Tags

One of Norwich’s well-rehearsed claims is that it was first (1608) to establish a library in a building owned by a corporation and not by church or school [1,2].

Before this, most libraries were monastic. Norwich Cathedral Library was destroyed twice: first by citizens in the Tombland Riot of 1272 then again during Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries (1538) [3].

The Ethelred Gate to the Cathedral was rebuilt by the citizens in compensation for the riots (restored C19). The armed man and dragon in the spandrels, a common symbol for warding off evil spirits from gatehouses, may also allude to the Tombland Riot.

Before the advent of printing (ca 1450), the volumes would have been manuscripts, hand-written on parchment. From the original cataloguing marks, Ker [4] estimated that 120 of about 1350 pre-Dissolution books remain in the Cathedral Library. Other Norwich books ended up in Oxford and Cambridge including the spectacularly illustrated Psalter given to the Priory in the 1330s by the Norwich monk, Robert of Ormsby .

In the margin a cat stalks a rat in a hole. Ormesby Psalter ca 1310. Bodleian Library Oxford (bodley30.bodley.ox.ac.uk)

Another Norfolk treasure of the C14 is the Gorleston Psalter, once in Norwich Cathedral Priory now in the British Library.

A strangulated ‘queck’. Gorleston Psalter, British Library

Norwich Cathedral Library today

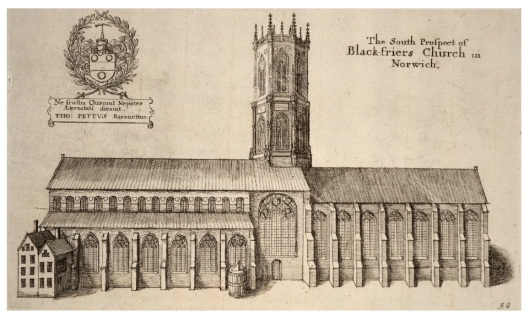

After the Dissolution, the city assembly agreed in 1608 that three rooms in the ‘New Hall’, which were rented to its sword-bearer, Jerrom Goodwyne, should be converted into “a lybrary for the use of preachers, and for a lodging chamber for such preachers as come to this cittie”[1]. This stood at the south porch of St Andrew’s Hall – part of the medieval Blackfriars complex that passed into the city’s hands after the Dissolution.

‘South Prospect of Blackfriers Church’ by Wenceslas Hollar (1607-1677). We know this – minus the tower – as St Andrew’s Hall (left) and Blackfriars’ Hall (right), comprising ‘The Halls’. The City Library was housed in the adjoining building, hard by the porch; lower left.

The donors’ book gives the founder of the library as Sir John Pettus (c1549-1614), the Mayor in 1608 [5].

Sir John Pettus Mayor 1608. Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Collections

Although he bequeathed a small collection of books to the library Pettus left no funds for its further development. This seems to have set the pattern for the piecemeal acquisition of books down the years for there is little evidence that the Assembly paid for anything other than the occasional volume [2].

Sir John Pettus Monument. SS Simon and Jude, Elm Hill, Norwich. Courtesy of [5]

Post-Reformation, the foundation of a City Library could be viewed as part of the transfer of knowledge and power from Church to local government but this was no secular enlightenment for the library was set up to provide lodging for itinerant Puritan preachers. At the invitation of the city administration, preachers delivered the Word at the ‘green yard’ in the Cathedral precinct [1, 2], their sermonising assisted by the wide range of sectarian tracts at the lodging place [2].

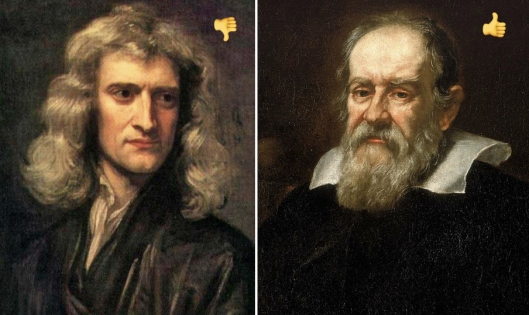

After some years of neglect the Old City Library was re-founded in 1657 by which time its scope had broadened to include secular topics such as philosophy, law, mathematics, maps, county guides etc. Donations were evidently eclectic: the library did not possess Newton’s monumental Principia (gravity, laws of motion) but it did have Galileo’s System of the World [2] in which he supported Copernicus’ observation that the earth rotated around the sun and not vice versa. For expounding this heretical idea Galileo was placed under house arrest by the Inquisition in his home near Florence. The presence of Galileo’s System in the Norwich City Library illustrates a more liberal climate in Protestant Europe.

No works by Newton but the City Library contained a revolutionary volume by Galileo. (Newton, after Godfrey Kneller, 1689; Galileo by Justus Sustermans, 1636)

The extraordinary degree of self-government granted to the City of Norwich over the years by the crown generated a sense of independence and radicalism. Political nonconformity was accompanied by a rise in dissent against the established church and by the early C18th 20% of the city’s population were Protestant dissenters [6]. Prominent among these was the surgeon, Philip Meadows Martineau – uncle of Harriet Martineau [7] – who worshipped in the Octagon Chapel in Colegate.

In 1756, local architect Thomas Ivory designed the Octagon Chapel, one of the first Methodist chapels in the world [7].

In 1784 Philip Martineau proposed the founding of a subscription library, possibly in reaction to the increasing Anglicanism of the City Library over the preceding century. This was a new departure with only five clergymen on a committee of 24, and of the 140 original subscribers 26% were women [1]. Subscribers had the keys to the Old City Library and the two libraries soon merged. Despite being supported by private subscription the new institution was rather confusingly named the Norwich Public Library [1] (claims to represent ‘Norwich’ or the ‘Public’ in the subsequent offshoots make the head spin). In 1794 the expanding library moved 150 metres to the disused Catholic Chapel of the Duke of Norfolk on St Andrew’s Street where it remained until replaced in 1835 by the building below [8, 9].

![St Andrew St 11 Public Assistance Office [1121] 1936-07-13.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/st-andrew-st-11-public-assistance-office-1121-1936-07-13.jpg?w=529)

The Norwich Public Library on St Andrew’s Street. Photo 1936 ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

Some years before the move there had been complaints about the running of Norwich Public Library (e.g., absence of standard works, lack of new titles, failure to raise the annual subscription, and a librarian with a disobliging manner) and in 1822 a break-away faction suggested setting up their own library. The Norfolk and Norwich Literary Institution – of which William Unthank was a shareholder – opened at Haymarket Hill on New Year’s Day 1823 [1, 8, 9, 10]. These two subscription libraries were to run in parallel for over half a century.

![Plunkett Haymarket Picture House latterly Gaumont [4505] 1959-07-26.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/plunkett-haymarket-picture-house-latterly-gaumont-4505-1959-07-26.jpg?w=529)

Hay Hill 1959. The N&N Literary Institution once occupied the site on which the Haymarket Picture House (latterly Gaumont Cinema) stood from 1911 to 1958. (Marks and Spencer can be glimpsed at the end of the street). ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

In the meantime, in 1838, the Literary Institution’s former partner, the Norwich Public Library, moved to new premises on the site of the old city gaol on Guildhall Hill [9]. The building is now occupied by The Library Restaurant.

![Guildhall Hill Subscription Library [4368] 1955-08-24.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/guildhall-hill-subscription-library-4368-1955-08-24.jpg?w=635&h=958)

The Library in 1955. © georgeplunkett.co.uk.

The Library set back amongst fashionable shops on Guildhall Hill. Courtesy Picture Norfolk. www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

For a time this Public Library had custody of books from the old City Library but they were poorly kept and the council threatened to move them to the rival Literary Institution [1]. The problem was eventually solved when a third library – and this time a truly public, non-subscription library – was built in 1857. The 1850 Libraries Act allowed larger boroughs to add up to half a penny in the pound to the rates to pay for library facilities and staff. Norwich Council was first to adopt the Act, Winchester was first to form a library under the Act but Norwich was first to construct its own Free Library. This opened in 1857 at the corner of St Andrew’s (Broad) Street and Duke Street [8, 9, 10]. The Act did not allow for the purchase of books so the volumes inherited from the old City Library were to provide an important nucleus for the embryonic library.

The new Free Public Library (1857) built under the 1850 Libraries Act. The smaller building in its shadows was erected (1835) on the site of the Duke of Norfolk’s Catholic Chapel and housed the ‘Martineau’ Norwich Public Library. To increase confusion the latter rented rooms in the new Free Public Library. Courtesy Picture Norfolk. www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

George Plunkett’s archive of C20th photographs shows the Public Library in 1955 [12], the name ‘Free’ having been changed by the council in 1911.

![St Andrew St Free Library [4366] 1955-08-24.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/st-andrew-st-free-library-4366-1955-08-24.jpg?w=529)

The Public Library at the Duke Street/St Andrew’s Street junction (1955). © georgeplunkett.co.uk

Towards the end of its life, the Free/Public Library was used as a shoe factory and in 1963 it was demolished to give way to the new Central Library in Bethel Street. Demolition allowed the widening of St Andrew’s Street and the corner site is currently occupied by a British Telecom telephone exchange.

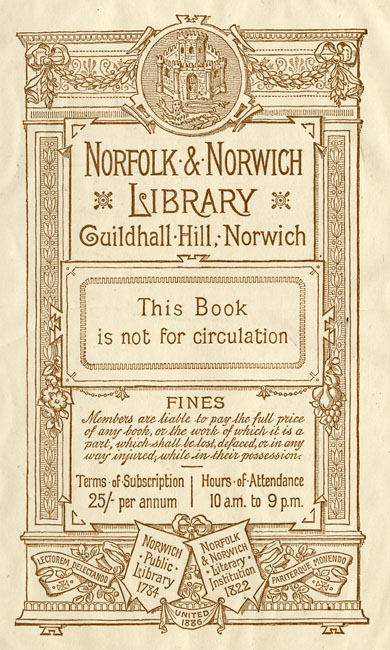

And what of the two subscription libraries? The bookplate below records that the libraries that had uncoupled in 1822 decided to come together again. In 1886 the Norfolk and Norwich Literary Institution joined the ‘Martineau’ Norwich Public Library at their site on Guildhall Hill to form the Norfolk and Norwich Library.

Bookplate. Courtesy of Picture Norfolk. http://www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

Twelve years after this merger a fire started in the premises of Daniel Hurn, ropemaker, on nearby Dove Street [13]. The blaze spread to the warehouse of Chamberlin and Sons’ department store on Guildhall Hill and gutted the adjacent library. Most of the library’s 60, 000 volumes were destroyed, including collections held by law, naturalist and archaeological societies. The restored library was reopened in 1914 and closed in 1976, when many of its books were given to Norwich School.

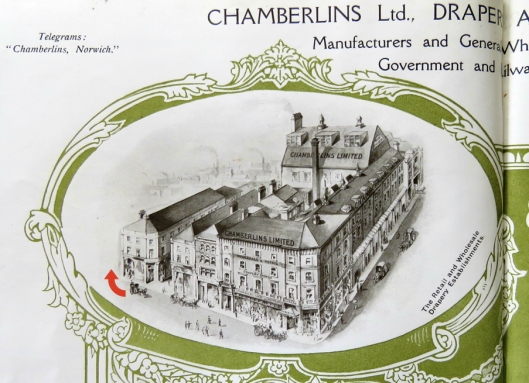

Chamberlins department store on Guildhall Hill, facing the market. The building far left is now a Tesco Metro and further left (arrow) is the recessed entrance to the N&N Library (not shown) gutted in the 1898 blaze. Image ca 1910 [14].

Fire also plays a part in the continuing story of the City Library. The Free/ Public Library built by the council at the corner of Duke/Exchange Street in the mid C19 was demolished in 1963 when the new Central Library – designed by City Architect David Percival – was opened on a site between City Hall and the Theatre Royal.

Norwich Central Library, Bethel Street. Photo George Swain. Courtesy of Picture Norfolk www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

The Central Library was destroyed by fire in August 1994, much as the subscription library on Guildhall Hill had been destroyed nearly a hundred years before. Over 150, 000 books were burned along with irreplaceable historical documents from the Record Office.

The 1994 library fire. © ITV News Anglia

In 2001 The Forum, designed by Michael Hopkins and Partners, arose from the site of the damaged library, facing St Peter Mancroft. The Norfolk and Norwich Millennium Library, which is housed in The Forum, has been cited as the busiest library in the UK [15].

The city’s first branch library, the Lazar House in Sprowston, was in a Norman chapel and leper hospital founded by the first Bishop of Norwich, Herbert de Losinga (d 1119) [16]. After local antiquarian Walter Rye had rescued the building from destruction in the early C20 it was presented to the city by Sir Eustace Gurney and served as a branch library from 1923 to 2003 [17].

The C12 Lazar House, off Sprowston Road

Earlham Branch Library (1929), one of the 47 local libraries in Norfolk … another opportunity to show its fine calligraphy.

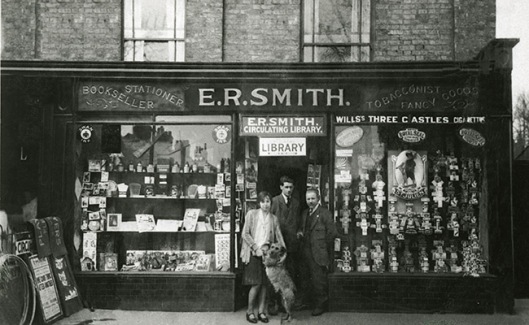

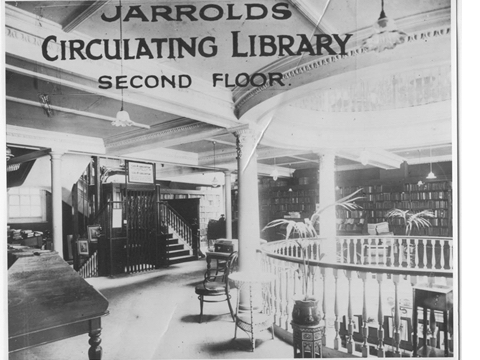

In addition to subscription libraries and public free libraries readers could, for a small fee, rent popular books from commercial circulating libraries. WH Smith and Boots the Chemist had hundreds, Harrods of Knightsbridge had one, Jarrolds of Norwich* had one – even Edmund Smith’s stationery and tobacconist shop on Unthank Road housed a circulating library.

ER Smith’s circulating library at 139 Unthank Road ca 1931. Now PW Sears’ newsagents. Courtesy Picture Norfolk www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

Bonus track*

After posting this article, Caroline Jarrold kindly sent this image of the circulating library on the second floor of Jarrolds Department Store.

Courtesy Caroline Jarrold

© 2018 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- Kelly, Thomas (1969). Norwich, Pioneer of Public Libraries. Norfolk Archaeology vol xxxiv pp 215-222.

- Wilkins-Jones, Clive (ed). (2008). Norwich City Library 1608-1737. Pub: Norfolk Record Society.

- Beck, A.J. (1986). Norwich Cathedral Library: its foundation, destructions and recoveries. Pub: Dean and Chapter of Norwich 1986.

- Ker, N.R. (ed) (1964). Medieval Libraries of Great Britain: A List of Surviving books. Pub: Offices of the Royal Historical Society.

- http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk/monuments/John%20Pettus/John_Pettus.shtm

- Wilson, Kathleen (1995). The sense of the people: politics, culture and imperialism in England, 1715-1785. Pub: Cambridge University Press.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/03/15/three-norwich-women/

- Nowell, Charles (1920). The Libraries of Norwich. Pub: The Library Association.

- Loveday, Michael (2011). Norwich Knowledge: An A-Z of Norwich – The Superlative City. Pub: Michael Loveday. ISBN 9780957088306.

- Fawcett, Trevor (1967). The Founding of the Norfolk and Norwich Literary Institution. Library History vol 1, pp 46-53.

- https://content.historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/iha-english-public-library-1850-1939/heag135-the-english-public-library-1850-1939-iha.pdf/

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/sta.htm#Stand

- Mackie, Charles (1901). Norfolk Annals vol 2. See: http://www.hellenicaworld.com/UK/Literature/CharlesMackie/en/NorfolkAnnals2.html

- Citizens of No Mean City (1910). Pub: Jarrold and Sons, London and Norwich.

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/290530/busiest-libraries-in-the-uk-united-kingdom/

- http://www.sprowstonheritage.org.uk/Lazar_House

- Hepworth, Philip and Alexander, Mary (1965). Norwich Public Libraries. Pub: Norwich Libraries Committee.

Thanks. I am grateful to Gudrun Warren, Librarian and Curator, Norwich Cathedral for her kind assistance. Thanks also to Clare Everitt for permission to use images from Picture Norfolk that, along with the Plunkett archive, provides a superb record of Norwich and Norfolk life.

[cid:image001.png@01D404AA.1E15BEC0]

Hello Reggie

I thought that you might like this image for your collection from our archives.

Interesting article!

Best wishes

Caroline

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Caroline. The image is fascinating, not only to get a sense of the size of the library but to see the atrium/light well formerly in the centre of the store. I shall post it on the blog. Reggie

LikeLike

So very close to my heart – and to my house in the case of Earlham Library! Thank you for this one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know you are fond of the library. How nice to have it so close. It’s an active library – we went to a talk there on Norwich Gates only last week.

LikeLike

Always fascinating and well researched. Thanks Colonel

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Theo.

LikeLike

Full of fascinating information as always, Reggie – thank-you! I can well imagine that the library in the Forum is the busiest in the UK – it can get quite noisy at times!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s certainly different from the hushed atmosphere of the library I grew up with. Still, it’s great to see so many activities going on and that’s perhaps that’s why it’s so successful, don’t you think?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, definitely!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another excellent post. I well remember the old Central Library in St Andrews (and the County Library on Thorpe Road). As a child I lived in Hellesdon, outside the City, so had to have an uncle who lived in Norwich act as guarantor before I could join the City library – the Aylsham Road branch.

I thought the figures of the man with a sword and the dragon on the Ethelbert gate were St George & his opponent

Don Watson

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Don, I’m delighted to hear that you can remember the Central Library in St Andrew’s; I can recall the ‘1963’ library before it burnt down.

I had intended to include a photograph of the Aylsham Rd branch Library (1931), which is so similar to the one at Earlham. The ‘St George’ and Dragon in the spandrels of the Ethelbert Gate of the cathedral are C19 and C20 restorations but I suppose them to be based on the original medieval carving. A wild man/angel/St George fighting a dragon appears to be common on gatehouses, illustrating the gate’s function of keeping out malign influences. Since the citizens who torched the cathedral in the C13 were forced to rebuild the Ethelbert Gate I can’t help thinking it also represents a sly dig against the rioters.

LikeLike

Another interesting read. I used the library a lot in the late seventies and also remember St Andrew’s Hall at that time as a music venue

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Pat, Like you I visit StAndrew’s Hall for music. We were recently there for concerts in the Norfolk and Norwich Festival. What a shame that a new concert hall couldn’t have been accommodated in the Anglia Square redevelopment. Reggie

LikeLike

Having looked again at the interesting illustrations to this post I have to say that Chamberlins store occupied almost the whole of the block from Dove Street to the Subscription Library and along Dove Street to Pottergate. The wide street (with artistic licence0 in the picture is Dove Street so the entrance to the Tesco Metro is on the front corner and the entrance to the Library is visible to the left. Can I suggest that there might be an interesting subject in the gone ( but not forgotten) stores of Norwich – Chamberlins Garlands, Buntings, Woolworth’s (the rebuilt store is the part of M & S in your picture of the old Haymarket cinema), Greens, Rumsey Wells etc.

Don Watson

.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An article on the old stores of Norwich would be a good idea, Don. I do vaguely remember Woolworth’s being taken over by M&S in the late 1980s.

LikeLike

Another great article, and very close to my heart as a librarian. Just to mention that Denys Lasdun’s Library at UEA will be 50 years old later this year (although the collection occupied spaces in Earlham Hall and the UEA Village before that). One of the UEA collections I look after is the literature collection and I’ve been surprised just how many 18th and 19th century volumes we have sitting on the shelves of a library that’s so young. The official history of UEA explains this: “Of particular importance was the agreement, 1966-67 with the Norfolk and Norwich Library to purchase books from this splendid nineteenth century subscription library. When their lease finished in 1973, UEA would take over most of their stock.” (Sanderson, History of the University of East Anglia, 2002). So while Norwich School might have benefited from some of its volumes, I think the Norfolk and Norwich’s main inheritor was the university. If any readers have access to UEA Library then go up to floors 2 or 3 and look for some fine leather bindings. If you open them up you are likely to find some of the Norfolk and Norwich book plates illustrated above.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Grant, Thank you for letting us know that some of the old N&N Library’s books ended up at the UEA. The references I came across said that ‘most’ or ‘the majority’ went to Norwich School so evidently some escaped. It’s a long time since I used the UEA Library and my ticket is lapsed; can members of the public gain access to see the Norwich books? Kind regards, Reggie

LikeLike

Hi Reggie. Anyone can sign up for a day pass (no charge) if they bring in photo ID and fill in a form. Details here: https://portal.uea.ac.uk/web/hub/library/access/visitors . I don’t think it’s a problem taking out day passes in an ad hoc fashion, but for £20 a Norwich resident could gain reference only access for a whole year. As well as the books there are wonderful views to be had from the third floor. I just had a look at the catalogue to see if there’s some way to pull out the N&N volumes, but they’re not tagged. However I’ve seen hundreds on the shelves – saw several today. The UEA Library was also given some books from Blickling Hall, but I think most of these have now been returned to the National Trust. Interestingly, some of those responsible for founding UEA were associated with Cambridge and tried to arrange for Cambridge University Library to ship across some of its books to give the new University a kick-start. THis was seriously considered and debated but the fear was that Cambridge University Library’s legal deposit status might be under threat if it loaned a large number of books off site. If you or regular Colonel Unthank readers do want to make a visit to the UEA Library then drop me a note – if I’m free I’ll give you a quick orientation to the building and its contents. Grant

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this Grant

LikeLike

Fascinating and so rich in delightful details, as always.

We had W.H. Smith bookstores here in Toronto when I was a kid. They were a great favourite of mine.

But, gah! To think of all fire has taken.

LikeLike

… then in 1995 our Georgian Assembly House caught fire. I haven’t been to Canada for some years but thought, then, that it was a selective fusion of American and British influences. The WH Smith bookstores seal it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The absent Dukes of Norfolk | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Norwich: shaped by fire | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Noël Spencer’s Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH