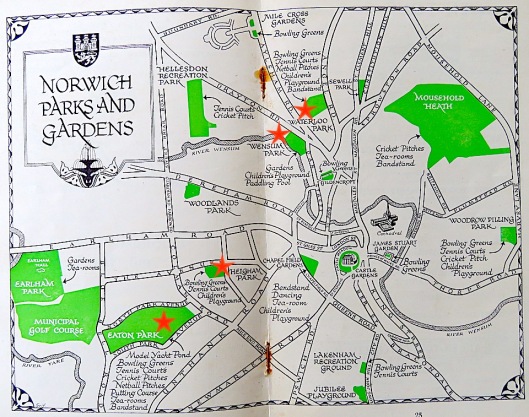

In the 17th and 18th centuries, visitors to Norwich were surprised at the amount of open ground within the walls of a thriving city [1]. But by the early twentieth century the city had burst its confines and green space was needed in the suburbs to counter-balance the Victorian terraces and the vast council estates that followed. This month I focus on the man who created the city’s C20 parks, generating work for the many who were still unemployed after World War I.

From “Norwich Parks: Summer Handbook” ca 1947. Starred: Eaton, Heigham, Wensum and Waterloo Parks.

From the C16 onwards, when accommodation had to be found for the influx of weavers from the Low Countries, the large houses of the rich textile merchants were subdivided into cheap tenements and their courtyards filled with shoddy speculative buildings. These ‘yards’ housed the Norwich poor and were the object of slum clearances from the late C19 to well into the C20 [2]. It was to this ‘land fit for heroes’ that soldiers returned from WWI and many found themselves out of work:

“In 1921, there was no doubt action was needed in Norwich. The City had 7000 unemployed people with another 1040 on short time, 1500 married men and 1200 single men were registered for relief work.” AP Anderson [3].

In 1919, just after he was demobbed from the Army, Captain Arnold Edward Sandys-Winsch (1888 – 1964) applied for the job as Parks Superintendent in Norwich [3].

Courtesy of [3]

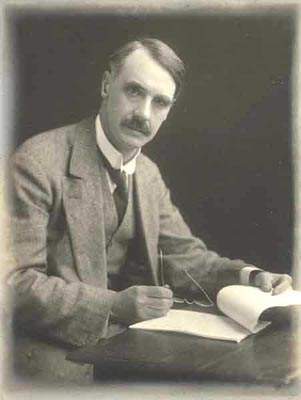

Before the war Sandys-Winsch had trained with landscape architect and garden designer, Thomas Hayton Mawson, whose interest in town planning and public parks is likely to have played a part in gaining Sandys-Winsch the position.

Thomas Mawson ©Chris Mawson

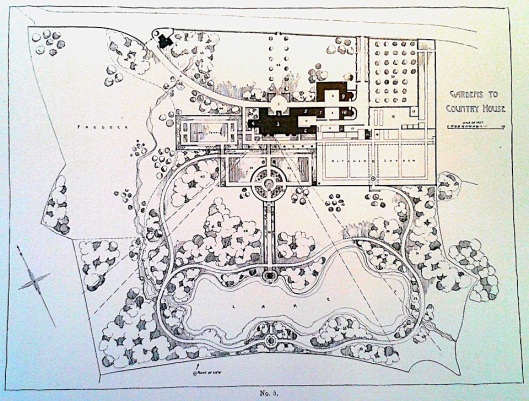

In 1900 Mawson had published The Art and Craft of Garden Making, linking his name to the Arts & Crafts approach to gardening pioneered by the partnership between gardener Gertrude Jekyll and architect Edwin Lutyens [4]. Sandys-Winsch’s designs for Norwich would emerge out of these formative influences.

Plan by TH Mawson, from ‘The Art and Craft of Garden Making’ (1900), courtesy of [5].

When The Captain was appointed, Norwich only had Chapelfield Gardens, Gildencroft, Sewell Park (funded by relatives of Anna Sewell, author Black Beauty) and the largely unreconstructed pleasures of Mousehold Heath (given to the citizens of Norwich by The Church in 1880 [6]). It was quickly suggested to Sandys-Winsch that he could put the unemployed to work by making new parks [7, 8].

