The leg-of-mutton shape of ancient Norwich is defined by the city walls and by the River Wensum that runs across the city, providing a natural barrier on its eastern flank. To walk along the river is to retrace the fortunes of the city’s industrial past. I did this in two unequal stages, the first from New Mills to St James’ Mill.

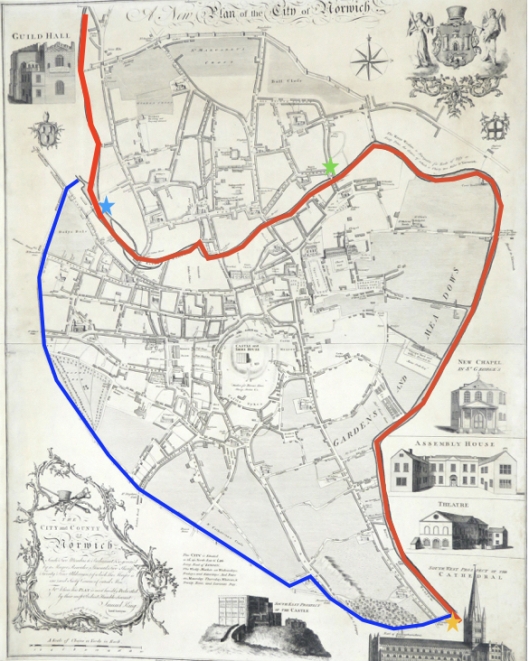

The city walls are in blue, the river Wensum in red. I walked Part 1 from New Mills (blue star) to Whitefriars’ Bridge (green star). Plan of Norwich 1776 by Daniel King. Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service NWHCM: 1997.550.81:M.

I started at the head of navigation by turning into New Mills Yard off Westwick Street. The water gauge in the colour photograph shows how the tidal waters have inundated the city over the years.

Norwich flood levels 1570-1912. Right, Jonthan Plunkett in 1961 standing next to cast and carved flood level gauges (Courtesy www.georgeplunkett.co.uk)

The current building, erected 1897, straddles the river between the tidal waters to the east and the river to the west where the level is maintained by sluice gates.

The Compression House at New Mills, built by the council in 1897 to pump sewage to Trowse.

During the Industrial Revolution the Norwich textile industry was outpaced by mills in the North of England that had better access to coal and fast-flowing water for running the new steam-powered looms. However, there was a sufficient head of water at New Mills to drive the compressed air system from 1897 to 1972, pumping sewage down to Trowse [1,2]; it also powered machinery in the Norwich Technical Institute (now Norwich University of the Arts) a few hundred yards downstream.

This pneumatic excursion replaced the original New Mills, built in 1710 for grinding corn and supplying the city with water. In turn, New Mills had replaced an older mill of 1410 [1].

New Mills in 1880 by A. Coldham. Courtesy Norfolk County Council

Continuing clockwise on the north bank of the river the next bridge, decorated with the City of Norwich coat of arms and dated 1804, is St Miles’ or Coslany Bridge [2]. It is the city’s first iron bridge built 25 years after the world’s first major iron bridge at Ironbridge, Shropshire.

Coslany Bridge designed by James Frost. The cast iron sign to the far right marks the water level in August 1912.

St Miles Bridge in the 1912 flood …

Courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

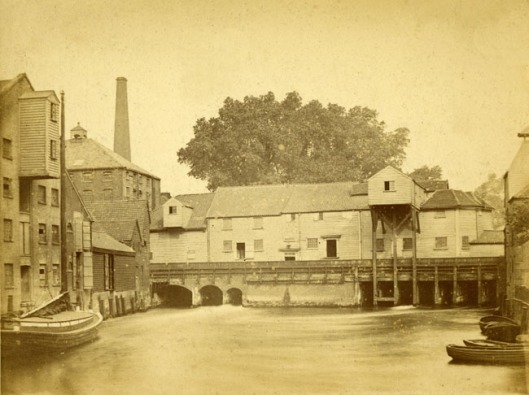

Standing on St Miles’ Bridge connects you with three of the industries that formerly sustained this city (while polluting its river). First, on the north bank, the present-day public housing in Barnard’s Yard is named for the Norfolk Iron Works of Barnard Bishop and Barnards [see 3 for a fuller story]. On the south side is Anchor Quay, now private housing, but once the home of Bullard and Sons’ Brewery that supplied the city’s countless drinkers (‘one pub for every day of the year‘) [see 4].

