Coats of arms designed to identify groups of soldiers in the heat of battle were also used by towns and cities to identify themselves and the source of their authority.

Both symbols on the Norwich coat of arms are martial and point to a long relationship with the crown that conferred certain privileges upon the city. This civic coat of arms is described as: “Gules, a castle triple-towered and domed argent; in base a lion passant guardant Or”. Simply put: red shield, silver castle, gold lion. There are, however, many stylistic variations: as often as not the triple-towered castle isn’t domed.

Undomed or domed. The Norwich City coat of arm in the City Hall (1938). Left, on the Bethel Street door to the Treasurer’s Department and right, inside the ‘Rates Hall’.

The castle, of course, is Norman but it was about a century after the Conquest that the city’s lion appeared during the reign of the Plantagenets. The association between the lion and the English crown seems to have begun during the reign of King John but it was John’s older brother, Richard the Lionheart, who is particularly associated with the lion passant guardant [1]; that is, walking with forepaw raised (passant) and head turned to the left, full face (guardant). This is the version of the animal that figures on all of the city’s heraldic devices. Except … guarding the entrance to the City Hall, Alfred Hardiman’s Assyrian-influenced bronze lions are two of our finest civic sculptures but they are at odds with other Norwich lions in not looking left. This may be because the architects saw a lion exhibited at the British Empire Exhibition of 1936 before they commissioned its twin [2].

Staring straight ahead, one of Alfred Hardiman’s lions (1938) outside the City Hall [3]

The connection with Richard I relates to the charter of 1194 in which he allowed citizens to elect their own Reeve – equivalent to the ‘president’ of the borough [4]. The foundation of self-government is usually dated to Richard’s charter even though there may have been a degree of municipal independence before this [5].

The Guildhall, which is the largest medieval civic building outside London, was built 1407-1412 in order to administer the self-governing powers conferred upon the city by Henry IV. The king’s charter of 1404 granted county status to the city and, like London, allowed the citizens to elect a mayor [6]. Documents issued by the council were authenticated with the city’s coat of arms in the form of a wax seal applied either directly or pendent.

Left and right: early C15 wax seals from Colman’s Collection Norfolk Record Office COL5/1. Centre: “The Common, or City Seal, now in use” Blomefield 1806 [6]

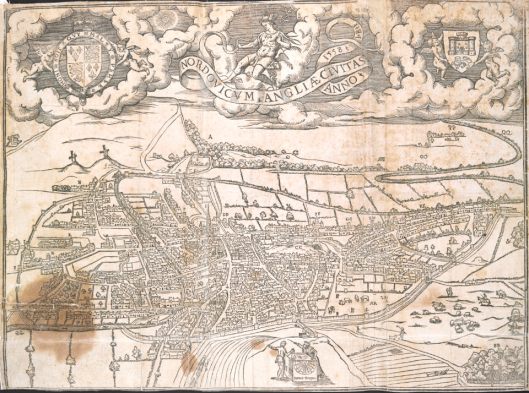

The city’s proud status as ‘civitas‘, a form of city state, is acknowledged in Cuningham’s 1558 map of Norwich, which is probably the earliest surviving printed map of any English town or city.

Map of Norwich by citizen William Cuningham, ‘Doctor in Physicke’ 1558 (British Library)

In the top right corner we can see the castle and lion augmented by two supporters who, as we will see, appear in various guises through the city’s history.

A century prior to this, around 1450, the alderman John Wighton – whose stained glass workshop made the great east window of St Peter Mancroft – glazed the window of the council chamber in the Guildhall. He did this for the mayor and wealthy wool merchant Robert Toppes who ran his business from Dragon Hall in King Street [see 7 for a fuller account of the Norwich School painted glass].

A century prior to this, around 1450, the alderman John Wighton – whose stained glass workshop made the great east window of St Peter Mancroft – glazed the window of the council chamber in the Guildhall. He did this for the mayor and wealthy wool merchant Robert Toppes who ran his business from Dragon Hall in King Street [see 7 for a fuller account of the Norwich School painted glass].

Between the two angels is Toppes’ own coat of arms, dwarfing the city coat of arms beneath each angel.

City coat of arms mid C15, from the Toppes window in the Guildhall

Opposite the rear entrance to Cinema City, the city arms can be seen amongst a series of 13 shields carved at the east end of St Andrew’s church and dated to the rebuilding of the church 1500-1506.

Norwich arms on St Andrew’ Church ca 1505. Note the simplified castle and the contrary lion

A fine C16 example of the city coat of arms can be seen in Surrey House, the early C20 building designed for Norwich Union by George Skipper. The stained glass is a relic from the Earl of Surrey’s house that previously stood on this site in what is now Surrey Street.

From the Earl of Surrey’s C16 house in Surrey Street, Norwich

The Earl of Surrey, Henry Howard, son of the Duke of Norfolk, was called “the most foolish proud boy that is in England” and it was pride that led to his downfall. Surrey was brought up in Windsor Castle with Henry VIII’s illegitimate son Henry Fitzroy. The king came to believe that Surrey – a staunch anti-Protestant – was planning to usurp Henry VIII’s legitimate son, Edward VI, when he inherited the crown. The trigger, though, appeared to be when Surrey flaunted his descent from English royalty by attaching (quartering) the arms of Edward the Confessor to his own. He was executed for treason in his thirtieth year but his father, who was to have shared that fate, was saved when Henry VIII died the day before the planned execution [8].

Against this background of excessive pride associated with coats of arms, the other armorial glass in the Ante Room of Surrey House [9] takes on an extra layer of meaning.

Around 1900, three marble mosaics of the city arms were installed in the entrances to civic buildings: the Guildhall, Norwich Castle and the Technical Institute (now Norwich University of the Arts). But I can find no record of the Italian craftsmen living around Ber Street who were reported to have made them.

On the south side of the Guildhall is the Bassingham Gateway, originally from the London Street house of John Bassingham, a goldsmith in the reign of Henry VIII. When London Street was widened in 1855-7 the gateway was bought by William Wilde for £10 and inserted in the Magistrate’s Entrance of the Guildhall [10].

By comparing this with George Plunkett’s 1934 photograph of the doorway [10], the crisp carving would appear to be part of a postwar renovation. The lion is now decidedly oriental.

Although there are minor variations in the way they are depicted, the castle and the lion are constants in the city’s arms. More variable are the supporters – the flanking figures that appear on some versions of the arms. In Cuningham’s map of 1558 (above) they appeared as cherubs.

In 1511 the roof of the mayor’s chamber in the Guildhall collapsed and in the rebuilding of 1535-7 the chequerboard of the eastern façade received coats of arms; the city arms of castle and lion were protected by armed angels and an indeterminate shape hovering over the shield [3].

The city arms; one of three coats of arms on the east end of the Guildhall. (The central arms [not shown] were those of Henry VIII but are no longer legible)

Above this coat of arms on the east wall is a clock turret dated 1850, dedicated to mayor Henry Woodcock. Flanking the clock face are two unarmed angels, each clasping the city arms.

Curiously, the gilded inscription at the lower edge of the clock gives the motto of the Dukes of Norfolk (Sola Virtus Invicta, Only Virtue is Invincible) who, for a long time, had had no connection with the city or county [3]

An illustration in Blomefield’s authoritative book on the history of Norwich [6] also has two angels as supporters, this time armed, but the object above the shield is difficult to read in this form.

The Arms of the City of Norwich. From Blomefield [7] 1806

Hudson and Tingey’s 1906 book on Norwich history [4] also shows the shield flanked by two guardian angels and in this case the object above the arms resolves as a hat. One source describes this as a warden yeoman’s hat (yeoman warder’s?) [2], another as a fur cap [12]. (After posting this article, former Sheriff Beryl Blower told me this may be the mayor’s ceremonial Cap of Maintenance and I see that Blomefield says that the cap of maintenance is worn by the sword-bearer on all public occasions).

The Norwich City Arms embossed on the cover of Hudson and Tingey, 1906 [4]

The hat also appears on the blue lamp on the police station, which is attached to the west side of the City Hall, but no guardian angels.

Police Station, Bethel Street 1938

The City Hall itself is Coat-of-Arms Central; there were even plans for the tower to be topped with an angel before it was cut for reasons of cost [3]. The city arms appears above the entrance to the City Treasurer’s Department in Bethel Street with all its accoutrements: the hat and Art Deco angels flanking a traditional coat of arms.

By Eric Aumonier who also designed Art Deco sculpture for the London Underground

Examples of the ‘full set’ can also be seen on the engraved glass window above the stairs leading up from the ground floor of the City Hall…

Designed by Eric Clarke and painted by James Michie [13]

… and on Lutyens’ war memorial, facing the City Hall on St Peter’s Street.

The additional elements (hat and angels) that appeared some time after the original granting of the lion-and-castle arms do complicate what was once a simple and effective design. The College of Arms does not recognise the the flanking angels; by dispensing with the supporters the cartoon-like arms on these two mid-C20 projects marked a return to simplicity (although the question of whether or not to dome the castle is still not solved).

Domed or undomed. Left, Hewitt School; right, Alderson Place, Finkelgate. These two civic projects were supervised by City Architect David Percival ca 1958

The right-hand version of the city arms also appears on Percival’s 1960 redevelopment on Rosary Road.

Added 5/10/18

© 2018 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lion_(heraldry)

- Nobbs, G. Norwich City Hall (a booklet from the City Hall, private imprint and undated but published for the 50th anniversary of the 1938 opening).

- Cocke, R. (2013). Public Sculpture of Norfolk and Suffolk (photography by Sarah Cocke). Pub: Liverpool University Press.

- Hudson, W. and Tingey, J.C. (1906). The Records of the City of Norwich vol 1. Pub: Jarrolds.

- Meeres, F. (2011). The Story of Norwich. Pub: Phillimore & Co Ltd.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norwich_Guildhall

- Blomefield, F. (1806). An essay towards a topographical history of the County of Norfolk. Vol III Containing the History of Norwich. Pub: W Miller, London.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2015/12/19/norfolks-stained-glass-angels/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Howard,_Earl_of_Surrey

- http://www.norfolkstainedglass.co.uk/Norwich_Union/ante_room.shtm

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/guildhall.htm

- http://www.ngw.nl/heraldrywiki/index.php?title=Norwich

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1210484

Thanks to Clive Cheesman, Richmond Herald of the College of Arms for information about the Norwich coat of arms.

Hi Reggie. Another great article. One thing it would be interesting to know more about is the dome. It’s present in the formal description you give but is largely absent from the representations. I’d be tempted to say it’s a later addition, but you give a 16th cent example above (the Surrey window). It’s interesting that the last two examples from the ’50s are nearly identical although one appears to have the domes while the other tops it with a more pleasing flag that mimics/mirrors the lions tale. Grant

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Grant, That’s a very interesting point. It is surprising that “a castle triple-towered and domed argent” is not often represented as domed. Nearly every representation of the castle shows some kind of variation so artists clearly feel free to do their own thing. I particularly like your point about the final C20 pair of arms, virtually identical except that one castle isn’t domed and the whiplash tail of one lion is mirrored in the pennant flying from the castle tower. I’ll update accordingly. Reggie

LikeLike

Fascinating and so much fun! Thank you for a great read, Reggie.

LikeLike

Thank you Katherine

LikeLike

Fantastic post, Reggie! I learn so much from your essays.

LikeLike

I appreciate your comments Clare

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure.

LikeLike

Great article, keep em coming!

LikeLiked by 1 person

There were so many coats of arms it was hard to know which to leave out. Thanks for the comments Simon

LikeLike

Funny how I knew all this stuff, but didn’t. Thanks for joining the dots!

LikeLike

I know. The old coat of arms seems so commonplace but behind it is a real depth of history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reggie – a really interesting and thorough story – as ever. I learnt a lot, not least re the angels, the Woodcock clock and City Hall.

I would only comment that re the window in the Guildhall Mayor’s Court Room, I think you imply that the window you show – actually the left hand one of three, seen from inside – is an original whereas, as I understand it, all the glass in the room is a hotch-potch of periods, some from the original glazing, some from St Barbara’s Chapel in the Guildhall, and some Tudor – after the ceiling rebuilding – and C17th up to the C19th. I think you also imply that the Toppes arms comprise the whole of the image you show whereas I’m sure that his arms are only a small part, viz. the bit with the three spinning tops (his rebus).

Your mention of the ‘hat’ above the various arms is very interesting and rarely mentioned. I think it’s the ‘Cap of Maintenance’, shown most clearly on the Luteyns memorial. It’s also shown very prominently in a carving with the civic mace and sword at the centre of the Georgian columns which provide a grand entrance to the Mayor’s Court Room etc on the landing. I have a photo. I think you suggest that somehow it’s crept into the city arms but is not original.

The meaning of it seems a bit obscure but it seems to symbolise royal authority- delegated to the Mayor. Wikipedia has quite lot on it and also I found this: ‘it derives from the reign of Henry VII when it was presented to the King by the Pope in recognition of the King’s secular supremacy. It is only worn once by a sovereign on the occasion of the coronation’ (.http://lordsoftheblog.net/2010/05/25/the-cap-of-maintenance/ ). So we’re still pretty Catholic, it seems!

Richard Matthew

richardmatthew24@gmail.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Richard, Thank you for your most interesting comments. I seem to keep coming back to the Toppes window in the Guildhall – it was in my very first post. The glass is certainly a jumble, having been likely affected by the Great Blow (C17 explosion) and, as you say, by the later collapse of the ceiling and of the east wall. But you can still pick out the C15 glass that John Wighton’s workshop made at the time that Toppes was mayor. In my next post I shall be comparing one of the angels from that window with an angel in the great east window of St Peter Mancroft drawn from the same cartoon.

The cap of maintenance was a bit of a puzzle and I only came to know it as that when, after I published the article, former Sheriff Beryl Blower put me in the picture; I included that information in the present updated version. I just wish I’d seen the Wikipedia article since it described it nicely: “… in early borough charters granting the right to the use of a ceremonial sword which often mentioned in addition the right to a Cap of Maintenance. However, this was intended to mean that in civic processions a Cap of Maintenance should be carried along with the Sword (and Mace), signifying that the Mayor was the Sovereign’s representative.” When I enquired, the College of Arms didn’t recognise either the angels or the cap of maintenance as part of the official city arms but knowing that the cap can be traced back to Henry Tudor there must have been a great temptation to use it. (But on his city map of 1558,some 50 years after Henry VII died, Cuningham evidently did avoid the temptation, supporting the idea that the additions were optional).

Thanks again Richard, Reggie.

LikeLike

More on the Cap of Maintenance:

1) Do you or anyone else know what the ‘Maintenance’ refers to? I have a dim memory of maintenance referring to taxation.

2) Interestingly in Blomefield’s account of Queen Elizabeth’s visit in 1578 it is the ‘hat of maintenance’:

‘Then followed the officers of the city every one in his place; then the swordbearer with the sword and hat of maintenance; then the mayor and 24 aldermen, and recorder, all in scarlet gownes, whereof so many as had been mayors of the city, and were justices, did wear their scarlet cloaks’. (https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/History_of_Norfolk/Volume_3/Chapter_27).

Richard Matthew

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the fascinating addition to the ‘cap of maintenance’ question. I’ll throw it out to visitors; anyone? Best wishes, Reggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The absent Dukes of Norfolk | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Thanks for another interesting read Reggie. About the contrary lion on St Andrews: I was told on a City tour that all the lions face the altar on that wall.

LikeLike

Thank you for the kind comment Christopher. This sounds fascinating and I would like to hear more. It would be good to know what was gained by reorienting the ‘Norwich’ lion left-right and then turning his head outwards, away from the altar on the other side of this wall. Reggie.

LikeLike

Hello David, In a trade book, I see a painting submitted to the Royal Academy in 1903: the N&N Savings Bank is adjacent to Skipper’s Commercial Chambers and both appear as they do today. Am I right in thinking that your discussions suggest that this bank of Skipper’s on Red Lion Street was originally intended for Stump Cross and that Stump Cross ended up with the now-demolished two-storey building? I’d love to see any material/references you have on this. Kind regards, Reggie.

LikeLike

Pingback: Parson Woodforde goes to market | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Maybe slightly going off at a tangent, but my Great Aunt Nellie was married to Thomas Boston, who ran a gentleman’s outfitters on Orford Place. His brother William Thomas Boston, who also came from Norwich, became sword bearer to the Lord Mayor of London in the 1950s and there are photos of him on the internet wearing the fur cap that you mention.

https://www.shutterstock.com/editorial/image-editorial/the-city-sword-bearer-william-thomas-boston-and-the-common-cryer-sergeant-at-arms-commander-jrpoland-carrying-the-mace-3027859a

LikeLike

Liz, I remember Boston’s farmer’s outfitters in Orford Steet and when I came to Norwich in 1982 bought a pair of baggy corduroy trousers. The fur cap you mention is wonderful. It’s the best example I have seen of the ‘Cap of Maintenance’ in use by the sword bearer. I would like to insert into the old blog on the topic but the cost is prohibitive (but can still be seen via Liz’s link). Many thanks for this, Reggie

LikeLike