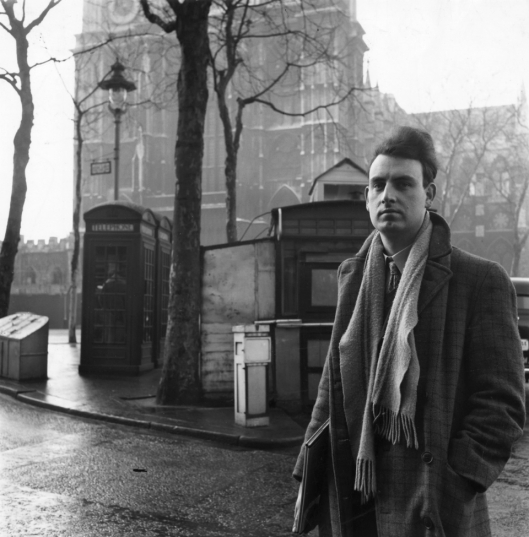

Born in Bedford 1930, dead of cirrhosis of the liver 1983, Ian Nairn wrote about towns not as a trained architect but as an outsider [1,2]. In 1955 he produced a maverick edition of Architectural Review entitled Outrage in which he railed against the homogenising effect of bland postwar development and the blurring of lines between town and country – ‘urban sprawl’. The result was a subtopia (his word) in which “the end of Southampton will look like the beginning of Carlisle.” He also wrote about Norwich … and not in a good way.

Ian Nairn. Photo: Architectural Press Archive/RIBA Library Photographs Collection

Nairn was stationed on the outskirts of Norwich at RAF Horsham St Faith, now Norwich Airport. On a personal mission for Architectural Review, Nairn flew his Gloster Meteor jet in search of evidence of John Soane’s 1784 Music Room at Earsham Hall [2].

John Soane remodelled the Music Room at Earsham Hall, near Bungay, 1784. He also designed Shotesham Hall, just outside Norwich, 1785. © Evelyn Simak

Nairn is said not to have been able to separate his private from his professional life so it was probably to the city’s detriment that Norwich was the only one of the 16 ‘Nairn’s Towns’ in which he had actually lived (other than London). The two uneventful years he spent on the celestial Unthank Road with his first wife, Joan Parsons, allowed him far longer to polish his hostility than was possible on the other provincial drive-bys. His 1964 essay on Norwich was “particularly rancid” [2] …

“… the traveller comes on a brand-new building announcing the city centre at the southern end of St Stephens Street, which for crushing banality must have few equals in Britain … to come first in a field as large as this is no joke.” [3]

St Stephens Street was flattened in the war after which it was decided that there was nothing worth saving except – according to Pevsner and Wilson [4] – Marks & Spencer’s 1912 Adam Revival building, formerly Buntings Department Store. In his 1967 postscript, Nairn wrote that the rebuilding of St Stephens Street was “probably the worst thing of its kind I have ever seen in what passes for a cultured city.”

The western side of St Stephens Street – an unconsidered jumble of post-war building

By contrast, Nairn loved George Skipper’s ‘old’ Norwich Union building (1900-1912) in nearby Surrey Street, calling it “a super-Palladian palace which is as good as anything of its style in the country.” But the adjacent new headquarters were “a completely anonymous slab” [3].

Skipper’s Norwich Union building of 1903-4 next to the 1960-1 building by T P Bennet & Sons ‘without the conviction Skipper wielded in his day” [3].

Like fellow ‘dilettante journalist’ and architectural commentator, John Betjeman, Nairn approved of our local architect, identifying the Telephone Manager’s Office in St Giles Street as, “another firework by Skipper … smaller but if anything even richer.” Built 1904-6 for the Norwich and London Accident Insurance Association (now St Giles House Hotel) it has been called “the Norwich Union in miniature” [4].

Nairn loved the unlovable; he was neutral about historic Elm Hill “with its cobbles and antique shops” but he outrightly condemned the decline of Pottergate and King Street. Despite suffering from faceless post-war infill Pottergate manages to thrive as part of a vibrant mix of independent shops in the Norwich Lanes. King Street, however, has changed more dramatically since Nairn’s visit.

125-129 King Street in 1946. ©www.georgeplunkett.co.uk. Compare with below.

After George Plunkett took the above photograph the ground floor of 125-129 was ripped out and the shop fronts replaced with plate glass, the full horror of which can be seen now that the building is derelict. This is adjacent to Dragon Hall (under scaffolding), one of the ‘Norwich 12’ iconic buildings. Further along, behind the hoarding is the new St Anne’s Wharf housing development; the opposite side is now mainly modern housing in ‘traditional’ style and so character developed over centuries has all but evaporated.

