I’ve mentioned James Minns, ‘Carver’, a few times in these pages, always as an appendage to well-known local architects like George Skipper, Thomas Jeckyll or Edward Boardman, but I keep stumbling across his work and felt it was time that ‘Norfolk’s Grinling Gibbons’ [1] had a post of his own.

James Minns. From the East Anglian Magazine [1]

James Benjamin Shingles Minns – son of Sarah Shingles and James William Minns, cabinetmaker – was born in Lakenham, Norwich, at the beginning of 1825. ‘Minns’ is not uncommon in East Anglia and can be traced back to the Protestant Dutch ‘Strangers’ who brought the name here in the C16 , when it was Mins [2]. The 1841 census shows that James had two sisters; he also had two brothers, both of whom shared their father’s trade as cabinetmaker. Young James had woodworking in his blood.

E.C. LeGrice tells us that Minns lived in a house on Westlegate [1]. This house was ‘demolished – with several others – to make room for a modern block of shops’ but an old shop in that cluster ‘still remains … under the very shadow of the tower of All Saints Church’ [1]. That remaining building sounds very much like the thatched building below.

![Westlegate 20 Barking Dickey Inn COLOUR [2957] 1939-04-12.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/westlegate-20-barking-dickey-inn-colour-2957-1939-04-12.jpg)

Westlegate 1939, under the shadow of All Saints tower. The thatched building was once The Barking Dicky PH, now Waring’s Lifestore. The adjacent building (left) was demolished to make way for Westlegate Tower. ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

(Just after this article was posted, David Vincent sent this photograph of Westlegate in 1890, as Minns would have known it before the street widening)

Westlegate 1890, courtesy of David Vincent.

The census gives no clue to when Minns lived here but in 1851 he was living as a ‘visitor’ in the house of dressmaker Frances Scales (widow) at 180 Kensington Place, near the junction of Queens Road and City Road. Genealogical records show that Minns married Elizabeth Emily Thompson in 1858 and, according to the 1861 census, was living at The Steam Packet public house. Confusingly, three Norwich pubs shared the name of the Steam Packet (a small boat regularly plying between ports) but, since a William John Shingles Thompson is listed as a proprietor of The Steam Packet in King Street [3], it would appear that this is where James Minns was living with his Thompson in-laws.

![King St 191 Ferry Boat Inn [1286] 1936-08-16.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/king-st-191-ferry-boat-inn-1286-1936-08-16.jpg)

The Ferry Boat Inn (1936), formerly The Steam Packet. 191 King Street ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

Papers at the Record Office indicate that in 1864, James Minns – listed as ‘wood and stone carver’ – bought two ‘recently erected cottages, part of a row of eight’, for £150 from the builder Edward Burton [4] . Numbers 9 and 11 were in Arthur Street, a cul-de-sac off Mariner’s Lane, which at that time connected Ber Street on the high ridge down to King Street on the riverside. So Minns moved up the hill from his in-laws’ riverside pub

Mariners Lane once connected Ber Street (red) with King Street on which the Steam Packet is marked with a star. Minns lived in a block of 8 new houses on Arthur Street (purple). 1907 OS map courtesy of https://maps.nls.uk/.

Amongst Minns’ conveyances in the Norfolk Record Office there is an interesting aside: in 1876, the Norwich and Norfolk Provident Permanent Benefit Building Society turned out not to be so permanent and went into liquidation. Minns was allowed by the liquidator, Samuel Gulley, to redeem his mortgage for £20-8s-5d.

From 1851 to 1901 Minns described himself in public records with the plain English word ‘carver’: ‘carver in wood’, ‘wood carver’ and ‘wood and stone carver’. In 1881 there was a lapse when he used the Frenchified ‘sculptor’ but by 1891 and 1901 he was a ‘carver’ once more. This down-to-earth description of his profession was consistent with E.C. LeGrice’s description of a ‘shy and diffident woodcarver (who) had great difficulty in courteously excusing himself from being presented to his royal admirer, King Edward the Seventh’ [1].

Minn’s unflowing signature. Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service [4]

James Minns was evidently no scholar, his only formal instruction being ‘a little general training which he received at the old (Norwich) School of Art when he was a youth’ [1]. An article in the Eastern Daily Press of 1904 confirmed, ‘He was no laborious school-product.’ [5]. It must have given him deep satisfaction, therefore, to have returned in his mid-sixties as Instructor in Wood Carving [6]. This was about 1890, at a time when the School of Art had rooms in the Free Library on St Andrew’s Street. In 1857 an extra storey had been added to accommodate the School: ‘On the third floor are two large rooms for the School of Art, with domed roofs and ample skylights, and four smaller apartments for classes are also provided [6].’

The Norwich Free Library at the junction of St Andrew’s Street and Duke Street. James Minns gave instruction on the third floor. (From ref [7])

This arrangement proved unsatisfactory, for a few decades later a student committee of six men and four women petitioned for a separate School of Art. One of the petitioners was J.W. Minns. This was James’ son John William who, like his father, became a Norwich Freeman in his twenties; he also described himself as ‘carver’ (1887) [8].

Despite his retiring nature James Minns was confident enough to instruct students in technical matters – after all, he had about 50 years of experience to pass on. He also had sufficient belief in the artistic merit of his work to submit – successfully – a carved panel to the Royal Academy’s 1897 Summer Exhibition.

11 Mariner’s Lane is suggested to have been his workshop [9]. (2017 is the catalogue number)

The Royal Academy has no photograph of this entry and for some time I had no idea of the delicacy of his work until I came across this example in LeGrice’s brief essay on Minns [1].

James Minns’ Bullfinch panel, undated. © 1958 E.C.LeGrice.

Could this be the same bullfinch panel listed in the Norfolk Museums Collections? There is no image of that panel on the site but Samantha Johns generously tracked it down and photographed it for me, revealing this to be quite a different bunch of bullfinches (for which the collective noun is, surprisingly, a ‘bellowing’).

Bullfinch Panel by James Minns. NWHCM 1897.55. Photo courtesy of Sam Johns.

In 1958 LeGrice [1] mentioned that several Minns panels were in the possession of the Colman family. Several still are and I was kindly shown the following three panels of intricate, deeply undercut birds and foliage (although the curved glass posed problems for this amateur photographer). Amongst them was the superb bullfinch panel featured in LeGrice’s article [1].

Birds nesting amongst the larch. The Bullfinch Panel. Courtesy of James Colman

Bird panel, courtesy of James Colman

Woodcock, courtesy of Matthew Colman

Norwich Castle Museum holds a further Minns bird carving under glass.

‘Pigeon’ by James Minns 1877. Norfolk Museums Service NWHCM: 1924.9

Minns’ success at the Royal Academy was not an isolated one for, as an obituary noted, ‘In competitions both at home and on the Continent he carried off some of the chief trophies of his time’ [5]. The carvings under glass quite likely represent his exhibition pieces. These high points of his artistic output contrasted with his bread-and-butter work at Gunton’s brickyard in Old Costessey. Over a long period – perhaps decades – he made moulds for decorative bricks that were turned out in their hundreds (see previous post on ‘Fancy Bricks’ [10]).

Cosseyware chimney bricks. The rose and shamrock are from the Patriotic range. Provided by Andy Maule.

However, one-off terracotta panels, like those at St Bennet’s – a private house in Cromer (1893) – gave Minns the opportunity to be more creative.

James Minns’ best known panels decorate the red brick building, part of Jarrold Department Store on London Street. Until 1946 this housed the offices of the architect, George Skipper. Although Skipper wasn’t supposed to advertise his architectural practice he installed a panel illustrating himself with three of his Norwich buildings in the background: The Daily Standard Office of 1899 in St Giles Street; The Norwich Union Building of 1904; and Commercial Chambers in Red Lion Street, 1901 [11].

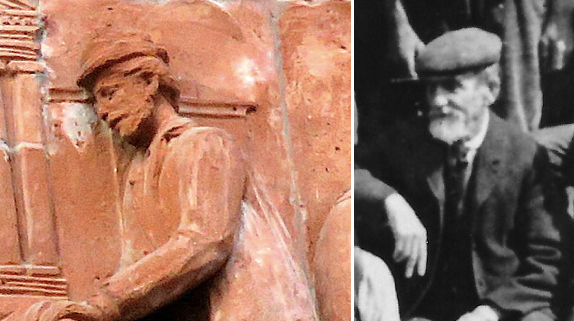

In this tableau, a top-hatted Skipper points to a shield presented by a bearded workman in a dust coat, with younger carvers to the rear. The older man presenting the shield would have been the senior craftsman and, as such, is likely to be James Minns himself.

The head craftsman (left) and James Minns (see below)

Richard Barnes informs me that the terracotta panels on the front of Skipper’s office were being completed around the time (1904 [12]) that work was starting on another of Skipper’s projects – the building of Jarrold Department Store, literally next door. Because James Minns died in 1904, Richard wonders if much of the work might have been done by Minns’ son John. We cannot know for sure but it could explain the rare sighting of this shy carver.

As we saw in a previous post, father and son were both associated with the Costessey brickyard [10].

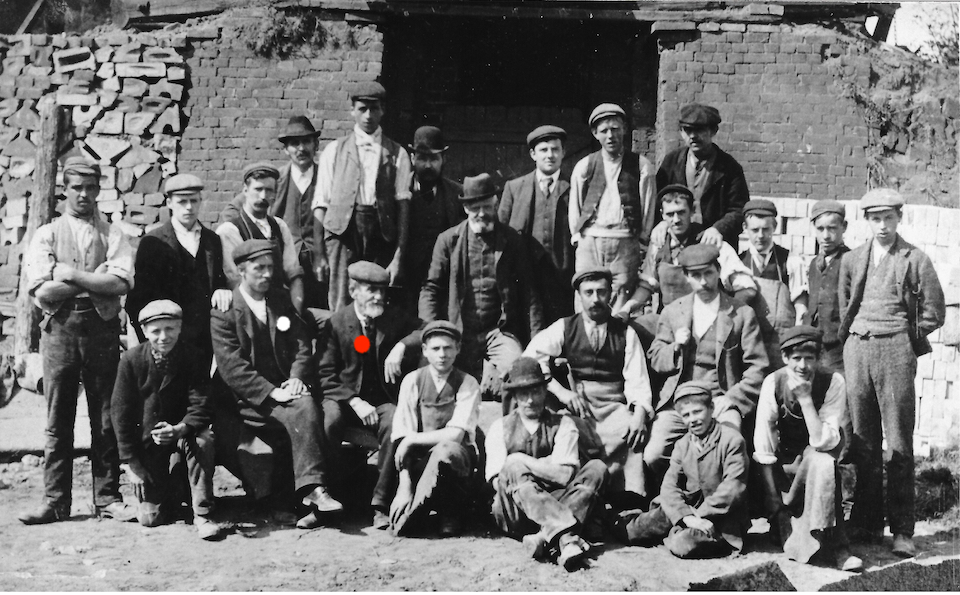

Workers at Gunton’s brickyard ca 1900 named by Peter Mann. James Minns (red dot) and John Minns (white dot) were labelled ‘Carvers of Norwich’, Photo courtesy of Paul Cooper

In his capacity as builder, George Gunton renovated the church at St Michael the Archangel, Booton, about six miles from Costessey. Minns carved the huge whirring wooden angels flying in the nave.

I haven’t been able to find objects sculpted by Minns in bronze although the St Michael over the door at Booton church is tentatively assigned to him on the racns website [11]. One specialist suggested that the sculptor was uncomfortable working with bronze [13] – perhaps someone like Minns, more used to subtractive carving than building up a maquette for casting? (See addendum at the end of this post).

Minns’ employment with Guntons was sufficiently accommodating that he could work on his own projects for local architects and designers in materials other than baked clay. For example, Minns worked with Thomas Jeckyll [14] on the Norfolk Gates – an exhibition piece by the Norwich foundry of Barnard Bishop and Barnards (1862) that was then given as a wedding gift by the people of Norfolk to the Prince (later, King Edward VII) and Princess of Wales at Sandringham [15]. Hand-wrought ironwork dominates but the piers and their base panels were cast and this is where Minns made his contribution, bringing him to the attention of the future king.

Left: The Norwich coat of arms, cast iron, from the Norfolk Gates. Image ©www.racns.co.uk. Right: carved wooden panel being sold by http://www.hillhouse-antiques.co.uk. A similar wood carving of the Norwich coat of arms, labelled “pattern for cast iron”, which is held in the Norfolk Museums Collections (NWHCM: 1969.59.1), is attributed to James Minns.

Over the years, Jeckyll worked extensively for the Boileau family at Ketteringham, including house, church, farmhouses and the estate in general. Minns is known to have carved the figures on the church tower [17] and he is likely to have provided other touches around the village.

About 1850, Jeckyll designed the well outside ‘Wellgate’ in Low Street, Ketteringham; it bears the Boileau arms.

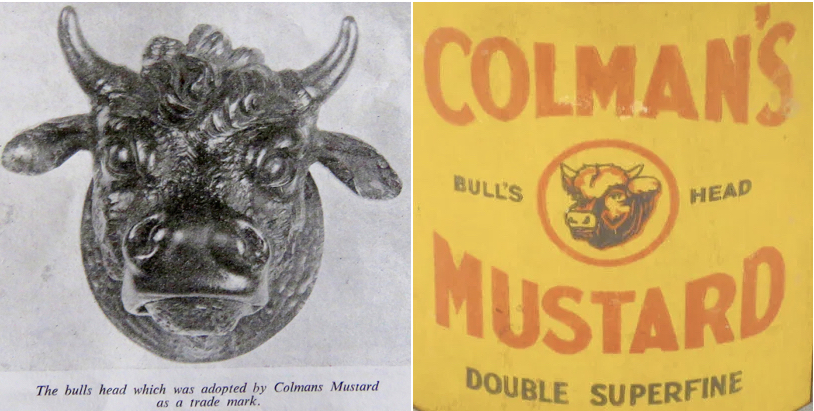

James Minns also designed this logo for Colman’s mustard.

The bull’s head, from LeGrice’s article on Minns [1]. ©E.C.LeGrice

He also did much of the carving in the Colman’s home at Carrow House. Helen C. Colman reminisced:

“My Father and Mother returned to Carrow House on June 7th 1861 though it was still more or less in the hands of workmen … but the wood carving in oak in the Library … was for the most part done during the ‘sixties … it was nearly all carved locally, and much of it by James Minns.” [16].

Dated 1862, the fireplace in the Old Library at Carrow House is richly carved with birds, flowers and foliage. The four human heads, however, were said by Helen Colman to be ‘carved by someone from a distance’ [16]); i.e., not Minns.

Mantelpiece in the Old Library at Carrow House carved by James Minns, except the four small heads. Photos courtesy of Sam Johns, Norfolk Museums Service

The remodelling of Carrow House is thought to have been carried out by Edward Boardman [17] (whose son was to marry into the Colman family) and he would have been familiar with James Minns. Indeed, a footnote on Boardman’s plans for the 1891 renovation of the Manor House at Catton specifically names the Minns family of carvers [18, 19].

The cat and tun (barrel) rebus, carved by the Minns family, on the south door at Catton Manor House, copies the older carving on the east side. Courtesy of Robert Radford. Photo: Ray Jones, Old Catton Society

Although the Colman family were Nonconformist they supported church-going amongst their workers; at St Andrew’s Trowse – a short walk from Colman’s Carrow Works – they donated a reredos of the Last Supper. It is said to be ‘a copy of an Italian masterpiece, carved by James Minns of Lakenham’ and was dedicated in 1905, a year after Minns died [20].

The Last Supper is often depicted with all figures aligned on the far side of the table, school-photograph style. Here, a second row of figures at front increases the depth. I can only find similar versions in Northern European panels. Can you identify the original?

George Skipper’s masterwork was Surrey House, headquarters of Norwich Union (now Aviva) in Surrey Street, and was completed in 1904. A 2008 conservation plan for Aviva states that H.H. Martyn & Co of Cheltenham, who specialised in woodwork and panelling, were assisted by James Minns of 11 Arthur Street, Norwich, “including the carved figures over the main doorway” [21]. The use of Minns’ correct address lends credibility although large carvings of women lolling on the pediment aren’t the usual Minns territory.

More in keeping with the skilfully carved foliage we saw in his bird panels are the baroque swags of fruit and flowers hanging on the mahogany panelling. These are reminiscent of Grinling Gibbons’ work and Le Grice did, after all, confer the title of ‘Norfolk’s Grinling Gibbons’ on Minns. On the other hand, reproductions of Grinling Gibbons carvings were a speciality of Martyn’s of Cheltenham [22] so we await corroboration that James Minns was the actual carver.

Left: Intricate carving from the boardroom, Surrey House. Right: Grinling Gibbons (1648-1721) Hampton Court Palace (by Camster2, Wikipedia, Creative Commons licence).

James Minns died on the 6th of August 1904. His death certificate gives the cause of death as cardiac syncope; he also had senile decay, which makes one wonder if this affected the quality of his work in the latter years and whether his son had to do work on his behalf. James Benjamin Shingles Minns left £200 to his son John plus ‘effects’ – perhaps his tools. A few days later, the Eastern Daily Press wrote this tribute: “There passed away this week in Norwich a brilliant practitioner of a delightful form of art. As a wood carver Mr Minns was in the utmost sense of that term a genius [5].”

©2020 Reggie Unthank

If you know anything about the life and works of James Minns, especially previously unrecorded carvings, please get in touch via the Contact link. Comments will not be published without your approval.

Sources

- E.C.LeGrice (1958). James Minns: Norfolk’s Grinling Gibbons. East Anglian Magazine vol 18, No2, December.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/08/15/going-dutch-the-norwich-strangers/

- http://www.norfolkpubs.co.uk/norwich/snorwich/nchsp4.htm

- Norfolk Record Office: N/TC/D1/100/5-12

- Under ‘Local Topics’, an article written in the week of Minn’s death. Eastern Daily Press 12th August 1904.

- Marjorie Allthorpe-Guyton with John Steven (1982). ‘A Happy Eye’: A School of Art in Norwich 1845-1982. Pub: Jarrold & Sons Ltd, Norwich.

- George A. Stephen (1917). Three Centuries of a City Library. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19804/19804-h/19804-h.htm

- http://nfro.norwichfreemen.org.uk/detail/11785/

- https://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/person.php?id=ann_1283258555

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/05/05/fancy-bricks/

- http://racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp

- David Bussey and Eleanor Martin (2012).The Architects of Norwich: George John Skipper, 1856-1948. Norwich Society publication.

- http://www.racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp?action=getsurvey&id=1065

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/04/15/thomas-jeckyll-the-boileau-family/

- http://racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp?action=getsurvey&id=540

- Helen C. Colman (1922) “Carrow House Past and Present”. In, Carrow Works Magazine pp51-54.

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (2002). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- Ray Jones of the Old Catton Society, personal communication.

- https://norfolktalesmyths.com/2020/02/11/adventures-of-the-old-catton-village-sign

- https://www.trowsechurch.co.uk/page/43/about-our-church-2

- 2008 Aviva Conservation Management Plan mentions ‘H.H. Martyn & Co. Ltd., of Cheltenham – specialist woodwork and panelling, assisted by James Minns of 11 Arthur Street, Norwich (boardroom and committee rooms woodwork including the carved figures over the main doorway)’. Courtesy of Aviva Archivist Thomas Barnes.

- https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/H._H._Martyn

Thanks. I am grateful to: Peter Mann, Paul Cooper and Brian Gage who provided information on the Costessey brickyard; Richard Barnes for information on Jeckyll; Thomas Barnes, Archivist at Aviva for access and information; Robert Radford, owner of Catton Old Hall and Ray Jones of the Old Catton Society; Sue Roe for genealogy; Hill House Antiques & Decorative Arts Ltd; Byron Cooke and Mary Perrott for access to Carrow House; Samantha Johns of Norfolk Museums Service, for photographing Minns’ work; and Matthew Colman and James Colman for allowing me to photograph three superb examples of Minns’ framed bird carvings. Evelyn Simak provided James Minns’ death certificate.

Addendum 30/11/2020

Recently revisiting the carving of the Prince of Wales feathers on the Agricultural Hall I had the impression that I’d seen this way of handling feathers before. Comparison of the brick feathers with the wings on the Booton bronze shows they share stylistic traits: a rather fluffy treatment of the top of the feather and wing compared to the transverse barbs below. They could well be by the same carver/sculptor.

Fascinating to see through the research what a settled Norwich life Minns led. The historic Kings Street area was definitely his patch. Thanks Reggie

LikeLike

A Norwich working man to be proud of. The King Street area does seem to have been home to a community of craftsmen. Thank you Sue.

LikeLike

Fascinating…and what a prolific range of beautiful work remains as a legacy.

LikeLike

I agree, Michael, the range of his work is impressive. We see so much of it everyday in Norwich, in the Gunton’s fancy bricks, but it would be good to find more examples of his detailed wood carvings.

LikeLike

I believe there is some of his Gunton brickwork at The Hotel de Paris in Cromer, and that would have been through his association with George Skipper.

LikeLike

Thank you Michael. I had intended to gather previous mentions of Minns and Skipper into the present blog post but it got too unwieldy. A few other mentions of Cromer can be found in https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/02/15/the-flamboyant-mr-skipper/

LikeLike

Another fascinating article – thanks so much. I wish now I had taken note of the carved reredos in St Andrew’s Trowse Newton (said to be the last work of Minns?) but I couldn’t get past the amazing larger than life size wooden figures which you would know: they are part of the pulpit and may have come from a Dutch organ (apparently); I read that they were presented by Russell J Colman in 1902. As to the figures in the foreground of the Minns carving there, I don’t know the answer except to say that the standing figure somehow reminds me of the terracotta carvings in Bologna’s Santa Maria della Vita.

LikeLike

Hi Pamela, Those Italian carvings are superb and certainly have depth. I must admit, though, that the figures in the Trowse reredos look slightly wooden (no pun intended) and, since this is a late work, wonder if they might have been carved by son John.

LikeLike

Thank you Reggie – yet another fascinating read!

LikeLike

Thanks for alerting me to the link between Minns and the work at Old Catton.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A lovely and very interesting read. I had heard about Minns and have unconsciously known his work through researching George Skipper.

I have a copy of an 1890 view of Westlegate that shows all the properties to All Saints church, including the Light Horseman public Horse, which through a rather poorly painted sign became known as the Barking Dicky. (I have been unable to attach a copy)

LikeLike

I would love to see that photograph, David. Perhaps we could arrange that?

LikeLike

Another really excellent and interesting article which links together so many different aspects of Norwich history through one man. I hope all or some of your articles will one day appear as a book.

LikeLike

Funnily enough, Richard, I’ve been writing essays based on the blog today. It should keep me occupied as I go into social-isolation.

LikeLike

An excellent exploration of the life and work of a man who deserves to rank with

Cotman and Crome as an artist. His work in the Costessey brickyard is displayed in many places in Norwich and even the most familiar never fails to brighten the day for me.

Don Watson

LikeLike

I agree, Don. It IS good to see Minns’ fancy bricks around the city but his exhibition-grade wood carvings show that he was capable of so much more.

LikeLike

Another interesting and well-researched post, Reggie.

LikeLike

Thank you Clare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Norwich Department Stores | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Dear Colonel Unthank….

As per usual I spend hours reading your splendid web pages and research on Norwich. I’ve learned so much from it. James Minns always fascinates me and I admire his work while on security duties at Carrow Abbey. One thing I have not found in your article is where James is buried? I found several Minns in the ‘Rosary’.. Is he buried there?

Kind Regards to you Sir.

Julian A Hanwell.

LikeLike

You have some fine Minns carvings at Carrow Abbey, Julian. We have searched for Minns’ resting place, but without success. The registration of his death just gives his burial place as ‘Norfolk’. A quick Ancestry.com search provided no further detail. James Benjamin Shingles Minns was baptised at St John the Baptist and All Saints in Lakenham and lived in the parish of Lakenham so might he be buried in that church?

LikeLike

Pingback: AF Scott, Architect:conservative or pioneer? | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH