In this second part of the river walk we turn 1800 around Cow Tower at the edge of deceptively tranquil meadowland before descending into Victorian industry south of Station Bridge.

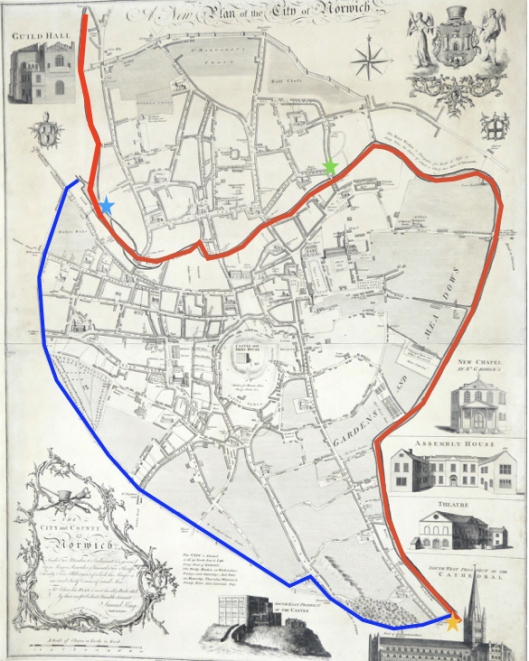

Continuing the river walk, I travelled from Whitefriars’ Bridge (green star) to Carrow Bridge (yellow star). Plan of Norwich 1776 by Daniel King. Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service NWHCM: 1996.550.81.M

Downstream from Whitefriars’ Bridge and the former home of Jarrolds Printing Works, the John Jarrold Bridge (2011) connects the cathedral precinct (and the Adam and Eve pub) with the St James Place Business Quarter and to Mousehold Heath beyond. The curving box girder, clad in weathered steel with a hardwood deck, seems the most welcoming of the later bridges.

On the south bank, not far from this bridge, you will walk over a sluice that connects the river with the country’s last surviving swan pit where the Master of the Great Hospital fattened cygnets for feasts. This pit, in the grounds of the Great Hospital, was built in the late C18 by William, son of Thomas Ivory who designed the Octagon Chapel and Assembly Rooms [1].

Half-hidden, a swan-shaped sign marking the sluice to the Swan Pit in the Great Hospital

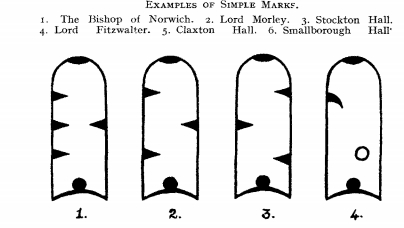

The Bishop of Norwich also owned swans [2] but whether he feasted on them is not recorded.

The Bishop of Norwich marked the beaks of his swans with four nicks. ©[15]

Fifty-foot-high Cow Tower (rebuilt late C14) was strategically placed to fire upon the higher ground across the river. It is an early example of Norwich brickwork into which, for nine shillings each, stonemason Snape inserted cross-loops that could have accommodated longbows, crossbows and hand-held artillery [3]. Still, this didn’t deter Robert Kett’s rebels – during their righteous uprising against land enclosures – from firing down from Mousehold Heath and damaging the battlements.

Tapered embrasures allowed a wide range of fire

Next, Bishop Bridge – the only surviving medieval bridge (c 1340) [3]. From here you would have seen followers of John Wycliffe (d.1384) and later heretics burned just over the bridge in Lollards’ Pit. And in 1549, from what we now know as Kett’s Heights, you would have seen Robert Kett’s followers fire down upon, then storm, the fortified bridge.

On the opposite side of the bridge, to the right of the Lollards’ Pit pub, is the superstructure that guided the rise and fall of the Gas Hill gasometer. Built in 1880, at the foot of the steepest hill in Norfolk, it stored town gas released by burning coal. But coal became increasingly redundant from the late 1960s when domestic appliances were adapted to use natural gas from under the North Sea.

Downstream, a ferry once ran across to the cathedral watergate. In 1807, Cole referred to it on his Norwich plan as Sandling’s Ferry (after its C17 operator) although by then the ferry was being run by John Pull (active 1796 to 1841) [4]. Evidently, he managed to make a living despite the proximity of toll-free Bishop Bridge.

The Sandling Ferry on the 1807 Plan of Norwich by G Cole. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collection NWHCM: 1954.138.Todd5.Norwich.19

Every piece of Norman sandstone for the building of Norwich Cathedral (from 1096) would have come across the Channel and up the Wensum to the mason’s yard via a canal that remained open until c.1780.

Pull’s Ferry. C15 watergate and C17 ferry house, restored in 1948/9 by Cecil Upcher [3]

In 1811 a toll bridge was built across the Wensum near the present day Thorpe Rail Station, taking its name from the iron foundry on the city-side bank.

Foundry Bridge on the 1819 Longman map, courtesy www.georgeplunkett.co.uk

In 1844, the railway arrived from Yarmouth to the east. To make that next step across the river towards the city centre a wooden bridge was replaced by this iron one seen in the painting by John Sell Cotman’s son, John Joseph.

- John Joseph Cotman’s Old Foundry Bridge. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM: 1916.41.1

The Victorian solution to encroaching modernity was to build Prince of Wales Road (1850s/1860s) on rubble from the old city wall at Chapelfield [5]. This provided a wide direct route, connecting the station to the city centre and market [3]; in 1888 Foundry Bridge/Station Bridge was made correspondingly wider.

Foundry Bridge, looking up Prince of Wales Road from the station side. Note the arrow pointing down the steps.

A diversion. Do not do as I did and follow the seductive arrow on the side of Norwich Nelson Premier Inn for it leads to a dead end, not a riverside walk. Ploughing on, I walked up Prince of Wales Road, left on Rose Lane and left on Mountergate. A sign on the side of the new Rose Lane Car Park states that this was the site of the Norwich Fish Market that moved here in 1913.

Before this, the fish market had been in the Norman marketplace for over 800 years [6]. In 1860 the shambolic stalls were replaced with a neoclassical building at the back of the present-day market but this was demolished in 1938 [7].

The Old Fish Market (1860-1938) on St Peter’s Street, roughly where the Memorial Gardens are today. Top left, the battlements of the medieval Guildhall grin through the mist. Courtesy Norfolk County Council, Picture Norfolk

On the opposite side of Mountergate is an old weavers’ building with one of the last remaining weavers’ or through-light windows.

As Mountergate constricts to an alleyway, a tall wall screening Parmentergate Court is all that remains of the once-thriving Co-op Shoe Factory that had, itself, moved into premises vacated by Boulton and Paul.

The real object of my diversion was to check on the progress of the restoration of Howard House, derelict so long its scaffolding is said to have gained listed status. Now, Orbit Homes are restoring the house as part of the residential St Anne’s Quarter.

Howard House was built in 1660 by Henry Howard 6th Duke of Norfolk on land seized by Henry VIII from the Austin Friars [3]. The duke laid out a pleasure garden that was still referred to on C19 maps as ‘My Lords Gardens’. The garden wall peeping over the hoarding on King Street is probably the original boundary wall of the friary [8].

Instead of continuing down King Street, which I’ll save for another day, I retraced my steps, crossed Foundry Bridge and walked along the station side of the river. On the east bank the contrast between now and then couldn’t be more stark: modern leisure vs Victorian industry. From 1999 the Riverside leisure complex (gym, cinema, bowling, pub, restaurants) replaced the engineering works of Boulton and Paul, which moved here from the other side of the river during the First World War [9].

Boulton and Paul’s Riverside Works 1939, just before it was bombed in the Blitz. The stadium of Norwich City FC can be seen to the right. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council, Picture Norfolk.

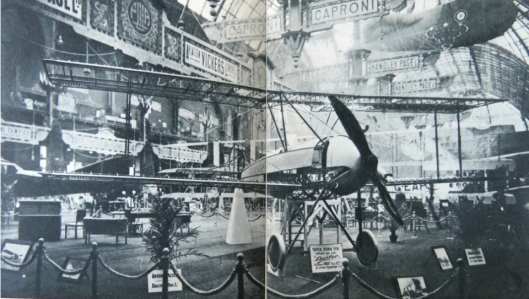

Like their great rivals Barnard Bishop and Barnards, several bridges upstream, Boulton and Paul produced wire netting amongst an enormous range of products for farm, estate and garden. During World War I they were asked by the government to produce aeroplanes, making more Sopwith Camels than any other company.

After WWI they were to produce light bombers to their own design, including the Norfolk-named Sidestrand and Overstrand. B&P also produced the ‘Daffy’ Defiant night fighter as well as a night-fighter named after that well-camouflaged bird of the Norfolk Broads – the Bittern [9].

Boulton and Paul exhibited the world’s first all-metal plane, the P10, in Paris 1919. ©Boulton and Paul. From [9].

Looking across the river is the newly-coined St Anne’s Quarter – a seething building site whose name is explained on the 1884 OS map. Not only does it lie upon C17 ducal gardens but on the St Ann’s Ironworks (1847-1883) belonging to Thomas Smithdale & Son [10]. St Ann’s Works, where the Smithdales cast the iron required for their business as millwrights, was named for St Ann’s Chapel once on this site. The former foundry is now part of a larger site comprised of the Old Norwich Brewery on King Street, several maltings and the only-named Synagogue Street in the country (bombed in WWII).

St Ann’s Foundry, opposite the Riverside complex. The zoomable 1884 OS map is courtesy of Frances and Michael Holmes [11].

Connecting the two sides of the river is the Lady Julian Bridge (2009) that commemorates Julian of Norwich, the anchoress (c1342-c1416) whose Revelations of Divine Love is said to be the first English book written by a woman [12]. If you were to cross her bridge, turn left on King Street then right on St Julian’s Alley you would come to her eponymous Anglo-Norman church and her cell, largely rebuilt after the Blitz.

Along this stretch of the river is a building that georgeplunkett.co.uk lists as an old grain warehouse. The ownership is unclear but whoever owns the corrugated building occupies one of the last undeveloped sites on the river margin.

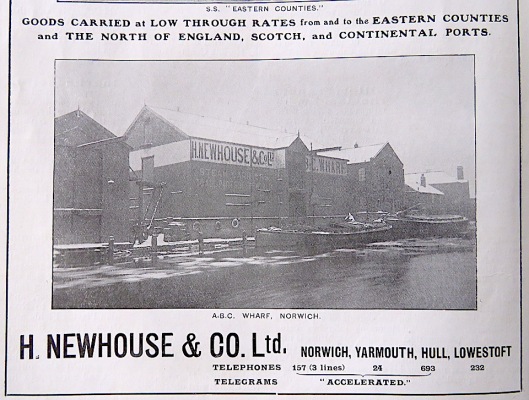

[Updated March 3 2019. Reading ref 15 I see this building at the A.B.C. Wharf was owned in 1910 by H Newhouse & Co Ltd whose Yarmouth – Hull steamers plied goods along the eastern seaboard.

Connecting the profusion of riverside apartments around the Old Flour Mill with the railway station is the Novi Sad Friendship Bridge, built by May Gurney (2001) to mark the twinning of Norwich with the Serbian city.

The Old Flour Mill started life in 1837 as the Albion Yarn Mill for making worsted, silk and mohair thread to be used in our weaving industry but by the time of the 1884 OS survey it had become a ‘Confectionery’. In the 1930s, the building was taken over by RJ Read of Horstead Water Mill. Latterly, known as the Read Woodrow flour mill it closed in 1993 and was converted to apartments from 2005 [13].

The redbrick buildings of the former flour mill

![King St 237 Read's flour mills across river [6597] 1990-03-18 (1).jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/king-st-237-reads-flour-mills-across-river-6597-1990-03-18-1.jpg?w=529)

King Street Flour Mill 1990. Courtesy http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk

Within living memory the Wensum would have been alive with ships, some much larger than picturesque Norfolk wherries. Below, the movable section of this bascule bridge is being raised to allow a sea-going ship through.

![Wensum Carrow bascule bridge open for ship [4765] 1964-05-09.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/wensum-carrow-bascule-bridge-open-for-ship-4765-1964-05-09.jpg?w=529)

Carrow Bridge opening for a ship in 1964. Courtesy http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk

River trade was also regulated by the paired boom towers near Carrow Bridge, part of the early C14 walled defences. A boom – originally a beam but in this case chains of Spanish iron – was strung across the river to regulate access and extract tolls [14]. The chains were raised by a windlass in the twin tower on the west/city side.

The eastern boom tower – the Devil’s Tower – downstream of Carrow Bridge

This two-part walk around the river underlines the richness of the city’s industrial past. Once, Norwich made things. Its pre-eminent textile trade survived into the C19 to be replaced by a variety of trades of the Industrial Revolution: shoe-making, iron-working, brewing, general engineering, aeronautical engineering and other light manufacturing industries. But, in the later stages of this riverside walk especially, there is now little to show of those old trades as all traces of productive industry are being erased in favour of housing and leisure. We stopped at the last road bridge, just short of Colman’s mustard factory that was synonymous with this city for a century and half. After the business closes next year the future of the site is unclear but what price riverside apartments?

©2018 Reggie Unthank

BONUS TRACKS

Wensum body loves you. Frank Sinatra

Blood Red River Blues. Josh White (to accompany the previous post on Norwich Red dye). Click: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hs2_6LRPgqo

Red River Blues. Henry Thomas (1928)

Moody River. Pat Boone

Down by the River. Neil Young

Down by the Riverside. Traditional

Time and the River. Nat King Cole

Take me to the River. Al Green

Cry me a River. Julie London

Moon River. Andy Williams

Ol’ Man River. Paul Robeson

Down to the River to Pray. Alison Krauss

Travelling Riverside Blues. Robert Johnson

River. Joni Mitchell

The River. Bruce Springsteen

Up a Lazy River. Louis Armstrong

River Deep Mountain High. Ike and Tina Turner. Not for Norfolk

Sources

- http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2418563

- Ticehurst, N.F. (1936). On Swan-Marks. British Birds vol 29, p266.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus and Wilson, Bill (1962). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pulls_Ferry,_Norwich

- Meeres, Frank (2011). The Story of Norwich. Pub: Phillimore.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norwich_Market

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/markets.htm

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/kin.htm

- The Leaf and the Tree: The Story of Boulton and Paul 1797-1947 (1947). Author: Anon. Pub: Boulton and Paul Ltd.

- http://www.norfolkmills.co.uk/Millwrights/smithdale.html

- http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk/norwich_maps/Norwich_map_1884_zoomify.htm. Do visit the Holmes’ exciting new site on Norwich history http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_of_Norwich

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5768436

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5766195

- ‘Citizens of No Mean City: Norwich – the East Anglian Capital’ (ca1910). Pub: Jarrold and Son, London & Norwich.

Thanks: Frances and Michael Holmes; Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk; and members of the Dragon Hall Local History Group (Sheila Fiddes, Richard Matthew and Barbara Roberts).

The best yet – my own home patch, and the secrets behind the places which matter most to me as one who lived in and loved King Street and cycles past Cow Tower several times a week. It’s lovely when these blogs (as they often do) feel especially for me… Thank you!

LikeLike

It’s interesting how many of us have our own secret Norwich. It would be fun to compare them.

LikeLike

Excellent as usual . Thank you. We didn’t make it back to Norwich due to a busy summer but will be coming soon! Oh wonderful stuff.

LikeLike

Thank you Daniel. What a shame you missed Norwich in record sunshine.

LikeLike

Yes-I see it has been as hot there as our Michigan summers 🙂

Hopefully next year and maybe I will bump into you for a cup of tea from the market.

LikeLike

Tea’s on me, then.

LikeLike

I’ll look forward to it

LikeLike

Another great walk through some of our city’s history. Commercial trading ships were constant visitors to Riverside until well into the 1960’s – the turning basin is still there at St Ann’s Wharf and the gasworks (where the Courts are now) were supplied with coal by barge. The power station (well downstream from Carrow Bridge) was also supplied by water with coasters bringing coal, probably from Newcastle. I look forward to you perambulating along King Street

Don Watson

LikeLike

Hi Don,

What a pity that the river isn’t used for transportation or that there isn’t a continuous riverside walk? I will ‘do’ King Street sometime but the depth of history (not to say the continuing changes to the street) is daunting.

LikeLike

Just ‘re- read this and noticed the truly dreadful pun! Seriously – the channel which once separated the Isle of Thanet from the rest of Kent was the similarly named Wantsum. Do you know the derivation of ‘Wensum’? Could it be an Anglo Saxon word?

LikeLike

I am deeply sorry for the Wensum pun, I couldn’t help myself. According to Wikipedia, “The river receives its name from the Old English adjective wandsum or wendsum, meaning “winding”.

LikeLike

Well, I suppose it’s descriptive of the channel, which did indeed wind. Kent abounds in prosaic place names like River, Bridge and Cliffe

LikeLiked by 1 person

Most enjoyable! I have walked this route a number of times so it is fantastic to learn the history of these bridges and the buildings near them. I loved the pun!

LikeLike

Wouldn’t it be wonderful for there to be a continuous riverside walk? And thanks for supporting the awful pun, Clare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, Reggie! A continuous riverside walk! Serenity.

LikeLike