The courtyard of the Anchor Quay Brewery in 1912. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

The Bullards sign can be glimpsed on the Westwick Street wall across the river

And third, the rose madder colour of the Anchor Quay development is a reminder of the dyeing industry that grew, hand in glove, with the city’s textile industry. The Maddermarket – where dye from dried madder roots was sold – was just a few hundred yards to the south (see [5] for a fascinating article on making madder dye).

Continuing along the north side of the river we can see across to the site of the old Duke’s Palace Ironworks off Duke Street, which was replaced in 1892 by the Norwich Electric Light Company whose buildings were designed by Edward Boardman and his son Edward Thomas Boardman. At one time, the river would have provided water for the steam engines but after the Thorpe Power Station was opened in 1920s the Duke Street site was used for offices and storage [6].

Looking downriver from the St Miles’/Coslany Bridge, past the rose madder houses of Anchor Quay, we see the curved building containing the derelict offices of Eastern Electricity.

Sandwiched between the former brewery and the five-storeyed offices of the Norwich Corporation Electricity Department is a smaller building owned by the electricity board. In 2006, as part of the Eastinternational exhibition, artist Rory Macbeth used this as a canvas on which to paint the entire 40,000 words of Thomas More’s Utopia [7]. Due to be demolished in 2007, the structure still stands.

In 2006, another exhibition played imaginatively with the derelict riverside buildings. In the windows of the adjacent, curved office building a group of artists placed red film over the windows plus lettering that read: norwich red/water of the wensum/tin mordant/madder. This formulation for colouring fabric, reflected in the water, created the illusion that – once more – dyeing ‘made the river run red’ [8]. The reason for the red river comes a little downstream, for the story follows the course of the river.

©Presence

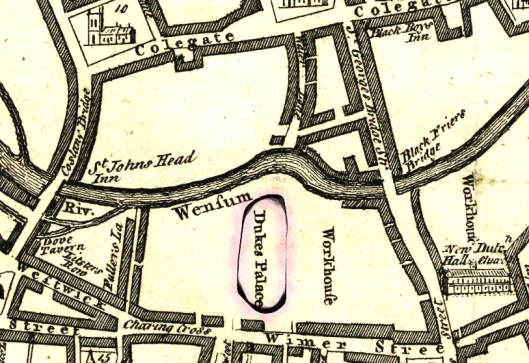

This stretch of the river forms the river frontage of what was once the Duke of Norfolk’s palace.

According to Samuel King’s 1766 map the Duke’s Palace (circled) on the south bank once occupied most of a block between Coslany Bridge (modern day Anchor Quay) and St George’s Bridge Street (St Andrew’s and Blackfriars’ Hall, named here New Hall and Dutch Church). Courtesy of the Norfolk Museums Service NWHCM: 1997.550.81:M.

The Dukes of Norfolk built two palaces on the site, in 1561 and 1672, but proximity to the river caused problems. According to Thomas Baskerville in 1681:

“In this passage where the city encloses both sides of the river, we roved under five or six bridges, and then landed at the Duke of Norfolk’s Palace, a sumptuous new-built house not yet finished within but seated in a dung-hole place, though it has cost the Duke already 30 thousand pounds in building, as the gentleman as shewed it told us, for it hath but little room for gardens, and is pent up on all sides both on this and the other side of the river, with tradesmen’s and dyers’ houses, who foul the water by their constant washing and cleaning their cloth, whereas had it been built adjoining to the afor said garden it had stood in a delicate place.” (Quoted in [9]).

Proximity to the water meant that the cellars were always wet, which affected the foundations [10]. The fate of the palace was sealed when the Mayor of Norwich, Thomas Havers, refused the duke permission to process into the city with his Company of Comedians: in 1711 the duke ordered the palace be pulled down [9, 10]. When the duke vacated his palace there was no road through his estate and across the Wensum as there is today. The present – but not the first – bridge to bisect the ducal waterfront was built when Duke Street was widened in 1972 to take traffic out of the city onto the inner ring road [2].

Duke’s Palace Bridge 1972. Regrettably, there is no continuous river walk around the city, either because developers have been allowed to build up to the river’s edge or, where there is a walkway, it is generally not possible to walk under the bridge, as here.

This utilitarian bridge of 1972 replaced the first and much more elegant cast-iron bridge of 1822, which would be lost were it not for the Norwich Society who bought and stored the bridge until it could be re-used at the entrance to the Castle Mall car park [11].

The old Duke’s Palace Bridge (1822-1972) now at Castle Mall

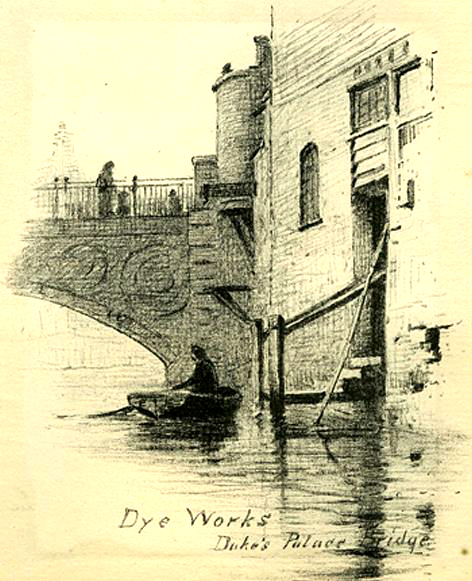

Near the original site of this bridge we come to the dyeworks run by Michael Stark in the early C19, drawn below by his son James – the Norwich School artist. Stark Senior developed a way of staining the silk warp the exact same shade of red as the wool or worsted weft. This involved madder, a tin mordant and the fortuitously chalky waters of the Wensum, yielding a deep, true scarlet [12]. It seems safe to assume that it was the emptying of Stark’s dye vats that made the river run red.

Michael Stark’s dyeworks adjacent to the Duke’s Palace Bridge. By James Stark 1887 [from 13]

I managed to preview the next bridge by walking along a gangway on a building at the rear of the Duke Street Car Park. St George’s/Blackfriars’ Bridge was built of Portland stone by Sir John Soane (1783-4) before he became Surveyor of the Bank of England [2].

Soane’s bridge meets the south bank between the grey-painted Gunton and Havers building (1914) and the red brick Norwich Technical Institute (1899) – both now part of Norwich University of the Arts.

There is, however, no direct route for the riverside walker who must take a detour left down Duke Street, right along Colegate then right again onto St George’s Street before meeting the bridge. This diversion takes you past Howlett and White’s Norvic shoe factory built by Edward Boardman in 1876 and 1895. Around the end of the C19 it was the largest shoe factory in the country, employing a fraction of the outworkers employed in the textile trade a century before [2].

St George’s Bridge from the south bank …

To the left, the former Gunton and Havers builders’ merchant (Havers is a relative of actor Nigel Havers); to the right, the stone portico of the former Norwich Technical Institute (1899). Both are now part of Norwich University of the Arts. Damien Hirst’s flayed and dissected man gives an unconscious nod to Norwich Red.

I continued via the north bank to Fye Bridge, its name perhaps derived from ‘fye‘, to clean the river [10]. The first recorded bridge-proper dates from 1153 but excavations in 1896 indicate this was predated by a wooden walkway that connected the south side to the Anglo-Scandinavian settlement in Norwich-over-the-Water [14]. The present bridge, whose double arches are based on downstream Bishop Bridge, was built in 1933. Just before the bridge is the residential development of Friars Quay, built on Jewson’s Victorian timber yard [15]. This 1970s housing has assimilated well despite Pevsner and Wilson’s deathless judgement, “It falls only just short of being memorable” [2].

Fye Bridge from the west with Anchor Quay housing just visible to the left

Crossing Fye Bridge then looking back from Quayside on the south bank this photograph shows the reconstruction of the bridge in 1931. Allen & Page animal feed mill (now houses) can be seen on the left and ‘Jewson’ marks their timber yard beyond the bridge.

![1931-08 Reconstruction crane at Quayside [B075] 1931-08-03.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/1931-08-reconstruction-crane-at-quayside-b075-1931-08-03.jpg?w=529)

Reconstruction of Fye Bridge 1931. ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

Continuing eastward on the south bank: There was a wooden bridge at Whitefriars as far back as 1106 but what was known as St Martin’s Bridge was destroyed by the Earl of Warwick when he tried to deny Kett’s rebels access to the city in 1549. In 1591 this was replaced by a stone bridge that limped on until the City Engineer constructed the present Whitefriars Bridge (1924/5) [14].

Old Whitefriars’ Bridge 1924, before its replacement. Courtesy Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

Adjacent to the bridge is St James Mill, built by the Norwich Yarn Company (1836-9) in an attempt to revive the city’s textile industry. Ian Nairn – the acerbic architectural commentator – thought this ‘the noblest of all English Industrial Revolution Mills’ [2]. Until a few years ago the mill housed Jarrold’s Printing Works; the John Jarrold Printing Museum is in an adjacent building.

Willett & Nephew had 50 power looms on the third floor of the mill and are believed to have produced the shawl below. Members of the Yarn Company could now produce the famous ‘Norwich Red’ shawls on their power looms but, by the time the Company had begun production in 1839, factories in Yorkshire and Paisley were already mass-producing shawls in large factories, contributing to the market’s slow decline.

A Norwich Red Shawl courtesy of Joy Evitt

© 2018 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/mid.htm#Newmi

- Pevsner, Nikolaus and Wilson, Bill (1962). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/06/15/barnard-bishop-and-barnards/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/09/15/bullards-brewery/

- http://www.naturesrainbow.co.uk/category/madder/

- http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?MNF61834-Duke%27s-Palace-Ironworks-and-Norwich-Electric-Lighting-Company&Index=53786&RecordCount=56542&SessionID=071f84aa-3266-4621-85cc-d97a40c30c46

- http://www.racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp?action=getsurvey&id=208

- http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?TNF1512-Norwich-Duke-Street-Dyeworks—Presence-(Archaeology-and-Art)

- http://hbsmrgateway2.esdm.co.uk/norfolk/DataFiles/Docs/AssocDoc6824.pdf

- Meeres, Frank. (2011). The Story of Norwich. Pub: Phillimore & Co.

- http://www.broadlandmemories.co.uk/riverwensumbridges.html

- http://www.tartansauthority.com/research/sources/willet-nephew-and-co/

- http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?TNF1521-Norwich-Duke%27s-Palace-Bridge—James-Stark-(Archaeology-and-Art)

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/riverbridges.htm and for the reconstruction of this bridge see http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/fyebridgerebuilding.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friars_Quay_(Norwich)

Thanks: to Joy Evitt and Jenny Daniels for background on Norwich shawls; to Clare Everitt for permission to use the Picture Norfolk images; to Paris Agar of Norwich Castle Museum for access to the maps; and to the Plunkett archive for their images.

O what a pleasure – these get better and better!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your kind comments are especially welcome Heather. Overnight a longer post was somehow lost and I spent a frantic morning rescuing what was left. On the positive side … it was good to be able to concentrate on the Norwich Red and the dyeing industry instead of diluting it with the heavy industry around the river bend!

LikeLike

Fascinating. Thank you so much. I had been intrigued by the writing on the (what I now know to be) Electricity building which is on the edge of a private car park off Westwick Street. Now I know it’s Utopia.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Jeremy, it’s pleasing to see Utopia’s still here.

LikeLike

As always a great excursion through the history of our city. I liked the picture of St Miles bridge in the 1912 flood. My grandfather told the story of crossing the bridge in St George’s in a cart as the wood blocks forming the road surface floated away ( and kept many people warm that winter). Magdalen Street from Fye Bridge to Stump Cross was still surfaced with wood blocks in the 1950’s.

Don Watson

LikeLiked by 1 person

I couldn’t resist that image of a man standing above the Wensum in full spate. Was it the flood of 1912 that your grandfather experienced? I had heard of wooden blocks being used as a road surface (for quietness?) but didn’t appreciate they were still being used in the 50s. Thank you for the fascinating insights, Don

LikeLike

Another fascinating post.I always look forward to these. You must put so much work into your research.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do enjoy research and fortunately we have such a rich history to dig into. Thank you Liz.

LikeLike

It was indeed the 1912 flood. Wood blocks were an ‘interesting’ surface if you were a cyclist. In weather like the current heatwave they shrank and rattled as you went over them then when it rained they were really slippery – fortunately traffic was much less in those days and you could pick yourself up with little damage

Don Watson

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always learn so much from your wonderful posts, Reggie. I had always wondered why the entrance to Castle Mall carpark looked like a bridge! I look forward to the rest of the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A delightful post, as always, Reggie. And oh, how I envy you that lovely walk along the river.

LikeLike

We don’t make enough of our riverside. Pity, it could make a wonderful historic walk for visitors. We could do with some tips from Toronto, Katherine.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Norwich Way of Death | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The absent Dukes of Norfolk | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Going Dutch: The Norwich Strangers | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The Plains of Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

A really enjoyable read. Thank you

LikeLike

Thank you for the kind words, Christopher

LikeLike

I know this is a few years old now but I wondered if you could answer a question I have about one of Norwich’s bridges – St George’s Street to be precise?

There is a small hole and ‘slide’ that is in the Playhouse side of the bridge and I can’t figure out what it might have been for, nor can I find any reference to it in any literature regarding Norwich’s history or the bridge. Do you know what I am referring to and what it would have been used for please?

LikeLike

Vanessa Trevelyan of the Norwich Society informs me that the ‘slide’ allows the hoses for fire engines and road steam engines to get water from the river without snagging. All the metal bridges in Norwich have them.

LikeLike

Ahh, thank you for answering my question! That’s a really interesting feature that you know I’m going to be looking for on every metal bridge I cross for the rest of my life now!! I wonder how many other cities bridges have this feature or similar..?

LikeLike