London has its famous residential squares, built to enclose green space and clean air against the awfulness outside. These enclaves mainly arose during the Georgian and Victorian periods and from the outset were part of the designed urban landscape.

Norwich, on the other hand, has very few formal, rectangular spaces. In this second post on Norwich Plains we try to define these irregular spaces by contrasting them with more formal squares.

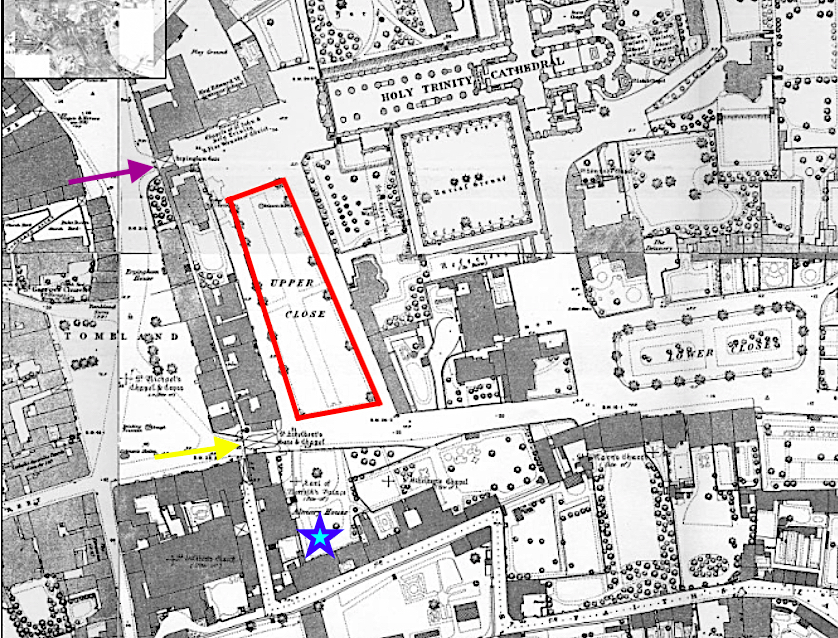

The Anglo-Scandinavian marketplace, Tombland (meaning empty space), and the Norman marketplace that superseded it, are both rectangular but neither of these was called a ‘plain’ for they pre-dated the arrival of the Dutch who gave the name to our open spaces. And although we can point to several isolated Georgian gems there was never sufficient development within the confines of a medieval street plan (if ‘plan’ is the word) to add up to an eighteenth century square. The nearest thing to a London-like square is the Cathedral Close.

Before the word ‘close’ was appropriated by twentieth-century developers for their suburban cul-de-sacs, the name related more specifically to the area around an ecclesiastical building enclosed – cloistered – behind the precinct gates. It may never have been an appropriate name for the more casual, un-green places outside the cathedral walls. Norwich plains are irregular, rather tentative spaces that seem to have arisen where several medieval streets collide. Some plains have been so eroded by tramways, traffic-bearing roads, World War II and general ‘improvement’, that we may wonder whether they existed at all.

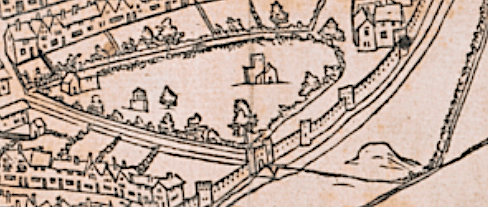

St Catherine’s Plain is one such open space. It was the land surrounding the pre-Conquest church of St Catherine that was given to the nuns at Carrow by King Stephen. Now it is one of Norwich’s lost churches and its demise can be traced to the plague that almost depopulated the parish; by the time of the historian Blomefield (1705-1752) it consisted of just one house [1].

