The Dukes of Norfolk are conspicuously absent from the county that bears the name of their title; for over 400 years their seat has been at Arundel Castle, Sussex, and barely a trace of them remains in Norfolk’s county town.

Arundel Castle, Sussex ca 1770 by James Canter ©Arundel Castle

But before sifting Norwich for the remains of the Dukes of Norfolk let’s look at the ebb and flow of power (and religion) that explains their absence.

Earlier lineages of the Dukes of Norfolk had petered out so, in the latest line, John Howard was created the First Duke of Norfolk in 1483 by Richard III as reward for helping him usurp the throne. Howard died at the Battle of Bosworth, along with Richard III, when struck in the face by an arrow. Howard’s son, who also fought at Bosworth, was placed in the Tower and stripped of lands and title by the victor, Henry VII. Henry VII restored the title of Surrey but it wasn’t until the reign of Henry VIII that the title, (Third) Duke of Norfolk, was restored after Thomas Howard defeated James IV at Flodden.”

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk by Hans Holbein the Younger, holding the baton of the premier Earl Marshal. Courtesy Royal Collection.

As a religious conservative the Third Duke challenged the reforms of Henry VIII’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, but gained the upper hand when Cromwell fell out of favour for promoting the king’s unsuccessful marriage to Anne of Cleves.

Anne of Cleves by Hans Holbein the Younger. Henry said “She is nothing as fair as she hath been reported” . The marriage was unconsummated. Credit: Louvre Museum

Cromwell was accused of treason and it was Norfolk who snatched the chains from the neck of the condemned Chancellor, “relishing the opportunity to restore this low-born man to his former status”.

Thomas Cromwell’s Garter Collar

But in this noble game of snakes and ladders the Duke of Norfolk had the great misfortune of being uncle to Henry’s two beheaded wives – the first being Anne Boleyn (Wife II) from Blickling. The second was Catherine Howard who Henry married on the day that Cromwell was beheaded, just three weeks after divorcing Anne of Cleves (Wife IV). It was Catherine’s supposed promiscuity that led to her execution and the Howards’ loss of power [1].

The Third Duke’s son, Henry Howard, has been called: “the most folish prowde boy that ys in Englande”.

Henry Howard, ‘The Poet Earl of Surrey’, aged 29 (1546). Attributed to William Scrots

Henry Howard unwisely improved his coat of arms in the family’s Kenninghall Palace in South Norfolk by quartering them with the royal arms of his ancestor, Edward the Confessor. Henry VIII saw this as treasonous so Howard who, as a young man had been made to witness the execution of his relative Queen Catherine Howard, was himself beheaded aged 30 [2].

The attainted arms of Henry Howard. The arms of Edward the Confessor are fifth in this series (Azure, a cross flory between 5 marlets Or)

His father, the Third Duke was also in the Tower, but was reprieved by Henry VIII’s death the day before the planned execution. After Henry’s daughter, Bloody Mary – who burned dozens of Norwich Protestants at Lollards’ Pit – became queen she rewarded the staunchly Catholic Howards by restoring the Dukedom of Norfolk. After Henry’s other daughter – the staunchly Protestant Elizabeth – became queen the Fourth Duke of Norfolk was found guilty of plotting against her and so, once more, lands and title were forfeit.

The Fourth Duke of Norfolk, Thomas Howard, is suggested to have commissioned Thomas Tallis’ 40-part motet Spem in Alium; after hearing of Striggio’s 40-part mass he asked “whether none of our Englishmen could sett as good a songe” [3]. For this alone he is my favourite Norfolk. During the 2010 Norfolk and Norwich Festival I heard Spem in Alium played in St Peter Parmentergate on King Street. Janet Cardiff had arranged 40 speakers so that the audience could walk around and listen to recordings of each of the 40 voices played through a dedicated audio channel [4]. Magical.

Janet Cardiff’s 40-speaker motet in St Peter Parmentergate. Courtesy of [3]

Arundel Castle became the Howard seat after Thomas Howard married Mary Fitzalan, the Earl of Arundel’s heir, in 1555. But the duke became embroiled in a Catholic conspiracy to enthrone Mary Queen of Scots. He was executed by Elizabeth I and Norfolk lands and titles were – yet again – held forfeit. It wasn’t until 1660, during the Restoration, that these were restored to the Fourth Duke’s great-great-grandson who was held in a mental asylum in Padua and on his death the title passed to his brother, the Sixth Duke [5,6].

Henry Howard, Sixth Duke of Norfolk, Earl Marshal, 1st Earl of Norwich (ca 1670-80?)

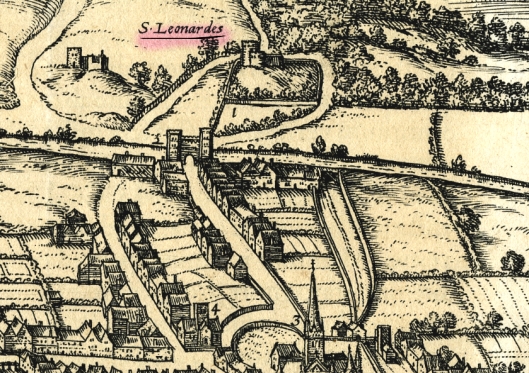

The Howards in Norwich. In 1544 the Third Duke’s son, (that most folish prowde boy) had begun building a sumptuous mansion on the site of St Leonard’s Priory given to the Norfolks by Henry VIII. On St Leonard’s Hill the building, Mount Surrey [7], looked over the city; five years later Robert Kett’s army used the mansion as its headquarters after which it was totally demolished [8].

Site of Mount Surrey, on St Leonard’s Hill (to the right of ‘Leonardes’), overlooking Bishop Bridge (twin towers, centre) and the cathedral spire (lower edge). From Braun & Hogenberg’s map 1581. Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Collections.

The Poet Earl’s other house in Surrey Street, Surrey Court, was barely finished by the time of his execution. It was on this site that George Skipper was to build Surrey House, aka The Marble Hall, for Norwich Union, 1901-1906 [9]. Some of Surrey’s C17 stained-glass coats-of-arms were reinstalled in Skipper’s building that – had they been seen by his prosecutors – would have confirmed their accusations of Surrey’s and Norfolk’s treasonous intentions [10].

C17 glass from Surrey Court now in Aviva’s Surrey House. Lower far right is the Third Duke’s coat of arms surrounded by the Order of the Garter, surmounted by the ducal crown. On this shield the Howard arms occupies the top left quadrant with ancestral arms in the remaining quarters.

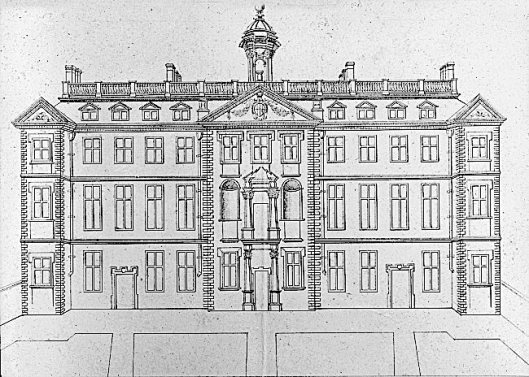

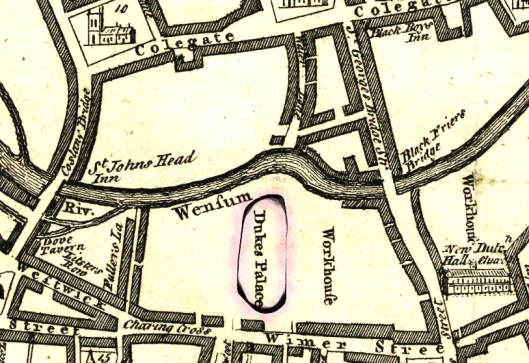

Around 1540, on what is now the site of the Duke Street Car Park, the Third Duke built his own palace as a copy of Surrey House on the other side of the city [11]. This is where the Fourth Duke wooed the devoutly Catholic Mary Queen of Scots with talk of marriage that earned him Elizabeth I’s disapproval [quoted in 12]. In 1672 the palace was rebuilt in the modern Italianate style but probably never completed.

The north side of Duke of Norfolk’s Palace, John Kirkpatrick 1710. Courtesy Norfolk County Council, at Picture Norfolk

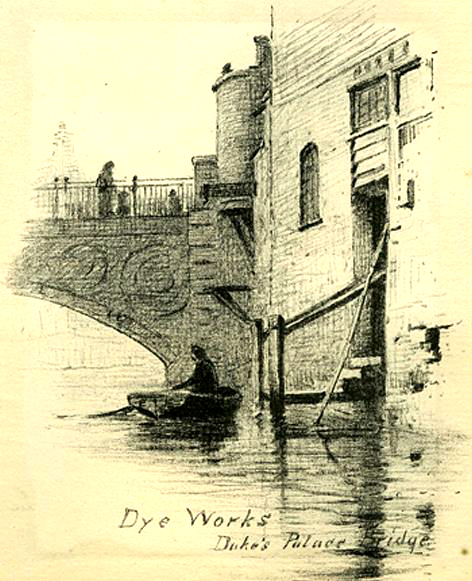

Thomas Baskerville (1681) didn’t hold back: (it is)“seated in a dung-hole place … it hath but little room for gardens … and is pent up on all sides … with tradesmen’s and dyers’ houses, who foul the water by their constant washing and cleaning their cloth” [10]. As we saw in the post on the Blood Red River [13] waste was still being emptied into the Wensum from adjacent dyeing houses some 200 years later.

The cast-iron Duke’s Palace Bridge (built 1822) next to Michael Stark’s dye works. Drawn by James Stark. Courtesy of [15].

One reason why the palace was abandoned in 1711 was that the cellars had been sunk so deep “that the water annoyed them much” and the floors above subsided [14]. An image from a recent post shows just how devastating the slow-flowing Wensum can be [13].

The flooded Anchor Quay Brewery in 1912, a few hundred metres downstream. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council, at Picture Norfolk

Another reason for the Eighth Duke’s departure from Norwich is claimed to have been the mayor’s refusal (1708) to allow him to process into the city with his comedians and trumpeters [8]. It does sound mean-spirited but there are deeper currents. Blomefield [7] records that in 1683 the Earl of Arundel had brought letters from Charles II (who made a death-bed conversion to Catholicism) limiting the ancient rights of the Norwich Assembly. Charles’ successor, the Catholic James II, also tried to impose direct control upon the Assembly. In 1688 Henry Duke of Norfolk rode into the marketplace at the head of 30 knights and gentlemen and declared for a free parliament; i.e., that Catholics should be free of a test that effectively barred them from both Houses of Parliament. That year, the Norwich ‘rabble’ rioted and burned a Popish chapel and houses [7]. Charitably, the mayor’s refusal to permit the procession can be seen as a sensible precaution against stirring up the Protestant mob but now that an intensely Anglican monarch (Queen Anne) was on the throne the Assembly may have felt safe in thumbing their noses at the Catholic nobility after years of interference.

Made of stone – a rarity in Norwich – the Tuscan columns on Mayor John Harvey’s house at No 20 Colegate are said to be recycled from the Duke’s Palace [8 and, more ambiguously, 16].

The domestic wing of the Duke’s Palace was leased to the Corporation in 1711 as a workhouse [11].

The workhouse. Samuel King 1766. Courtesy, Norfolk Museums Service NWHCM: 1997.550.81:M

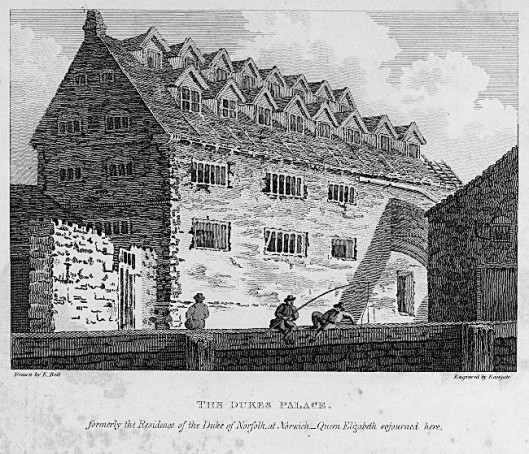

The Court of Guardians (of the Poor) inserted a great number of dormer windows into the former bowling alley to let light into the paupers’ dormitories; lower floors provided workrooms.

Workhouse, formerly the duke’s bowling alley. By Eastgate ca 1806. Courtesy Norfolk County Council, at Picture Norfolk

In 1764 the Tenth Duke built a Roman Catholic chapel with a chaplain’s house on the site

The derelict former Catholic chapel, presumably in the 1960s. Courtesy Norfolk County Council, at Picture Norfolk

… but in 1794 his successor, who was Anglican, let the chapel to the Norwich Public Library [18, 19]. This particular link with the Dukes of Norfolk was finally broken in 1839 when chapel and house were sold to the Norfolk and Norwich Museum; in the 1960s the building (by then a billiard hall) was demolished to make way for the Duke Street Car Park.

The Old Public Library ca 1900 on St Andrew’s Street. Courtesy Norfolk County Council at http://www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

The link with the Dukes of Norfolk was resuscitated when the Roman Catholic Church of St John was built in 1910 for Henry Fitzalan Howard, the 15th Duke of Norfolk. It was designed by George Gilbert Scott Jnr (and finished by his brother John Oldrid Scott). From its vantage point on the site of the old city gaol, high on the west side of Norwich, it looks down upon the city much as the ancestral Mount Surrey had overlooked the east side some 360 years before. This fine building, which became a cathedral in 1976, is all lancet windows, built in the Early English style favoured by the duke.

Old maps show one final, tantalising trace of the C17 Howards – My Lord’s Gardens – but I’m reserving that for the next post on Norwich pleasure gardens.

© 2018 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Howard,_3rd_Duke_of_Norfolk

- William A. Sessions (1986). Henry Howard, the Poet Earl of Surrey: A Life. Pub: OUP.

- http://www.classical-music.com/article/quick-guide-talliss-spem-alium

- https://www.overgrownpath.com/2005/05/tallis-forty-loudspeaker-motet.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duke_of_Norfolk

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Howard,_6th_Duke_of_Norfolk

- Francis Blomefield (1806). An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 3, the History of the City and County of Norwich, Part I (London), British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-hist-norfolk/vol3.

- Frank Meeres (2011). The Story of Norwich. Pub: Phillimore & Co Ltd, Andover.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/01/15/the-norwich-coat-of-arms/

- Ernest A. Kent (1932). The Houses of the Dukes of Norfolk in Norwich. Norfolk Archaeology vol XXIV.

- L.G. Bolingbroke (1921). St John Maddermarket: its Streets, Lanes and Ancient Houses, and their Old-time Association. Norfolk Archaeology vol XX.

- http://hbsmrgateway2.esdm.co.uk/norfolk/DataFiles/Docs/AssocDoc6824.pd

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/07/15/the-bridges-of-norwich-1-the-blood-red-river/

- John Kirkpatrick (1889). The Streets and Lanes of the City of Norwich. Pub: Agas H. Goose.

- http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?TNF1521-Norwich-Duke%27s-Palace-Bridge—James-Stark-(Archaeology-and-Art)

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East, page 284. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Howard,_8th_Duke_of_Norfolk

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/sta.htm

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/06/15/norwich-knowledge-libraries/

Thanks to: Clare Everitt at Picture Norfolk for permissions to use images from the superb collection of old photographs of Norfolk from Picture Norfolk. Visit: www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

Fascinating, thank you . Kept me gripped through a long post office queue!

LikeLike

Thank you Deidre. The January post (in the blog sense) should be much shorter.

LikeLike

Excellent blog on the Dukes of Norfolk. Next to the old Library in Duke Street was the Duke of Norfolk pub which in my young days seemed to be the only secular connection with the Cit,y though I believe some land in South Norfolk still belonged to him at that time. Keep up the good work – you deserve an honorary Norfolk passport (temporary of course)

Don Watson

LikeLike

Hi Don, Unfortunately, I didn’t have space for the Duke of Norfolk pub. I did read that people seeking work would be ‘on the palace’: lining up against the wall of the chapel, next to the pub, to advertise their availability for work. Do you know anything about that? And I’ll take that Norfolk passport, thank you, considering the difficulties we’re likely to face in a few months’ time.

LikeLike

I must admit I have not heard of being ‘on the palace’ though when I was young being out-of-work was not something people talked about. Between the pub and the river was an opening with rather tatty buildings down the river side which formed until the late 1940’s the city terminus of the 86 & 87 buses from Upper Hellesdon.

LikeLike

Such an enjoyable read, Reggie! Thank you so much for enlivening this post-Christmas Sunday evening.

LikeLike

Thank you for the kind words Clare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Plains of Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Very informative article. I wish someone could prove or disprove my ancestor’s connection to this line of Howard’s. It has apparently been hotly debated for a couple of hundred years and is still a mystery. Matthew Howard c.1609

LikeLike

Fascinating to have a possible connection to the Dukes of Norfolk. How far back (or forward) can you trace that ancestry? Reggie

LikeLike

Matthew came to Virginia in the early 1600s. Possibly 1620s but thought 1630″s. He had land grant around James River and later was exiled with the independents to Maryland. Apparently he did not stay in MD but his children all took up land patents on the Severn River around Annapolis. Even down to my grandmother, Prudie Howard Bright, we have many of the names used a lot-Phillip, John etc. Three of my granny’s brothers were William, Henry and Thomas.

LikeLike

Pingback: Sculptured Monuments | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Gothick Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

If you enjoyed “Spem” in Janet Cardiff’s installation I think you will blow your mind to a live performance! I’ve sung it a few times over the years, most recently in Holy Trinity, Stratford upon Avon. We were probably doing something right as, so far as I’m aware, William Shakespeare didn’t get up and walk out! As the forty singers are organised in eight choirs each of five voices (SATBB) and the polyphonic entries gradually move around the whole ensemble, the audience in the middle gets the fully immersive effect Tallis intended without moving a muscle. The two moments in the motet where all forty voices sing together is life-changing, even when you know what’s coming up! One theory is that the piece was written for the octagonal Banqueting Hall at Nonsuch, then owned by the Arundel family. This had a gallery all the way round at first-floor level. Of course, I couldn’t for the life of me think of an octagonal space in Norwich with a gallery at first-floor level that might suit a performance of “Spem in Alium”. Peter Phillips recorded it with the Tallis Scholars in Merton College Chapel, but many of their recordings back in the day were made in St. Peter and St. Paul’s at…… Salle! MGR.

LikeLike

Hearing Spem in Allium through 40 speakers was quite something so I can only imagine the blast from 40 live voices. After Tallis I was motivated to dig out Striggio’s Mass for Forty Voices. Tallis shades it.

LikeLike