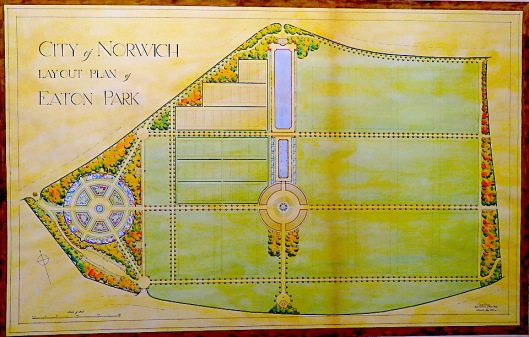

In 1906, using funds provided by the Norwich Playing Fields and Open Spaces Society [7, 8], the council bought 80 acres from the Church Commissioners comprised of four large grazing fields between Eaton Hall and Earlham Hall. This rough area to the south-west of the city was at one time the site of the Royal Norfolk Agricultural Show; during WWI it served as a practice ground for trench warfare but between 1924 and 1928 Sandys-Winsch employed 103 men to transform it into Eaton Park [7,8,9].

Capt Sandys-Winsch’s 1928 plan for Eaton Park [Oddly, the compass arrow points south, not true north]. The 400 yard scale bar, lower left, makes the park over a mile long. Norfolk Record Office ©Norfolk County Council

The ‘third field’ (red star) near Bluebell Road was left as rough grass to accommodate circuses until after WWII. Now it contains the pitch-and-putt golf course [7,8].

Eaton Park 1928. The ‘third field’, now the golf course, is starred.

Other recreational features included tennis courts, cricket squares, bowling greens and a model yacht pond. Eaton Park was The Captain’s prestige project and considerable effort went into the structural elements: mainly the radial plan of the large formal gardens and a centrepiece provided by quadrant pavilions surrounding a domed bandstand.

A colonnade being made from reconstituted stone. ©Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

The park was opened in 1928 by Edward, Prince of Wales with Captain Sandys-Winsch in close attendance.

The tall figure of The Captain stands behind Prince Edward with stick in hand, 1928. Photo George Swain ©Norfolk County Council. Courtesy of Archant.

A 29 second movie of this visit survives. PRESS HERE

Courtesy of British Pathé

At a time when few people had cars, finances were tight and ‘holiday at home’ was the watchword, the parks enjoyed a popularity that is difficult to appreciate today. Correspondence between the Parks and Gardens Committee and the Norwich Electric Tramways Company mentions cheap fares to Eaton Park during band performances on Sundays, 2-6pm [10].

![Eaton Park band playing in bandstand [B290] 1932-05-16.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/eaton-park-band-playing-in-bandstand-b290-1932-05-16.jpg?w=529)

A military band concert in Eaton Park, 1932. ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

Eaton Park bandstand today

The buildings in Eaton Park show a restrained Italianate classicism although there is said to be an Indian Mogul influence [8]. The closest approximation to an Indian structure would be the domed bandstand, which can be traced through Mawson’s designs to the dome-shaped ‘chattri’ pavilions [11] used in Indian architecture and repeatedly employed by Lutyens in his designs for New Delhi.

From the New Delhi office of Sir Edwin Lutyens 1912, based on a model of a ‘chattri’ roof. Courtesy RIBApix

One of the quadrant pavilions now houses the excellent Eaton Park café whose sandwiches give a humorous nod to the park’s creator.

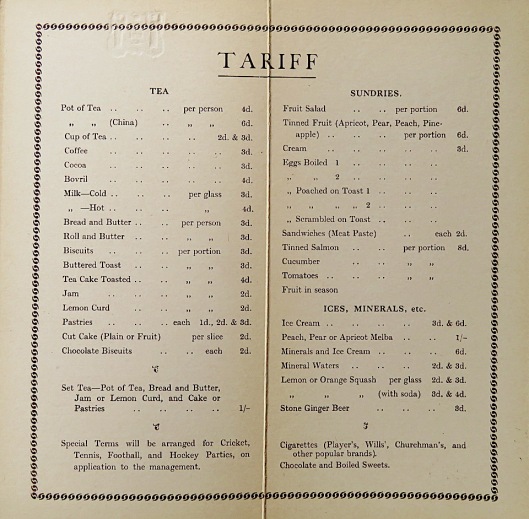

By comparison, the menu from Sandys-Winsch’s time as Parks Superintendent seems joyless. Probably printed in the tail of post-war austerity (WWII), the no-frills tariff offered a ‘set tea’ of bread and butter with jam, a pastry and a pot of tea, enjoyed in clouds of Churchman cigarette smoke.

Eaton Park Café ‘tariff’ from, I guess, the 1950s.

A dozen or so years earlier the pavilions had been used for a less happy purpose. In 1940, Britain was at war and the Council was preparing trenches in parks and gardens across the city to afford some shelter against air attack.

Surface shelter in Norwich parks against bombing. Norfolk Record Office N/EN 1/73

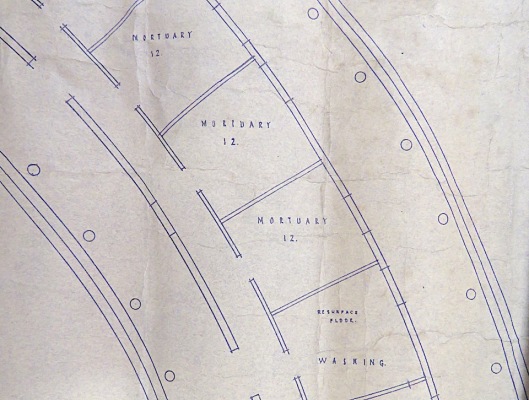

For Eaton Park the Air Raid Precautions Committee had drawn up plans to convert the pavilions to air raid mortuaries.

Plan by City Architect LG Hannaford (3.2.1940) to adapt Eaton Park Pavilion to air raid mortuaries. Norfolk Record Office N/C 1/195

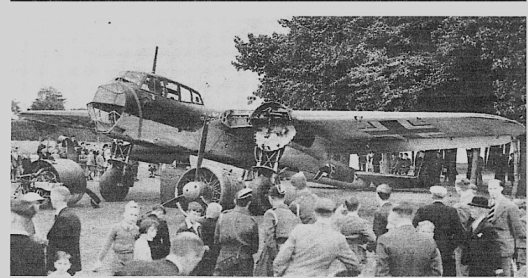

North of the city, Waterloo Park was used as a temporary mortuary after two German bombers – a Dornier 17 and a Junkers 88 – dropped bombs during the first air raid in 1940 [12]. There was no warning siren; 27 were killed, including 10 at Boulton & Paul’s Riverside Works and five women on Carrow Hill who had just clocked off at Colman’s Carrow Works. By a curious twist a Dornier DO17, which had been shot down over Duxford, was displayed at Eaton Park in 1940.

The Dornier ‘Flying Pencil’ displayed in Eaton Park, 1940. Courtesy of Friends of Eaton Park [3], reprinted from the Eastern Evening News ‘Letters’ Dec 5 1985.

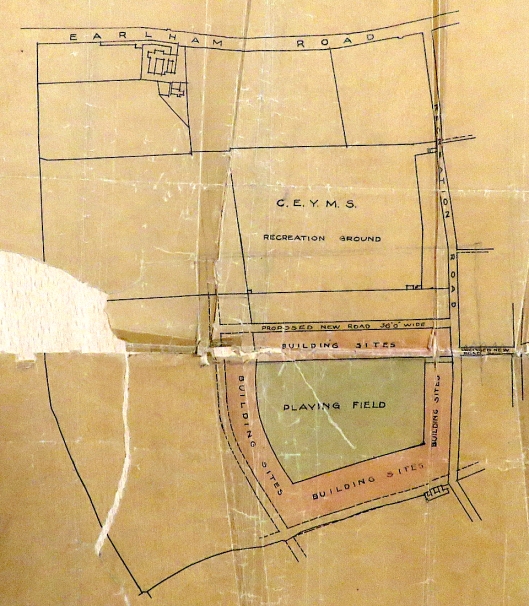

Less than a mile north-east of Eaton Park lies Heigham Park. Its survival amongst the blizzard of terraced house-building can again be attributed to the foresight of The Norwich Playing Fields and Open Spaces Society [7, 8, 13]. In what became the Golden Triangle, they had bought a large plot of land so that children at Crooks Place School (now Bignold) and the nearby Avenue Road School could take part in sports and recreation. In 1909 the mayor inaugurated Heigham Playing Fields by kicking off a soccer match between these schools [7]. But by 1920, with encroaching suburbanisation, architect George Skipper was proposing to build four terraces around half of the field while the other half remained a recreation ground for the Church of England Young Men’s Society football team – the forerunner of The Canaries.

The fourth (upper) side of the proposed building site (red) around Heigham Park was never built, leaving The Avenues to bisect the larger field and to pass without too much of a dogleg down Avenue Road. Courtesy NRO N/EN 24/138

The CEYMS premises at Brigg Street, Norwich

Heigham Park, opened in 1924, was the smallest of Sandys-Winsch’s parks and the first ‘modern’ park opened in the city [7, 8]. Heigham Park had room for tennis courts, bowling green, floral beds and a general play area but lacked the large built structures that characterise Eaton Park.

Heigham Park today

What it does possess is a timber pergola on stone pillars, one of Mawson’s signature features.

The tennis courts at Heigham Park were once distinguished by wrought iron gates with railings in the form of sunflowers designed in the 1870s by Wymondham’s Thomas Jeckyll (no relation to Gertrude). The subject of an earlier post [14], the sunflower became emblematic of the Aesthetic Movement that celebrated the impact of Japanese design upon Western art. Now, reproductions of these sunflowers form the gates at Eaton Park and Chapelfield Gardens (and provide the header for my local history site on Twitter).

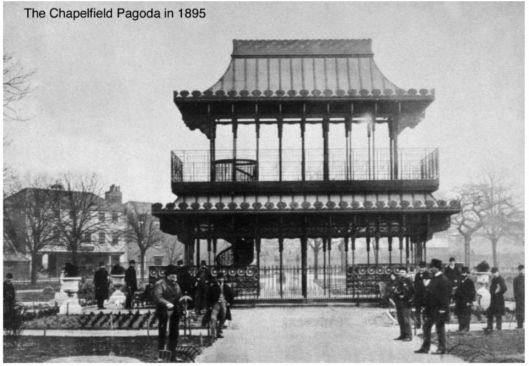

The original Heigham Park sunflowers were some of the 73 sunflowers, three feet six inches tall, that formed the railings around the oriental pagoda in Chapelfield Gardens. The pagoda was an exhibition piece, of international acclaim, that Jeckyll designed for Barnard Bishop and Barnards’ Norfolk Iron Works in Coslany but it was dismantled after WWII [14].

The Chapelfield Pagoda. The sunflower railings can just be seen surrounding the base of the pagoda. Courtesy http://www.racns.co.uk.

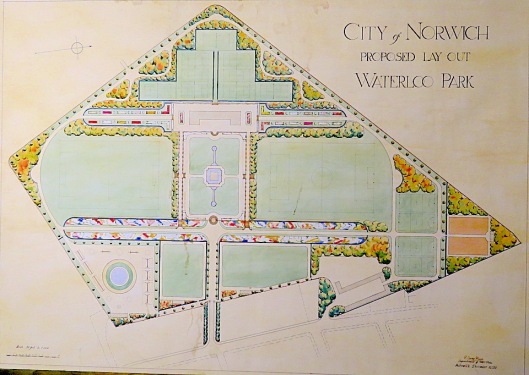

In 1897 the Norwich Playing Fields and Open Spaces Association leased, from the Great Hospital Trust, land that would become Waterloo Park in the north of the city [7,8]. Originally named Catton Recreation Ground, Waterloo Park was redesigned by Sandys-Winsch and opened in 1933 [15]. This, his second largest project, was structurally more complex than Heigham Park.

Courtesy of Norfolk Record Office ©Norfolk County Council

As at Eaton, this park provided for active recreation with grass tennis courts, football pitches, bowling greens and a children’s playground. In addition, there were formal gardens (with the longest flower border in the city), pergola walks, a bandstand, a pavilion and those colonnades.

In 2000, AP Anderson suggested that the ‘small central feature’ at top centre of the pavilion was not intended for a clock but a sculpture of the heads of three city’s worthies [8]. During the Heritage Lottery Fund-sponsored renovations of 1998-2001, a sculpture was commissioned of the three wise monkeys.

‘See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.’ Artist: Alex Johanssen 2000

In 2017, after the pavilion had been closed for 15 years, it reopened as Park Britannia, a café run by serving and ex-offenders who have turned this into a popular and vibrant place to visit. Try it.

The Britannia Café’s ice-cream van ‘Meghan’

Wensum Park emerged out of an abandoned project to build a swimming pool and paddling pool on the banks of the River Wensum [7,8]. After work ceased in 1910 the site became a refuse dump but in 1921, with a 40% government grant, the council set the workless to turn it into a garden park, which opened in 1925. Perhaps because of its gentle slope to the river, which made it unsuitable for playing fields, Sandys-Winsch decided to make this one of his less formal gardens. Unlike Heigham Park it did contain a building: a balustraded viewing terrace with a pavilion/shelter beneath.

George Plunkett’s photograph of 1931 shows that the pool and fountain have been lost, as has the paddling pool by the riverside.

![Wensum Park fountain and shelter [B155] 1931-00-00.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/wensum-park-fountain-and-shelter-b155-1931-00-00.jpg?w=529)

The circular pool with fountain jets, seen here in 1931. ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

The last of the Sandys-Winsch Five is Mile Cross Gardens. In the 1920s Professor Adshead of Liverpool University set out a ‘modern housing estate of quality’ [7] and from the outset the gardens were an integral part. Sandys-Winsch implemented the planned twin gardens, each one-acre. While Eaton, Heigham, Waterloo and Wensum parks are Grade II* listed, Mile Cross Gardens are Grade II and, unlike the others, did not receive Heritage Lottery funding in 2000. This secondary status is reflected in the dereliction of the two small pavilions and the loss of S-W’s stone and timber pergolas (although vestigial bases remain).

Minor works: The much more substantial pavilion at Sloughbottom Park was also designed by Sandys-Winsch.

Probably the greatest contribution to the general wellbeing of Norwich’s citizens are the 20,000 trees that Sandys-Winsch planted around the city’s roads. Minutes of the Parks and Gardens Committee [10] show that this was part of an unemployment scheme; one small project employed 15 men for 20 weeks [10]. In doing this the Council took advantage of Ministry of Transport grants to plant trees on Class I and II roads. Another scheme drawn up by Sandys-Winsch involved Newmarket, Aylsham and Dereham Roads (all Class I) and Earlham Road (II) at a cost of £900, £408 of which was grant-aided. The trees immeasurably improve the quality of life in this city.

Newmarket Road

©2019 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/09/15/norwich-city-of-trees/

- Frances and Michael Holmes (2015). The Old Courts and Yards of Norwich. Pub: Norwich Heritage Projects.

- http://friendsofeatonpark.co.uk/captain-sandys-winsch/. (Do visit this great website).

- https://www.greatbritishgardens.co.uk/garden-designers/35-thomas-mawson-1861-1933.html

- https://merl.reading.ac.uk/news-and-views/2014/05/discovering-the-landscape-5-mawsons-the-art-craft-of-garden-making-1900/

- https://www.edp24.co.uk/norfolk-life-2-1786/norfolk-history/46-mousehold-heath-1-214282

- Geoffrey Goreham (1961). The Parks and Open Spaces of Norwich. Self-published, Norwich. Available for reference at Norwich Millennium Library.

- A.P. Anderson (2000). The Captain and the Norwich Parks. Pub: The Norwich Society.

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1001282

- Minutes of the Parks and Gardens Committee 1921-1928. NRO N/T 22/2

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chhatri

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Website/raids.htm

- Clive Lloyd (2017). Colonel Unthank and the Golden Triangle. See colonelunthanksnorwich.com

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/01/06/jeckyll-and-the-sunflower-motif/

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1001348

Thanks. For providing photographs I am grateful to: Helen Mitchell, Friends of Eaton Park; Jonathan Plunkett of the georgeplunkett.co.uk website; Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk; Rosemary Dixon, Archant Photo Library. Thanks, too, to Sarah Scott.

What a start to the day – a feast of the places which are a daily delight, and so much to follow up! Thanks even more than usual!

LikeLike

A prize for the fastest read! You are fortunate in living so near two of these wonderful parks. Reggie

LikeLike

What a great man, a delight, why don’t they make them like that today!

Katonah / NY

LikeLike

Hey Maart, S-W did so much for this city but we shouldn’t forget a humane city council who created so many projects for the large number without work. Reggie

LikeLike

This man is a hero. The City needs another to help us face biodiversity losses caused by climate change.

LikeLike

It hadn’t dawned on me that it’s 100 years on since Sandys-Winsch started his grand project. Who in the C21st can continue what he started?

LikeLike

Always fascinating thanks for giving us this insight into our wonderful parks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another reason to be cheerful in Norwich. Reggie

LikeLike

Thanks Reggie – fascinating glimpses of a proud heritage, thorough and original! Theo

LikeLike

Thank you Theo

LikeLike

I always felt Waterloo Park under rated during my time in norwich. Could have been full of life much more. Maybe it’s changed in the last decade. I also wished they had put in a bigger park when they overhauled the riverside development. Great post-as expected, as always 😉

LikeLike

Thanks Daniel. I can report that Waterloo Park is looking good. The new café injects some life, brings visitors. Sadly the bowling green is locked and running wild.

LikeLike

Another splendid introduction to some of our wonderful open spaces. Wensum Park seems to be overlooked these days – it’s a long time since i visited it but I remember being told as a child that alongside the river was a ‘swimming pool’ which was damaged by bombs during the war. Anderson’s Meadow which isn’t a formal park, just a green space was the Norwich City Council rubbish tip in the 1940’s

Keep up the good work .

Don Watson

LikeLike

Hello Don,

Wensum Park did seem a little beyond its glory days. In looking thorough Goreham’s book I did see photos of bathing along the river bank but no structures remain (see Geoffrey Goreham (1961). The Parks and Open Spaces of Norwich. Available for reference at Norwich Millennium Library).

All best wishes, Reggie

LikeLike

What a treat … I have always wanted to know more about the parks. A HUGE thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you Jane

LikeLike