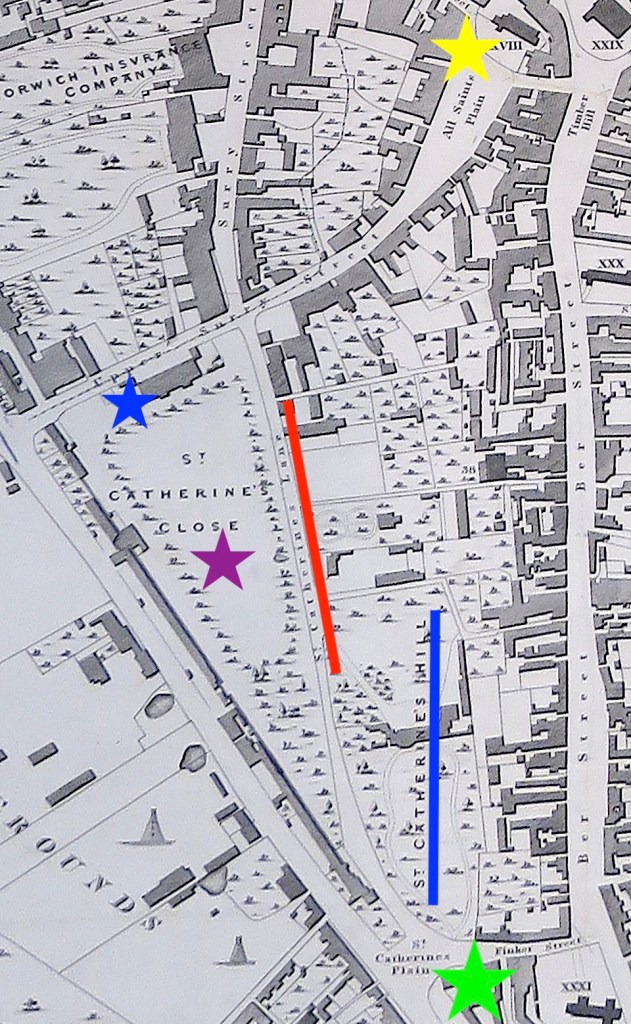

At the southern end of Queen’s Road, between the twentieth century junction with Surrey Street (formerly St Catherine’s Lane) and the following junction with Finkelgate, is a treed area still marked with an older-style cast-iron sign.

Finkelgate connects with the south end of Ber Street, which was once called St. Catherine’s Street [1]. The map below also shows a St Catherine’s Lane and a St Catherine’s Hill, emphasising that the district of St Catherine’s was at one time more extensive than we may now realise.

Walking down Surrey Street to the junction with All Saints’ Green we come to a fine building designed by local architect Thomas Ivory who is responsible for several of the high points of Georgian Norwich. This is his St Catherine’s Close (1780) – a name once given to the place where the parsonage had stood [1] . The Adam-style porch was damaged when the area was bombed during World War II and is a replacement [3].

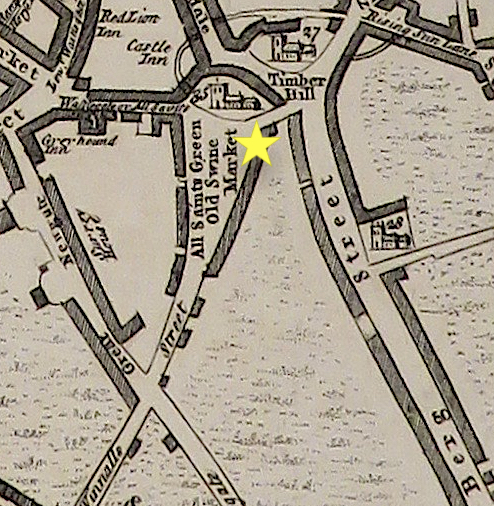

Just east of this house is All Saints Green that, as marked by the yellow star in the 1830 map above, was once known as All Saints Plain. On Samuel King’s map of 1766 this open space is labelled All Saints Green – a name by which it is known today. It appears there was a fluidity in naming places. King’s map also gives the space the alternative name of ‘Old Swine Market’ but by 1806, when Blomefield’s History of Norwich was published, the hog market had moved to the castle ditches.

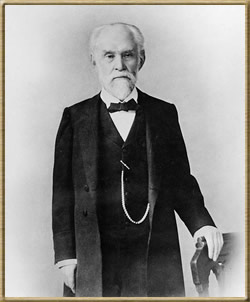

Born 1844 in Ludham, Robert Herne Bond owned a shop in Ber Street and bought adjoining properties that allowed him to extend through to All Saints’ Green [4]. One of these buildings started life as the Thatched Assembly Rooms before being converted to a ballroom then a cinema. Bond converted it back to a ballroom for his staff and it was also used as a restaurant and furnishing hall. The ‘Thatched’ was destroyed by incendiary bombs in 1942. Immediately the war ended, Bond’s son, the architect J Owen Bond, replaced this collection of vernacular buildings with a Streamline Moderne department store. In 1982, Bonds of Norwich was taken over by John Lewis [5].

St Giles’ Plain. The provisional nature of some of the Norwich plains is apparent from Richard Lane’s book The Plains of Norwich. White’s Directory of 1845 does not, he writes, list St Giles’ Plain in the street guide despite several traders giving their address there [2]. Nor could I find it on the 1884 OS map, the Millard & Manning 1830 map, Cole’s 1807 and King’s 1766. This is not to say that the plain didn’t exist but that locals were more ready than mapmakers to use the local name for these open spaces.

The church stands at the intersection of Upper St Giles and St Giles Streets, Cow Hill and Bethel Street, with Willow Lane to the rear. The area outside the church would have looked more tranquil before the 1970s when Cleveland Street joined the plain, bringing traffic off the Grapes Hill roundabout and the Inner Link Road.

Until the Conquest, the settlement’s main axis ran north-south, from Magdalen Street, through Tombland, to King Street. The Normans changed this by developing the ‘French Borough’ westwards from their Castle and Marketplace. Two Norman streets from the market converged at St Giles: Lower Newport (now St Giles Street) and Upper Newport (now Bethel, formerly Bedlam, Street).

The church is situated on a hill, 85 feet above sea level. If you were to stand on top of the magnificent tower you would be 205 feet above the sea; not as tall as the county’s high point, Beeston Bump (344 feet), but still dizzyingly elevated for Norfolk. Two thirds up the tower the single clock-face points down St Giles’ Street to the Guildhall, next to the marketplace. With a diameter of ten feet the dial should have been easy to see although visibility was improved in the mid-C19 by the addition of a six and half feet minute hand.

Facing the south side of the church, across the plain, is Churchman House built in 1727 for Alderman Thomas Churchman and remodelled in 1751 by his son Sir Thomas. According to Pevsner &Wilson this is ‘the very best Georgian house in Norwich’ [3].

For two years (1875-7), Churchman House was the first home of the Norwich School for Girls before it moved to the Assembly House and then to its present location on Newmarket Road in 1933 [2]. After the girls moved out in 1877, Churchman House was bought by Dr Peter Eade, sheriff and three times mayor. Dr Eade was an eminent citizen, being Chief Physician at the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital, on St Stephen’s Road. He was also first President of the Norwich Medico-Chirurgical Society at a time when meetings would be held on the night of a full moon to help members return home safely.

Dr Eade was also embroiled in the affair of Sir Thomas Browne’s skull, that I recently wrote about [6]. Physician and philosopher Thomas Browne, the city’s most famous citizen of the seventeenth century, was buried in the chancel of St Peter Mancroft. In 1840 his skull was stolen when his coffin was broken open during the burial of the vicar’s wife. After some years the skull was bequeathed to the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital Museum where, despite numerous requests for its return, it stayed until 1922. Peter Eade ‘must have been one of the leading figures behind the hospital’s refusal to return the skull’ [7]. At the time, skulls of the famous were used for phrenology, the pseudo-scientific name for ‘reading the bumps’ – the dubious procedure for deducing personal characteristics from the shape of the cranium. Yet while Eade the Physician fought against the restoration of the skull, Eade the Mayor championed the commission for Browne’s statue, which was installed in the Haymarket in 1905 [7].

St Mary’s Plain feels more of an open space than others in Norwich-over-the-Water, possibly because of the borrowed elbow room provided by the large churchyard.

The plain takes its name from St Mary-at-Coslany, Coslany (or island with reeds) being one of the four original Anglo-Saxon settlements on which the city is based. On the belfry, the double openings with the recessed shaft reveal the church’s Anglo-Saxon origins. It is probably the oldest in Norwich [3].

Until the late C19 the area consisted of ‘noxious courts and alleys’ [2] but all this was to change dramatically in the following century. Norwich-over-the-Water housed many light-industrial factories and was bombed several times during the Baedeker Raids. In 1942 the church was badly damaged by incendiaries.

Above, just visible to the left, is St Mary’s Baptist Chapel. It dates from 1951 although various versions had stood on this site since 1745. Below, is the chapel on the 12th of September 1939.

War had been declared against Germany on the 3rd September 1939. A week later, fire swept through the Baptist church but this was not caused by enemy action – a hint of the damage can be seen on the roof. Rebuilt to the original design, the church was opened again a year later but in June 1942 was completely gutted, this time as a result of the Baedeker bombing campaign. The church we see today was opened in July 1951 (see [8] for the detailed history of this area and of wartime bomb damage).

The Baedeker raids of 1942 also claimed medieval Pykerell’s House, named after an early C16 Sheriff and three-times mayor. Extensively restored, it is one of only six thatched houses left in Norwich. Surprisingly, I can find no reports that its conjoined but unthatched neighbour – Zoar Strict and Particular Chapel – suffered any damage in the blaze. In evading the Luftwaffe’s incendiary bombs the church was echoing its biblical namesake, Zoar, one of the five cities of the plain (the Dead Sea Plain) to escape the fire and brimstone that destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah.

It is intriguing that Zoar, a small Baptist chapel, should be sited so close to the large, general Baptist Chapel further along the plain. This break-away branch of the Baptist faith is ‘strict and particular’ in allowing only those baptised by immersion to receive communion.

The shape of the plain as we saw it on King’s map of 1766 was further changed in the 1920s. Then, old slum dwellings were demolished to make way for St Mary’s Works, home to Sexton, Son and Everard, one of the city’s large shoe-making factories. But it, too, was extensively damaged in 1942 by the summer bombing campaign. The building was restored but the business closed in 1976 and now it awaits redevelopment.

Postscript

In researching the city’s open spaces I came across an article that gave insight into the extent to which the cathedral’s brethren fulfilled their moral obligation to feed the poor [9].

Almary Green is not named for the Virgin Mary but because of its proximity to the Almonry. The Almoner’s House and Almonry Green are situated in the south-west corner of The Close conveniently near the paupers soliciting alms at St Ethelbert’s Gate. Here, the almoner had his own granary, distinct from the priory’s Great Granary. This separation ensured that the needy were fed mainly rye or ‘horse’ bread to accompany their soup or pottage based on pulses while wheat from the other store was used to make the white bread eaten by the brethren. From the accounts, the monks appeared to have eaten and drunk in ‘truly heroic quantities’. Bread and ale comprised about half their diet while fish and meat (but little dairy and no fruit and vegetables) made up the other half. Modern nutritional guidelines suggest the paupers had the better deal.

In 1422, on Maundy Thursday, sufficient supplies were distributed to feed 5,688 poor. And on the anniversary of the death of the founder, Herbert de Losinga, around 10% of the annual allocation of rye, peas and barley was doled out in one day. It is not clear how the remainder was distributed throughout the rest of the year. In 1310-11, 33,000 loaves, 28,500 portions of pottage and 216,000 gallons of weak ale were given to the poor. If no food was distributed outside the charity season then the soup kitchen could have catered for around 1350 persons, possibly served by the monks. If, however, food was provided throughout the year then the almoner could have fed around 500 paupers a day [9]. Despite the fact that Norwich was a relatively wealthy city it is clear that a large part of the population required social care and it was the church that provided it before the Elizabethan Poor Laws.

Sources

- https://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-hist-norfolk/vol4/pp120-145

- Richard Lane (1999). The Plains of Norwich. Pub: The Larks Press, Dereham.

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk I: Norwich and the North-East. Yale University Press.

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/agr.htm#Allsg

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2020/08/15/twentieth-century-norwich-buildings/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2020/07/15/thomas-brownes-world/

- http://www.racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp?action=getsurvey&id=307

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/stj.htm#Stmap

- Philip Slavin (2012). Bread and Ale for the Brethren. In, Studies in Regional and Local History vol 11. Pub: University of Hertfordshire. https://www.academia.edu/3346435/Bread_and_Ale_for_the_Brethren_The_Provisioning_of_Norwich_Cathedral_Priory_1260_1536

Thanks

The main source for this post has been Richard Wilson’s excellent book on Norwich Plains. As ever, I am grateful to Jonathan Plunkett for generously allowing access to his father’s collection of C20 photographs of Norwich.

Another absorbing post, thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you for the kind words. Reggie

LikeLike

Always a fascinating read. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you Martin. You will have noticed the Dutch influence, Reggie

LikeLike

Two splendid posts. I had not thought of several of these open spaces as being ‘plains’ and do not remember hearing some of them so spoken of. Always something to learn. Thank you

Don Watson

LikeLike

Hi Don, I’m following Richard Lane’s book on Norwich Plains. He notes that although some plains don’t appear as such on a map, residents give the plain as their address in White’s Gazetteer. I posted that All Saints’ Plain is on one map but not another so there may have been a reluctance to use the term in formal circumstances. Most plains occur where several streets meet and my suspicion is that if locals lived on these junctions they gave the colloquial name as their address since that was the most distinctive feature. It’s interesting to hear, though, that a genuine Norvicensian hasn’t heard of some being referred to as a plain. I’m interested to know which ones. Next month I’ll be finishing with St Benedict’s Plain, St George’s, St Margaret’s, St Paul’s, St Stephen’s and Theatre Plain. Look forward to your reply. Reggie

LikeLike

Maddermarket Plain, and St Giles Plain were never so referred to in my childhood and as in the 1940’s our buses (the 86 and 87) started from a yard now incorporated into into the St Andrews car park I must have passed by it fromDove St (my mother regularly shopped in Chamberlains) frequently, particularly from 1946 when I started at Norwich School. It is interesting that one of the names for All Saints Green was All Saints Plain – perhaps it should have reverted to that when it was closed to through traffic. I look forward to the next episode.

Don Watson

LikeLike

Thank you for this Don. I am increasingly convinced that the naming of plains, as occasional open spaces, was a vernacular thing that didn’t always gain formal status.

LikeLike

A well researched and interesting post, as always. Thank you very much, Reggie.

LikeLike

Thank you Clare. Haven’t quite finished with the Norwich plains but it may be a while before the final post on that topic appears.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fascinating read. Many thanks.

LikeLike

Much appreciated, Jeremy.

LikeLike

Pingback: Vanishing Plains | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Plans for a Fine City | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH