At one time Britain’s sea defences faced south, towards France and Spain, but when Napoleon occupied Holland our sights turned eastwards to possible invasion from the North Sea and Baltic. To counter this a naval base was established at Great Yarmouth in 1796 and rapid communication with the Admiralty in London required something more than flags and burning barrels of tar [1].

Courtesy Gareth Fudge. Creative Commons

In the C17 a scientific hero of mine, Robert Hooke, suggested that the recently invented telescope could be used to read secret messages. I can’t show you a portrait of Doctor Hooke for he fell out with Sir Isaac Newton – President of the recently-formed Royal Society – about his contribution to the Theory of Gravity and a vengeful Newton is claimed to have ensured that no image of Hooke remained [but read 2].

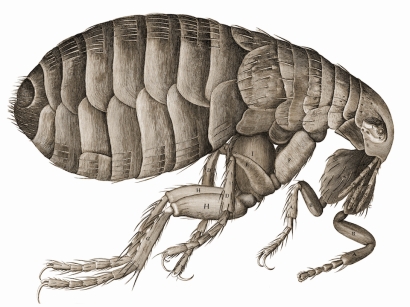

Hooke was one of the first to use a compound microscope – a microscope based on two or more lenses. He is known to cell biologists for coining the term cell for the ‘holes’ he saw in sections of plant material – these reminded him of monks’ cells in a monastery.

Perhaps the first drawing of plant ‘cells’ (actually the holes left in cork by dead cells). Robert Hooke, ‘Micrographia’ 1665.

Hooke is probably more generally known for having drawn a flea using his microscope, underlining the point that these experiments in optics took place in the year of the Great Plague.

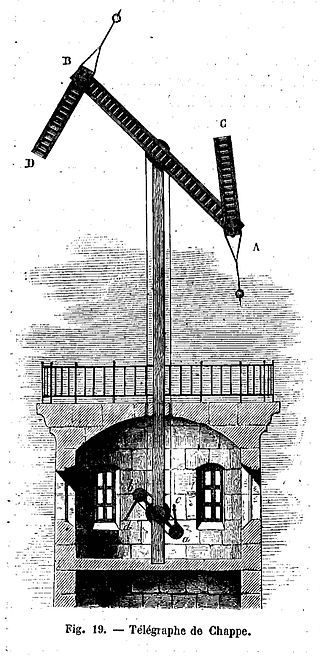

The first successful practical use of the telescope to convey messages over long distances was developed by the Frenchman Claude Chappe, who coined the term ‘semaphore’ (Greek: sēma = sign; phoros = carrying) [3,4]. At the beginning of the C19 the French could communicate rapidly between Paris, Lille and Brussels using Chappe’s telegraph that eventually covered the whole of France and extended to Amsterdam and Venice [3]. Each station consisted of a tower from which protruded a mast holding movable arms; the next station, some 10-20 miles away, read the code by telescope and relayed the message down the line [5].

Chappe’s telegraph. Courtesy Wikipedia

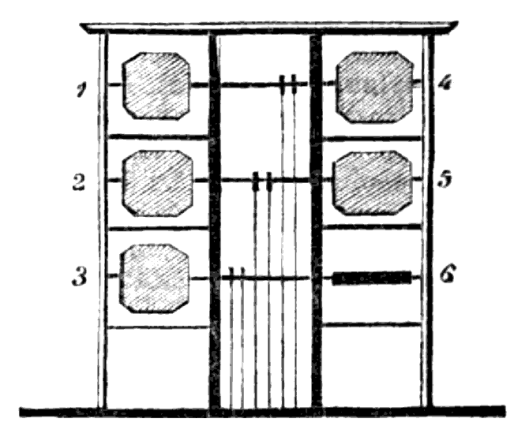

In 1795 Lord George Murray, who was Bishop of St David’s in Wales, offered a different model to the British Admiralty, for which he was rewarded £2000 [6]. This consisted of a six-metre-high shutter frame with three pairs of panels, each about a metre square. Each swivelling panel could be pulled by ropes and flipped between edge-on or face-on, producing sixty four combinations. Unlike the Chappe system, in which each setting corresponded to a coded message, Murray combinations corresponded to single letters and could spell out words (although some combinations denoted predetermined sentences) [3].

