Tags

Catton Hall Norwich, Earlham Hall, Gurneys Bank, Harveys Bank, Keswick Hall Norwich, Whitlingham Hall

From the C16 onwards, when an influx of religious refugees from the Low Countries swelled the population by up to third, Norwich became a crowded city and those who had grown rich on the worsted industry began to move out. By moving to their grand houses in the country the wealthy not only marked their new social status but also escaped the epidemics of cholera, smallpox and typhoid that swept the city. They left behind urban space that became colonised by the poor who lived in hundreds of speculative shanties. These insanitary ‘yards’ or ‘courts’, accessed down an alleyway, were a defining feature of this city that lasted until the slum clearances of the C20 [1].

![Colegate Burrell's Yard view south [2030] 1937-10-09.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/colegate-burrells-yard-view-south-2030-1937-10-09.jpg?w=529)

In the heart of the former textile industry, Burrell’s Yard, off Colegate, 1937. ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

Old Catton was convenient for those who had business north of the river in Norwich-over-the-Water and what was once an agricultural village had, by the early C20, become ‘the best residential suburb adjoining Norwich’ [4]. This gentrification had begun in the mid-1700s when wool merchant Robert Rogers (Sheriff 1743, Mayor 1758) built Catton Place [4]. In 1816 this was to become the home of Samuel Bignold, son of the founder of Norwich Union.

![Catton Catton Place [0610] 1935-08-05.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/catton-catton-place-0610-1935-08-05.jpg?w=529)

‘The Firs’, formerly Catton Place, in 1935. ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

Portrait of Jeremiah Ives, Mayor of Norwich 1769, 1795, by Charles Catton. Presented by the yarn-makers of Norwich in gratitude for his opposition to an Act allowing the export of English wool [5].

‘Park Scene – View of Norwich – View in Catton Park’ by Humphry Repton (1752-1818). The cathedral spire can be seen between the trees. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM : 1936.32.2

The Harveys had a considerable presence in Old Catton: Thomas Harvey built Catton House but there was also Robert Harvey at The Grange and Jeremiah Ives Harvey at Eastwood [4].

To the north of Norwich on Faden’s map of 1797 ©Andrew Macnair. The land of J Ives Esquire is underlined in yellow. Mr T Harvey’s house in parkland is starred while Mr R Harvey and Mr Harvey owned land to the east (underlined).

But the Harvey who built Catton House was the one who married Ann Twiss – daughter of an English merchant from Rotterdam – and whose collection of Dutch paintings had a formative influence on the co-founder of the Norwich Society of Artists, John Crome (see recent post [7]).

Catton House post-1945. Courtesy of the Old Catton Society

The Gurneys also had a presence in Catton: in 1854 Catton Hall was bought by the seriously rich John Henry Gurney Snr who had inherited the bulk of the fortune accumulated by Hudson Gurney (1775-1864) of Keswick Hall (see below). The Gurneys were Quaker weavers who, through an ‘extended cousinhood’ of alliances and partnerships, formed the country’s largest banking network outside London [3,8].

Financial intermediaries in the Norwich woollen trade, John and Henry Gurney established Gurney’s Norwich Bank in 1770. In 1778, Henry’s son Bartlett inherited the bank that he ran with the help of two cousins, Richard and Joseph Gurney. Their premises were in a former wine merchant’s whose cellars proved useful for housing the safes, protected by a mastiff and a blunderbuss. Gurneys Bank was near the red well on Redwell Plain, which was renamed Bank Plain.

Gurneys, Birkbeck, Barclay and Buxton Bank on Bank Plain Norwich in the 1920s, here re-badged as Barclays Bank. ©Barclays Group Archives. Astonishingly, the same ornate lamp-post on the left still stands in the same spot (see right).

In 1896 the bank became amalgamated under the Barclays name and the present grand banking hall was built on the site in 1927 [8]. In the C19, their London branch became ‘the world’s greatest bill-discounting house’, allowing a character in a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta to sing, ‘I became as rich as the Gurneys‘. Nevertheless, in 1866 they went bust with £11,000,000 liabilities. Although this ruined several Gurneys the Norwich branch escaped significant damage [3,8].

The ‘new’ Barclays Bank built 1927, now housing ‘Open’ Youth Trust

Influenced by the Great Exhibition’s Crystal Palace, Gurney extended Catton Hall with a cast-iron Camellia House designed by local architect Edward Boardman and manufactured in Boulton & Paul’s Norwich factory. The fine cupola was removed in WWII to prevent enemy planes using it as a landmark on the way to RAF St Faith’s (now Norwich Airport) [2,4].

Catton Hall. The original cupola on the Camellia House is illustrated in the old postcard below, courtesy of the Old Catton Society.

John Henry Gurney Snr was married to Mary Jary who ran off with one of the grooms.

Courtesy of ‘Hethersett Heritage’ by the Hethersett Society

… and, to compound JH Gurney’s woes, the bank in which he was a major shareholder (Overend, Gurney & Co.) went bust in May 1866. This triggered ‘Black Friday’ in the City and led to him selling the Hall to his cousin, Samuel Gurney Buxton, a banker at Barclays [3,4]. In 1896, Gurneys Bank was to join 10 other private banks controlled by Quakers, to form Barclays Bank.

Mary Jary Gurney had come from Thickthorn Hall, a few miles south of Norwich at Hethersett. She had lived in this early C19 house that passed to Richard Hanbury Gurney when the owner defaulted on his mortgage. It stayed in the Gurney family until the 1930s when Alan Rees Colman, director of Colmans and second son of Russell Colman of Crown Point, bought the hall.

Thickthorn Hall. Courtesy of Cathie Piccolo

In addition to Catton and Thickthorn the wider Gurney family also had country houses ringing the city – at Colney, Earlham, Easton, Keswick Hall and Sprowston.

Clockwise from Catton Hall (Gurney) at 12 o’clock, banking families were associated with: Sprowston Hall (Gurney), Whitlingham Hall (Harvey), Crown Point (Harvey), Keswick Hall (Gurney), Eaton Hall (mistakenly labelled Easton Hall by Faden; Easton Lodge was briefly owned by a Gurney but is actually a few miles west), Earlham Hall (Gurney) and Colney Hall (Barclay). From Faden’s Map of 1797 ©Andrew Macnair.

The mid-C16 Sprowston Hall was acquired by the Gurneys in 1869 – bought by John Gurney, the eldest son of John Gurney of Earlham Hall (see below) [2]. Gurney employed Wymondham architect Thomas Jeckyll to re-design it in an Elizabethan Revival style. Jeckyll, however, could not resist inserting an of-the-moment gate in the Aesthetic Style that he helped champion.

Jeckyll’s ‘japonaise’ gate at Sprowston Manor. See previous post.

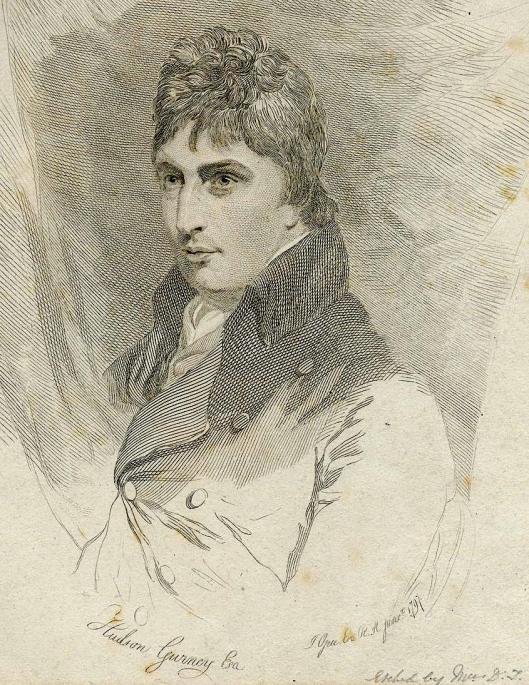

But if we’re following the money it’s impossible to avoid the gravitational pull of Keswick, south of Norwich. The worsted weaver Joseph Gurney came to Keswick Old Hall in 1747 but when the fabulously wealthy Hudson Gurney (who inherited brewing as well as banking money) took over the estate in 1811 he built a new Keswick Hall in the Regency style [2].

The ‘dashing smart’ Hudson Gurney in an etching by Mrs Dawson Turner from a painting by John Opie RA. Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM: 1832.39.1

![Keswick Hall south front [6606] 1990-04-30.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/keswick-hall-south-front-6606-1990-04-30.jpg?w=529)

Keswick Hall, south front in 1990. ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

The 1892 Diocesan training college for school mistresses on College Road, Norwich, was bombed in WWII and the students moved to Keswick Hall

Earlham Hall, just west of the city, is another Gurney residence now associated with education [2]. For over a century the house was rented from the Bacon family during which time it was occupied by the banker John Gurney (1749-1809) and his family. Not all of his 13 children survived but Samuel, Daniel and Joseph John lived on to become bankers. Joseph John Gurney was also a Quaker minister and, like his sister Elizabeth Fry (née Gurney), was active in social and prison reform.

Earlham Hall as it was in the early C19. Now, much changed, it houses the UEA Law School. Courtesy landscape.uea

The easternmost house I underlined on Faden’s map is Whitlingham Hall on the Crown Point Estate. The Hall was built for Sir Robert Harvey Harvey 1st Baronet by architect H E Coe, a pupil of Sir George Gilbert Scott. The local practice of Edward Boardman and Son supervised the building of this large Elizabethan-Revival mansion with its spectacular ornamental conservatory [9].

Whitlingham Hall, which superseded Crown Point Hall. ©Rightmove

Five years later, as one of the proprietors of what began as Hudson and Hatfield’s Bank, Harvey was to build the grand Classically-styled Norwich Crown Bank; this was on Agricultural Hall Plain, within sight of Gurneys’ (later, Barclays) Bank on Bank Plain [10]. Unfortunately, Sir Robert had been speculating on the stock exchange and tried to disguise his heavy losses as debts owed by fictitious customers. When the scandal broke in 1870 Harvey shot himself. Somewhat ironically, in view of their own recent financial uncertainty, Gurneys Bank bought the goodwill of the Crown Bank in order to quell local panic [3]. The Crown Point Estate was sold to JJ Colman and in 1955 it became Whitlingham Hospital, now private apartments.

Norwich Crown Bank

The name ‘crown’ associated with this building is sometimes thought to be associated with its later use as the city’s Head Post Office (until 1969).

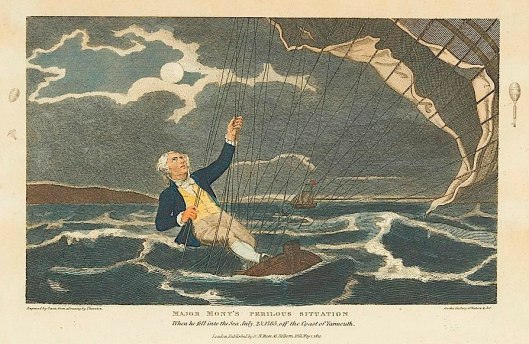

The name, however, traces back to Major John Money who built Crown Point Hall, which was torn down when Sir Robert Harvey built Whitlingham Hall [2]. Money served in the Army during the North American Campaign [2] where he was based at Fort Crown Point – “the greatest British military installation ever raised in North America.” [11]. You may remember Major Money from a previous post [12] that describes his perilous balloon flight of 1785 when he took off from Quantrell’s Pleasure Garden (near Sainsbury’s on Queens Road); he landed in the sea off Yarmouth from which he was rescued several hours later.

Bonus track: The Harvey family portrait [13]

You know that dream where you meet all your ancestors in some celestial picnic spot; you know, grandparents, distant aunts and uncles and a posse of strangely familiar faces? Well, here it is, several blog posts rolled into one. There’s Robert Harvey who founded the family bank (#3 in the portrait). And there’s John Harvey (#5) from the Street Names post [14] who gave his name to Harvey Lane; he also appeared in the Norwich School of Painters post in Stannard’s painting, Thorpe Water Frolic [7]. There’s even Charles Harvey MP (#6) who took the surname of his uncle Savill Onley in order to secure an inheritance, as we saw in Street Names [14], together with his son Onley Savill Onley. (#7) And don’t forget that Onley became an Unthank name (hence, Onley Street) through marriage [15]. These are just some of the unspoken connections in the portrait by Norwich School artist Joseph Clover – a friend of Amelia Opie’s husband John who we encountered in the previous post, Behind Mrs Opie’s Medallion [16].

The Harvey Family of Norwich, by Joseph Clover c 1821. Courtesy of Norwich Castle Museum and At Gallery NWHCM: 1985.435. 1= Robert Harvey ‘Father of the City’ (1679-1773); 2= Sir Robert Harvey Harvey; 3=Genl Sir Robert Harvey b.1785, founder of Harvey’s Bank; 4=Robert Harvey of Catton and St Clements ?1730-1816; 5= John Harvey of Thorpe Lodge 1775-1842; 6= Charles Harvey who took the name of Savill Onley 1756-1843; 7= Onley Savill Onley d.1890; 8= Roger Kerrison of Brooke House, Norfolk. Father-in-law of John Harvey (#5) and bank owner 1740-1808.

©Reggie Unthank 2020

Sources

- Frances and Michael Holmes (2015). The Old Courts and Yards of Norwich. Pub: Norwich Heritage Projects.

- David Clarke (2011). The Country Houses of Norfolk. Part Three: The City and Suburbs. Pub: Geo R Reeve Ltd, Wymondham.

- Roger Ryan (2004). Banking and Insurance. In, ‘Norwich Since 1550’ by Carol Rawcliffe and Richard Wilson. Pub: Hambledon and London.

- Old Catton Society (2010). Historic Houses of Old Catton. Pub: Catton Print, Norwich.

- http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk/monuments/Jeremiah%20Ives%201729%20-%201805/Jeremiah%20Ives%20younger%201729.shtm

- http://www.cattonpark.com/about/park-history.html

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/09/15/the-norwich-school-of-painters/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gurney%27s_Bank

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1001480

- AD Bayne (1869). A Comprehensive History of Norwich. Pub: Jarrolds, Norwich. Now available online:https://www.gutenberg.org/files/44568/44568-h/44568-h.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Crown_Point

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/01/15/pleasure-gardens/

- Andrew Moore and Charlotte Crawley (1992). Family and Friends: A Regional Survey of British Portraiture. Pub: London: HMSO and Norwich: Norfolk Museums Service.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/10/15/street-names/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/01/30/colonel-unthank-and-the-golden-triangle/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2020/01/15/behind-mrs-opies-medallion/

Thanks to David Clarke of City Bookshop, Norwich, for his advice; his Country Houses of Norfolk is the standard work. I am grateful to Dr Giorgia Bottinelli and Jo Warr of Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery for providing the information on the Harvey portrait. Thanks also to Ray Jones, archivist to the Old Catton Society for providing images and to Cathy Piccolo for information on, and the photo of, Thickthorn Hall.

Love it

LikeLike

Much enjoyed reading about these Norwich/Norfolk families, Reggie.

LikeLike

Thank you Eva

LikeLike

Fascinating, as ever, Reggie. The research, the writing and the illustrations in these posts never fail to entertain and inform. Keep them coming.

LikeLike

I had expected to see a greater diversity of trades pushed out to the edges and was surprised to find the banking monoculture. Thank you for the kind comments Richard.

LikeLike

The monoculture point is interesting. But so is the subsequent shift in ownership of some properties: for instance, I think I am right in saying that Thickthorn Hall, which you record as passing from Gurney ownership to the Colman family, subsequently became the residence of Lord Mackintosh (of the sweets manufacturers).

.

LikeLike

That’s correct Richard. Might the shift in ownership reflect the diversification of Victorian wealth creation, especially at a time when the Norwich woollen trade had gone into a permanent decline? For example, in the late C19/early C20 Chamberlin the local draper bought Colney Hall, Colmans the mustard-makers moved into Crown Point; a member of the Lacon brewing family moved into Dunston Hall etc etc.

LikeLike

Another fascinating post. I particularly liked the portrait of Hudson Gurney with his artlessly tousled coiffure. He could be a character in an Austen novel

LikeLike

Isn’t he the Regency dandy! Not sure how this squared with his Quakerism.

LikeLike

Another great piece of research pulling together a lot of information about an extensive family!

LikeLike

At the outset I had little idea this would turn into a post on Norwich bankers. This city is endlessly fascinating.

LikeLike

Yet again you have excelled yourself. How interconnected a few Norwich families were by the end of the 19th C. – family occasions must have been enormous.

My mother spoke of Sunday School outings to Catton Hall in the early 20th C.

A great grandfather lost money in the Crown Bank failure (according to family stories)

Don Watson

LikeLike

Your family connection with the Crown Bank collapse is fascinating, Don. I don’t suppose the family have access to any paperwork relating to this?

LikeLike

No documents – it is a tale I heard as a child , referring to my mother’s maternal grandfather

LikeLike

Wonderful! All those banking magnates and their country estates! Beautifully illustrated, Reggie – thank you.

LikeLike

Hello Clare, And to think that the Norwich banks, which gave rise to one of this country’s largest (Barclays), emerged out of the fair dealing approach of the Quakers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some more exceptional research Reggie, as always. I remember spending many happy hours at Keswick Hall in the early ’60’s visiting my Sunday School teacher who was a trainee living there.

LikeLike

Hello James, I live so near Keswick Hall but have never been inside. Does much of the original fabric remain?

LikeLike

The comprehensive rigour of the research is always matched by the high quality of your presentation; keep it up, please.

LikeLike

Comments like this make it all worthwhile. Much appreciated, Martin.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Plains of Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Revolutionary Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Georgian Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

I believe Catton Hall was inherited by Jeremiah Ives, given to his wife in his father-in-law’s will.

Jeremiah Ives of Catton Hall had a cousin (Jeremiah Heacock Ives) who died young, leaving his son (also Jeremiah Ives, dates 1777-1729) in the care of the grandfather (Jeremiah Ives, dates 1729-1805) who had been in business with the Jeremiah Ives of Catton Hall’s father (also named Jeremiah Ives). It’s confusing. Their firm was J&J Ives. Anyway, this Jeremiah Ives who lived from 1777 to 1729 went into the banking business with one of the Barclays. He was the bank’s general manager in the 1820s. Like Sir Robert Harvey did 41 years later, he shot himself around the time that the Barclay’s Bank suffered a loss. However, the 1829 loss was not so much of a scandal, and he could easily have covered the loss with his personal money, but I think (this is from family oral history; I’m a direct descendant) he was a bit insecure about his reputation and suffered from moods anyway, and felt responsible for the loss because he had confidently recommended making the loan(s) that were lost.

Those Ives and Harveys are hard to keep straight. There is a painting by Philip Reinagle (1749-1833) “Members of the Carrow Abbey Hunt” where three of the six members (Timothy Tompson, Robert Harvey, and Jeremiah Ives) depicted are all my direct ancestors (their grandchildren and great-grandchildren intermarried).

LikeLiked by 1 person

My source was ambivalent about how Jeremiah Ives came to own Catton Hall. Thank you, as a descendent, for disentangling the family lineage.

LikeLiked by 1 person