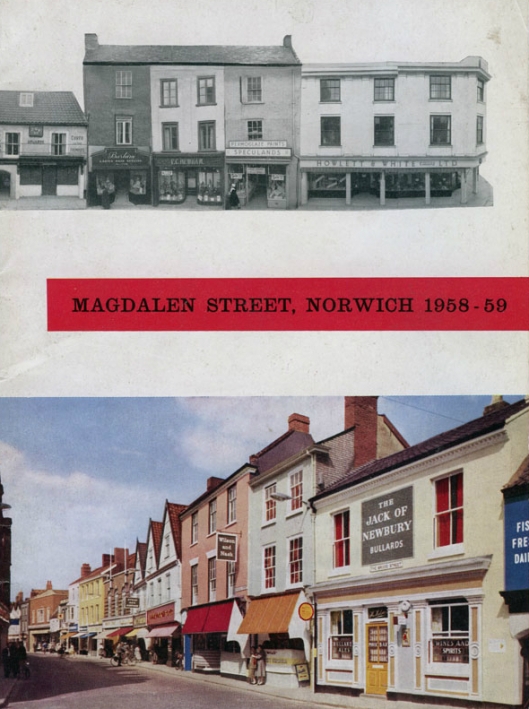

To the north of the city the spirit of the Coslany ward, said Nairn, had been stifled by “over-zoning and carelessness“. In the first of the Civic Trust’s redecoration schemes (1959) attempts had been made to revive Magdalen Street, as can be seen in a short film [5]. Facades were stripped of unnecessary clutter and painted in pastel shades from a palette of 18 colours and 13 alphabets selected by Coordinating Architect, Misha Black. However, while The Times reported on the Walt Disney effect [6], Nairn – citing one of the ‘malpractices’ from Outrage – wrote that the pastels were “cruelly out of touch with the local colour-range, and after five years it looks as jaded as last year’s fashion.”

Before and after: book cover of Civic Trust 1959 project. From the archives of The Royal Windsor Forum

Nairn did manage to extract a few good points, singling out plans by City Architect David Percival for the old people’s flats clustered around the churchyard of St John Ber Street but, sixty years on, it is hard to share the warmth of Nairn’s enthusiasm.

Alderson Place, Finkelgate

Another of Nairn’s bright spots was Denys Lasdun’s University of East Anglia campus. Lasdun designed the campus to face the newly-excavated lake with the ‘teaching wall’ behind; this was separated by an elevated walkway from the ziggurats – the stepped boxes providing student accommodation. In his 1967 postscript, Nairn was evidently minded to approve this icon of New Brutalism on principle since building had only just begun.

Lasdun’s “laudanum dream of Anglicised modern architecture” [7]

Nairn did concede that there were still many marvellous things to see in Norwich, including “one of the great town views of England.”

He thought the Anglican Cathedral had never received the praise it was due although his own praise was correspondingly muted: “no fireworks”.

“Such a balanced and even-tempered masterpiece”

He did like the Perpendicular vaulting added to the Norman nave after the timber roof was destroyed by fire in 1463; he thought it “a splendid match for the three-storey elevation underneath.” It is a glorious stone roof, a masterpiece of late medieval craftsmanship, but you would hardly call it a ‘match’ since it is hard to disguise the stylistic chasm between the delicate lacework of lierne ribs and the ponderous Norman piers made of lighter Caen stone.

Supporting one of the Perpendicular fans is a hart lying on water – the rebus of Bishop Walter Lyhart who initiated the vaulting of the nave roof.

The only other building in Norwich “with the authority of the cathedral” was St James Yarn Mill on the Wensum, built in 1843 to give a boost to our waning textile trade. Nairn’s first wife worked for local printers and booksellers Jarrolds, whose printing works were then in St James Mill; according to Gillian Darley it was Nairn’s intervention that gained the building its Grade I listing in 1954 [8].

As he wrote words of praise about this temple of industry Nairn was using his other hand to take a swipe at “the intricate antics of the city’s interminable late-Gothic churches. Interminable is about right“. He liked the interior of St George Colegate but then its Gothic fittings had been replaced with unfussy Georgian.

“Good things have to be hunted down piecemeal like … the enchanting toy vault under the tower of St Gregory Pottergate” (below).

The toy vault

At St Peter Mancroft, Nairn said nothing about one of the best angel roofs in the country nor of the outstanding C15 Norwich School glass in the great east window. Instead, he thought the building “one of the most neurotic and inconsistent designs that ever received universal adulation.” But in this he was at odds with Nikolaus Pevsner, with whom he had co-edited the 1960s volumes on Sussex and Surrey for The Buildings of England. Pevsner – who thought Nairn’s contributions too subjective – judged St Peter Mancroft “the Norfolk parish church par excellence”; John Betjeman thought it “superb” [9]; and Simon Jenkins wrote, “Few who enter St Peter’s for the first time can stifle a gasp” [10].

Within spitting distance of St Peter Mancroft (too close for a dyspeptic critic) is the City Hall. St Peter Mancroft was “old, big and has a lot of carving on it” but the very freedom from fuss that Nairn admired in Jarrolds Paper Mill was positively disliked at City Hall: it was timorous, suffering from a fatal “drawing back from commitment.”

Nairn summed up City Hall’s personality defects by comparing “the empty bombast of the lions in front … with their C12 prototype in Brunswick.” Both are quite stylised, both things of beauty. The Norwich lion (left) does have a slicker hair-do but this was at a time when Norwich City Council was demolishing hundreds of medieval slums, looking forward to the streamlined kind of future promised by Swedish Neoclassical architecture [4].

In opposition to Nairn’s glumness, Pevsner and Wilson thought Norwich City Hall “must go down in history as the foremost English public building of between the wars … (an) architectural triumph” [4].

Pevsner & Wilson [4] noted the influence of Stockholm City Hall by Ragnar Östberg (1923) and Stockholm’s Concert Hall by Ivar Tengbom (1926) on Norwich City Hall (1939)

Below City Hall lies the large marketplace founded by the Normans in their New Borough and joined umbilically to their castle by Davey Place. Nairn was enthusiastic about this little street and thought “This part of Norwich could be nowhere else.”

Davey Place below the Castle. © Museum of Norwich at the Bridewell, courtesy of Picture Norfolk

Davey Place is not without charm but is no longer unique, marred by blank-faced intrusions from the C20th.

In his 1967 postscript Nairn wrote:

The highlight of 1965 was the approval of a proposal by the City Engineer to build a flyover exactly half-way down that recently famous Magdalen Street; meanwhile, a property company has bought up large chunks of ‘old rubbish’ to the north; the character of Coslany has finally gone.

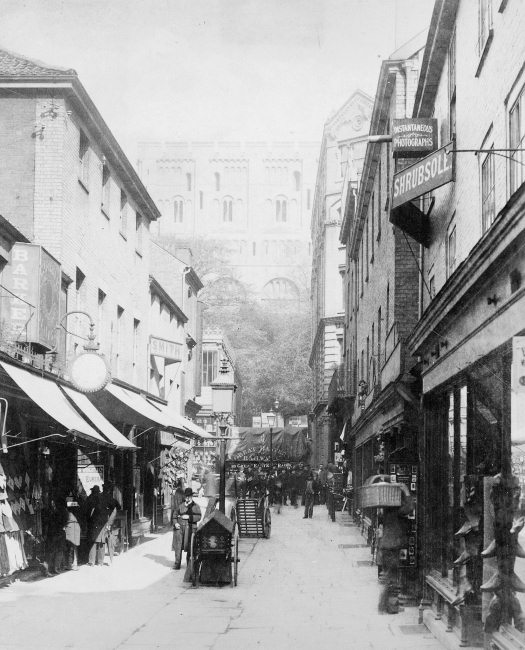

Lovely old Magdalen Street barely survived the bisection.

The flyover that bisects Magdalen Street. Looming on the left is the Hollywood Cinema, part of the failed Anglia Square development.

On Nairn’s ‘chunks of old rubbish’, immediately behind Magdalen Street, the St Augustine’s area was bulldozed so that Norwich could have its own copy of urban revitalisation – the pedestrian precinct. The problem was that pedestrians had a long walk from the city centre to a satellite from which they were notionally excluded by the new inner ring road [see previous posts 11 ,12]. Now, Anglia Square is a collection of downmarket discount stores, the multi-storey carpark is closed, the excessive surface parking around the uncompleted development is tatty, and Her Majesty’s Stationery Office – the love-it-or-hate-it Sovereign House – lies abandoned [13].

The Brutalist Sovereign House, part of the Anglia Square development (1970)

Around the time of his second visit to Norwich, Nairn was falling out of love with ‘new architecture’, using the front of the Observer’s Review to shout: “Stop the architects now. The outstanding and appalling fact about modern architecture is that it is not good enough” [14]. The lesson learned from the last 70 years of post-war town planning is that open urban space needs to be on a human scale and in tune with the historic environment if it is to be loved. It is therefore hard to comprehend why plans have been submitted to redevelop Anglia Square with a 25-storey tower. Whether it is 25 or a concessionary 20 storeys high is immaterial for any tall tower plus three large 12-storey blocks will be cruelly out of scale with the surrounding Conservation Areas [15]. It is essential that the overriding values of retail and property are not allowed to determine the texture of the streetscape for a further 70 years. Click to read the Norwich Society’s response to the revised Anglia Square proposal [16]

©2018 Reggie Unthank

FOR YOUR CHRISTMAS STOCKING The book of ‘Colonel Unthank and the Golden Triangle’ contains much more about the development of the Golden Triangle than covered in my blog posts, including photographs of the Unthank family.

Sources

- Ian Nairn (1955). Outrage. Architectural Review 1 June 1955.

- Gillian Darley and David McKie (2013). Ian Nairn: Words in Place. Pub: Five Leaves Publications.

- Ian Nairn (1964). Norwich: Regional Capital. In, Nairn’s Towns, edited and updated by Owen Hatherley (2013). Pub: Notting Hill Editions Ltd.

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1. Yale University Press.

- http://www.eafa.org.uk/catalogue/304

- ‘Norwich’s Skilful Use of Colour’, The Times, 13 April 1959.

- Owen Hatherley (2013). In, 2013 postscript to Norwich: Regional Capital by Ian Nairn. From Nairn’s Towns (Introduced by Owen Hatherley, Pub: Notting Hill Editions).

- Gillian Darley (personal communication).

- John Betjeman (updated by Richard Surman) (2011). Betjeman’s Best British Churches. Pub: Collins.

- Simon Jenkins (1999). England’s Thousand Best Churches. Pub: Penguin Books.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/11/15/reggie-through-the-underpass/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/10/15/gildencroft-and-psychogeography/

- https://c20society.org.uk/botm/sovereign-house-norwich/

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/nov/03/ian-nairn-architecture-critic-against-sprawl-biography

- http://www.edp24.co.uk/news/politics/anglia-square-revised-plans-due-but-will-controversial-tower-s-height-be-cut-1-5668872

- https://www.thenorwichsociety.org.uk/future-norwich/anglia-square

Thanks. For permission to reproduce images I am grateful to Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk and to Roger, editor of The Royal Windsor Forum

Mr Nairn was certainly a bit harsh on some things but spot on with others. Norwich has always had its architectural problems but some excellence too.

LikeLike

I agree, Nairn was spot on about some aspects of Norwich i.e., St Stephens Street and I wish he’d revisited Magdalen Street/Anglia Square several years later. But he was unnecessarily mean-spirited about the city’s ancient treasures.

LikeLike

Fascinating. Many thanks. Of course, David Percival was also responsible for the much hated library that burnt down with the loss of so many historic records.

LikeLike

Thank you Jeremy. I was no fan of the old library and think the new one a great improvement that manages not to detract from St Peter Mancroft.

LikeLike

Presumably Ian Nairn disliked what is now Wilko’s – built as the Co-op. Some of that side of St Stephens is pre-war, the other side was completely rebuilt in the 1960’s to widen what was a relatively narrow road. Perhaps flying the unloved Meteor gave him a jaundiced view of Norwich, Another excellent post.

Don Watson

LikeLike

Hi Don, I think you are right, Nairn must have been thinking about the curved Co-op/Wilko building and possibly the matching curve of the NCP carpark on the opposite side of the street. Together, they make a truly shameful gateway to the city. The awful east side of St Stephens was rebuilt, as you mention, to widen the road and the texture of the ‘prewar’ side depends entirely on whatever the owners of individual sites thought would make an appropriate shopfront. There is no coherence, no grand vision. And now that it has been allowed to become an overspill bus station St Stephens Street inexorably morphs into Anglia Square.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another excellent and interesting post, Reggie! I love the old film you unearthed and the before and after photos are very revealing. I do hope the high-rise buildings are not built in Anglia Square.

LikeLike

Hi Clare, Another fascinating old film was made in 1950, driving around Norwich as part of the City Engineer’s road-widening scheme: http://www.eafa.org.uk/catalogue/908

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, for this one too. All those bomb sites and people walking out in front of vehicles without looking!

LikeLike

It’s interesting to see what the planners had to play with after the war.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Vanishing Plains | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH