The Normans left Norwich a magnificently tangible legacy of Castle and Cathedral but traces of their Scandinavian cousins – the Vikings – are harder to find.

Roundel 4A: The Vikings

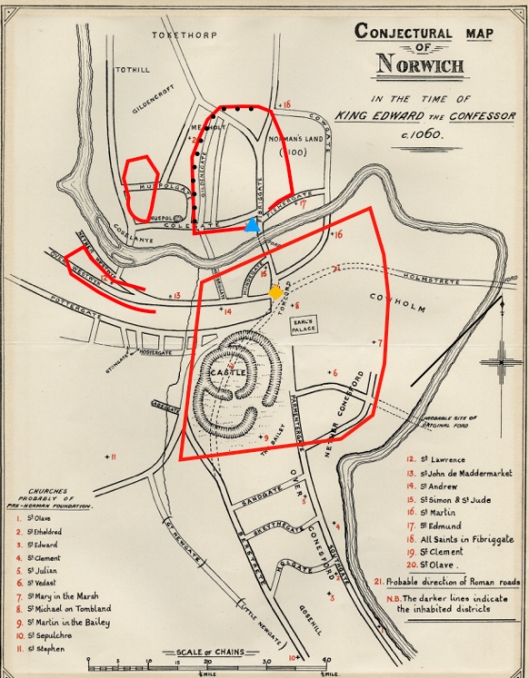

For the first roundel in this ‘second half’ of his plaques on the City Hall doors (1936-8), James Woodford acknowledged the significance of the Viking invasion to the development of proto-Norwich. The Great Heathen Army first invaded East Anglia in 865AD but there is little physical evidence that Scandinavians settled in Norwich until the C10 [1]. Then, there is evidence of an Anglo-Scandinavian settlement – a North wic on the northern side of the Wensum, centred along modern-day Magdalen Street, defended by a looping, 13-foot-deep ditch and probably topped by bank and fence. This may have been constructed in response to Anglo-Saxon pressure from Edward the Elder of Wessex who overcame the East Anglian Danelaw in 9 I 7.

Anglo-Scandinavian Norwich outlined in red. Dotted lines mark the known defensive ditch. Blue triangle = St Clement Colegate; yellow diamond = Tombland marketplace. Map courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service, redrawn from Philip Judge’s map in [1].

This protected settlement was sufficiently important and stable in the C10 to have its own mint making Anglo-Saxon ‘Nordwic’ coins.

Æthelstan, Anglo-Saxon King of Wessex. Penny minted in Nordwic ca 930AD. © CNG 2019

Scandinavian influence can be detected in the naming of churches: St Clement – the patron saint of sailors – was much favoured by the Scandinavians and his churches occur at rivers or portals as here, at St Clement’s on the corner of Fye Bridge Street and Colegate. Norwich also had two churches named after St Olave or Olaf, the Norwegian king canonised in 1030.

St Clement’s Fye Bridge/Colegate, perhaps pre-Conquest, now mostly C15/16

The Anglo-Scandinavian settlement was not confined to the northern bank for it extended southwards to form a double burh joined across the river by a wooden causeway where Fye Bridge now stands [1]. A few hundred yards south of the river was the marketplace in Tombland, from the Danish word täm for open space and it is from their word ‘gata’ meaning street that we have inherited Finkelgate, Fishergate, Pottergate, Colegate, Mountergate etc. What may have caused Nordwic to abscond to the south bank was the raid in 1004 when Sweyn Forkbeard – whose sister Gunhilde had been amongst the hundreds of Vikings killed in the so-called St Brice’s Day Massacre – laid waste to Norwich. When the French descendants of the Vikings – the Christianised Normans – arrived a few decades later they established their presence on the south side with their cathedral of stone and a castle overlooking a re-sited marketplace.

Roundel 4B: Textiles and agriculture

The middle roundels 3B and 4B on the central pair of doors

On roundel 4B Woodford presents us with much the same layout he used on the facing roundel (3B, see previous post): the wool comb could be a mirror image of the comb on the left-hand roundel, there is another yarn winder and, again, a stand – this time a candle holder seemingly warming a tool clamped above (anyone?). Again, an object at the bottom breaks the weaving sequence but here it is not specifically related to Norwich industry but to Norfolk in general. The wheels on this plough reduce friction so that one ox could draw it through the light Norfolk soil and as such the image refers to Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester (1754-1842), who was first to have harnessed rather than yoked oxen. From his Holkham estate on the North Norfolk coast Coke is credited with sparking the British Agricultural Revolution [2].

The Leicester Monument (1845) at Holkham Hall, in memory of the 1st Earl. Between the wheeled plough and the ox are sheep, referring to the ‘English Leicester’ – an improved breed promoted by Lord Leicester. © racns [3]

Here hangs Robert Kett from the walls of Norwich Castle.

The success of the Norwich weaving trade, and the rising price of wool, led to rich landlords enclosing common land in order to graze their own sheep. In 1549 Robert Kett, a tanner from Wymondham, sided with those uprooting hedges and fences. Under his leadership the uprising swelled to about 15,000 ‘rebels’ encamped on Mousehold Heath. Kett’s men defeated forces led by the Marquess of Northampton but were finally overcome at the Battle of Dussindale. Robert Kett was hanged from a gibbet erected on the battlements of Norwich Castle and “left hanging, in remembrance of his villany, till his body being consumed, at last fell down”. His brother was left hanging by chains from the steeple at Wymondham [4]. The C18 historian Francis Blomefield wrote that Kett’s army contained the ‘scum of Norwich’ but, of course, one man’s rebel is another man’s freedom fighter and a plaque on the castle walls expresses a more enlightened view:

In 1549 AD Robert Kett yeoman farmer of Wymondham was executed by hanging in this castle after the defeat of the Norfolk Rebellion of which he was the leader.

In 1949 AD – four hundred years later – this memorial was placed here by the citizens of Norwich in reparation and honour to a notable and courageous leader in the long struggle of the common people of England to escape from a servile life into the freedom of just conditions.

Roundel 5A: Chocolate and crackers

We know this represents Caley’s, rather than other confectioners, because of the combination of chocolate-making and Christmas crackers that we see arranged around the perimeter of this roundel. Twelve years before James Woodford drew this design Caley’s installed 44 chocolate-piping machines [5] so the worker is piping chocolate in their Fleur-de-Lys Factory in Chapelfield.

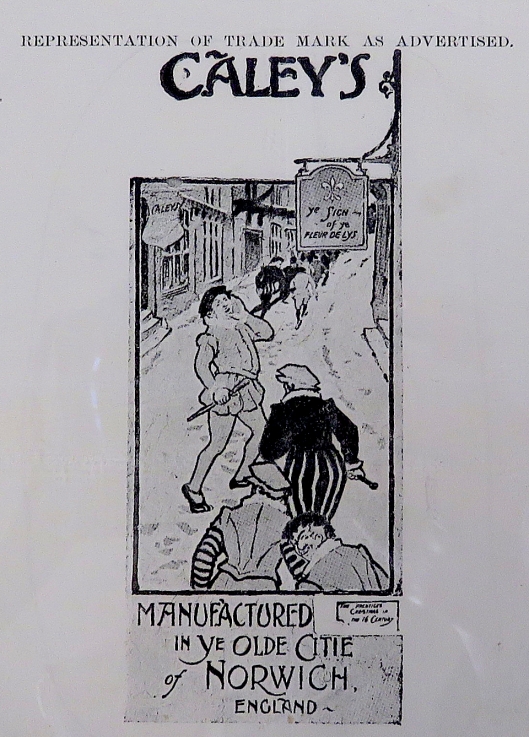

Registration of Caley’s trade mark ‘The Prentices Christmas in the Snow’ (1899). Note ‘Ye Sign of ye Fleur de Lys’. Courtesy Norfolk Record Office BR266/119/2

Between the 1864 and the 1883 editions of Kelly’s Directory, chemist and druggist Albert Jarman Caley – ‘manufacturer of aerated & mineral waters, & ginger ale’ – had moved from London Street to Chapelfield (1883), presumably to take advantage of a nearby deep well with the purest water in the city [7]. His sodas were bottled in an old factory in Chapelfield that had made cloth for glove-making but this was just the beginning of Caley’s expansion.

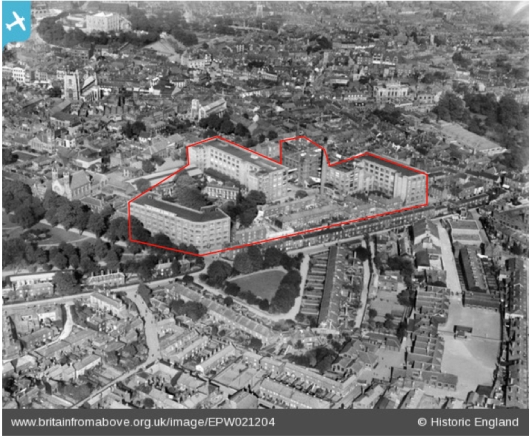

Caley’s Fleur de Lys works 1928 now the site of Chapelfield shopping mall. Chapelfield Gardens are to left and, below, is the triangle of The Crescent where Alfred Caley lived

In order to provide year-round employment for his summer workforce, Caley started to make drinking chocolate in 1883 and three years later began to make chocolate confectionery using milk from a farm in nearby Whitlingham [6]. In 1932 Caley’s was sold to Mackintosh’s, the toffee-makers from Halifax, who modernised the factory and produced new lines, like the chocolate-toffee combos ‘Rolo’ and ‘Quality Street’ assortment. The factory was rebuilt after being badly damaged in the 1942 Baedeker Raids. In 1969 the business was acquired by Rowntree’s and then by Nestlé (1988) who sold the site to be redeveloped as intu Chapelfield shopping mall (2005). Have I mentioned the aroma of chocolate over the city, usually – it seemed – on Sunday mornings?

This stone roller once used for grinding cocoa beans is now used as a seat at the Chapelfield Road entrance to the intu Chapelfield mall where Caley’s once stood

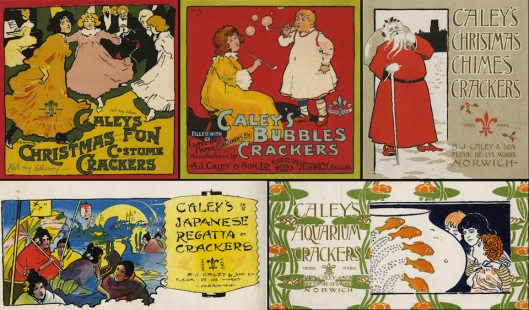

In 1899 the Caley’s fancy box department expanded into making Christmas crackers – some of the boxes decorated by a young Alfred Munnings who had recently graduated from the Norwich School of Art. Tom Smith, inventor of the Christmas cracker [8], opened his factory on Salhouse Road in 1953, too late to be considered an influence on Woodford’s roundel.

Caley’s Christmas cracker boxes ca 1900. Some, such as the first two, bear Munnings’ signature. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collections

Roundel 5B: Livestock markets

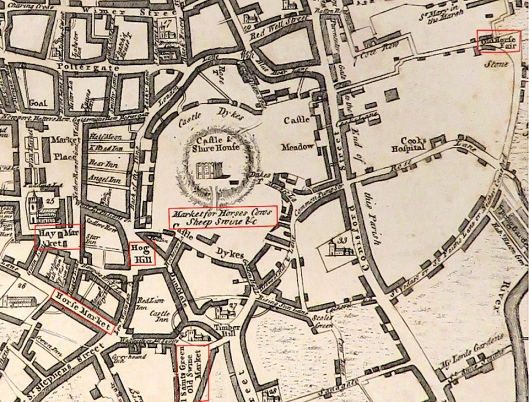

Norwich was the trading centre for a major agricultural county and, since at least the time of James II, livestock was brought to the Castle Ditches or Dykes for sale [9]. The ‘Market for Horses Cows Sheep & Swine’ is clearly marked on King’s C18 map. Also marked are Old Horse Fair, Haymarket, Hog Hill (Orford Hill near the Bell Hotel), Horse Market (now Rampant Horse Street) and the Old Swine Market on All Saints’ Green – all contributing to a sense of the city as a hub for the county’s agriculture.

Samuel King’s New Plan of Norwich 1766. Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service

After the coming of the railways, cattle would be driven from Norwich Thorpe Station, up the new, wide Prince of Wales Road to various sites around the castle commemorated in the street names: Cattlemarket Street, Market Avenue, Farmer’s Avenue.

![Cattle Market view NE from Market Avenue [4541] 1960-03-12.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/cattle-market-view-ne-from-market-avenue-4541-1960-03-12.jpg?w=529)

Norwich Cattlemarket from Market Avenue, 1960. This is to the rear of the Agricultural Hall with the cathedral spire just visible, right of centre. Courtesy of http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk

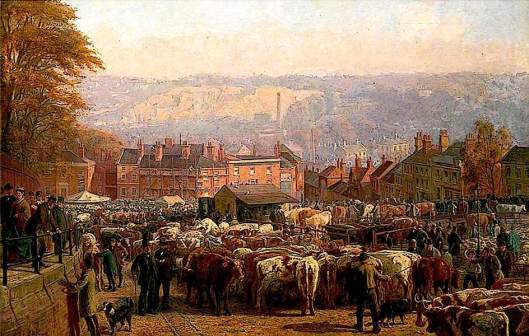

Here we see the Cattlemarket in 1877. Today, this is the site for the garden and glazed roof of subterranean Castle Mall. In 1960 the Cattlemarket was taken out of town to Hall Road.

Sheep sale at the Cattlemarket at a time when the castle was Norwich Prison. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

Roundel 5C: Shoe-making

The City Hall stands on the site of a former Start-rite shoe factory and it is shoe-making that is celebrated in this roundel.

Preparing soles

By the 1840s the city’s textile trade was in decline but the same pattern of work – production by outworkers controlled by garret-masters – was inherited by the city’s rapidly expanding boot and shoe manufacturing trade. Soon, this piecemeal form of production was overtaken by large-scale manufacture in factories. Numerous small businesses became consolidated into the Big Five companies that dominated Norwich’s boot and shoe trade: Edwards & Holmes; Howlett & White (later the Norvic Shoe Co.); Haldinstein’s (later the Bally Shoe Co.); James Southall (later Start-rite); and H. Sexton & Sons (later Sexton, Son & Everard). About the time that Woodford was designing this roundel the Norwich boot and shoe trade was employing about 10,000 workers, although none of the major factories are operating now [10, 6].

The former Norvic Shoe Co at the corner of St George’s Street and Colegate was once the biggest shoe factory in the country

Roundel 6A: Soldering mustard tins

Here, the worker is soldering tins with what appears to be a pool of molten lead; a soldering iron is highlighted on the left. He would have been working on a production line at Colman’s of Carrow, famous worldwide for producing mustard. This company’s yellow tins of mustard powder were emblematic of the city and it is a great sadness that the factory will close in 2019 after over 150 years at the old Carrow Abbey site.

Roundel 6B: More livestock

This image is paired with the ‘livestock’ roundel on the facing door (5B above).

The Hill at Norwich on Market Day, by Frederick Bacon Barnwell (1871). Looking down Cattlemarket Street at the ‘back’ of the Castle, separating into Market Avenue to the left and, to the right, down Rose Lane to a distant Thorpe Hamlet

Roundel 6C: Silk weaving

This plaque almost certainly refers to the firm of Francis Hinde & Hardy who employed several hundred people in St Mary’s Works on Oak Street [6].

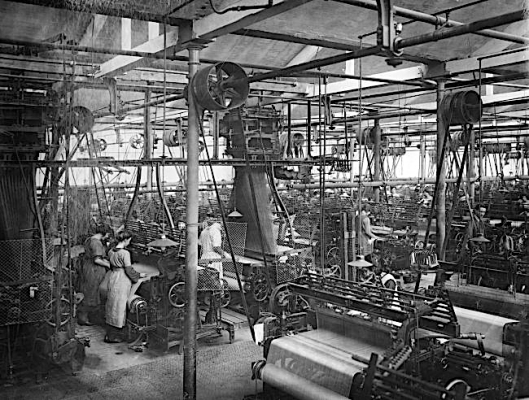

Silk weaving at Hinde’s St Mary’s Mill at Oak Street. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

In the 1550s and 60s Dutch and Belgians Protestants fleeing from religious persecution settled in Norwich, eventually comprising a third of the city’s population. These ‘Strangers’ revived our flagging textile trade and helped develop New Draperies that included silk. Even in the C19, when the textile trade was in serious decline, Norwich silk shawls and ‘Mourning Crape’ kept business alive [11]. In the 1920s Hindes expanded, taking over other Norwich silk weavers and building a silk-weaving mill at Mile Cross; they also owned another silk mill at Oulton Broad. In the 1920s and 30s Hindes were experimenting with nylon and an artificial silk (Rayon) so the roundel may depict the weaving of artificial yarn [12]. Later, Hindes’ produced parachute fabric in WWII.

1949 advertisement. Courtesy [13]

In 1964 Hindes was bought by the giant Courtaulds; the factory closed in 1982, ending 700 years of textile manufacture in the city [6].

The 19th roundel

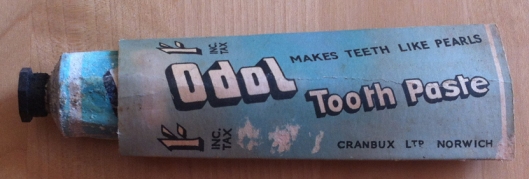

For the final – the 18th – roundel, Woodford chose to illustrate silk weaving but his designs indicate that his original intention was to show tubes being filled with toothpaste [3]. I did read that the toothpaste was ‘Odells’ but it turns out to have been ‘Odol’ by Cranbux Ltd of 103 Westwick Street – a firm owned by Coleman & Co Ltd [14]. Remember Coleman’s (with an ‘e’), the wine-bottling company from Westwick Street that we saw on roundel 1A?

When Norwich had its own toothpaste. ‘Odol’ marketed by Cranbux, owned by Coleman & Co Ltd, Norwich. Photo courtesy of atlasrepropaperwork.com [14]

We have to ask whether these roundels gave a fair reflection of the city. Well, it’s rather puzzling why Woodford even considered the filling of toothpaste tubes when he could have chosen the famous home-grown insurance business, Norwich Union (now Aviva). Woodford’s vision was decidedly backward-looking but who in 1936 anticipated the war and could imagine what post-war life would be like in a post-industrial Britain? Now, Norwich is a city of literature and science, amongst many other things, but it would take a brave person to commission another set of roundels to fix this moment in time.

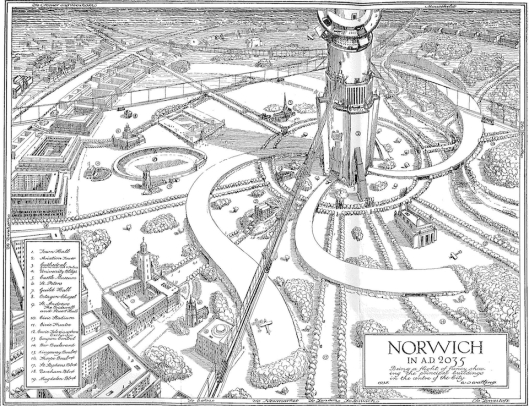

(That was to have been my ending but, serendipitously, I came across someone who did have the courage to predict the city’s future. In 1935 an Art Master at CNS School, Walter Watling, drew ‘Norwich in AD 2035’. In his prophetic dream he was introduced to someone over the “televisophone” who “promised to send along the glasses and in another minute they arrived by the pneumatic tube delivery service [15].” Quite a good stab at the smartphone and Amazon, no?)

‘Norwich in AD 2035’ by WT Watling [15, 16].

©2019 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- Brian Ayers (2004). The Urban Landscape. In, Medieval Norwich (Eds Carole Rawcliffe and Richard Wilson. Pub: Hambledon and London.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Coke,_1st_Earl_of_Leicester_(seventh_creation)

- http://racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp?action=getsurvey&id=6

- Francis Blomefield (1806). ‘The City of Norwich’ Ch 25, online at: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-hist-norfolk/vol3/pp220-265

- Norfolk Record Office BR266/93.

- Nick Williams (2013). Norwich: City of Industries. Pub: Norwich Heritage Economic and Regeneration Trust.

- Barry Pardue (2005). Norwich Streets. Pub: Tempus.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christmas_cracker

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/markets.htm

- Frances and Michael Holmes (2013). The Story of the Norwich Boot and Shoe Trade. Pub: Norwich Heritage Projects.

- Gillian Holman (2015). Made in East Anglia: A History of the Region’s Textile & Menswear Industries. Pub: The Pasold Research Fund http://www.pasold.co.uk/download/%7BA14AC35B-4095-46E1-BBB9-F54A05D5DA92%7D/made-in-east-anglia

- Communication from Cathy Terry, Senior Curator at Strangers’ Hall Museum, Norwich.

- https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Francis_Hinde_and_Sons

- https://www.atlas-repropaperwork.com/odol-toothpaste/#comment-22921

- Walter T Watling (1935). ‘Norwich AD 2035: A Prophetic Fantasy’. In, The Norwich Annual 1935.

- https://www.edp24.co.uk/features/remembering-scatty-an-art-master-with-a-future-vision-1-5894702

Thanks: to Cathy Terry of the Strangers’ Hall Museum for information on silk weaving; Cathy acknowledges the research of Thelma and Alan Morris. I am grateful, as ever, to Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk for permission to reproduce images. I also thank Derek James of the Eastern Daily Press for kindly sending me the Watling illustration. See his article on Walter Watling in [16].

Love you Reggie-brilliant.

LikeLike

Gosh. Thank you Daniel.

LikeLike

Fascinating article a real eyeopener. Well done Reggie!

LikeLike

Appreciate the kind words Theo. Thank you.

LikeLike

The detail in these roundels is amazing! I haven’t yet been able to get to the city to admire these close-up. Thank you for all your research and the fascinating post, Reggie.

LikeLike

The roundels are great, aren’t they, Clare? A wonderful, if unsung, example of public art.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As ever brilliant reading, providing an enlightening interlude and I’ll be off to explore both the doors and areas mentioned with fresh eyes over the coming weeks. Keep up the great work Reggie.

LikeLike

I’m pleased you liked the post, Kassie. Let me know how you get on with the tour. Reggie

LikeLike

Another splendid post. I must visit the third floor of the Chapelfield Mall again to compare the stylised versions with the originals. Great bit about the vision of 2035 Norwich!

Don watson

LikeLike

Hi Don, The Chapelfield roundels are best seen from the main arcade second floor. Interesting that Woodford’s work was chosen for another run out here. Reggie

LikeLike

I came to this later than usual but what a feast – thank you!!

LikeLike

Thank you Heather

LikeLike

Thank you for another great post, thank you.

LikeLike

Glad you liked it Paul, Reggie

LikeLike

Fantastic article. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you. Good luck with the gardening, now that spring is here.

LikeLike