Few women in the late eighteenth/early nineteenth century were able to achieve national celebrity, but Amelia Opie did [1]. As a young Norwich woman she became a well-known author, publishing several novels and works of poetry. Her luminous friends included Lady Caroline Lamb, Mary Wollstonecraft (A Vindication of the Rights of Woman), Sir Joshua Reynolds, JMW Turner, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Sir Walter Scott, Maria Edgeworth, Elizabeth Fry; and in later life, when she became a Quaker, her name headed the list of 187,000 women petitioning for the abolition of slavery [2].

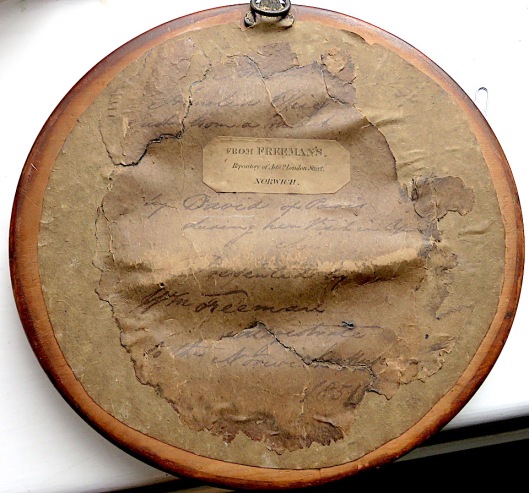

On a recent visit to Norwich School I was shown a medallion of Amelia Opie in her high Quaker bonnet. I wrote briefly about her in Three Norwich Women [1] but I’m revisiting because the medallion – or at least the back of the medallion – opens a small window on Norwich in Amelia’s time. I call her Amelia because that’s what her biographer, Ann Farrant [2], called her but, still, I hesitate since she was a stickler about forms of address:

‘… do not call me Mrs Amelia Opie. I am not Mrs Amelia Opie but Mrs Opie or among friends Amelia Opie … Mrs Opie, Norwich is my lawful and proper designation’ [2].

Mrs Opie’s medallion. Courtesy of Norwich School

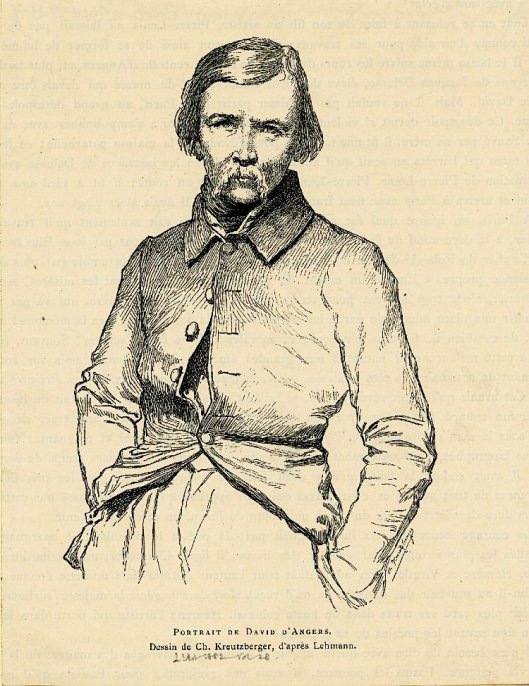

The name ‘David’ is inscribed beneath the sitter’s shoulder. Napoleon was known by the single name but the only artist with sufficient celebrity to be known by a single name was Jacques-Louis David, the foremost painter in revolutionary France. The ‘Opie’ David, however, refers to the sculptor Pierre-Jean David, from the town of Angers, who made medallions of more than 500 well-known figures. When Pierre-Jean entered the studio of Jacques-Louis David he differentiated himself from his patron by adopting the name of David D’Angers.

After Britain and France declared peace in 1802 Amelia travelled to France. As the granddaughter of a Dissenting minister, daughter of a doctor with radical sympathies, and travelling with companions who supported the French Revolution, there seems little doubt that Amelia intended to see France’s new society for herself. In the group was her husband, John Opie RA, one of whose attractions as a suitor was that he’d agreed to live in the Opie household if Amelia proved averse to leaving her beloved father [2].

John Opie self-portrait 1789. His wife was to outlive him by 46 years

Amelia had been taught French by her great friend, the Reverend John Bruckner from Leiden in The Netherlands, who was pastor to the city’s French-speaking Protestants at St Mary-the-Less in Queen Street (and, later, to the Dutch Strangers in Blackfriars’ Hall). She is said to have insisted that John Opie paint a portrait of Bruckner as a condition of their marriage.

Amelia had an ‘almost obsessive interest in Napoleon’ and once, when she contrived to see him passing by, ‘saw him very near us, and in full face again.’ But two years later Amelia became an unbeliever when Napoleon snatched the crown from the Pope, placed it on his own head and declared himself Emperor; as she said, ‘the bubble burst’ [2].

Napoleon Crossing the Alps, by Jacques-Louis David (1801)

It had been thought that Amelia met David D’Angers on this visit but her biographer, Ann Farrant, makes it clear that it wasn’t until 1829, when Amelia was a widow and a Quaker with a high Quaker bonnet, that she first met David D’Angers in person [2].

Portrait of David d’Angers ©British Museum. 1006,U.2424

When Amelia revisited France she formed a strong friendship with David D’Angers. She was pleased her portrait on the medallion was ‘like’; she also noted that he’d managed to make the Quaker bonnet look a little like the classical Phrygian cap that the French revolutionaries wore as their bonnets rouges [2].

Left: the Phrygian cap worn by Attis, second century AD. Right: a French revolutionary with bonnet rouge, by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson. The Phrygian cap is said to have been worn by liberated slaves in Greece and Rome.

The back of the frame is equally interesting.

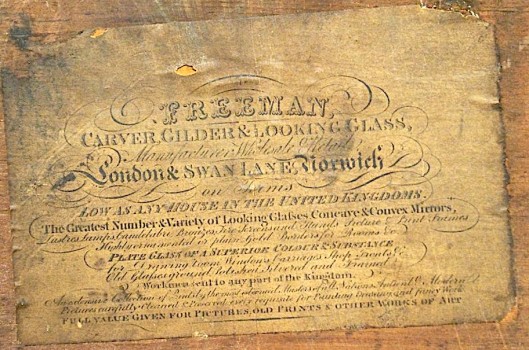

Freeman’s of London Street was founded by Jeremiah Freeman but the Freeman in the time of the Opie medallion would have been his son William (1783-1877). He is listed as proprietor of a ‘General Furnishing Warehouse and Repository of Arts’ at Number Two London Street.

William Freeman, Mayor Norwich 1843-4, Sheriff 1842. By Frederick Sandys, dated 1848. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM: 1949.102

Describing Freeman as a proprietor of a general furnishing warehouse seriously underplayed his business for he employed 63 men, women and apprentices producing furniture and gilt frames of the highest quality. As a frame-maker he would have been in competition with Norwich School artist James Thirtle who also made picture frames, notably for his brother-in-law, John Sell Cotman [3].

Early C19 Rococo Revival composition mirror by William Freeman of Norwich ca 1825. Courtesy Farrelly Antiques, Oxon

The label on the mirror gives Freeman’s address as ‘London and Swan Lane’. The wording implies the existence of a London branch but may simply mean his London Lane shop not the capital. Swan Lane is off present-day London Street. Courtesy Farrelly Antiques, Oxon

Freeman made furniture for Norfolk’s grand country houses, including Felbrigg Hall and Blickling Hall.

Gilt and gesso console table with an Italian marble top, by Freemans of Norwich 1825-1850. ©BlicklingHall@National Trust/Sue James

Three generations of Freemans were embedded in the artistic life of the city. Jeremiah (1763-1823) was President of the Norwich Society of Artists in 1818 – a post held by William himself two years later. William’s son, William Philip Barnes Freeman (1813-1897), went to Norwich School with John Crome’s son and was taught drawing by John Sell Cotman. In 1854 the first meeting of the Norwich Photographic Society was held on their premises [4].

The River at Thorpe Reach by William Philip Barnes Freeman (1813-1897), a late member of the Norwich School of Painters. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM: 1969. 301.3

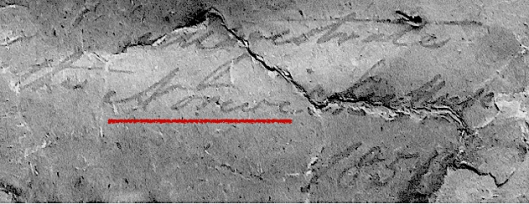

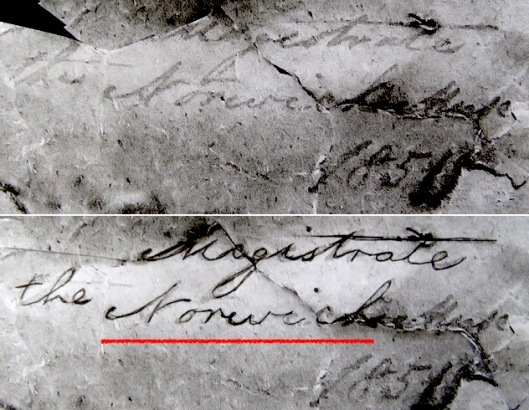

In addition to Freeman’s label on the reverse of the medallion, a faded inscription has been preserved: “Amelia Opie cast from a macet (i.e., maquette or preliminary model) by David of Paris during her visit in April (and here the original paper is torn). Presented by Wm Freeman Magistrate to the N …” but this and the following tangle of letters are difficult to decipher. The final line has just the date,“1851”, two years before Amelia’s death.

My first impression was that the difficult-to-decipher word beginning with ‘N’ was ‘Noverre’. This turns out to be incorrect but, as my old maths master insisted, I’ll show my workings, if only for the glimpse they give into contemporary Norwich society.

The Noverres were a Swiss-French Protestant family who lived in The Chantry adjacent to the Assembly House. Augustin had been ballet master at Drury Lane Theatre London, with David Garrick while brother Jean-George, back in France, had been dancing master to Marie-Antionette. One evening, just as he left the stage, Augustin was caught up in an anti-French fight. He mistakenly thought he had run an assailant through with a sword and fled to Norwich where he is said to have been sheltered by French Huguenot silk weavers [5].

Augustin Noverre (1779-1854) by Norwich School artist, Joseph Clover. Norwich Assembly House

Augustin’s son Francis (1773-1840) – who had been born in Britain – came to Norwich to teach dance, deportment and aspects of cultural refinement required in polite society. He built the west wing of the Assembly House for his ballroom. Long before she became a Quaker, the adolescent Amelia was an enthusiastic dancer; a friend recalls dancing ‘from seven to eleven’ at a reception for Prince William Frederick held at Amelia’s father’s house [2]. Amelia certainly knew of the Noverres since her husband John painted a portrait of the two Noverre children.

Augustin and Harriet, children of Francis and Harriet Noverre. Painted by John Opie ca 1805.

Public assemblies in the Assembly Rooms weren’t all stately minuets and cotillions for at the end of the evening the ladies would retire to remove the hoops from their skirts in readiness for country dancing. ‘At Assize Week in Norwich, the double doors between ballroom, card-room, and tea-room were opened up, and country dances danced along the length of the three rooms’ [6].

Country Dance, by William Hogarth. From, The Analysis of Beauty Plate 2. Wikimedia Commons

At some stage, the original inscription on the reverse of the medallion was glued to a new backing without closing the horizontal tear that runs along the penultimate line. On a print, I cut out the tear and joined the original edges. What I’d unconfidently construed as ‘Noverre’ can now be seen to be part of ‘Norwich’; however, the short final word (4-5 letters, florid italic capital) defeats my crossword-solving app and leaves Mr Freeman’s intention opaque.

After excising the gap (above) the two halves of ‘Norwi-ch’ could be rejoined (below).

The Norwich School medallion resembles the bronze plaque by David D’Angers in the National Portrait Gallery. The profile reappears on the marble bust by David D’Angers that forms the centrepiece of a display of anti-slavery artefacts in Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery. Amelia’s support for the abolitionist cause originated with her mother who, after her parents had died, became very attached to her black nurse [2].

Left: The Opie medallion ©National Portrait Gallery, London. Right: Marble bust of Amelia Opie by Jean-Pierre David D’Angers, Paris 1836. When the bust was delivered to Amelia from Paris she didn’t dare open it for three weeks in case it was frightful [2]. Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery.

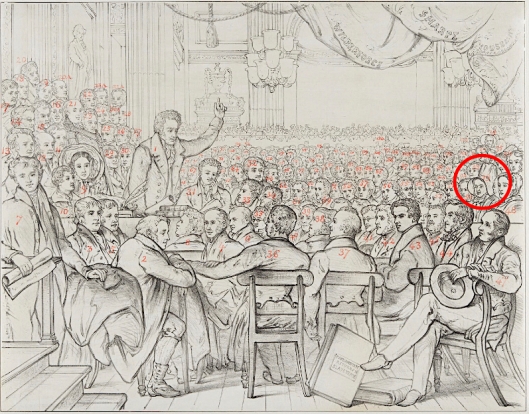

In 1825, in her mid-fifties with both husband and father dead, Amelia joined the Society of Friends. Now, she worshipped in the Friends’ Meeting House in Upper Goat Lane instead of her father’s chapel, the Octagon in Colegate [1]. Her high Quaker bonnet made Amelia a distinctive figure amongst those who attended the 1840 Anti-Slavery Society Convention.

A key to ‘The Anti-Slavery Society Convention 1840’ by JA Vintner, based on the painting by BR Haydon. ©National Portrait Gallery

There is a description of a lost photograph of Amelia: ‘in her Quaker dress, in old age, dim, and changed, and sunken, from which it is very difficult to realise all the brightness, and life, and animation which must have belonged to the earlier part of her life…’ [7]. Some of this youthful spark was captured by John Opie just after he and Amelia were married.

Amelia Opie 1798, painted by John Opie RA. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, London. Creative Commons Licence.

This was the painting on which Mrs Dawson Turner based her etching of Amelia in 1822. Mary Turner was the wife of Dawson Turner FRS (1775-1855) – banker, botanist, art collector – who had employed JS Cotman as drawing master to his family in Yarmouth. This etching of Amelia, which prettifies the Opie portrait, was made towards the end of Cotman’s time at Yarmouth by which time Mrs Dawson Turner would have been familiar with his etching techniques [3].

Mrs Opie, 1822. Etching by Mrs Dawson Turner from John Opie’s painting (above). Courtesy of Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery.

Long before she renounced fashion and adopted plain Quaker garb the 21-year-old Amelia had published an anonymous work on the Dangers of Coquetry. It therefore comes as a surprise to learn that she asked the Norwich School painter Joseph Clover to ask Mrs Turner to modify the likeness. To achieve this to Amelia’s satisfaction Mary Turner went through five iterations [2].

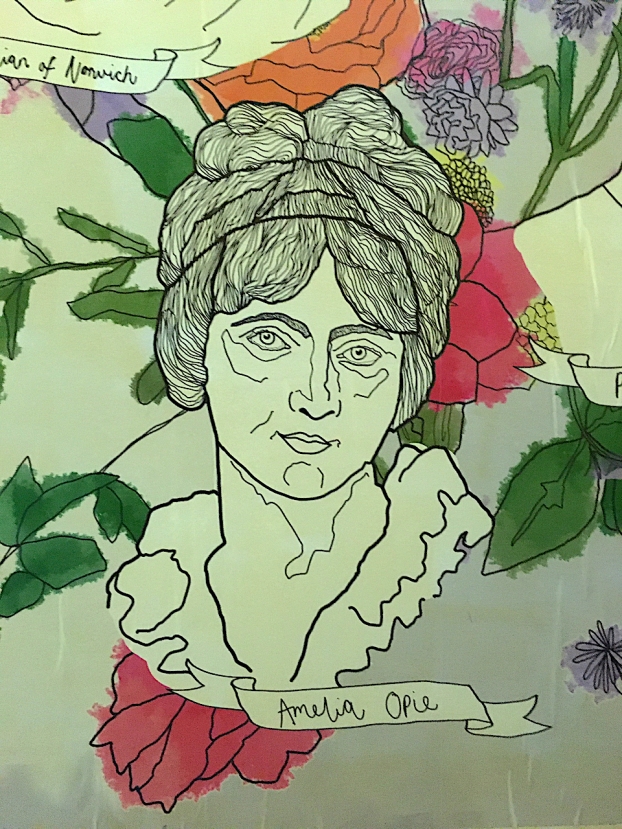

With its emphasis on the elaborate hair style the Turner etching may well have been the model for Amelia Opie on a new mural in Norwich Market. One hundred and sixty six years after her death it is this image of a vibrant, unbonneted woman that endures.

