On his ‘tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain’, 1724-6 Daniel Defoe came to Norwich and wrote: “The walls of this city are reckoned three miles in circumference, taking in more ground than the city of London; but much of that ground lying open in pasture-fields and gardens [1].”

Daniel Defoe, novelist and journalist, on Norfolk Daily Standard Offices (now ‘Fired Earth’) by George Skipper

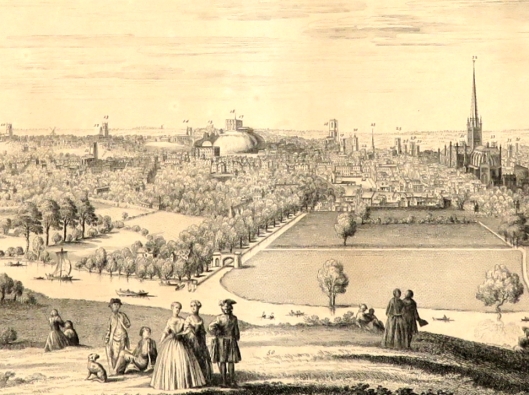

As well as open spaces the walled city was characterised by its trees for in 1662 the historian Thomas Fuller described Norwich as, “either a city in an orchard, or an orchard in a city, so equal are houses and trees blended in it”. The city was still jam-packed with trees nearly a century later …

From, South-East Prospect of the City of Norwich. Samuel and Nathaniel Buck 1741. NWHCM: 1922.135.4:M

Identifying trees from such illustrations is, however, not easy for they are often drawn in artistic shorthand. Even John Sell Cotman – who produced countless studies of trees – was criticised for making them, “as unintelligible to the virtuosi as to the public.” [2]

We can only guess what trees Defoe saw but he is likely to have seen the eponymous tree in Elm Hill.

![Elm Hill elm tree prior to felling [5925] 1978-07-25.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/elm-hill-elm-tree-prior-to-felling-5925-1978-07-25.jpg?w=483&h=723)

An elm in Elm Hill photographed in 1978, six months before it was felled due to Dutch Elm Disease. Courtesy of http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk.

The diseased elm cut down in the 1970s is unlikely to have been alive during Defoe’s visit. What we now see is a London Plane – a species that features prominently in the city’s urban landscape.

The London Plane planted in Elm Hill 1978

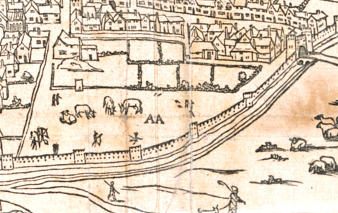

We know from a map of 1559 that Chapelfield Gardens was at one time an archery ground.

Chapel Field, used for archery practice. From Cuningham’s perspectival map of Norwich 1559.

In 1746, the gardens were leased by one-time mayor Thomas Churchman [3] whose mansion was to become the C20 Register Office in nearby Bethel Street.

He enclosed the gardens and planted three avenues of elms that would eventually be replaced with native limes and plane trees [4,5].

Three avenues of elm planted as a triangular walk in Chapel Field by Thomas Churchman. From Samuel King’s 1766 map NWHCM:1997.550.81:M

A century later, the waterworks company had a reservoir in the garden but after an outbreak of cholera they surrendered their interest to the Corporation on the condition that the gardens were to be, “Laid out in the style of London parks”. This was funded by public subscription and in 1880 Mayor Harry Bullard of the city’s brewing family formally opened Chapelfield as a public park [4,5].

By the early C20 there were few other public parks in Norwich but this was to change under the guidance of Parks Superintendent Captain Arnold Sandys-Winsch who, between 1919 and 1956, oversaw the creation of 600 acres of parks and open spaces [6].

Sandys-Winsch (second left) in lock-step with future abdicant Edward VIII at the opening of Eaton Park 1928.

‘The Captain’ planted 20,000 trees and is perhaps best known for the goblet-pruned London Plane trees that line some of the city’s major avenues.

Goblet-pruned London Plane trees along Earlham Road, planted by Sandys-Winsch

The London Plane – the most common tree in London – became an even more common sight in Paris [7,8]. The secret of its success in an urban environment seems to be its habit of discarding pollutants as it sheds large flakes of bark.

One idea is that the London Plane (Platanus x acerifolia) originated around 1650 as a cross between the Oriental Plane (P. orientalis) and the American Sycamore (P. occidentalis) in Southern France or Spain [8]. A more romantic suggestion is that the famous botanist and gardener John Tradescant the Younger (1608-1662) – who took three voyages to Virginia in 1637 – found it as an accidental hybrid in his nursery garden at Vauxhall, London [9]. Tradescant, like his father John Tradescant the Elder, was Keeper of Silkworms for Charles I – the importance of silkworms to the Norwich economy comes later.

Two examples of the parent species, the Oriental Plane, can be seen on Guildhall Hill [8].

According to the historian Herodotus, the Persian king Xerxes came upon an Oriental Plane that he admired so much he adorned it with chains of gold and set someone to guard the tree. In Handel’s opera Xerxes the king stands in the shade of the plane and sings to it the aria Ombra mai fu (Never was a shade) [10]. [Click link to hear Beniamino Gigli sing this courtesy of YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yk_1R9UdIuY]

I remember the devastation caused by The Great Storm of 1987 to the city in general and Chapelfield Gardens in particular.

Balcony in Chapelfield Road damaged by a falling tree in the Great Storm of 1987

With 190 trees Chapelfield Gardens is a significant arboretum, comprised of 45 native and foreign species [5]. Below, the trunk of this London Plane, which occupies a prominent site in the centre of the Gardens, was split down the middle by the Great Storm …

… it was rescued by binding the trunk with metal bands (now removed) and bolting hawsers (still there) through the upper branches to draw them together.

Chestnut trees also provide avenues, as here on Newmarket Road.

But since the beginning of the millennium, browning foliage in the second part of summer shows the damage caused by a leaf-mining moth.

The effects of the horse-chestnut leaf miner, Cameraria ohridella

The oak (Quercus robur), which assumes the status of a national emblem, is said to spend ‘300 years growing, 300 resting and 300 declining’. It can achieve prodigious size: the ancient oak in Earlham Park, just behind UEA Porters’ Lodge, is about 22 feet in circumference [8]. According to The Woodland Trust’s ready-reckoner [11] it might have been an acorn when Henry VII was born (1491), 200 years before Charles I had need of a royal oak in which to hide.

The oldest living thing in Norwich, probably

In 1549, in order to meet the demands for wool for Norwich’s thriving weaving industry, some wealthy landowners from Wymondham – ten miles south-west of Norwich – began to enclose common land on which to graze their sheep. Rebels tore down the fences and so began the uprising led by Robert Kett – a ‘tanner of Windham’ [12]. The rebel army is said to have assembled at Kett’s Oak between Wymondham and Norwich [13].

Kett’s Oak, near Hethersett

But Gerry Barnes and Tom Williamson [14] noted that when measured in 1829 the oak’s girth was only seven feet seven inches. That is, just a third of the circumference of the ancient oak in Earlham Park. According to The Woodland Trust’s ready reckoner [11] it was only about 100 years old at that time, still in its growth phase. In 1933 the hollow tree was painted with bitumen, filled with concrete and corseted with iron bands [14]. Although this survivor commemorates Kett and his followers it seems unlikely to be the original Kett’s Oak.

Kett is also associated with another oak. By the time his army encamped on Mousehold Heath overlooking Norwich, their numbers had swelled to about 16,000. According to C18 historian Francis Blomefield [12] this is where Kett set up court, dispensing the king’s justice beneath the Oak of Reformation.

‘Robert Kett sitting under the Oak of Reformation assuming Regal Authority’ by Wale 1778. Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service NWHCM: 1954.138.Todd5.Norwich.193

After skirmishes in and around the city the rebel army was drawn eastward into the Battle of Dussindale (near Boundary Lane, Thorpe St Andrews) where they were defeated by a superior army of 14,000 reinforced by German mercenaries [13]. Nine of Kett’s men were hanged from the Oak of Reformation [12]; Kett himself was hanged in chains from the walls of Norwich Castle but the same walls now bear a plaque declaring him a local hero.

