Tags

ely cathedral, favourite buildings, kings college cathedral, kings lynn custom house, norwich cathedral

This was going to be something quite different but in this fifth week of isolation I haven’t been able to take new photographs, the library and record office are closed, so I’m revisiting a few of my favourite buildings to remind us of life outside this bubble.

Possibly my favourite building, the Pantheon in Rome was completed around 126AD by the emperor Hadrian. The generous classical portico leads into a rotunda of staggering beauty. The coffered (sunken) panels reduced the weight of the roof, helping it remain the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome for nearly 2000 years. On our visit, no-one seemed to mind when the rain came in.

Local pride compels me to mention that Norwich had its own Pantheon [1], although with a modest diameter of 74 feet – about half the Pantheon’s – it would have caused proportionately fewer jaws to drop.

The Pantheon in Ranelagh Gardens, just off the St Stephen’s roundabout, became the booking office of Norwich Victoria Station (1913). Courtesy Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

Another stunner is the great dome of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, its diameter only marginally less than that of the Pantheon.

To construct what was, in AD 537, the largest building in the world, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I commissioned a geometer/engineer (Isodore of Miletus) and a mathematician (Anthemius of Tralles). Literally, their task was to square the circle: how to support the circular base of the dome on top of a square base? To make this transition they made innovative use of pendentives – curved triangular segments that allowed the weight of the dome to be spread over the four supporting pillars.

Image courtesy of Buzzie.com

Hagia Sophia at sunset

Another sunset. Approaching Ely from the south, one of the great sights of East Anglia emerges as you crest the brow of a hill and the ‘Ship of the Fens’ rises up.

Ely Cathedral, with the octagonal Lantern at the central crossing. (The taller tower is at the West Front) ©Andrew Sharpe/Geoff Robinson

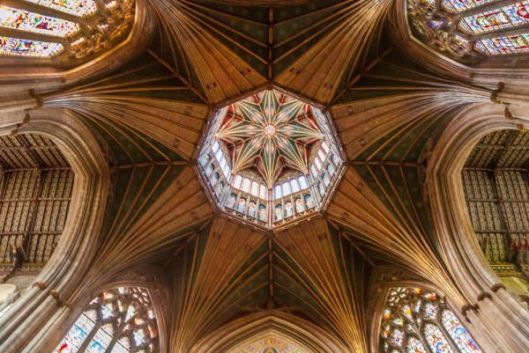

In 1322 the Norman tower at the central crossing collapsed and when it was realised that it was unfeasible to rebuild in stone the King’s Carpenter, William Hurley, was drafted in [2]. The 70 foot span was beyond the capacity of available timbers so, first, he erected an outer wooden octagon, which was painted to resemble the eight stone piers on which it stood. Then, at the centre of this platform, he constructed a lantern around a vertical octagon of eight timbers. Each a prodigious 63 feet long, these beams were obtained from Chicksands Priory in Bedfordshire [3].

The central light well, the lantern, is based on an outer octagon of wood painted to look like stone. Photo credit: David Ross and Britain Express

King’s College Chapel Cambridge – another East Anglian treasure – also gives joy. John Wastell built the beautiful fan-vaulting, giving the chapel the unified appearance of a building completed in a single campaign, but it was started by a Plantagenet (Henry VI) and completed by a Tudor (Henry VIII), with the Wars of the Roses in between (1446-1515).

The chapel has ‘the largest fan vault in the world’. (‘world’ meaning England, for fan vaulting was a native invention). The skin of the stone fans is surprisingly thin and their radiating ribs largely decorative. The main work of supporting the prodigious vault is performed by the transverse arches and tapering external buttresses topped with heavy stone finials to counteract the outward thrust [4]. This external support – no flying buttresses here – creates the illusion of internal lightness, a single space tented with a delicate lacework of something less than stone.

The world’s largest fan vault, King’s College Chapel Cambridge. Creative Commons Licence BY-SA 4.0 by ‘Cc364’

King’s College Chapel. CC BY-SA 3.0 by Dmitry Tonkonog

Even closer to home is the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts on the UEA campus, a bike-ride away. Here there is no illusion, for the superstructure that supports this vast open space is in plain view. Fascinated by the fibres that wrap around plant cells I remember looking up to the SCVA’s tubes and struts, waiting (unproductively, as it happens) for architectural inspiration.