The Murray shutter telegraph. Shutter 6 is in the horizontal position. Courtesy Wikipedia.

A shutter station. Courtesy of [6]

Stations might consist of a living room, a room for operations, a small garden and coal shed [7]. Four to six naval men ran the station in twos or threes with one manning the shutters while the other(s) looked through high-power telescopes [8].

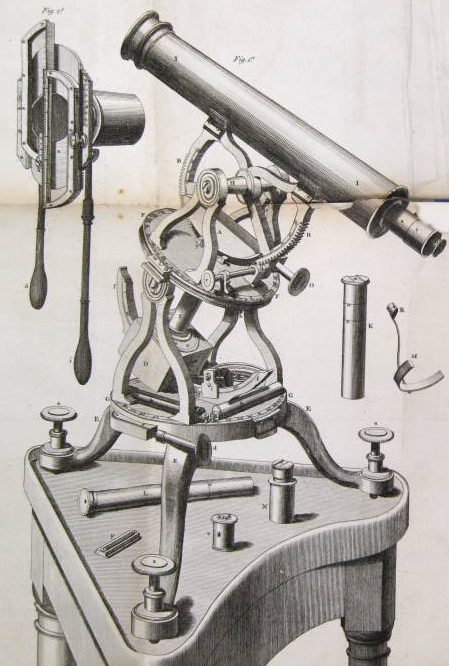

Dollond’s achromatic telescope, late C18. Courtesy @sciencemuseum

Because the component colours of ‘white’ light (think rainbow) have different wavelengths it is difficult to focus them to the same point through a lens, resulting in blurred images with a colour fringe. But John Dollond (1706-1761) – son of a Huguenot silk weaver in Spitalfields, London – patented a compound lens that improved the telescope [9]. He cemented a concave lens of flint glass to a convex lens of crown glass, which largely overcame chromatic aberration. The Admiralty shutter telegraph used Dollond* telescopes, possibly their top-of-the-range ‘Twelve Guinea’ instrument.

*[Dollond’s optical business became Dollond and Aitchison in 1927 and merged with Boots Opticians in 2009].

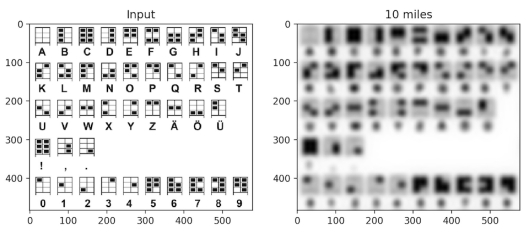

Evidently, the system worked but I still found it surprising that naval telescopes of 1800 could discern shutter patterns from 10 miles away. Alex Pietrow of Stockholm University simulated what a Dollond telescope should be able to see. His calculated degradation shows that an experienced operator could still make out the code.

Simulation of the degradation of shutter patterns over 10 miles. Courtesy Alex Pietrow, Stockholm University

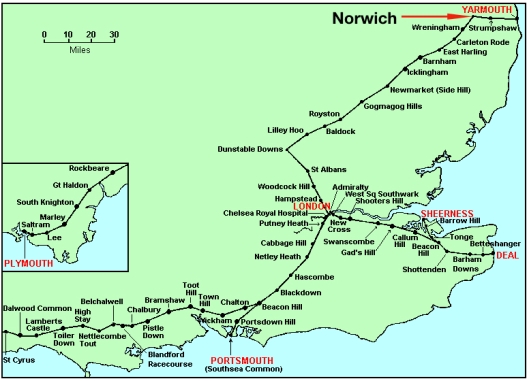

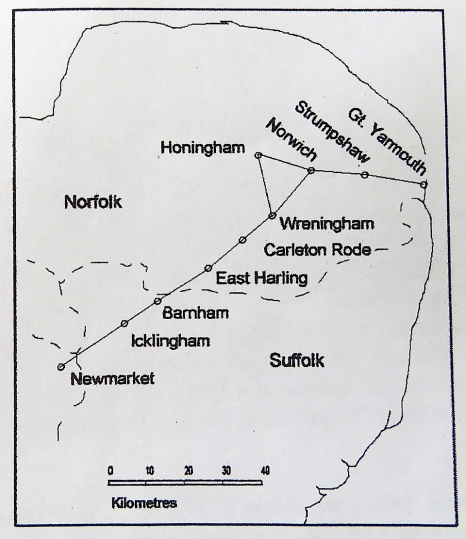

The first experimental station, built in 1795 above Portsmouth, was the start of the line to Deal consisting of 15 relay stations; it took another 10 years to extend to Plymouth. Relay stations were 7-10 miles apart but the 1808 line to Great Yarmouth involved intervals up to 11.7 miles [1] and required three right-angle bends, including one at Norwich.

Anticipating problems of mist and fog over low-lying ground the contractor, George Roebuck, avoided a line through Essex. Instead, he turned north-west out of London to the Chilterns, before heading north-east into East Anglia [3].

The first station inside Norfolk was in East Harling. But before searching for the site I visited the church and its many treasures of the Late Middle Ages. The east window contains the best rural collection of C15 stained glass from John Wighton’s Norwich workshop, which also made the stained glass for St Peter Mancroft, Norwich. By 1460 the workshop was run by John Mundeford, from a family of Dutch emigrés, whose father William had also led the Wighton workshop [10].

Painted glass ca 1440-80 by the Wighton workshop from SS Peter and Paul East Harling

Hidden away in the tracery of the east window is a fuzzy squirrel whose siblings can be seen on the shield of a Lovell family tomb-chest.

The animal provides a clue to the identity of the woman who sat for Holbein’s enigmatic ‘Portrait of a Lady with a Starling and a Squirrel’.

By Hans Holbein the Younger ca 1526-28. Courtesy of National Gallery London.

David King the historian of stained glass, who comes from a family of Norwich glass restorers, recognised the squirrel as an emblem of the Lovell family. He also suggested that the starling was a pun on East Harling, which could be spelled Estharlyng in the C16. The sitter could therefore be Anne, wife of Sir Francis Lovell (d. 1551), who – as Esquire to the Body of Henry VIII – was well-placed to have commissioned Holbein on his first visit to England [11].

The former site of the shutter telegraph station (1808-14) was up a gentle East Anglian slope about a mile out of town. The first edition OS map shows that a Telegraph House stood nearby [3].

Telegraph Hill East Harling (TM0085)

Next, on to Carleton Rode and the shutter station whose location is commemorated in the name, Telegraph Farm. The farm is situated two miles north-west of the village but the station itself is given as Telegraph Pit to the SE of the farm itself [12].

Driving across this unrelievedly flat land forces one to think how shutters on top of a hut could ever be seen ten miles away. To address this, Bernard Ambrose plotted the cross-sections between stations using the contours on OS maps [3]. The fact that a line of sight was possible only if modern-day shrubs and hedges were removed gives a sense of how difficult it is to see across these flatlands (and explains the preoccupation of East Anglian painters with big skies).

The next station was at Wreningham, ‘on high ground near the church’ [8] – again, straining the definition of ‘high’.

Wreningham All Saints

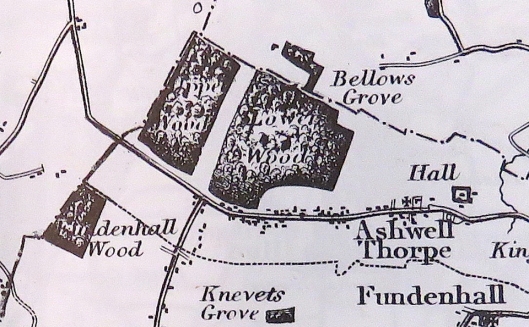

Ambrose [3] calculated that a shutter station near Wreningham All Saints would have to have been raised about 16 metres. Instead, he proposed that a lost church – St Mary’s, formerly marked on OS maps – was the actual site of the station. Even so, another problem was the inconvenient presence at Ashwellthorpe of a large ancient wood, blocking the line of sight between Carleton Rode and Wreningham.

Ashwellthorpe Wood from Faden’s map of 1797. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council

But Bryant’s map shows that by 1826 a drive had been cut through Ashwellthorpe Wood. Bernard R Ambrose suggests this was done to provide a line of sight for the shutter telegraph [3].

From Bryant’s map 1826 showing the now-bisected Ashwellthorpe Wood. Note Knevet’s Grove – Knevet or Knyvet crops up later.

Ashwellthorpe Wood, mentioned in the Domesday Book, has endured since the Anglo-Saxon period but in 2012 the silent invasion of ash dieback disease from the continent initiated sudden changes. The wood contains 40% ash trees so even if some are resistant the balance of native broadleaved trees will be transformed, as it was some decades ago by Dutch elm disease. I recall the rookery in the giant elms louring over my daughter’s kindergarten. Once, when I drove in late, spraying gravel over the carpark, the commotion catapulted birds out of their nests. “Look,” my daughter said, “pepper in the sky.” The elm are gone and now the ash of Ashwellthorpe are heading that way.

Dr Anne Edwards of the John Innes Centre, and a volunteer at Ashwellthorpe Woods, used molecular techniques to establish the presence there of ash dieback disease, the first in the UK. Photo: ©edp.co.uk

From Wreningham, the telegraph line continues north-east to Norwich. In 1803 a commercial telegraph station had been erected on top of Norwich Castle for signalling to Yarmouth but this earlier project was abandoned because smoke from the city affected visibility [8].

‘Norwich Castle 1793-1809’. The artist is ‘unattributed’ but the watercolour is based on an engraving by Robert Ladbrooke for ‘Bell’s Antiquities of Norfolk’. Could the structure on the battlements be part of a previous semaphore system? ©Norfolk Museums Collections

In Norwich Castle Museum there is an echo of Ashwellthorpe in the form of a triptych by the Master of the Magdalen Legend (ca 1483-ca 1530). Also known as the Seven Sorrows of Mary, the Ashwellthorpe Triptych was commissioned by Christopher Knyvet of Ashwellthorpe when Henry VIII sent him to The Netherlands. Christopher is seen in the left-hand donor panel while his wife Catherine kneels on the right [13], both accompanied by their name saint: St Christopher – patron saint of travellers – carries a child on his shoulder, and St Catherine holds the spiked wheel on which she was martyred.

The Ashwellthorpe Triptych NWHCM 1983: 46 ©Norfolk Museums Service. Ashwellthorpe Church contains a photographic replica.

The actual site of the Admiralty telegraph in Norwich was near the present-day water tower at the top of Telegraph Lane in Thorpe St Andrews, ca 2 km east of the city centre and 15 km north-east of Wreningham.

In the vicinity of the water tower the 1886 OS map shows two features with the name ‘telegraph’: Telegraph Cottages and Telegraph Plantation.

The high ground in Thorpe Hamlet, 2km east of Norwich city centre. 1886 OS map courtesy of the National Library of Scotland under a Creative Commons licence.

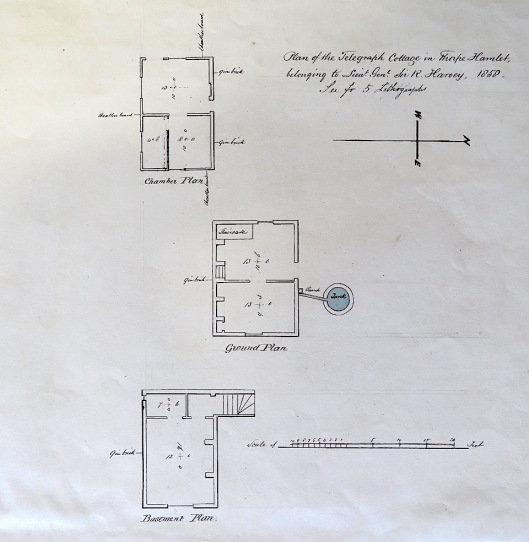

In the Norfolk Record Office I found a plan of Telegraph Cottage, Thorpe, owned in 1858 by the Harvey family of Crown Point. This may well have been the shutter station and, if so, gives a rare indication of the layout. The building of brick and weatherboard is comprised of three storeys (basement, ground floor and chamber) and is only 20 feet wide and 13 feet deep. Windows are placed along the east-west axis.

Plan of Telegraph Cottage, Thorpe Hamlet, Norwich. Courtesy Norfolk Record Office MC91/2/14

This ridge of high ground to the immediate north-east of Norwich would have been ideal for visual signalling. At around 220 feet this ridge is – in East Anglian terms – high enough; think of steep Gas Hill nearby and Kett’s Heights from which Robert Kett’s rebels fired down upon the city in 1549.

The site of the Norwich shutter station on Telegraph Lane, Thorpe, is marked with a black star. A conjectural station near Honingham to the west is marked with a blue star. ©openstreetmap

In his survey of the Norfolk telegraph line Ambrose [3] suggested that the Thorpe station might have been hampered by smoke from the city or by mists over low-lying ground to the south. He therefore proposed that a reserve shutter station be sited on Telegraph Hill (blue star above) near Honingham, to the west.

Bernard R Ambrose proposed a reserve station to the west of Norwich, at Honingham. From [3].

Telegraph Hill, ca 2 miles north of Honingham village.

Ambrose’s hypothesis has the virtue of explaining Telegraph Hill but signals from that station would still have to penetrate the atmospheric pollution over Norwich city in order to be read by the Norwich station at Thorpe. So perhaps mists over the low-lying riverland south of Norwich were really the problem. But whichever way they arrived at Norwich, signals from the south had to be redirected eastwards to Yarmouth and to achieve this the shutters were either larger than usual (so that they could be seen at an angle) or the station had two shutter frames facing different directions [1, 3].

The last shutter station before Yarmouth was at Strumpshaw where there is a tump – a proper hill just south of the church. This hill, previously the site of sand and gravel extraction, is now a recycling centre. Driving down the west side of this wooded slope I found a waypost pointing westward to a distant Norwich.

Even without a tripod, my bridge camera could make out landmarks on the Norwich skyline; for example, St Peter Mancroft.

St Peter Mancroft, Norwich (arrowed) from Strumpshaw Hill. The Thorpe shutter station would have been somewhere on the right

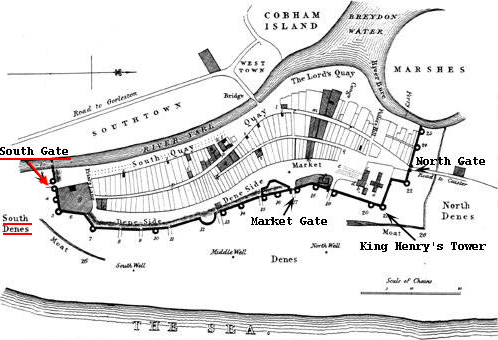

In 1798, King George III sent a message to both Houses of Parliament stating that preparations were being made by the French for the invasion of this kingdom [14]. That was seven years before the Battle of Trafalgar and 17 years before Waterloo and it is hard for us now to appreciate the widespread fear of a Napoleonic invasion, especially on the east coast. In response, the Yarmouth Corporation voted £500 towards the town’s preparations and granted the Admiralty a piece of ground on the South Denes “for the convenience of naval officers and men to attend the signals” [14].

Yarmouth’s South Gate, arrowed. Map courtesy of Sue Walker White

Great Yarmouth has one of the best-preserved medieval town-walls, dating back to 1261 when Henry II granted the right to enclose the town. Eleven defensive towers remain, including the South-East Tower.

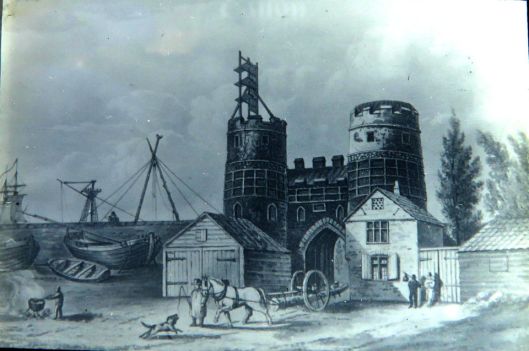

However, the South Gate – where the shutter station was based – has not survived. Palmer’s History records, “A small wooden hut was erected, which after the war was occupied by the inspecting commander of the coast guard”; this hut would appear to be illustrated below [14]. A private residence, Telegraph House, was later built on the enlarged site and demolished in the 1950s.

Lantern slide of the South Gate, Great Yarmouth, with shutter telegraph, ca 1816. Courtesy of Norfolk Record Office 530/1/43

In 1814 the shutter stations were sold after Napoleon was defeated and banished to Elba. When Napoleon escaped, the Portsmouth and Deal shutter lines were replaced with a semaphore system but not the Yarmouth – London branch, marking the diminished threat to Norfolk shores after the defeat of the French Navy at Trafalgar.

In 1817-19, the 44-metre high Nelson Monument was raised not far from the Yarmouth shutter station. Nelson’s column in Trafalgar Square is topped by the man himself while at Yarmouth we have Britannia looking inland, supposedly towards Nelson’s birthplace at Burnham Thorpe, North Norfolk [15].

©2019 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- J.B. Fone (1996). Signalling from Norwich to the Coast in the Napoleonic Period. Norfolk Archaeology vol XLII Pt III. pp 356-361.

- https://blogs.royalsociety.org/history-of-science/2010/12/03/hooke-newton-missing-portrait/

- Bernard R. Ambrose (2001). The Shutter Telegraph. The Journal of the Norfolk Industrial Archaeology Society pp 17-29.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Chappe

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semaphore_telegraph

- http://www.douglas-self.com/MUSEUM/COMMS/telegraf/telegraf.htm

- http://www.icknieldwaypath.co.uk/WEB%202%20-%20The%20London%20to%20Yarmouth%20Telegraph%20System%20.pdf

- H.V. James (1977). The London-Yarmouth Telegraph Line 1806-1814. Norfolk Archaeology vol XXXVII pp 126-129.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dollond

- D. J. King. (2006) The Stained Glass of St Peter Mancroft, Norwich, CVMA (GB), V, Oxford.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portrait_of_a_Lady_with_a_Squirrel_and_a_Starling

- http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?MNF14978-Site-of-post-medieval-telegraph-station&Index=14037&RecordCount=57338&SessionID=b29b5abb-334d-48d6-b9ac-06d7f37666ad

- https://vads.ac.uk/large.php?uid=85353&sos=0

- C.J. Palmer (1854). Edited and updated version of Manship’s History of Great Yarmouth. vol 2. Pub: L.A. Meall, Gt Yarmouth.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Britannia_Monument

Thanks

I am grateful to Alex Pietrow of Stockholm University, Neil Handley at The College of Optometrists, and Sam H and Bart Fried of the Antique Telescope Society Forum. I thank Dr Anne Edwards and Professor Allan Downie of the John Innes Centre, Norwich, for discussions on ash dieback. I am grateful to staff of the Norfolk Record Office for their cheerful assistance. And thanks to Theo for navigating.

VISIT LOWER WOOD, ASHWELLTHORPE, MANAGED BY THE NORFOLK WILDLIFE TRUST. https://www.norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk/wildlife-in-norfolk/nature-reserves/reserves/lower-wood,-ashwellthorpe

Well I’ll be darned…lovely stuff.

LikeLike

Thank you

LikeLike

Truly fascinating research. Thank you.

LikeLike

I’m so pleased you liked it, Anne

LikeLike

Never knew about this, fascinating. Thanks

LikeLike

I had stumbled across a few Telegraph Hills or Lanes and now this makes sense. Thank you for following.

LikeLike

Fascinating stuff

Sent from Yahoo Mail on Android

LikeLike

I appreciate the comment, Sally

LikeLike

Very interesting and as well researched as ever, Reggie – thank you.

LikeLike

Does the telegraph route go past you, Clare?

LikeLike

I don’t think so. We are too far East.

LikeLike

Thank you for this. I was trying to establish why my 5xgreat grandfather Thomas Topper (a Telegraphist/Naval Officer) was in Norwich at the time of his youngest son’s baptism in 1811 – at St Martin-at-Palace. It seems likely he had been transferred from London (he also worked at West Square, site of another shutter and then semaphore tower). Really interesting article.

LikeLike

Only too pleased to help. My wife is currently researching her 4xgreat grandfather and his naval connections (but no naval telegraph so far).

LikeLike