Tags

catherine maude nichols, Norfolk and Norwich Art Circle, Norwich School of Artists, The Woodpecker Club

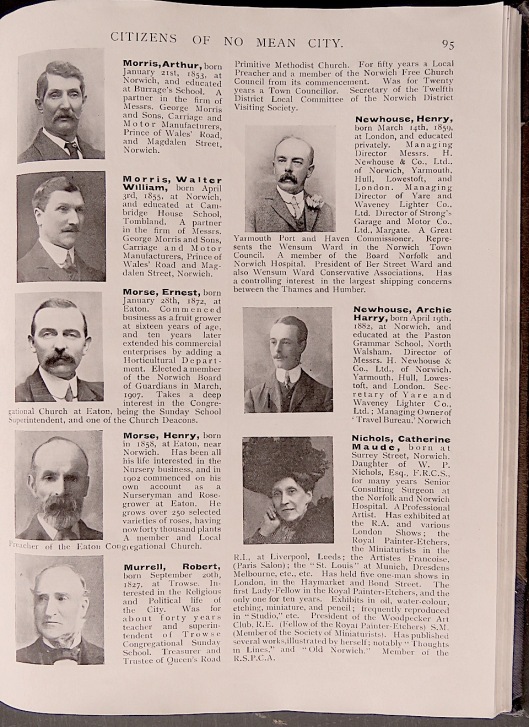

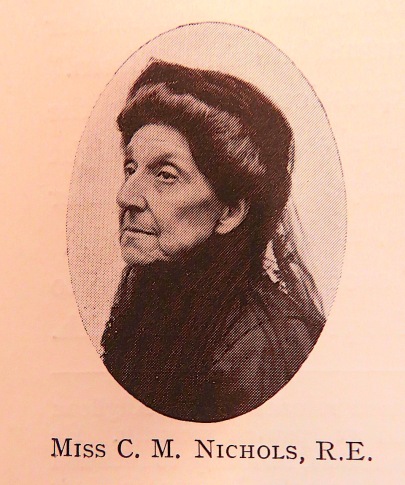

I first came across Catherine Maude Nichols in a book published in 1910 called ‘Citizens of No Mean City’, a Jarrolds trade book containing over 360 potted biographies with accompanying photographs of ‘Norwich Citizens of To-day’ [1], some of whom probably paid for advertising their business on the facing page. I was attracted by the fact that Kate Nichols was one of only three women … and by the flamboyant hat.

Although she herself was not a major figure her artistic life is fascinating for spanning the last days of Crome and Cotman’s Norwich School of Artists and the emergence of English Impressionism.

From [1]

Kate was born in 1847 behind this fine Georgian doorway at 32 Surrey Street, Norwich, where she was looked after by a nanny and a nurse.

![Surrey St 32 Regency Georgian doorway [0468] 1935-04-19.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/surrey-st-32-regency-georgian-doorway-0468-1935-04-19.jpg?w=529)

The Regency doorway at 32 Surrey Street ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

This was on the opposite side of the street to the tall terrace, built in 1761 by Thomas Ivory (Assembly House, Octagon Chapel), where Sir James Edward Smith of Linnean Society fame lived from 1796 to 1828 [see previous blog post 2]. Unfortunately, this fashionable Georgian street was bombed in WWII and the even-numbered houses on the east side no longer exist. Fortunately, George Plunkett recorded No 32 in 1935.

![Surrey St 30 to 34 [1028] 1936-06-14AA.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/surrey-st-30-to-34-1028-1936-06-14aa.jpg?w=529)

30-34 Surrey Street 1935. ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

Kate Nichols’ father was born into a wealthy Norfolk farming and landowning family who lived at Alpington Hall, a few miles south of Norwich [3].

Alpington Hall. ©Evelyn Simak. Creative Commons

Her father, William Peter Nichols, was related to the Musketts. Regular readers may recall that when Colonel C. W. Unthank married Mary Anne Muskett and moved into her family home at Intwood Hall, a few miles south of the city, he started selling off his own land on which much of Norwich’s present-day Golden Triangle was built [4].

Kate’s father trained in London as a surgeon and returned to Norwich in the 1820s. In the 1850s he was appointed one of the four surgeons at the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital where he specialised in removing bladder stones – something once common in Norfolk.

The north-east wing of N&N Hospital, built by Thomas Ivory’s son William in the 1770s. Most of Ivory’s hospital was rebuilt by Edward Boardman 1879-1884 [5].

At various times William Peter Nichols was to be mayor and local magistrate as well as surgeon to the police, to the prison and to the Bethel Hospital. The latter was opened in 1713 by Mary Chapman as an asylum for the curable mentally ill and may well have been the first purpose-built asylum in the country. In 1836 Nichols bought Heigham Hall as a ‘private lunatic asylum’ for ladies and gentlemen. We previously encountered this mansion at the junction of Old Palace Road and Heigham Street when trying to discover which of several Heigham Houses/Halls was home to the Unthank family [6]. This mental asylum was in competition with the genteel Heigham Retreat whose tree-lined avenue is commemorated by Avenue Road.

Etching of Heigham Retreat by Henry Ninham ©Norfolk Record Office MC279/6. Avenue Junior School now occupies part of this site.

Nichols and two other doctors bought out Heigham Retreat but closed it in 1859. This was after Heigham Hall had been mired in scandal. In 1852 a curate from Hethersett, Reverend Edmund Holmes, was accused of raping a young girl but, because of his family’s standing in the county, Holmes was promptly admitted to Heigham Hall by Dr Nichols in order to evade arrest. Nichols then appointed Holmes as chaplain to the asylum [7] and boasted that he had rescued one of his class from the clutches of the law [3].

In 1870, Sir Robert John Harvey, senior partner in Norwich Crown Bank on Agricultural Hall Plain, shot himself after bankrupting the business. Hard to believe but in a letter to the Eastern Daily Press dated 1960 the correspondent recalls tales of a suicide being buried with a stake through the heart at a crossroads in Heigham [8]. Although such roadside burial was repealed in 1823 those who committed self-murder whilst still in control of their faculties could only be buried in cemeteries between 9pm and midnight, and without ceremony. William Nichols was the Harvey family’s doctor and it was his diagnosis of hereditary ‘excitement’ (i.e., whilst the balance of his mind was temporarily disturbed) that allowed Sir Robert a Christian burial.

Norwich Crown Bank on Agricultural Hall Plain. After the Harvey affair the goodwill and building were bought by Gurneys Bank, the forerunner of Barclays.

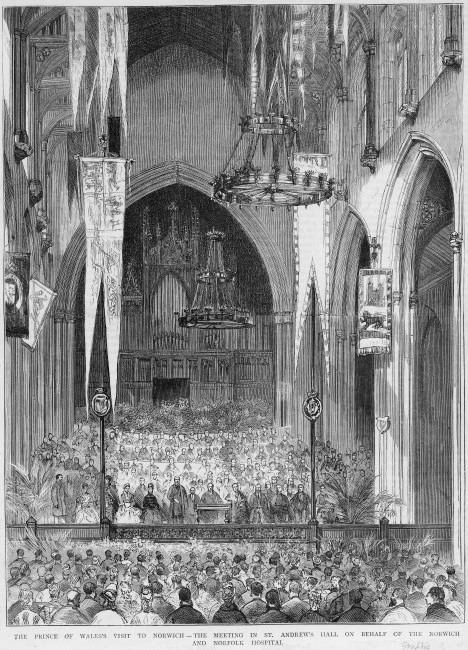

It was into this wealthy and politically involved family that Kate was born. And when, in Dr Nichols’ mayoral year (1866), the Prince and Princess of Wales visited Norwich together with the Queen of Denmark it was Kate who presented the princess a book of Norwich photographs on behalf of the women of the city [7].

The royal party at the music festival held at St Andrew’s Hall in aid of the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital ©Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

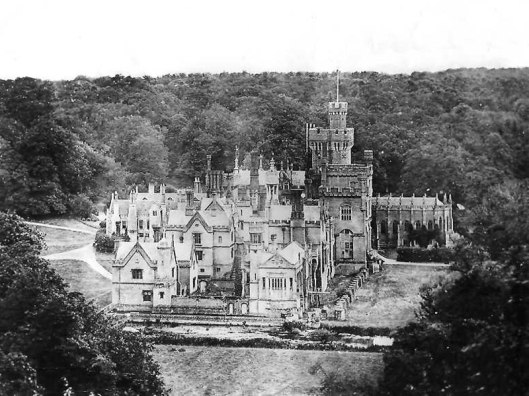

That evening Kate accompanied her parents to a ball held at Costessey Hall where the royal party stayed for three days with the Jerninghams in their never-completed Gothic fantasy.

Costessey Hall. A C19 Neo-Gothic fantasy made of Gunton Bros ‘fancy bricks’ from the nearby Costessey Brickworks [9].

Costessey Hall was made of ‘Cossey’ brick, baked from Jerningham clay by the Gunton family who went on to supply decorative and carved bricks that can still be seen around the city [see previous post 9].

Guntons’ Tudorbethan chimneys on a house in Chapelfield North

There seems to have been something Walter Mitty-like about Kate Nichols. She was to describe herself as a spinster with no close relatives but in so doing she ignored two brothers, three nieces, two nephews and a dozen cousins [3]. She would also tell others that she was a self-taught artist despite: having a drawing mistress at school; studying with David Hall McEwan, a member of the Royal Society of Watercolour Artists; and at age 27 studying for two terms at the Norwich School of Art where she probably learned etching and won a prize in the Advanced Division. Indeed, the Head of the NSA stated that Kate Nichols and George Skipper were the two best students during his 25-year tenure [3].

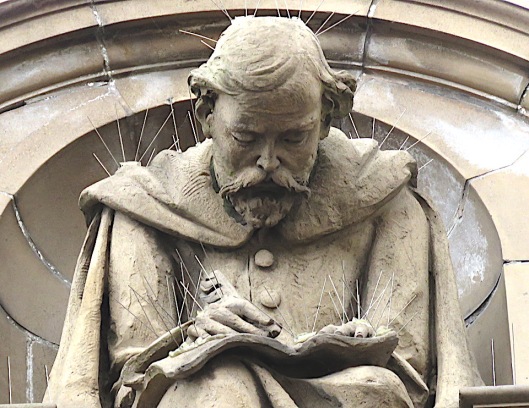

Not recorded as such but this is an excellent likeness of George Skipper, Norwich’s flamboyant architect, sitting on top of his Commercial Chambers in Red Lion Street [see 10].

There was an artistic strand in the Nichols family for her four aunts had been taught at Alpington Hall by co-founder of the Norwich School of Artists, John Crome, some of whose landscape paintings hung in Kate’s home in Surrey Street [3].

Almost always described as ‘etchings’ most of Kate’s output was actually dry point engraving. Unlike etching, which involves ‘eating’ into a copper plate with acid, dry point engraving involves incising lines directly onto a copper sheet with a sharp tool; this raises a ‘burr’ that – when inked – is pressed onto paper to create an impression. Because printing produces a mirror image the original scene should be drawn in reverse but for some reason Kate did not do this for ‘Tombland’.

Left: Tombland Alley with the house of Augustine Steward, which was used by Royalist troops during Kett’s Rebellion of 1549. Right: ‘Tombland’ drypoint by CM Nichols courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

Kate’s first dry point engraving for which there is a record, ‘College’, was made in 1875 when she was 28. There was something about this linear technique that suited Kate’s fondness for landscape for she seems to have been less accomplished with the rounded forms of the human body [3].

‘College’ (which appears to be St John’s Cambridge) 1875. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM : 1969.557.63

Here we see the gardens of the Bethel Hospital, where her father was surgeon.

Dry point and oil painting of the Bethel Hospital. Undated but after 1882. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collections. NWHCM : 1940.75.19 and NWHCM : 1940.75.8

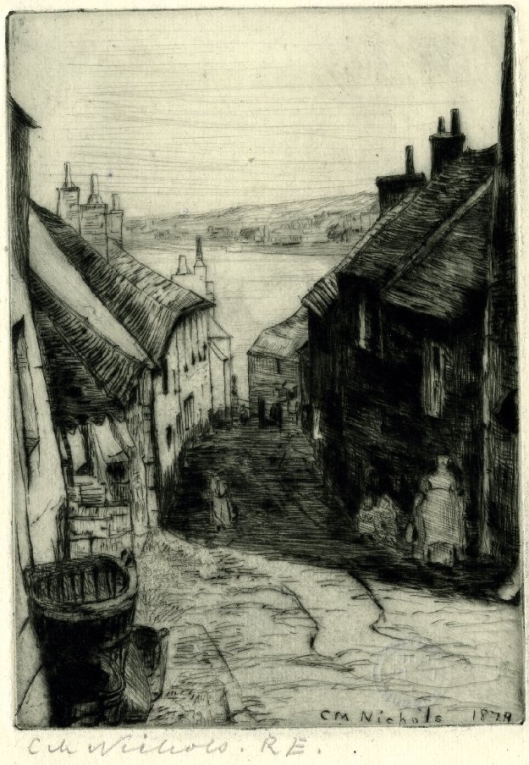

Kate Nichols was single and adventurous, dropping in – apparently – on artists she admired, such as Lord Leighton and John Everett Millais [3]. She travelled alone to France and from 1876-8 visited Barbizon, south of Paris, to join others painting there. This was a generation after the original founders of the Barbizon school, such as Corot and Millet, had painted landscape from nature in the manner of East Anglian John Constable. Future Impressionists like Monet, Renoir and Sisley also went to Barbizon and although Kate may not have met them she at least mixed with ‘hundreds of artists’ who were also paying their dues [3]. In 1879, she stayed in Newlyn – the Cornish counterpart to Barbizon – and this time she was not too late to catch the wave: now she was amongst painters out of whom the ‘Newlyn Group’ of artists would emerge with their impressionistic style.

Old Houses, Cornwall 18979 ©The Trustees of the British Museum

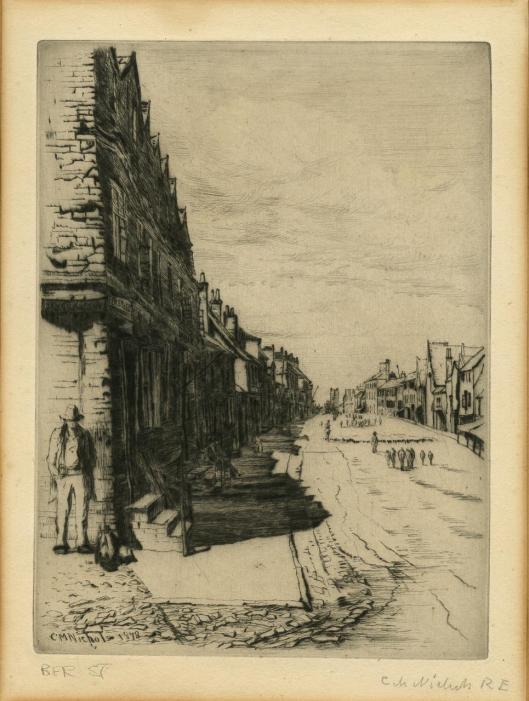

Back home, Kate was to draw from the countryside around Norwich as well as the urban landscape of the city itself. She exhibited widely and between 1877-1908 some of her engravings were shown at the Royal Academy. The first was of Ber Street, Norwich, which illustrates animals being driven towards the livestock market around the castle.

Ber Street 1878 ©Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Kate was influenced by the Norwich School painters whose work had hung in her family home [3]. In 1907 she was to produce a folder of prints entitled ‘After Crome’.

Left: ‘The Poringland Oak’ (1880-1820) by John Crome. The Tate, Creative Commons Licence. Right: ‘Poringland Oak (After Old Crome)’ by CM Nichols. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

Oil painting ‘Old Norwich River’ by CM Nichols (her drypoint of this scene is labelled ‘Widdow’s Ferry’. Could this be Pull’s Ferry since Pull married Widow Sandling and took over Sandling’s Ferry?). Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM 1952:125

She was obviously fond of the area around Cow Hill.

Left: Drypoint of Cow Hill 1883, exhibited at The Royal Academy and reproduced in The Studio; courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk. This looks up to great St Giles with the morning sun spilling down from Willow Lane.

The houses in Willow Lane, off Cow Hill, are largely as Kate must have seen them, though not all of the houses on Cow Hill survive.

Left: Willow Lane by CM Nichols. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

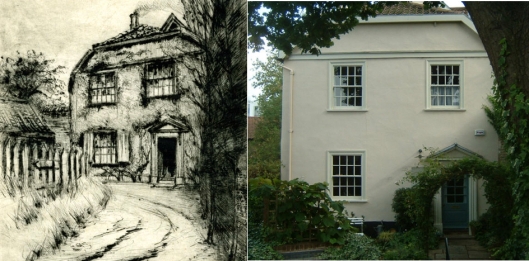

She drew George Borrow’s House half way up the hill between Pottergate and Willow Lane.

Left: The C17 George Borrow’s House, Willow Lane by CM Nichols. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk. Right: the house today, viewed through a modern archway.

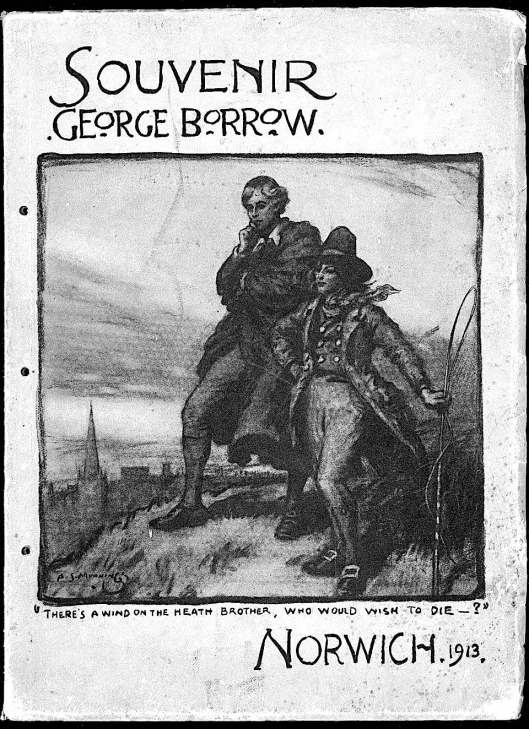

George Borrow (1803-1881) was a larger-than-life character: a boxer, a spinner of tales, a gipsy traveller and a linguist who taught himself Old Norse and Welsh. He was born in Dereham but his family lived for a while in Norwich where George was taught at Norwich Grammar School alongside Kate’s father and uncle [3]. In 1913 Kate was to provide engravings of the interior of the Borrow house for a souvenir booklet produced a decade late for Borrow’s centenary.

The George Borrow centenary souvenir booklet with cover by Alfred Munnings, who painted scenes of gypsy life. Courtesy of [11].

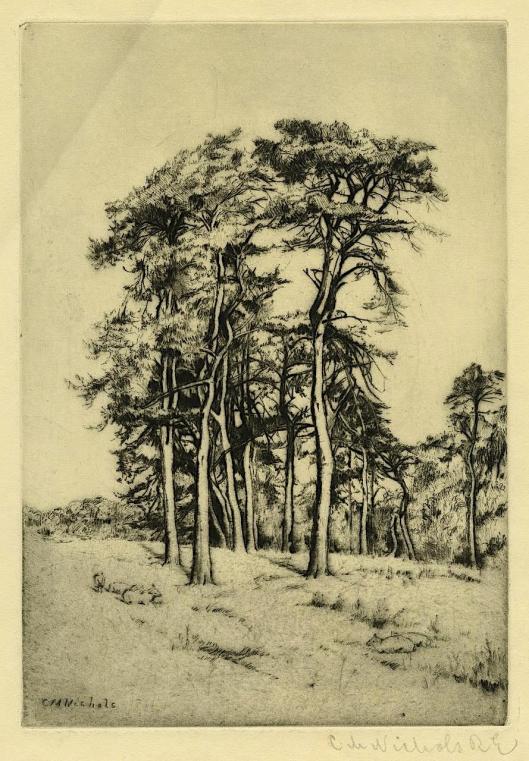

The Society (later the Royal Society) of Painter-Etchers was formed in 1880; two years later Kate submitted a diploma piece, Scotch Firs, for which she was elected the first female fellow.

Scotch Firs 1882. Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM : 1965.82.1

In 1882 Kate was baptised into the Catholic faith, causing a rift with her family. In 1891 she is recorded as living a few doors away at 12 Surrey Street and by 1900 she had ventured further along the road to Carlton Terrace.

![Surrey St 47 to 79 Carlton Terrace [6461] 1987-05-19.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/surrey-st-47-to-79-carlton-terrace-6461-1987-05-19.jpg?w=529)

Carlton Terrace at the south end of Surrey Street. George Plunkett’s photograph was taken in 1987, eight years after Edward Skipper and Associates restored the 1881 terrace for Broadland Housing Association. Kate Nichols lived at the far end. ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

Before St John’s Catholic Church (later Cathedral) was completed in 1910 Kate worshipped at the Old St John’s Chapel (1794), which is now the Maddermarket Theatre.

Left: Off St John’s Alley, The Old St John’s Catholic Chapel pre-1900 (from [12]). Right: Converted to the Tudor style Maddermarket Theatre in 1921.

For the frontispiece of a book celebrating Catholicism in Norwich Kate painted the new Catholic church from Chapelfield North [12].

Frontispiece of ‘A Great Gothic Fane’ by CM Nichols. From [12].

Kate age 66. From [12].

Kate Nichols’ closest friend was the wealthy Mary Radford Pym who lived in an exotic Tudor Revival house in Chapelfield (once home to my dental practice).

St Mary’s Croft (1881) in Chapelfield North

Mrs Pym was philanthropic. She funded the clocktower in Sheringham and gave land on Earlham Road to be used as a park. She also gave money to the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital for a nurses’ home; this funded Pym House on the corner of Unthank and Christchurch Roads [3].

Pym House, purchased in 1927. A plaque records that this was for the use of the Jenny Lind Children’s Hospital on the opposite side of Unthank Road, now the site of the Colman Hospital and prior to this the Priscilla Bacon Lodge.

In 1889, Mrs Radford Pym arranged for her good friend Kate to be installed as President of the newly-founded Woodpecker Art Club, a title she held until her death 34 years later. The Woodpeckers – who included Alfred Munnings among their members – were so named because they chipped away at wooden engraving blocks, unlike Kate who inscribed metal. In addition to outings the club held an annual meeting upstairs in ‘Princes’ high-class confectioners in Castle Street, owned by Margaret Pillow a friend of Mrs Pym.

From [1]

Kate died in 1923 and in her memory Mrs Pym arranged for a portrait, painted 20 years earlier by neighbour Edward Elliot, to be bought and donated to the Castle Museum. It was presented by Prince Frederick Duleep Singh, who succeeded Kate as President of The Woodpeckers (Frederick was son of the last Maharaja of the Sikh Empire, Maharaja Sir Duleep Singh, a favourite of Queen Victoria who lived in exile at Elveden Hall, near Thetford).

Miss Nichols by Edward Elliot. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM : 1923.75. This captures Kate around the late 1890s when overblown leg-of-mutton sleeves were fashionable.

In 1927 the Woodpeckers merged with the Norwich Art Circle (est. 1885), which continues as the Norfolk and Norwich Art Circle[13].

The colophon of Jarrolds of Norwich who printed Kate Nichols’ later drypoints

© 2019 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- Citizens of No Mean City (1910). Pub: Jarrold, Norwich.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/01/15/when-norwich-was-the-centre-of-the-world/

- Pamela Inder and Marion Aldis (2015). ‘A Forgotten Norwich Artist: Catherine Maude Nichols’. Pub: Poppyland Publishing, Cromer.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/07/15/the-end-of-the-unthank-mystery/

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1997). The Buildings of England: Norfolk I.Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/04/15/colonel-unthank-rides-again/

- http://www.hellenicaworld.com/UK/Literature/CharlesMackie/en/NorfolkAnnals2.html

- Letter by CC Lanchester to the Eastern Daily Press 20.9.1960.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/05/05/fancy-bricks/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/02/15/the-flamboyant-mr-skipper/

- https://www.gutenberg.org/files/21538/21538-h/21538-h.htm

- A Great Gothic Fane: The Catholic Church of St John the Baptist, Norwich (1913). Pub: WT Pike and Co., Brighton.

- https://www.nnartcircle.com/about.html

Thanks

I have relied for background on ‘A Forgotten Norwich Artist: Catherine Maude Nichols’ by Pamela Inder and Marion Aldis – a model of local historical research (and still available). I also thank Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk for permission to reproduce photographs (try the site: https://norfolk.spydus.co.uk/cgi-bin/spydus.exe/MSGTRN/PICNOR/HOME). Thanks, too, to Jonathan Plunkett for allowing access to his father’s invaluable collection of Norwich photographs: http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Website/.

One of my fave posts. Eric says George Borrow buried in Brompton cemetery Xx

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

Yes, just checked, Boy Eric is right. I must look deeper into Borrow’s life – a fascinating man.

LikeLike

Apparently she was co-founder of the Woodpeckers Sketch Club, with another fine artist, Miller Smith RBA born in Manchester, but resided in Norwich for a number of years, in different properties, I have been lucky enough to own two of his works of Cottages in The Street Costessey, they are now in the possession of the Owner of one of the Cottages.

LikeLike

Hello Peter, How wonderful to have two paintings of Old Costessey by Miller Smith. Do they show George Gunton’s cottages? My neighbour picked up several Kate Nichols’ engravings at local sales.

LikeLike

Thanks for this, and especially for the link back to Sir J.E. Smith!

LikeLike

You’re welcome Caroline. Smith is very much an unsung local hero. It’s a shame his garden is now under the bus station, just as Sir Thomas Browne’s is now lost in the city centre. BTW, tickled to see in your recent blog the connection between Snake’s Head Fritillary and fritillus = chessboard.

LikeLike

Wonderful – all completely new to me!

LikeLike

Thank you Heather. It was fascinating to learn a little of someone whose life overlapped with Norwich School artists.

LikeLike

Thank you – fascinating – but I was so disappointed to discover that Cottesey Hall has been demolished. It looked wonderful

LikeLike

It was the outstanding neo-Gothic building of its time. So sad it’s gone.

LikeLike

All new to me, too. Thank you for this wonderful post and all the photos showing what the places she drew look like now.

I will show this to my daughter who starts a three year degree course in Illustration at Norwich University of the Arts this autumn.

LikeLike

Hello Clare, Lucky daughter to be starting an Illustration degree at NUA.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reggie, enjoyed your last blog!

Greetings from Holland

LikeLike

Pingback: After the Norwich School | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Thanks for the info on her. I have a lovely work of what I now can assume to be the Norfolk countryside, and have been curious about the artist and the location for years.

LikeLike

I’d love to have a look at your engraving (I assume), Nancy. Do you think it’s possible to make out where it was drawn?

LikeLike

Pingback: Madness | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Female Suffrage in Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Hello, it may interest you to know that C.M. Nichols and a painter Miss C.M. Alston had a few Art exhibitions together. They were in group exhibitions together in 1900 and 1903, and then exhibited together, just the two of them in 1903 and 1906. Interestingly, Charlotte Alston was also a traveller and a Catholic, she had four brothers who were priests. I’ve been working on a blog post about Charlotte from time to time over a period of years, though it’s not as beautifully written as yours. Still, I do have some News snippets about their exhibitions which you may find interesting. 🙂 You can find the post here

https://blueseabluesky.blogspot.com/2023/07/charlotte-maria-alston-1868-1940.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sending your blog post to me; the parallels between the misses CM Alston and CM Nichols are fascinating and, as you say, their paths crossed at the Norwich Woodpecker sketch club.

You show three small thumbnails that CMA painted as ‘village street scenes’ but at least two of them are paintings of Norwich. The first is too small to identify with certainty but the second is clearly the ‘wonky’ timber-framed Augustine Steward House in Tombland, Norwich and the third is of Briton’s Arms in Elm Hill. Search engines have many images.

Good luck with completing your story (if that’s ever possible).

LikeLike