All these buildings offer solutions for enclosing and defining large spaces. This negative space is a fundamental element of architecture that Rachel Whiteread captured in her sculpture ‘House’ (1993). She made a concrete cast of the inside of the house in East London then demolished the skin brick by brick. Jonathan Jones of The Guardian said it was: ‘The solid trace of all the air that a room once contained.’

‘House’ by Rachel Whiteread, 1993. It was decided to demolish the sculpture the day she won the Turner Prize. Photo: Apollo Magazine

The first building to make an impression on me was Cardiff Castle, a Gothic fantasy built on the profits from Welsh steam coal.

The Clock Tower, circled with figures representing the planets

The designer William Burgess restored the castle for the Third Marquess of Bute at the height of the Gothic Revival. On his last visit (1881), Burges worked on the Arab Room with its fabulously intricate ceiling lined with gold leaf. ‘Billy’ Burges built this room in homage to the influence of Moorish art on medieval design. It is considered to be his masterpiece [5].

The Arab Room, Cardiff Castle.

If Rachel Whiteread were to cast the space inside this room it would resemble a Victorian jelly.

Victorian jelly mould. Credit: loveantiques.com

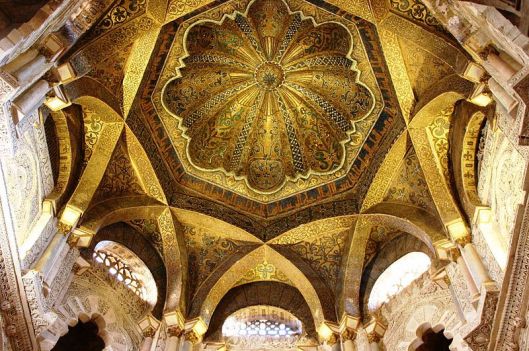

After the Muslims conquered Spain they used the site of a shared Muslim/Christian church to build and extend (C8-C10) the Grand Mosque in Cordoba. When Christian rule was reestablished a Renaissance cathedral was constructed in the middle of the Muslim complex.

The Mihrab Dome, Grand Mosque Cordoba. ©José Luiz Bernardes Ribiero/CC BY-SA 3.0

Perhaps the most inspiring aspect of the mosque is the enormous space punctuated by 856 columns rescued from Roman buildings. The innovative double arches allowed for a greater ceiling height above the relatively short columns.

Of the three buildings in the Piazza dei Miracoli in Pisa, the one on the left fascinates me most.

The Baptistery, Duomo and Leaning Tower, Pisa

The Baptistery was begun by Duotisalvi in 1153 but wasn’t completed for over 200 years, allowing us to see the transition between the rounded Romanesque and the pointed Gothic.

The immense interior is surprisingly plain.

Photo: Tango7174. CC BY-SA 4.0

I last saw Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s masterpiece in 2012, before the disastrous fires of 2014 and 2018.

Glasgow School of Art, 1896. The compositional asymmetry of the Renfrew Street entrance, pictured here in 2012

Photo: Robert Perry/TPSL/Camera Press

Mackintosh’s unique buildings were filtered through a range of influences. For example, the parade of window frames on the north front are reminiscent of Elizabethan ‘prodigy houses’ with their runs of rectlinear windows …

Hardwick House, Derbyshire, 1590-7. Photo: chachu207. Creative Commons licence CC BY-SA 3.0

… while the sheer planes on the east and west elevations echo the high defensive walls of the Scottish Baronial Style [6].

Mackintosh made sketches of this baronial tower-house, Maybole Castle, Ayrshire. ©South Ayrshire Libraries

Mackintosh’s reputation was highest in Austria. When he and his wife Margaret Macdonald were invited to design a room for display at the 8th Secessionist Exhibition of 1900 [7] students paraded them through Vienna on a cart garlanded with flowers, and architect and designer Josef Hoffman– co-founder of the Wiener Werkstätte – described Mackintosh as the leader of the modern movement. This high point contrasted starkly with the latter part of his career when commissions declined and he descended into alcoholism.

The Secession Building designed by Josef Maria Olbrich, Vienna, 1898. Locals refer to the dome as the golden cabbage.

Back in Norfolk, King’s Lynn possesses ‘one of the finest late C17 buildings in provincial England’ [8]. The beautifully proportioned Customs House was commissioned by a local wine merchant, Sir John Turner MP, and designed by local architect, Henry Bell. It was built as a merchants’ exchange at a time when the town was one of the nation’s busiest ports and a hub for trade with Europe.

The Customs House, 1683

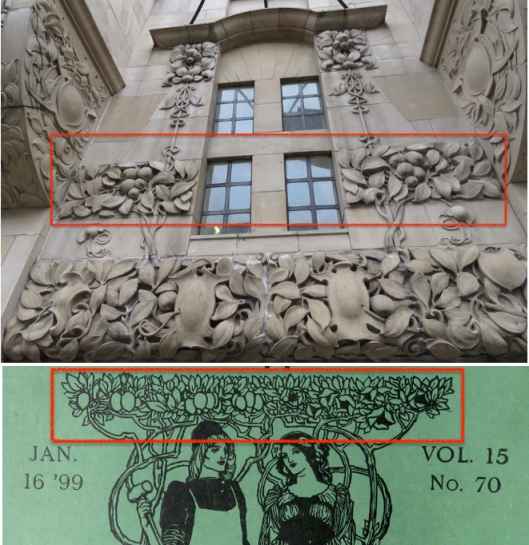

On the opposite side of the county, the ‘only one remarkable building’ of Great Yarmouth, (according to Pevsner and Wilson [9]) is Fastolff’s House. I have written about it previously [10] but it is a neglected gem, one of few buildings in the art nouveau style in this country, and I have been back a few times since.

Fastolff’s House, Great Yarmouth. Designed by RS Cockrill 1908

The building is made of red brick but what transforms it is the facade of white faience. Fastolff’s House is elevated by its applied decoration just as the exterior of Norwich’s Royal Arcade was transformed by WJ Neatby’s Carraraware tiles. Carraraware was developed in Doulton’s Lambeth factory by the head of their architectural department, Neatby, as a weatherproof facade resembling marble. It is not known who made the Yarmouth tiles but the panels of leaves and fruit are in the restrained form of art nouveau – as opposed to the sinuous variety favoured on the Continent – illustrated on the front cover of The Studio around the end of the nineteenth century.

Above, the art nouveau frieze in white faience (red rectangle) echoes, below, the cover design of The Studio from a dozen years earlier.

To lose one spire may be regarded as a misfortune but to lose two looks like carelessness. In 1362, the wooden spire of Norwich Cathedral was blown down in a gale; in 1463, its replacement was struck by lightning. The ferocity of the resulting fire destroyed the wooden roof of the nave and turned the Caen stone pillars pink. Bishop Walter Lyhart – whose rebus of a hart lying on water is dotted around the nave – replaced the roof with a stone vault decorated with short lierne ribs. Completed in 1472, the result was a remarkable 14-bay-long vault designed by Reginald Ely not long after he had finished working on King’s College Chapel. Where ribs intersected he placed 255 stone bosses depicting biblical scenes, from the Creation to Doomsday [11].

The lierne vault of the nave. Beneath it, the massive Norman piers had been turned a pinkish colour by the fire

Norwich Cathedral from the cloisters

©2020 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/tag/norwich-pantheon/

- John Harvey (1988). Cathedrals of England and Wales. Pub: Batsford

- EC Wade and J Heyman (1985). The timber octagon of Ely Cathedral. Proc. Instn. Civ. Engrs, vol 8, part 1: 1421-1436.

- https://www.architectural-review.com/the-romantic-and-pragmatic-history-of-the-fan-vault-has-lessons-for-contemporary-structures/8609423.article

- Rosemary Hannah (2012). The Grand Designer: Third Marquess of Bute. Pub: Birlinn Ltd.

- James Macaulay (1993). Glasgow School of Art: Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Pub: Phaidon Press Ltd.

- Jackie Cooper (ed) (1984). Mackintosh Architecture. Academy Editions, London.

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1999). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 2: North-West and South. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/03/25/art-nouveau-in-great-yarmouth/

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1999). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- Paul Hurst (2013). Norwich Cathedral Nave Bosses. Pub: Medieval Media, Norwich

🙂 thank you

LikeLike

Thank you Daniel. I suppose the lock-down is just as strict in your part of the US?

LikeLike

What lovely escapism – thank you! I’d want to add the Lit and Phil library in Newcastle, but it’s well out of range…

LikeLike

Hello Heather, I didn’t know the Lit and Phil Newcastle but just looked it up. It is magnificent and I feel the itch to travel north.

LikeLike

A wonderful edition, just what was needed in these miserable times. Thank you….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Much appreciated Mike. I wonder for how much longer we’ll be confined to the archives?

LikeLike

What a luxury to be able to travel virtually when we cannot at present do so physically! Thanks for the enjoyable virtual outing. By chance, it was also today that I received a link to a Frank Lloyd Wright Trust video showing the architect’s Oak Park studio. Having viewed that one, I happened on another on YouTube from the same source which was the most astounding fly through of a now demolished Lloyd Wright building- the Larkin Administration Building. I think you would enjoy it if you’ve not seen it.

LikeLike

Hi Pam, I’d love to see the link for the Lloyd Wright building.

LikeLike

Here it is: https://youtu.be/GvCIXNrYVVg

LikeLike

That was an excellent clip on Wright’s Martin House Complex. See more of his troubled life on https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08ywgvm

LikeLike

Thank you for the lovely photos. A friend and I had planned to visit Norwich for a few days next week, inspired partly by your blog. Alas, it will have to wait, but this is some recompense.

LikeLike

Hello Anne, There is quite a lot to see in Norwich although some treasures need ferreting out. Such a pity this virus has prevented your trip. Let me know if you need recommendations when the travel ban is lifted.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved reading this. Wonderful xx

LikeLike

Hi Sophie, So pleased you liked this x

LikeLike

Thanks very much, most enjoyable.

LikeLike

Thank you Roger

LikeLike

Cardiff Castle, was the best!

Reggie showed us around.

LikeLike

Hello Hendrik, Wasn’t Cardiff Castle a treat!

LikeLike

wunderbar!

LikeLike

Danke HB, Sehr Aufmerksam

LikeLike

A post to inspire your readers to pick their favourite buildings – between us all we would pretty well cover the world, though most of mine would be in or around Norwich.

Be you careful in these difficult times

Don Watson

LikeLike

Thank you Don. At the moment I can’t even think of a next post so perhaps I’ll be contacting everyone to send in a photo. Stay safe. Reggie

LikeLike

Absolutely wonderful. Reggie! I spend a lot of my time admiring the wonders of the natural world but, my goodness, these buildings created by man are stunning! Thank you.

LikeLike

As much as I love buildings they pale in comparison to what’s on view through the window. I’m sure you’d agree, Clare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A delightful wander round some fascinating buildings, a good number of which we have had the pleasure of seeing – that mosque in Cordoba the most outlandishly memorable – and some arresting links between structures that one might not have connected until you point out comparative features. I seem to recall the Pantheon had holes in the floor specially designed to get rid of the rain water that didn’t trouble you!

A further dome that you have not told us about is Brunelleschi’s magnificent construction on the top of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. Do you know Ross King’s book “Brunelleschi’s Dome ; The Story of the Great Cathedral in Florence”? It tells the story of the competition the City of Florence set up in 1418 for the construction of a dome to complete the cathedral, and the struggle to achieve it. The structure of the Pantheon is described as a point of reference in the architect’s design. Fascinating

LikeLike

Hello Richard, I had intended to include Brunelleschi’s dome (how could I not) but my own photos, taken before I splashed out on a decent-ish camera, were too poor to enter the original rough list. A mistake. I just dug out my copy of King’s book and now wish I’d included this post-Pantheon wonder. Kind regards, Reggie.

LikeLike