From a mural on the shutters of a stall in Norwich Market, by Lucie Knights for Norwich Norwich Business Improvement District (BID)

©Reggie Unthank 2020

This post is respectfully dedicated to Amelia Opie’s biographer Ann Farrant, who died in 2019.

Sources

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/03/15/three-norwich-women/

- Ann Farrant (2014). Amelia Opie: The Quaker Celebrity. Pub: JJG Publishing, Hindringham, Norfolk.

- Josephine Walpole (1997). Art and Artists of the Norwich School. Pub: Antique Collectors’ Club

- http://www.earlynorfolkphotographs.co.uk/Photographers/William%20Freeman/William_Freeman_photographer.html

- Tom Roast (2018). Ten Musical Families from Norwich. Pub: Gateway Music Norwich.

- Marc Girouard (1990). The English Town: A History of Urban Life. Pub: Yale University Press.

- Miss Thackeray (1883). A Book of Sibyls. Pub: Bernhard Tauchnitz, Leipzig. Mentioned in Anne Farrants biography.

Thanks to Cheryl Wood, archivist Norwich School, for showing me the Opie medallion. I am grateful to Victoria Nieto Felipe of Norwich BIDS for information on the mural of Amelia Opie in Norwich Market

great piece of detective work and beautifully written if I might add.

LikeLike

Too kind, Rosie

LikeLike

Wonderful – thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you Heather. Amelia Opie was such an interesting woman.

LikeLike

A very intriguing and engaging post, as usual. In the same year as the wonderful medallion, Tom Pocock has written that,”In 1851, when she was aged eighty-two, Amelia Opie visited the Great Exhibition in London, where she sighted another old lady in a wheelchair and promptly challenged her to a race.” My sort of lady!

LikeLike

She does seem like a free spirit. I’m impressed by how she made, and maintained, such a wide network of eminent friends through letter-writing.

LikeLike

Scholarly and readable – a difficult combination but Reggie you make it look so easy. Theo

LikeLike

Thank you Theo

LikeLike

A wonderful piece of research and writing. Really brings to life an interesting individual and the circles within which she moved. Hadn’t noticed the bust at the castle museum, but will now seek it out. Grant

LikeLike

With so much emphasis on our medieval treasures the period around the Regency doesn’t get much of a look-in but Norwich had a theatre and assembly rooms; it also had learned societies and Amelia Opie reminds us of the vigour of its intellectual life. I appreciate the comments Grant.

LikeLike

Fascinating, thanks! And just to show that there is no such thing as coincidence, I was in the V&A yesterday, and found this bust (http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O127117/lady-morgan-bust-david-dangers-pierre/) of Sydney Morgan by David d’Angers, of whom I had never heard before I read your piece on the train …

LikeLike

Thank you Caroline for this wonderful example of morphic resonance.

LikeLike

Yet again you have produced a splendid piece of research on one of Norwich’s ladies. It is always a pleasure to read your posts, not only for the research and information, but also for the quality of the language (and the grammer). Keep a’ troshin

Don Watson

LikeLike

I was grafted onto Norwich, not born here, so I had to resort to my ‘grammer-checker’ to look up ‘troshin’. Here’s what the Eastern Daily Press says: “The phrase derives from the practice of holding a horse’s rein hard to stop it from moving any further forward. Keep yew a troshin’ actually means “carry on with the threshing”, but is also commonly used in Norfolk as a way of saying goodbye and telling someone to take care of themselves.” Fabulous! Thank you Don.

LikeLike

Such an interesting woman! Thank you so much for all your research and the wonderfully illustrated post, Reggie.

LikeLike

Yes, what a fascinating woman. I enjoyed researching this post perhaps more than any other, Clare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s some heavy research you’ve put in there. The name of Opie caught my eye; memories of living in Norwich, and the cut through from Castle Meadow to London Street. Thank you for triggering several memories.

LikeLike

That cut-through has been greatly improved by a gelato shop. I wonder if Mrs Opie would have approved?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I doubt it. I remember something about sedan chairs. Was this where a sedan chair could be hired?

LikeLike

Yes, I think a plaque to that effect may still be there

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Norwich Banking Circle | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Parson Woodforde goes to market | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Parson Woodforde and the Learned Pig | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH