookhive (http://www.thebookhive.co.uk/) for suggesting Lauren Elkins’ Flâneuse; and Jonathan Plunkett for access to the website based on his father’s largely pre-war photographs (www.georgeplunkett.co.uk). I thank my daughter Susie for the many conversations about psychogeography and urban walking .

The Norwich Society helps people enjoy and appreciate the history and character of Norwich. Visit: www.thenorwichsociety.org.uk

Was the walk serendipitous or planned with the research following. A very interesting and inspiring article. Alan

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the comment Alan. The original idea was to walk a line from St Augustine’s Gate into the marketplace but there was so much to see in Gildencroft that I never completed the other half. I didn’t want to have preconceptions so the research followed.

LikeLike

Thanks Reggie. I really enjoy your posts. Yet another fascinating dip into the history and geography of Norwich.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for following Philip. I had driven through the Gildencroft area dozens of time but, of course, you only really start to see it on foot. Let’s hope it survives the next redevelopment.

LikeLike

Thanks Reggie – an excellent read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m pleased you liked it Paul. Remembering your church bench ends photos with admiration.

LikeLike

Thank-you so very much for this fascinating post, Reggie. I haven’t yet ventured this far north by foot in the city though I have driven round the area many times. I only recently found out what the developers plan to do to Anglia Square and was horrified by the prospect of the 25 storey tower block. I hope something is done about the flyover – getting rid of it altogether would be good! Thank-you for the introduction to Nick Stone’s work and website and also to psychogeography, of which I’d never heard!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s a great pity that the ringroad and the river conspire against poor St Augustine’s. I just hope the new development, when it comes, doesn’t inflict further damage. And isn’t Nick Stone’s site terrific? Reggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

From Stuart McLaren. Thanks for the name check, Colonel U. Anyone wanting to find out more about this fascinating and unjustly overlooked quarter of the city may do so at http://www.staugustinesnorwich.org.uk A of minor quibble. The Jousting Acre (and Folly Ground) was on the south side of the city wall.The photo mainly shows what would have then been the wall’s north ditch, unsuitable for jousting at any time as probably mostly full of smelly water, dead cows and household muck. N.B. I help run a local walking group that meets at the Cactus Café in Magdalen Street each fortnight to explore the “psychogeography” of Norwich Over the Water. Seek us out on ye olde Facebook under “Magdalen Walks”.

LikeLike

Thank you for the informative comment Stuart. Corrections made.

LikeLike

Pingback: Reggie through the underpass | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The Pastons in Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Nairn on Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Twentieth Century Norwich Buildings | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH