The face is the most important part of one’s identity. It conveys a visible expression of personality and can used in art to evoke a range of emotions. But at a time when faces were not universally recognised other symbols could be used to underline identity.

“The face is a picture of the mind with the eyes as its interpreter.” (Cicero)

I was reminded of this by the painted rood screen from St Mary’s North Elmham. Despite having their faces scratched in the reign (probably) of Edward VI the rather mournful saints, Barbara, Cecilia and Dorothy (Babs, Cissy and Dot) can still be recognised to be portraits of the same woman. But likeness to long-departed saints is hardly the point here; instead, beauteous Barbara is identified by the tower in which she was hidden from the world, Cecilia’s virginity is signified by her wreath of lilies, and Dorothy (patron of gardeners, amongst others) holds a bunch of flowers. The face is incidental to the virtue signified.

Rood screen, St Mary’s North Elmham, Norfolk (ca 1474) saved from destruction by being used as floorboards. SS Barbara, Cecilia and Dorothy

In the late medieval period Norwich was a major centre for glass painting and the often stereotypical faces of saints and angel can be recognised throughout East Anglia [2, 3]. The same faces appear in various guises suggesting they were drawn from the same cartoon. For example, the angel from the Toppes-sponsored windows in St Peter Mancroft can be overlaid pretty faithfully upon the saint from the ‘Toppes’ window in Norwich Guildhall. Both were painted ca 1450 by the workshop of John Wighton, in which his wife and son also worked [4].

Left, St Peter Mancroft; right, Guildhall; centre, overlay

A wonderful sequence of images from the late C15 is to be found in the chantry chapel of St Helen’s in the Great Hospital, Norwich. These roof bosses may have escaped desecration because Henry VIII’s zealously Protestant and iconoclastic son, Edward VI, handed over control of the chapel to the mayor, sheriff and citizens of Norwich [1].

Two faces are reputed to be of Queen Anne of Bohemia and her husband King Richard II, but the evidence is slender. The woman does wear a hard-to-see crown: the man does not, but then he was usurped [1].

Reputedly, Queen Anne of Bohemia and King Richard II

Queen Anne and her husband visited Norwich in 1383 but by the time Bishop Goldwell (rebus, a golden well) …

… had this vaulted ceiling built (ca 1472-1499) the couple had been dead a century. In the glorious Wilton Diptych, Richard II kneels clean-shaven before the Virgin. So if the boss of the hirsute man is meant to represent Richard then it may not be a likeness but a representation of deposed majesty, wearing a headband instead of a crown.

The Wilton Diptych 1395-9. National Gallery

Norwich Cathedral has over 1000 bosses carved into the keystones of its roof vaults – more than any other religious building in the world. In the cloisters are several of the Green Man – a pagan figure representing, perhaps, the rebirth of nature. However … just as the term ‘ploughman’s lunch’ seems to have been a fiction concocted by The Cheese Bureau (surely a Philadelphia soul group?) as recently as the 1950s, so – it is claimed – the term ‘Green Man’ as applied to church roof bosses can only be traced back to an article by Lady Raglan in 1939 [quoted in 5]. Can this be right? Anyway, the faces can be classified as: a ‘leaf mask’ made from a single leaf; a ‘foliate face’ made from several leaves; ‘disgorgers’, with leaves or vines exiting mouth, ears, nose; this one seems to be a ‘peeper’ or ‘watcher’.

A face peeps out behind the leaves in the cloisters of Norwich Cathedral (1316-19)

Roof bosses also decorate the vaulting inside St Ethelbert’s Gate to the Cathedral. The present gate was built ca 1316 (restored in 1815 and 1964), incorporating the remains of the Norman gate burnt in the riots of 1272 [6]. The conflict centred on a jousting target (quintain) in Tombland at which two priory men were detained. The prior replied by bringing in armed men from Yarmouth who went on the rampage; the citizens, in turn, attacked the priory, set fire to St Ethelbert’s Gate and parts of the cathedral itself were set ablaze. Thirteen of the prior’s men were killed but King Henry III, who came from Bury St Edmunds to restore order, put 35 citizens to death: by dragging some behind a cart; by hanging, drawing and quartering others; and by burning alive a woman who set fire to the gate. To compensate the priory the citizens were required to fund the rebuilding of the gate. The naturalistic head on the boss looks down with distaste.

The Despenser Retable survived the Reformation by being inverted as a table top. Now, this altarpiece can be seen in St Luke’s Chapel in Norwich Cathedral. One intriguing hypothesis is that this late medieval treasure was commissioned by Henry le Despenser, the ‘Fighting Bishop’ (1370-1406), to mark the suppression of the Peasant’s Revolt by Richard II and perhaps his own part in the East Anglian skirmishes [7]. Incidentally, the rich red colour in the painting was known as ‘Norwich Red’ and was later used in the city’s famous C18 shawls [7].

The Despenser Retable, Norwich Cathedral

The first panel depicts the Scourging of Jesus. Pilate’s representative handles Jesus’ hair while the face of the man holding the scourge is “contorted with the effort” [7] of delivering the punishment (out of shot, both his feet spring off the ground).

On Agricultural Hall Plain, between the Hall (‘Anglia TV’) and Shirehall, is George Wade’s memorial. Unveiled in 1904, ‘Peace’ records the 300 Norfolk men who served in the Boer War. The mood, subdued rather than victorious, is conveyed by the angel’s neutral expression as she sheathes her sword [8].

‘Peace’, George Wade’s Boer War memorial on Agricultural Hall Plain (1904)

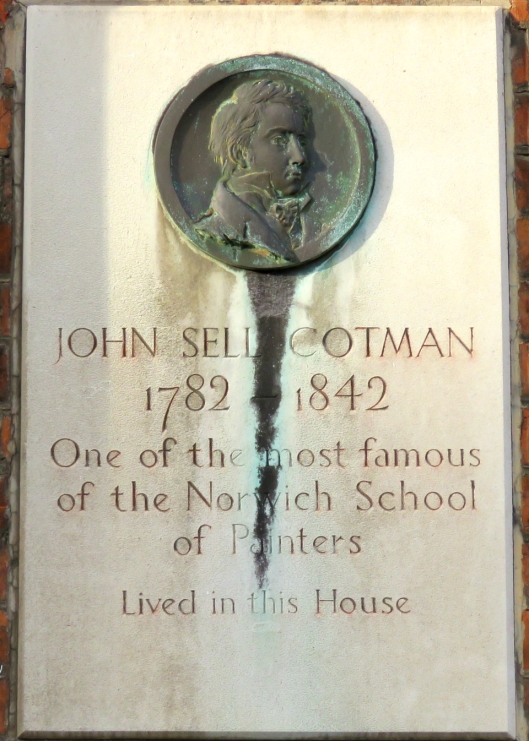

In St Martin-at-Palace Plain, next to the Wig and Pen pub, is Cotman House. One of the city’s favourite sons, the painter John Sell Cotman, lived here from 1823 to 1834. If he had been born in London rather than the provinces an artist of Cotman’s stature would surely have been commemorated in Westminster Abbey.

JS Cotman by Hubert Miller 1914 [8]

Cotman House, where John Sell Cotman opened his ‘School for Drawing and Painting in Water-colours’ [9]

Magdalen Street and nearby Colegate have a good number of late medieval and Georgian doorways [see 10, 11]. Pevsner and Wilson judged No. 44 to be the climax of Magdalen Street, with “one of the most ornate Georgian façades in Norwich.” [12]. George Plunkett wondered if the doorway might have been constructed to designs by Thomas Ivory, architect of The Assembly Rooms and the Octagon Chapel [13]. The keystone on the arch is decorated with a classically-influenced head.

The closed eyes of the head suggest a death mask: the ostrich feathers in the figure’s hair signify a woman of fashion [14].

At the beginning of the C20, Norwich architect George Skipper played with a variety of influences, including Art Nouveau [15], but for the city’s banks and insurance companies he used a Neo-Classical Palladian style, adding seriousness with borrowed classical motifs. Above the door of the London and Provincial Bank in London Street (now The Ivy) is a female head [8]. The mild erosion makes it difficult to confirm whether she wears a garland, synonymous with Flora the Roman goddess of flowers and Spring. However, the swags of fruit at the putti’s feet convey the required air of prosperity.

The same year (1906), Skipper commissioned similar stone sculpture for the Norwich and London Accident Assurance in St Giles Street (currently St Giles Hotel). Once more, a sense of prosperity is conveyed by the swags of fruit and flowers.

Although the androgynous head bears a laurel wreath, rather than flowers, the festoons of fruit and flowers again are indicative of Flora. For the later (1928-30) Lloyds Bank on Gentleman’s Walk by HM Cautley, a similar head was used, decorated with a mini-swag of finely carved flowers. Richard Cocke suggests this is a direct tribute to Skipper’s London and Provincial Bank around the corner [8].

For the later (1928-30) Lloyds Bank on Gentleman’s Walk by HM Cautley, a similar head was used, decorated with a mini-swag of finely carved flowers. Richard Cocke suggests this is a direct tribute to Skipper’s London and Provincial Bank around the corner [8].

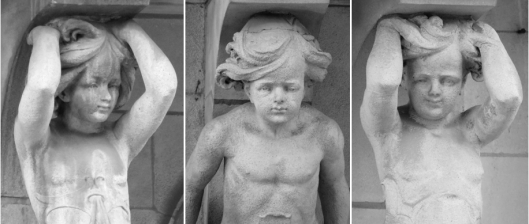

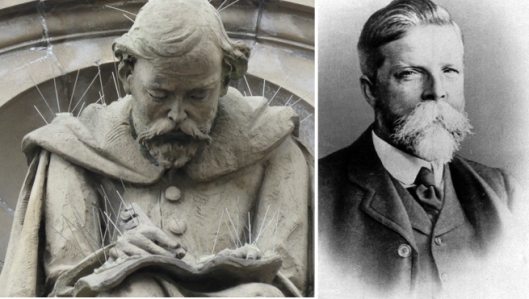

Nearby, on Red Lion Street is another Skipper building, Commercial Chambers built in 1903 [15]. The facade is almost riotously decorated in buff terracotta (probably Doulton). The first floor cornice is supported by two boys and a girl, almost certainly sculpted from life, making a change from the usual putti.

Crowning the building is a cowled figure making entries into a ledger with a quill. This might reasonably be thought to represent the owner, the accountant Charles Larking; but as we saw previously it is clearly modelled on the architect himself [15].

At about the time that Skipper was designing these buildings, his pupil J. Owen Bond – who was responsible for some of the few Modernist buildings in the city – designed the Burlington Buildings in Orford Place (1904). Instead of female heads, the building was decorated with three pairs of full-length, reclining women: one of each pair reading a book, the other holding a cornucopia.

‘Burlington Buildings’ was built for offices rather than for a bank or insurance company. Unfortunately, this fine Renaissance-style building is hard to appreciate, being rather hemmed in at the back of Debenhams.

The Horn of Plenty is not especially associated with Flora and could just as well refer to Concordia (goddess of Peace and Harmony), Abundantia (Abundance personified) and Fortuna (Luck and Fortune). In architecture it seems that the symbolism of plenty may be more important than adherence to any particular goddess.

This can be seen on the bases that James Woodford sculpted for the flagpoles in the memorial gardens outside the City Hall [16]. Each base shows an Assyrian-influenced priestess holding an overflowing basket. Woodford’s references to the two-dimensional paintings and reliefs from the Assyrian and Ancient Egyptian empires are entirely fitting outside a City Hall that shunned Gothic and Classical motifs in favour of Modernism. As in Egyptian art, the figure presents a combination of frontal and profile views. With the head in profile it is difficult to express emotion; it is the associated animals and plants that bear the symbolic load, celebrating the region’s agricultural abundance.

A celebration of Agriculture by James Woodford (1938), who also sculpted the 18 roundels celebrating Industry on the City Hall’s bronze doors [8].

©2018 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- Rose, Martial. (2006). A Crowning Glory: the vaulted bosses in the chantry of St Helen’s, the Great Hospital, Norwich. Pub: Lark’s Press, Dereham.

- Woodforde, C. (1950) The Norwich School of Glass-Painting in the Fifteenth Century. Pub, Oxford University Press

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2015/12/19/norfolks-stained-glass-angels/

- King, D. J. (2006) The Stained Glass of St Peter Mancroft, Norwich, CVMA (GB), V, Oxford.

- https://thecompanyofthegreenman.wordpress.com

- Meeres, Frank (2011). The Story of Norwich. Pub: Phillimore and Co Ltd. (A highly readable account of the city’s history).

- McFadyen, Phillip (2015). Norwich Cathedral Despenser Retable. Pub: Medieval Media, Cromer.

- Cocke, Richard (with photography by Sarah Cocke) (2013). Public Sculpture of Norfolk and Suffolk. Pub; Liverpool University Press. (An essential source for anyone interested in East Anglian sculpture).

- Kent, Arnold and Stephenson, Andrew (1949). Norwich Inheritance. Pub: Jarrold and Sons Ltd

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/06/16/entrances-and-exits-doors-ii/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/05/26/early-doors-tudor-to-georgian/

- Pevsner, Nikloaus and Wilson, Bill (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk I, Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/mag.htm

- https://janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/2010/12/05/regency-fashion-how-a-lady-accommodated-her-head-feathers-at-the-end-of-the-18th-century/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/02/15/the-flamboyant-mr-skipper/

- http://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/person.php?id=msib2_1208277486

Thanks. Chris Walton writes the very informative Company of the Green Man website [5] and I am grateful to him for information on foliate faces. I thank Revd Dr Peter Doll, Canon Librarian of Norwich Cathedral for permission to photograph the Despenser Retable and Dr Roland Harris, Cathedral Archaeologist for information on the cathedral bosses and the Ethelbert Gate.

Bonus track

Nelson with his favourite alpenhorn

Unfortunately, the surface on this statue of Admiral Lord Nelson by Thomas Milnes (1852) – which is situated in the Upper Cathedral Close – is now quite worn and has lost much of its detail [8]. This, combined with its north-facing aspect, doesn’t favour photography but I couldn’t omit Norfolk’s most famous son, albeit ‘below the line’.

Thanks for that, I really enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Lynne, you take the prize for the fastest response 🙂

LikeLike

I love you Reggie! I can’t wait until the summer when I’m back in Norfolk. Norwich will seem like a different city thanks to your insight, research, and joy of the place. I forgot how such a wonderful, almost perfect, piece of public sculpture George Wade’s ‘Peace’ is. Thanks again for another wonderful surprise in my dull inbox.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I feel the love Daniel. Truly delighted to receive such positive feedback.

LikeLike

An absolutely fascinating subject – and what a wonderful array of examples! I love them all – though the “Peace” angel’s expression is especially lovely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Katherine, Isn’t it strange: I had passed this statue on a busy crossroad hundreds of time but only ‘saw’ it when I took a photo. The angel is quite beautiful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for another great post. You open our eyes to the world around us.

LikeLike

I really appreciate the kind comment Philip. Best wishes, Reggie

LikeLike

Another thought provoking post. The Boer War memorial is best seen from the top deck of the open-top tourist bus. All Norwich residents should travel on it at least once!

LikeLike

Hi Don, It’s a great statue but – as you say – hard to see ‘properly’. Just off to catch the tourist bus.

Toodlepip, Reggie

LikeLike

I enjoyed this post so much, Reggie. I have seen a number of the faces you have highlighted already but now need another walk round the city looking for the others. I appreciate all the careful research you do and love all your detailed photos.

By the way, I have bought ‘Colonel Unthank and the Golden Triangle’ – a great read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Having reread this post particularly the ‘Green Man’ section I referred to my trusty 1854 Directory of Norfolk and there in Rackheathwas (and still is probably – haven’t been in it for years) the ‘Green Man’ kept by John William Clark, so the term was in use then, though of course it could refer to something totally different. Another topic for research on a wet afternoon.

LikeLike

Hi Don, Amongst Greenman-ologists there seems to be some debate about how the various incarnations of the green man relate. I quote from The Company of the Green Man website [ref 5]: “Green Men seem to have been referred to generally as “foliate faces” up until Lady Raglan coined the term “Green Man” in her article “The Green Man in Church Architecture”, published in the “Folklore” journal of March 1939. She thought that the Green Man of churches and abbeys was one in the same with “the figure known variously as the Green Man, Jack in the Green, Robin Hood, the King of the May, and the Garland who is the central figure in the May Day celebrations throughout northern and central Europe.” Many people still support these connections, believing that the Green Man has many faces and that each of these do indeed have deep seated and possibly spiritual links via an ancient race memory of a time when the Greenwoods covered most of what is now Britain”. I liked your comment, which shows that the term Green Man has been in currency for quite some time. I’ll contact the author and keep you posted. Best, Reggie [pleased you like the book].

LikeLike

Don,

Chris Walton who runs the Green Man website said this: “Green Man was definitely in circulation prior to 1939 but I have seen no evidence that it was used to refer to foliate faces. It was however definitely used for a pub name as detailed on my web site “The Green Man as a pub name may have a number of sources beyond that of the Green Man of church and folklore, including from the Green Man and Still heraldic arms used by the Distiller’s Company in the seventeenth century. Some pub signs will show the green man as he appears in English traditional sword dances (in green hats). Or as the Wild Man associated with drinking and revelry and usually carrying a club. There is also a strange interconnection between the Green Man and Robin Hood. Indeed some Green Man pubs changed their signs to foresters or Robin Hood from shaggy green men used as a symbol of the Distillers’ company in the 17th century.”

LikeLike