In 1549 AD Robert Kett yeoman farmer of Wymondham was executed by hanging in this castle after the defeat of the Norfolk Rebellion of which he was the leader

In 1949 AD – four hundred years later – this memorial was placed here by the citizens of Norwich in reparation and honour to a notable and courageous leader in the long struggle of the common people of England to escape from a servile life into the freedom of just conditions.

Oak Street in Norwich seems to have derived its name from the C15 church, St Martin at Oak. According to Blomefield [12] the church was named after, ” a famous image of the Virgin Mary, placed in the oak, which grew in the churchyard…” , making it a site of pilgrimage. The church was badly damaged in the Blitz and from 1976-2002 was in the care of St Martins Housing Trust – a charity for the homeless.

St Martin’s at Oak 1931, and after restoration in 1955. ©www.georgeplunkett.co.uk

Norwich takes pride in having the greatest density of medieval churches “north of the Alps” (for those who might confuse us with Rome). Of the 58 pre-Reformation churches built within its city walls, more than 30 still stand [15]. In the Heavenly Gardens project, George Ishmael and colleagues plan to interconnect the often underused churchyards into a publicly accessible botanical garden[16]. Trails involving 28 medieval churchyards are covered in the first five (of six) downloadable PDFs (http://www.heavenlygardens.org.uk/churchyard-trails/).

On my visit to one of George’s churchyards, St Stephens, this rare Himalayan Euodia fraxinifolia was in flower.

Chiming with the Heavenly Gardens project, a Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) grows outside St Peter Hungate at the top of Elm Hill. This is the church where, in 1466, John Paston’s body rested for one night before his grandiose funeral in Bromholm Priory [17]. The Tree of Heaven was introduced into Britain from Western China in 1751. Its leaves are used in silkworm culture although I can find no record of it being used for that purpose in Norwich.

The Stuarts, like the Elizabethans before them, were often portrayed in fine silk clothing. Not long after coming to the English throne (1609) King James I tried to invigorate the domestic silk trade, and to compete with the French, by offering mulberry saplings to his Lord Lieutenants at ‘six shillings the hundred‘. These were not, however, the preferred White Mulberry (Morus alba) grown in China but the Persian Black Mulberry (Morus nigra). Silkworms can feed on the Black Mulberry but – in a surprising example of ‘you are what you eat’ – the larvae then produce coarser silk and less of it, causing King James’ experiment to fail [18]. Over two centuries later, Norwich silk mills (e.g., St Mary’s Silk Mills in Oak Street and the Albion Yarn Mills in King Street) were using raw silk imported from China. Once more, there was an attempt to produce English silk: a “silk company established in 1835 planted upwards of 1500 mulberry trees on two acres of land in Thorpe Hamlet, stocked with 40,000 silkworms” [19] but this, too, failed.

The mulberry tree growing in St Augustine’s churchyard has a particular relevance since it celebrates the life and work of silk weaver Thomas Clabburn, buried in its shadow.

Mulberry in St Augustine’s churchyard; left, the Clabburn family burial plot

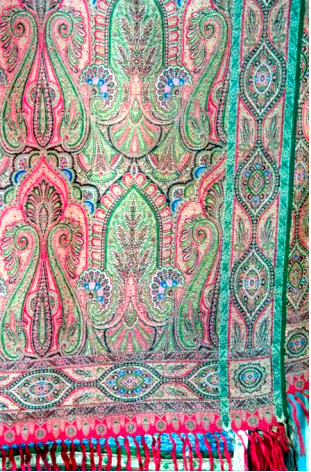

Norwich shawls were hugely popular in the mid-C19, due largely to Queen Victoria’s patronage [20]. The firm of Clabburn, Sons and Crisp were prominent members of this industry; they patented a method for producing the same pattern on both sides and sent examples to the royal family. Thomas was evidently a benevolent employer: upwards of 600 Norwich weavers and assistants subscribed to a memorial plaque inside the church extolling him as, “a kind good man.”

Jacquard silk shawl c1850 woven by Clabburn, Sons and Crisp

Norwich and the Tree of Life. Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) is famed for his method of classifying plants and animals in hierarchical groups according to shared family characteristics. This paved the way for Darwin’s Tree of Life in which such groupings are not seen as fixed but related through time by evolution. When Linnaeus died, James Edward Smith (1759-1828), the son of a wool merchant and Norwich mayor, used his father’s wealth to buy the Linnean collection of books and – more importantly – his herbarium of dried plants containing examples of ‘standard types’ (see a previous post [21]). When this collection came to Norwich it was visited by naturalists from around the scientific world. Smith’s wonderful garden once contained many rare species but now lies beneath the Surrey Street bus station. He is commemorated by the West Himalayan Spruce, Picea smithiana, named after “the late immortal President of the Linnean Society.”

Picea smithiana, the Morinda Spruce, named for Norwich naturalist Sir James Edward Smith ©Vyacheslav Argenberg

©2018 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- Daniel Defoe (1722). A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain. Tour through the Eastern Counties of England, 1722, available as an e-book: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/983/983-h/983-h.htm

- From, The Norwich Mercury. Quoted by Josephine Walpole (1993) in ‘Leonard Squirrell: The Last of the Norwich School?’ Pub. Antique Collectors’ Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk.

- http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk/monuments/Thomas%20Churchman/Thomas_Churchman.shtmhttp:/

- /www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/parksandgardens.htm

- http://www.chapelfieldsociety.org.uk/arboretum/

- http://friendsofeatonpark.co.uk/captain-sandys-winsch/

- https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/environment/parks-green-spaces-and-biodiversity/trees-and-woodlands/london-tree-map#acc-i-44112

- Rex Hancey (2005). Notable Trees of Norwich. Pub: Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists’ Society.

- https://londonist.com/2015/03/the-secret-history-of-the-london-plane-tree

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Platanus_orientalis

- http://www.wbrc.org.uk/atp/Estimating%20Age%20of%20Oaks%20-%20Woodland%20Trust.pdf

- Francis Blomefield (1806). https://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-hist-norfolk/vol3

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kett%27s_Rebellion

- Gerry Barnes and Tom Williamson (2011). Ancient Trees in the Landscape: Norfolk’s Arboreal Heritage. Pub: Windgather Press.

- https://norwichmedievalchurches.org/

- http://www.heavenlygardens.org.uk/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/12/15/the-pastons-in-norwich/

- https://www.moruslondinium.org/research/faq

- William White (1836). History, Gazetteer, and Directory of Norfolk, and the City and County of Norwich. Pub: William White, Sheffield.

- Caroline Goldthorpe (1989). From Queen to Empress: Victorian Dress 1837-1877. Pub: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/01/15/when-norwich-was-the-centre-of-the-world/

Thank you: George Ishmael of Heavenly Gardens (and Olly Ishmael); James Emerson, Secretary, Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists Society; Clare Haynes of UEA History; Hazel Harrison of the Chapel Field Society; Kerrie Jenkins of The Woodland Trust; Paris Agar, Norfolk Museums Service; Lesley Cunneen, garden historian; Joy Evitt, Norwich silk historian.

Love the goblet-pruned planes

LikeLike

Hello Reggie, that was an enjoyable account. The trees of England are great – most seem to grow better and faster than here on the continent. I don’t know why, but cedar trees (Cedrus atlantica) in Germany never get the magnificent shape they do e.g. in Mannington Hall.

There is a little sunken garden in Earlham park, right in the middle, next to the hall. Some tree rarities got planted there once, but the whole area has been neclected and nature has created a dense little forest. Nonetheless, the kids like playing there. Do you know what this was meant to be?

Best wishes, Henrik

LikeLike

Hi Henrik, I shall have to go an explore Earlham Hall with my in-house tree expert. In the meantime, Norfolk Heritage Explorer says this of Earlham Hall: The area immediately to the north of the hall which consists of horse chestnuts may be the remnants of a grove associated with the early eighteenth century gardens. There are also a number of pits and irregular depressions within the park which are probably the result of gravel extraction although some may also have been used for marl, these were obscured by tree planting when the park was formed. The present dove house (NHER 9414) was probably built in the late eighteenth century, although an earlier dove house to the north-east of the hall preceded it.

From the end of the eighteenth century the main entrance drive to the hall was from the south east. In the early nineteenth century the north east drive was in place but the lodge was not built until the end of the century or possibly the beginning of the twentieth. Nineteenth century walks surround the western side of the hall, banks within this area are the earthworks of earlier gardens. A walled garden, sunken garden, rock garden and kitchen garden lie to the south-east of the hall. An ice house also to the south east of the house is shown on (S8). The southern belt of the park was planted between 1843 and (S9).

I’ll get back to you. All best, Reggie

LikeLike

Such a full and fascinating post. Can we have something on the Norwich Pleasure Gardens please?

There is a Norfolk Archaeology article ….reference eludes me

LikeLike

‘Pleasure gardens’ are definitely on my long list and I do have that Norfolk Archaeology article … somewhere. Thanks Jill.

LikeLike

I’d second a pleasure gardens posting. The article is Trevor Fawcett’s “Norwich pleasure gardens” in Norfolk Archaeology 35(3), 1972, pp. 382-9. A fascinating read. Fawcett also wrote some interesting articles about the art, music and book club scene in Norwich in the 18th century before moving on to Bath and becoming an expert in that city’s 18th century culture. He died last year: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/oct/17/trevor-fawcett-obituary

LikeLike

Thank you Grant, Pleasure Gardens it is … on the shortlist. Reggie

LikeLike

This post was such a joy to read! I will have to go tree spotting in Norwich now! Thank you so much for drawing the Heavenly Gardens scheme to my attention.

LikeLike

The Heavenly Gardens Scheme is a great idea – happy tree-spotting Clare

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Reggie!

LikeLike

Dear Reggie, Further to your essay on trees in Norwich, I very much regret that the splendid oak tree in the former horse pasture in Fairfield Road has been chopped down. As far as I know, this was the finest oak tree in Norwich and possibly in the whole county. It must have been some two hundred years old. It was tall, with finely spaced branches and looked in good health but was felled very recently, I imagine because it was considered a hazard in what is now a sports ground for the Town Close School. Yours sincerely, Alastair Grieve.

.

LikeLike

Dear Alastair, One would have assumed that there was a Tree Protection Order on such a magnificent tree – it’s worth checking the TPO register in the City Hall. As you say, perhaps this was overridden by safety concerns but oak trees do, quite naturally, shed branches over the hundreds of years they take to decline and eventually die and one wonders if there was a more imaginative way in which the tree could have been left to do this in peace.

LikeLike

Yet again you have excelled yourself. I must have a further look at the mulberry tree in St Augustine’s churchyard. Until the late 1980’s there was a prolific mulberry where John Lewis’s car park now is. We lived on Grove Road at the time and I have taken a step ladder down to pick them. Messy but nice

Don Watson

LikeLike

Thank you Don. Mulberry is such a wonderful fruit with such an elusive flavour. I used to pick the tree in Golden Dog Lane when passing but that has now disappeared.

LikeLike

Just a note: the London PlaneS along both Colman and Earlham Rds are Platanus x Hispanica , and for info the goblet shape was created by way of fixing canes from the pollard points in the 50’s.

LikeLike

Thank you for the information on how the goblet shape was created (mentioned in the ‘Norwich: City of Trees’ post). Were you involved with this? As I’m sure you know, the specific names x hispanica and x acerifolia are synonymous for the London Plane, although the latter seems to be used more commonly nowadays.

LikeLike

What a great blog!

Regarding the plane tree in Chapelfield Gardens that split during the gale of 1987: the tree was pulled together and held with metal bands but no one ever knew who did it! The Council later removed the bands, which had undoubtedly saved the tree, and replaced them with the steel cables.

The history of mulberry trees is fascinating: if you want to see a white mulberry (the one that silk-worms prefer) there is a recently planted one on the Green in front of the Birdcage pub in Pottergate.

LikeLike

How intriguing about the Chapelfield tree rescue. Who could have done this in plain view? And so good to hear about the planting of the white mulberry tree on St Gregory’s Plain – a tree so important to our lost silk industry. Thank you HG.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Captain’s Parks | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH