The northern mill towns that had put Norwich’s centuries-old textile industries out of business celebrated their new prosperity in a Victorian campaign of civic building that passed our city by. In the 1930s, by the time Norwich got around to replacing the medieval Guildhall, the city had reinvented itself as a centre of light industry that could advertise its modernity, not with Town Hall Gothic or Georgian Classical, but with the clean lines of Scandinavian Art Deco. This made Norwich City Hall “the foremost English public building of between the wars” [1] – the figurative roundels on its bronze doors providing a snapshot of Norwich in this inter-war period.

In 1934, James Woodford had designed magnificent bronze doors for the Royal Institute of British Architects headquarters in London …

James Woodford’s bronze doors for the Royal Institute of British Architects at 66 Portland Place London1934 ©RIBApix

… and was subsequently commissioned to design three pairs of bronze entrance doors for Norwich City Hall [2]. Unveiled in October 1938 the 18 roundels – three per door – paid homage to history, trade and industry.

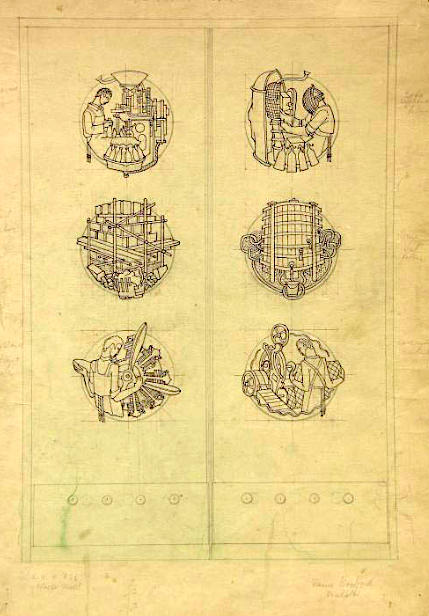

James Woodford’s design for the left-hand side pair of doors. ©Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service

Roundel 1A.Bottling wine *[The three pairs of doors are numbered 1-6 and the three roundels on each door are labelled A-C, downwards].

Incidentally, all 18 of Woodford’s designs are repeated – albeit in a simplified form and without the Art Deco influence – around the top floor of Chapelfield Mall (2005).

Coleman & Co Ltd – not to be confused with Colman’s of mustard fame, who took them over in 1968 – bottled wine that arrived in tankers from various European countries. The factory on Westwick Street/Barn Road occupied a large area centred around Toys R Us (but even this landmark closed in 2018) [3]. Another first for Norwich: Coleman’s were the first company in the UK to make wine-in-a-box. From the 1880s Colemans also made Wincarnis, the name describing a mixture of fortified wine and carne, meat, from a time when this pick-me-up contained beef stock.

From, The Museum of Norwich at the Bridewell

![Coronation Westwick St Wincarnis works [1623] 1937-05-13.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/coronation-westwick-st-wincarnis-works-1623-1937-05-13.jpg?w=654&h=925)

The Wincarnis Works in Westwick Street 1937, destroyed by the Luftwaffe in an incendiary attack 1942 ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

Wine being bottled and labelled by hand, not by a man in a cap as in the roundel, but by female workers at Coleman & Co Ltd. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk.

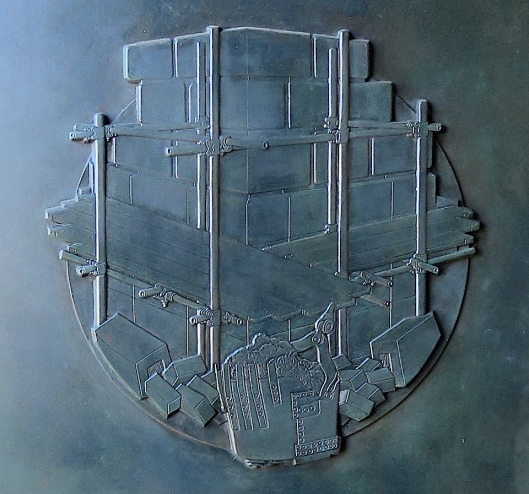

Roundel 1B illustrates building the base of the City Hall using blocks of stone with rusticated (set-back) edges. Incidentally, when buying a suit (a rare occurrence) in London the shop assistant told me that his grandfather, a master mason, travelled to Norwich each week to help build the City Hall.

Roundel 1C. The city’s aeronautical industry

This roundel celebrates one of our largest industries of the time, mainly based around Boulton and Paul’s engineering works on Riverside where they made aeroplane parts. B&P were used to making prefabricated structures like sheds and bungalows; in 1915 this led them being awarded government contracts to build planes [4]. The roundel also acknowledges another Norwich firm, formed by Henry Trevor and his step-son John Page. Trevor, Page & Co. had made furniture since the 1850s and in WWI were contracted by the government to make wooden propellers.

Staff of Trevor, Page & Co (registered at Upper King Street) with two wooden propellers. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

Trevor is perhaps best known locally for his transformation in the 1850s of a disused quarry on Earlham Road into the wonderful Plantation Garden.

Henry Trevor’s Plantation Garden on Earlham Road https://www.plantationgarden.co.uk/

The planes were assembled and tested by Boulton & Paul on Mousehold Heath, which became Norwich Municipal Aerodrome in 1933.

One of Boulton and Paul’s hangars on Mousehold Heath. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk.

The Municipal Aerodrome was opened in 1933 by the Prince of Wales who inspected a flight of B&P’s medium bomber, the Sidestrand – a twin engined biplane.

The Sidestrand. Picture: Ian Burt

Towards the end of WWI, the Sopwith Camel became the country’s most successful fighter (and 50 years later Snoopy’s biplane of choice). Boulton & Paul are said to have made more Sopwith Camels than any other company. Here is the production team with what may well have been one of their last Camels.

Courtesy Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

In 1936, at about the time that Woodward was designing the City Hall doors, Boulton and Paul’s aeroplane division moved to Wolverhampton [4] leaving the old aerodrome to become the Heartsease housing estate. In 1971 the old RAF Bomber Command airfield at Horsham St Faith was redeveloped as Norwich Airport.

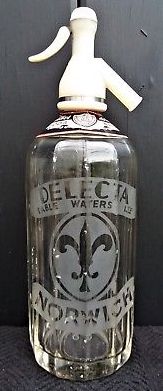

Roundel 2A: the filling of soda siphons.

Each of the big four Norwich breweries (Bullards, Youngs Crawshay & Youngs, Morgans, and Steward & Patteson) marketed their own soda siphons. In addition, Caley’s produced table waters from 1862, which were its main product until they began manufacturing drinking and eating chocolate some 20 years later [5]. Caley’s Fleur-de-Lys works in Chapelfield, which was destroyed in the Baedeker raids of 1942, was rebuilt only to be demolished in 2004 to make way for the intu Chapelfield shopping mall. For a few years, from 1958, Caley’s marketed their table waters under the Delecta brand.

Delecta soda siphon Norwich ©picclick.co.uk

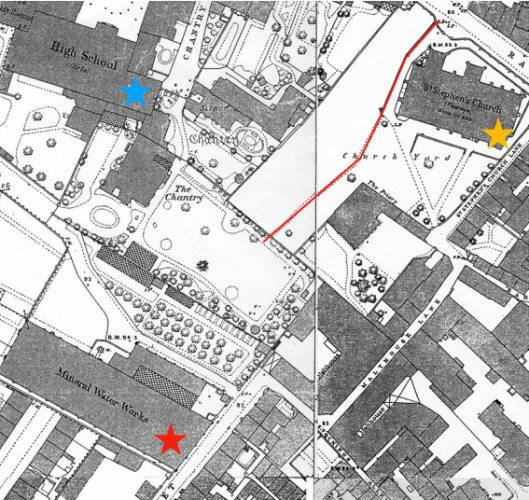

The Mineral Water Works (red star) was situated inside what is now the Theatre Street entrance to Chapelfield Mall.

Red star = Caley’s Mineral Water Works; Blue star = Assembly House (formerly the Girls’ High School; Yellow star = St Stephen’s Church. The red line = the walk through St Stephen’s Churchyard. 1885 OS map hosted by norwich-yards.co.uk courtesy of georgeplunkett.co.uk

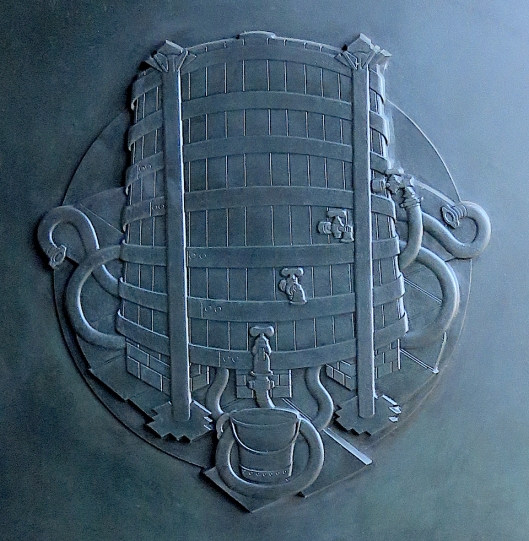

Roundel 2B. The brewing industry.

Although Norwich is famed for having so many medieval churches, this number (‘one for each week of the year’) was dwarfed in the late C19 by 655 licenced houses, far more than the well-rehearsed ‘and one for each day of the year’ [2]. Most of these were eventually brought under the umbrella of the big four Norwich breweries; all, of course, now gone: Bullards on Anchor Quay [2]; Morgans at the Old King Street Brewery – the site now being redeveloped for housing as St Anne’s Quarter; Steward and Patteson’s Pockthorpe Brewery on Barrack Street; and Youngs Crawshay and Youngs on the Wensum Lodge Adult Education site, King Street. Walking down historic King Street today you would never realise it was once home to two large breweries.

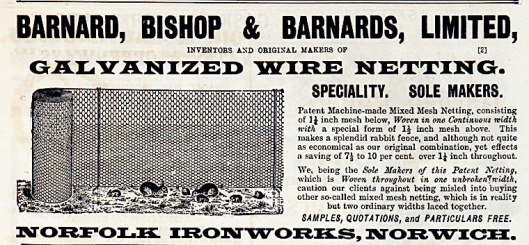

Roundel 2C: Making wire netting.

In 1844 Charles Barnard invented a machine for making wire netting based on weaving looms that would still have been a common sight and sound around the city. His Norfolk Iron Works [see previous post 6] was on the north side of the river, opposite Bullards’ Anchor Quay Brewery.

Charles Barnard’s wire netting loom in The Museum of Norwich at The Bridewell.

The advertisement underlines the point that Barnards were the originators of wire netting and warns against being misled by other brands. Who might they be?

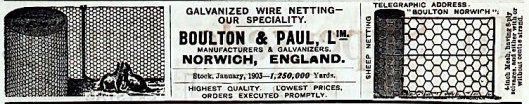

In 1903, Boulton & Paul stocked over 700 miles of wire netting

Across the city, Boulton and Paul were also making wire netting. In WWII – a few years after Woodford designed his roundels – B&P were producing the ‘Summerfeld’ wire-netting track, used as temporary runways for aircraft [7].

Roundel 3A: Building the Castle.

If we had to guess the location of this scene from the scant clothing and hair styles alone we would be excused for placing these men somewhere between the Nile and the Tigris rather than cold old Norwich. This would at least be consistent with Woodford’s Assyrian designs for the two flagpole bases [2] in the Memorial Gardens opposite City Hall where figures ‘walk like an Egyptian’: torso twisted, face in profile.

The roundel illustrates blocks of stone being hoisted up to a building with rounded Norman arches. However, something more efficient than the cranked windlass illustrated here would have been needed to lift large stone blocks (although the treadwheel only seems to have appeared in the mid-C13 [8]). Whatever … it is stone that is being celebrated here for there is none in this desert of flint and chalk, and to raise both castle and cathedral the Norman conquerors imported their own stone at great expense from Caen in Normandy. Norwich Castle was ‘architecturally the most ambitious secular building in western Europe’ [9] and, as the only royal castle in Norfolk and Suffolk, this assertion of Norman power made Norwich the regional capital [10].

Blind arcading on Norwich Castle, which was re-faced with Bath stone in the 1830s

On the roundel we can just make out that the space beneath the rounded arch, which frames the left-hand worker, is filled in with blocks of stone. Such blind arcading is a common decorative element in Norman architecture but the fact that a utilitarian building like the castle has external decoration at all is “remarkable”. As Pevsner and Wilson wrote, “France e.g. has nothing to compare with Norwich” [1]. Hurrah!

Roundel 3B: ‘Historical implements’ [11]

The wool comb on the right is for carding wool; that is, disentangling it and drawing it into parallel fibres ready for spinning the thread. A denser comb with shorter nails would be needed to produce finer yarn used for worsted. Worsted is a smooth cloth without a nap that was particular to Norwich and the surrounding villages (e.g., Worstead); the manufacture of worsted was probably the city’s major industry throughout the late middle ages [12]. The whirligig in the centre is an ‘umbrella swift’ for winding yarn – either silk or wool [13]. The stand on the left holds two yarn winders on which the thread is spooled ready for weaving. The simplicity of these implements emphasises the pre-industrial nature of the early textile business, often conducted in small workshops and attics by family groups [13].

I was surprised that the final object, seen at the bottom of the roundel, was a cobbler’s bench [2] because, surely, Woodford wouldn’t interrupt his textile cycle by including a different trade? Well, there it is at The Bridewell Museum, a turnshoe maker’s bench.

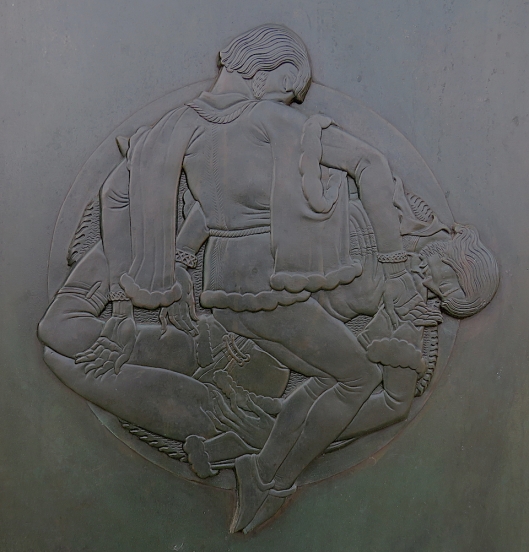

Roundel 3C: The Black Death

According to the historian Francis Blomefield the bubonic plague first arrived in Norwich on January 1st 1348 [14] but it was to return intermittently over the next three centuries. In the years preceding the first outbreak the city’s numbers were swelled hugely by the arrival of land-starved peasants coming in from the country to seek work [15]. The Black Death reduced this jam-packed population by about a third to a half and wasn’t to return to its original level until the late C17 [15]. Bodies were buried in communal pits in the Cathedral Close and the churchyard of nearby St George Tombland; in the Great Plague of 1665-6 Chapelfield was used as a mass grave [16]. High and low were struck down alike.

The last British example of the Dance of Death in stained glass. St Andrews, Norwich ca 1510.

Next month, the other nine roundels

©2019 Reggie Unthank

Contains Photographs of the Unthanks and material not included in the blog. From Jarrolds Book Department or online (click here) and the City Bookshop, Davey Place, Norwich (or click here).

Sources

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- Richard Cocke (photography by Sarah Cocke) (2103). Public Sculpture of Norfolk and Suffolk. Pub: Liverpool University Press.

- http://www.wisearchive.co.uk/story/the-silent-e-in-colemans/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boulton_%26_Paul_Ltd

- http://letslookagain.com/tag/a-j-caley-of-norwich/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/tag/barnard-bishop-and-barnards/

- Boulton and Paul (1947). The Leaf and the Tree: The Story of Boulton and Paul Ltd 1797-1947. Pub: Boulton and Paul.

- https://uccshes.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/medieval-treadwheels-artists-views-of-building-construction.pdf

- T.A. Heslop (1994). Norwich Castle Keep: Romanesque Architecture and Social Context. Pub: Centre of East Anglian Studies, UEA.

- Bryan Ayers (2004). The Urban Landscape. In, Medieval Norwich. Eds Carole Rawcliffe and Richard Wilson. Pub: Hambledon and London.

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/stp.htm#Stpet

- Penelope Dunn (2004). Trade. In, Medieval Norwich. Eds Carole Rawcliffe and Richard Wilson. Pub: Hambledon and London.

- Ursula Priestley (1990). The Fabric of Stuffs: the Norwich Textile Industry from 1565. Pub: Centre of East Anglian Studies, UEA.

- Francis Blomefield’s history of the City of Norwich (1806) available online at: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-hist-norfolk/vol3/pp79-101

- Elizabeth Rutledge (2004). Economic Life. In, Medieval Norwich. Eds Carole Rawcliffe and Richard Wilson. Pub: Hambledon and London.

- http://www.chapelfieldsociety.org.uk/history-of-chapelfield/.

Great post. Not only did Boulton & Paul build Sopwith Camels in WW1, they also built the framework of the R101 and for a time in WW2 B&P Defiants flew from RAF Horsham St Faiths. Wincarnis put their tonic wine in very tasty jellies.I look forward to the next post

Don Watson

LikeLike

Hi Don, I do vaguely remember Wincarnis being advertised in my local chemist. Not so sure about a beef-stock jelly (although that was probably when the formulation was originally made in Germany).

LikeLike

Fascinating post, Reggie. Today’s mission will be to have a closer look at the roundels on site..

LikeLike

Your mission – should you choose to accept it – is to find the two signatures on the roundels. Good luck.

LikeLike

Nicely researched, Reggie. I too, must try to get closer to those doors.

LikeLike

The roundels seem to be hidden in plain sight. I challenge you to find the two signatures on the roundels, Clare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I accept your challenge!

(Actually Clare, there are one or two more signatures hidden around the pieces. Reggie)

LikeLike

As well as Worsted cloth there was also Walsham cloth and a linen from Aylsham known as Cloth of Aylsham or Aylsham Webbs

LikeLike

Hello David, Worsted/Worstead does get the lion’s share of attention but I’ll see if I can give the others important cloth towns a boost.

LikeLike