Norwich grew rich from the export of worsted, the fine woollen fabric that took its name from the nearby village of Worstead, but between 1535 and 1561 there was a rapid decline, probably due to the success of lighter foreign fabrics known as the New Draperies [1]. To revive the city’s textile trade, the mayor persuaded the Fourth Duke of Norfolk in 1566 to ask permission from Queen Elizabeth I to invite ‘thirty Douchemen of the Low Countreys of Flaunders’ each with up to 10 members of family or servants [2]. Some had already come to London and Sandwich and the group of 24 ‘Dutchmen’ and six French-speaking Walloons that arrived in Norwich represented a new wave of immigrants – Strangers – whose name lives on around the city.

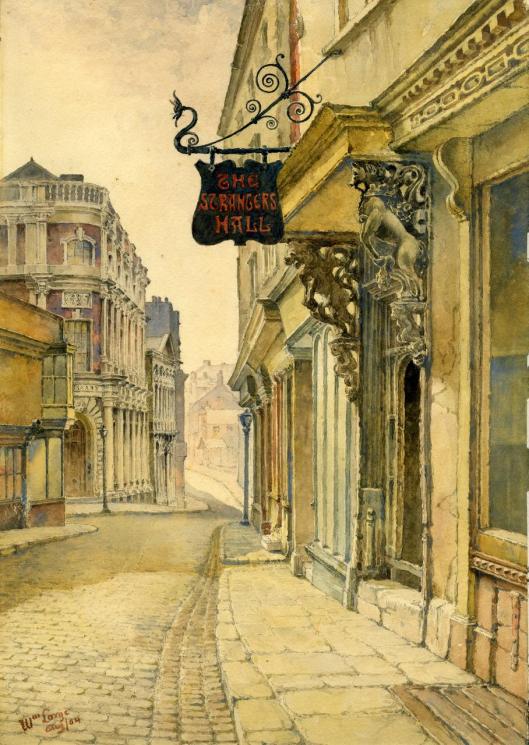

Strangers’ Hall, now a museum. By William Large 1904. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collections 1937.118.2

The mayor, Thomas Sotherton, played a key part in inviting the master weavers to Norwich in expectation that they could introduce New Draperies that were becoming difficult to import from the Low Countries. However, the council refused to sanction what they saw as competition and so the mayor was forced to admit the foreign weavers under his own seal. There is evidence that at least one family of Strangers rented accommodation in his house, which later became known as Strangers’ Hall [1].

A room used by the Sotherton family in Strangers’ Hall

‘Stranger’ is derived from the Old French for foreigner – étranger. Although the word is now synonymous in Norwich with the immigrants from the Low Countries (and, a century later, the French Huguenots), ‘stranger’ had previously applied to anyone who came from outside the city.

Sotherton was buried in the church just behind his house, St John Maddermarket. We have previously encountered the Maddermarket in connection with the dye, madder, used for dyeing textiles Norwich Red [3]. This is part of the Charing Cross district previously known as Shearing Cross [4] where woven cloth would be sheared to remove surface fibres and level the nap.

Monument to Thomas Sotherton 1608 in St John Maddermarket by James Sillett (1764-1840). Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM: 1951: 235.1234.1324.

This was not the first wave of immigrants: the historian Blomefield stated that Flemings came to nearby Worstead in the C12; then in the C14 Phillippa, Queen of Edward III, encouraged her ‘good and trew weevers‘, the Flamands (French Flemish), to come to Norwich and Norfolk [5]. By 1400, trade between Norwich and the Low Countries was deeply entrenched, 137 ‘aliens’ were recorded as living in the city c1440, in 1426 John Asger from Bruges was Norwich Mayor [6] … and Brice the Dutchman left his mark in the form of the Green Man roof boss in the cloisters of Norwich Cathedral [1].

In 1467 ‘Brice the Dutchman’ was paid four shillings and eight pence to carve this foliate head in Norwich Cathedral cloisters [1]

But in 1567, the year following the arrival of the 30 families, there was a far greater influx, this time of religious refugees. Philip II of Spain was determined to eradicate Calvinism from that part of the Holy Roman Empire over which he ruled – the Spanish Netherlands.

John Calvin, the French theologian, proposed a variety of Protestantism in which some were predestined for salvation by God while the rest were condemned to eternal damnation.

The Spanish Netherlands comprised ‘most of the states of modern Belgium and Luxembourg, as well as parts of northern France, southern Netherlands, and western Germany with the capital being Brussels’ [7]. To enforce the Inquisition the brutal Duke of Alba led 10,000 Spanish soldiers, killing hundreds of Protestants and forcing thousands to flee.

The Spanish Netherlands (grey) in 1700. Courtesy Wikipedia

Possibly mindful of religious zealotry, Queen Elizabeth I commanded the Bishop of Norwich in 1568 ‘to make a detailed return of the whole body of strangers.’ The census showed that 1,480 of the arrivals were Dutch speakers (the Dutch language being a lower form of the German language, Deutsch) and 339 French-speaking Walloons [1]. However, the majority of the ‘Dutch’ came from Flanders while some of the Walloons also came from Flanders as well as what is now northern France [1, 2]. Boundaries have changed but we are talking about an area oscillating around modern Belgium. Indeed, an oration to Queen Elizabeth I on the reverse of Braun and Hogenberg’s map of Norwich (1681) refers to ‘Belgic friends’.

By 1571 the Norwich Strangers numbered just short of 4,000 [2]. There was no corresponding census of native English but it is thought that the immigrants comprised about a third of the population. A letter home urged a family member to bring ‘two little dishes to make up half a pound of butter … for here it is all pig fat’ [2]. Another reported, ‘You would never guess how friendly the people are together’ … but these were early days.

The influence of the Low Countries can be seen here in the crow-stepped and Dutch gables of Norwich Cathedral Close and around the east coast

The mayor succeeding Sotherton, Thomas Whalle (1567-8), was not supportive of the Strangers ‘for they did but sucke the lyvinge away from the English’, but he failed to expel them [1]. A more disturbing event occurred in 1570 when John Throgmorton, gentleman of Norwich, conspired ‘to expulse the strangers from the city and the realm.’ Upon ‘the sound of a trumpet and beat of drum’, men recruited at Harleston midsummer fair and at ‘Bongey and Beccles’ would march upon Norwich and fund their enterprise by stealing the mayor’s plate. Only 21 years after Kett’s Rebellion it is jarring to read that a member of Kett’s family, Thomas Ket, should have betrayed his co-conspirators, resulting in Throgmorton and two others being hanged, drawn and quartered [8,1].

The two languages continued to separate the Dutch speakers and the French speakers. The Dutch worshipped in St Andrew’s and Blackfriars Halls, which had been bought for the city by Augustine Steward after the Reformation. For a while they also worshipped at St Peter Hungate [1], which had been the Pastons’ church when they lived in Elm Hill.

The Dutch church at Blackfriars’ Hall, from Samuel King’s plan 1766.

The French were permitted to worship in the chapel of Bishop Parkhurst, who had gone into exile under Queen Mary’s reign and would have been especially sensitive to religious intolerance. In 1637, however, these Walloons moved to St Mary-the-Less in Queen Street, Norwich.

The ‘hidden’ church of St Mary-the-Less, its entrance (far right) currently blocked by scaffolding

Elizabeth’s census of 1568 shows that although the Dutch population was predominantly associated with weaving it contained a self-sufficient community of potters, bakers, school teachers, doctors, gardeners etc [8,1]. They also had their own pastors and perhaps the most well-known was Johannes Elison. When he and his wife returned to Amsterdam their wealthy son commissioned Rembrandt to paint their portraits – two of only three full-length portraits that he painted.

Johannes Elison and his wife Maria Bockenolle/Bonkenell 1634 by Rembrandt. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts Boston

The two communities were also divided by the kind of material they wove; these stuffs had ‘more hard names than any Apothecary hath upon his Boxes or Gallypots’ [9]. The Dutch were only allowed to make baytrie, ‘wet greasy goods’ that had been wetted, cleaned and thickened: the Walloons produced ‘dry woven goods’ known as caungeantry woven from yarn composed of long, combed, parallel fibres [1,8]. These fibres of worsted could then be woven with lighter yarns like flax or silk. While the new ‘Norwich Stuffs’ produced by the Walloons grew in popularity demand declined for the thicker, plain ‘bays’ produced by the Dutch.

The name ‘baize’ for the cloth used to cover snooker tables derives from the worsted-weave ‘bays’, Old French = baies. This gives a sense of the type of material. It could be dyed a variety of colours including dun-coloured ‘bay’. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

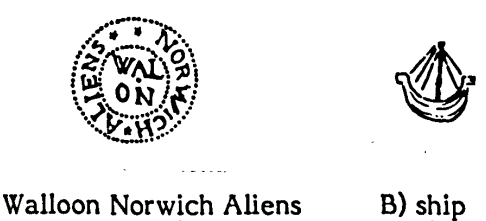

There was strict control over standards. In 1571 a ‘Book of Orders for the Straungers of the Cittie of Norwiche’ laid down 24 articles for the manufacture of textiles; in addition, ‘Sealers’ or ‘Searchers’ were appointed to inspect every piece of fabric in Sealing Halls [5]. Whoever contributed to less than perfect material (dyer, weaver, finisher) was fined and very poor goods were torn in two. Satisfactory goods produced by Norwich citizens received a lead seal with the city arms (castle and lion); Norfolk fabric was sealed with the castle but on faulty material the name was placed in a ring. Strangers had neither castle nor lion and their faulty material was sealed with ‘aleyne’ or alien in a ring.

Drawings of Walloon lead seals, from [10]. The ship was sometimes used for ‘alien’ work.

A C17 Norwich lead cloth-seal. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Service

The city carefully regulated the Strangers’ lives and trade: for example, they could not stay out after the striking of St Peter Mancroft’s eight o’clock bell and they could lodge no other Stranger for more than a night without obtaining the mayor’s permission. In response the Strangers sent a letter to the Queen’s Privy Council numbering the advantages they brought, including: manufacture of textiles not previously made in the city; increased employment; the money they paid the council (and they paid double the national tax or ‘subsidy’); they were law-abiding and God-fearing and looked after their own poor. The Privy Council informed the council that the Strangers had royal endorsement: ‘the Quenes Majestie … (praise) you to continue your favoure unto them’ [8].

In 1578, Queen Elizabeth I came to see her new subjects for herself. Upon entering St Stephen’s Gate she was greeted with a pageant performed by the ‘artizans strangers‘. This took place on a long platform on which young girls spun worsted yarn surrounded by loyal mottoes and paintings representing aspects of textile manufacture [2]. The Dutch minister presented the Queen with a ‘very curiously and artificially wrought silver-gilt cup’, worth £50 and in return the Queen gave £30 for the poor Strangers.

Elizabeth I is said to have watched a pageant from a rear first-floor window of Augustine Steward’s house in Elm Hill. Just visible to the left is Blackfriars’ Hall that Steward, one-time Mayor and Sheriff of Norwich, bought for the city [11]. Steward’s House is now the Strangers Club, founded in the C20 to entertain guests from out-of-town.

Despite the friction the Norwich textile trade continued to flourish, the Strangers married into local families and their otherness gradually faded. ‘Outlandish’ names on the original list of 30 incomers, such as Jerusalem Pottelbergh and Ipolitè Barbè, either died out or were anglicised.

Left: A ‘Jan/John Dutchman’ headstone late C18 from St Mary’s Hickling; right: was ”Ditchman’ a local variant? St Stephen’s Norwich

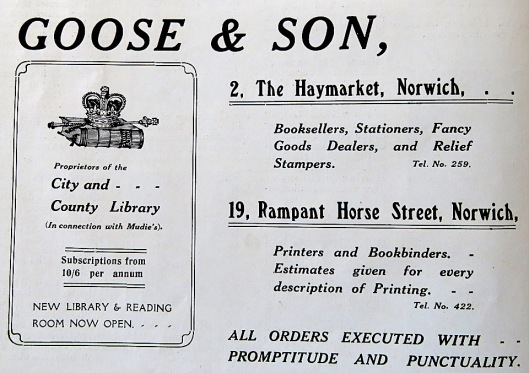

Dutch names mutated towards the English; James Minns the Victorian carver, whose name crops up in previous posts [12], was a descendant of Mins; the Muskett family into which Clement William Unthank married were originally Mosquaert; and Goez and Rumpf became Goose & Rump printers.

Goose and Rump later became Goose & Son when Agas Goose went into partnership with son Arthur. Advertisement ca 1910.

The Huguenots: When Phillip of Spain was harrying Protestants in the Spanish Netherlands, including French-speaking Walloons, the French monarchy was persecuting its own Protestants. Following the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (1572) in which 5,000-30,000 Parisians were killed the Edict of Nantes granted religious toleration but this was withdrawn in 1685 and many fled the country. Some settled in England and some came to Norwich, including the well-known Martineau family [see 13]. These refugee French Protestants – the Huguenots – are associated with the development of ‘Norwich crape’, a mixture of worsted and silk, but though they have weaving in common with the incomers of the 1500s these later arrivals represent a different historical strand.

St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, by François Dubois. The Huguenot leader, Admiral Coligny, is seen hanging out of a window. Wikipedia

Bonus track: Norwich is known for its interest in things botanical. This may derive from the Dutch who imported Florists Feasts (floral competitions) that became an annual event by the time of Charles I [14]. In discussing the Norwich Dutch the historian Thomas Fuller wrote, “the Rose of Roses [Rosa mundi] had its first being in this City” [15]. Certainly, this ancient striped rose was associated with Norwich as illustrated by this seventeenth century cushion.

Turkey-work cushion showing the Norwich City coat-of-arms surrounded by striped Rosa mundi roses. Twelve of these cushions were presented in 1651 by the mayor to be used by aldermen when Blackfriars’ Hall was used as a council chamber [see ref 14]. Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM: 1904.60.1

©2019 Reggie Unthank

Sources.

- Frank Meeres (2018). The Welcome Stranger. Pub: Lasse Press, Norwich.

- R.W. Ketton-Cremer (1957). The Coming of the Strangers. Chapter in, Norfolk Assembly. Pub: Faber & Faber.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/07/15/the-bridges-of-norwich-1-the-blood-red-river/

- Helen Hoyte (2017). The Strangers of Norwich. Pub: Red Herring Publishers.

- Walter Rudd (1923). The Norfolk and Norwich Silk Industry. In, Norfolk Archaeology XXI, p245.

- Penelope Dunn (2004). ‘Trade‘. Chapter in, Medieval Norwich. Eds Carol Rawcliffe and Richard Wilson. Pub: Hambledon and London.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_Netherlands

- Francis Blomefield, (1806). ‘The city of Norwich. Chapter 27 Of the city in Queen Elizabeth’s time’. In, An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 3, the History of the City and County of Norwich, Part I (London, 1806), pp. 277-360. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-hist-norfolk/vol3/pp277-360.

- John Taylor (1650). A Late Weary, Merry Voyage and Journey pp17-18. London.

- Geoffrey Egan (1987). Provenanced Leaden Cloth Seals. PhD thesis University College London. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1349956/4/488665%20full.pdf

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/elm.htm

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/05/05/fancy-bricks/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/03/15/three-norwich-women/

- Ruth E Duthie (1982). English Florists’ Societies and Feasts in the Seventeenth and First Half of the Eighteenth Centuries. Garden History vol 19, pp 17-35.

- Thomas Fuller (1840). The History of the Worthies of England vol II. Pub: Thomas Tegg, London.

Thanks: I appreciate the kind assistance of Bethan Holdridge, Assistant Curator, Norfolk Museums Service.

This post is dedicated to my Dutch friends Maarten and Eva Kleiweg de Zwaan.

Thank you, Reggie, for great blog and dedication: Maarten and I are touched! See you in The Netherlands.

LikeLike

Fascinating – thank you

LikeLike

Thank you for the kind feedback Anne.

LikeLike

A great read….fills in a lot of information that I didn’t know, though I have researched weaving in Norwich from the 1750s – assuming you don’t mind a plug for it: https://paulharley.wordpress.com/2019/05/22/norwich-weaving-1750-1900/

LikeLike

Paul, Your post is a tour de force on the finer aspects of the Norwich weaving trade and I am delighted to plug it.

LikeLike

I love all the fascinating nuggets of information here, Reggie. The history of the words baize and bay and also the Rosa Mundi rose of which I have two bushes in my garden.

LikeLike

Norwich has always been strong on horticulture and in botanical research. I wonder how many other species originated here?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am forwarding this article to our Dutch friends to encourage them further to come over to visit us here in Norwich. Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi Cathy, The Dutch should feel very much at home here.

LikeLike

Hi Colonel, fascinating insights. I particularly like the references-so rare to see nowadays. Thank you

LikeLike

Hi Al, I hope the citations are not too intrusive – they’re the habit of a lifetime. Reggie

LikeLike

Pingback: The Norwich School of Painters | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Street Names #2 | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: James Minns, carver | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Thomas Browne’s World | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The Plains of Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Parson Woodforde goes to market | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The Sons of Flora | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH