In these covid times I cycle. Along the celestial Unthank Road to the junction with Newmarket Road, down the hill to Eaton and out to open countryside. Before the crossing is a house with two intriguing names carved in stone on the gate pillars. The first is badly spalled and its few remaining letters … CRO … would be unknowable except for a modern house-plate, Hillcroft. Although a few of its letters are obscured the other sign can only be for the Royal Norfolk Nurseries.

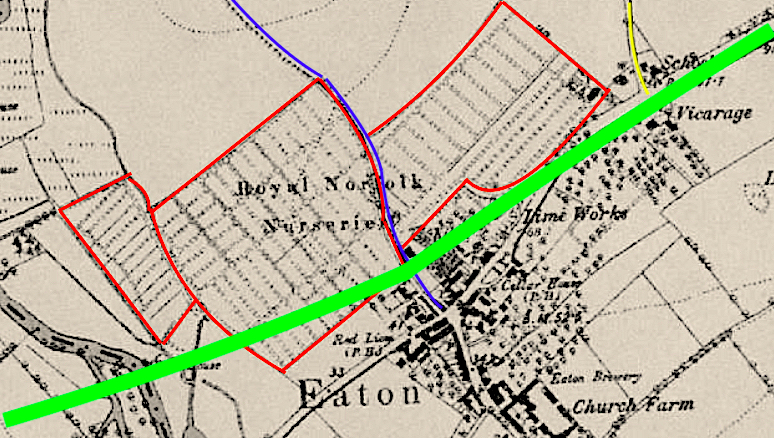

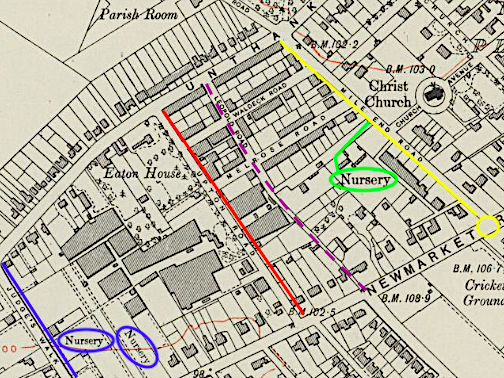

I was curious to look into this because for several years I’d wondered about the clear, unbuilt-upon spaces on the early maps marked ‘nursery ground’ or ‘garden ground’. The OS map of 1879-86 shows that the Royal Norfolk Nurseries occupied sites from the junction with Unthank Road (yellow) down the hill to Bluebell Road (blue) and a larger area between Bluebell Road and the river, now in the shadow of the A11 Eaton flyover/bypass (green).

Much of the land, from the Unthank’s estate east of Mount Pleasant in Norwich [1] down to Eaton, was owned by the Dean and Chapter of Norwich Cathedral; this applied to the village itself with the notable exception of a few oases, including the 12 and 17 acre plots owned by the Corporation of Eaton.

The 1838 tithe map and accompanying apportionment record (1839) gives the name of landowners liable to pay church tithes and, within the two outlined areas, William Creasey Ewing (1787-1862) owned most of the individual numbered plots.

The son of William Creasey Ewing, John William Ewing (1815-1868), evidently inherited the land from his father and is listed as Nurseryman, Florist, Lime burner (and there is a lime pit on the site) and Seedsman [2].

Below is The Old House, Church Lane, Eaton (formerly known as Shrublands) where William Creasey Ewing lived. The National Census records his son John William living there in 1851 [2].

Prior to this census return, John William Ewing lived in Shepherd’s House near Mackie’s, the city’s long-established and foremost nursery, founded in the 1700s on Ipswich Road [1]. We’ll come to Mackie’s shortly.

Between 1833 and 1840, John William Ewing and Frederick Mackie entered into a partnership, forming Mackie and Ewing’s Nurseries, but in 1845 the partnership was dissolved. A newspaper advertisement to this effect places JW Ewing in Ewing’s Nursery at Eaton, indicating that JW Ewing was managing the nursery when he was 30, if not before.

A year later, (incidentally the year his son and successor was born) an invoice from JW Ewing, Nurseryman and Seedsman, shows that the Eaton Nursery was selling ‘Forest & Fruit Trees, Flowering Shrubs etc’ and, in smaller script, ‘Garden & Agricultural Seeds, Dutch Bulbs, Russian Mats (anyone?)*, Mushroom spawn etc.’ *(A reader, Lyn, provided the answer. Russian Mats, exported via the port of Archangel, were closely woven from the leaves of aquatic plants and used to protect fruit trees and young plants etc).

When he died, Ewing’s Royal Norfolk Nurseries were inherited by his son, John Edward Ewing (1846-1933), but when John left Norwich in 1893/4 the business at Eaton was lost.

In his History of the Parish of Eaton (1917), Walter Rye wrote that ‘the chief trade of the village is now growing fruit trees and roses for the market’ [3]. He went on to say that other well known Eaton nurseries are the three rose nurseries of C Morse, E Morse and RG Morse and the ‘old-established nursery of Mr Hussey in the Mile End Road.’

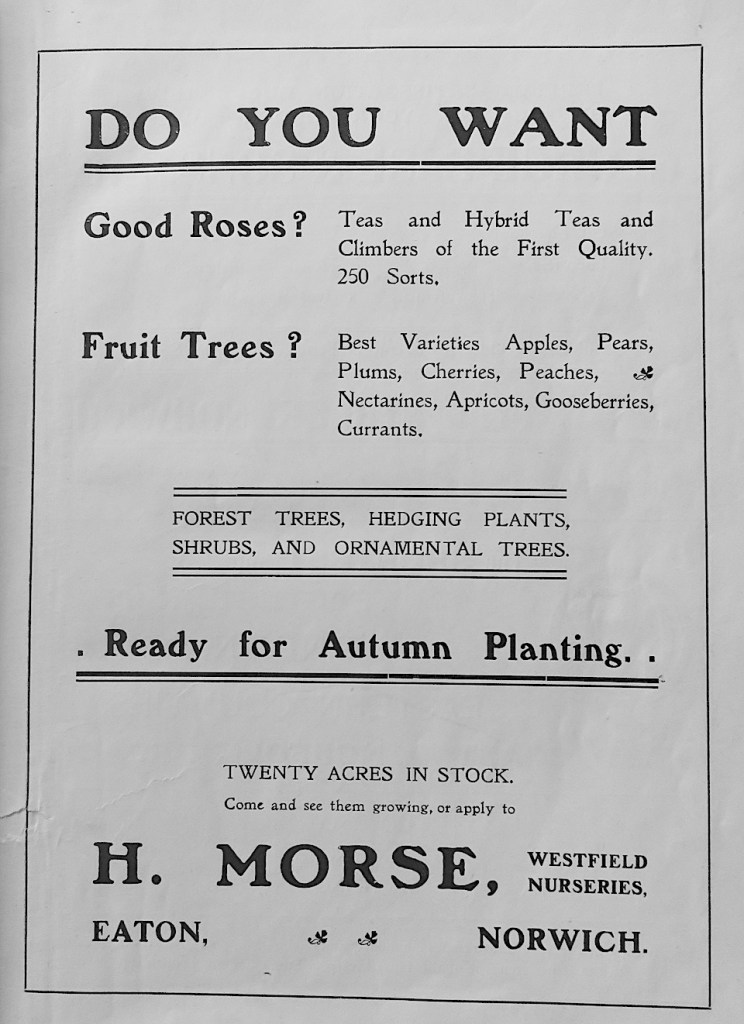

Ernest Morse appears in this 1910 book of local worthies and businessmen [4] advertising himself as a grower of fruit, cucumbers and grapes. His older brother Henry took out a full page advert announcing his 20 acres of rose bushes and fruit trees in the Westfield Nurseries, Eaton.

John Ewing’s partnership with Mackie’s was dissolved in 1845, leaving Mackie’s to stand alone as the city’s predominant nurserymen.

The industrial scale of Mackie’s operations made it one of the largest provincial nurseries [5, 6]. Bryant’s 1826 map (above) shows Mackie’s 100 acre site was situated around the crossroads where present-day Daniels Road intersects Ipswich Road but the business can be traced back to John Baldrey’s nursery in the city where, around 1750, he was selling plants and trees on a wholesale basis. In 1759, this was taken over by the Aram family – who were selling ‘Scotch firs’ at ten shillings per thousand – and in 1777 John Mackie joined the business. This was around the time the nursery moved to what, in its final days, was to be known as ‘the Daniels Road’ site.

Parson Woodforde knew Mackie:

“Mackay, Gardener at Norwich, called here (the parsonage at Weston Longville) this Even’, and he walked over my garden with me and then went away. He told me how to preserve my Fruit Trees etc. from being inj’ured for the future by the ants, which was to wash them well with soap sudds after our general washing, especially in the Winter.”(from Parson Woodforde’s diary, July 13 1781).

As Louise Crawley describes in her essay on the Norwich Nurserymen, Mackie’s site was so extensive that clients recorded being driven around it by carriage [6]. Mackie’s was to remain in the family for four generations until it was sold in 1859 when they emigrated to America [5, 6].

Fifty years after this map was made the Ordnance Survey recorded that a portion of Mackie’s Nursery at Lakenham had become the Townclose Nurseries. Later still, this was to be purchased by the Daniels brothers.

Daniels was sold to Notcutts in 1976. By superimposing modern roads on the nineteenth century map we can see how construction of the Daniels Road portion of the ring road in the 1930s (circled in red) bisected the Townclose Nurseries, with the ‘Notcutts’ portion on the south-western/left side.

In 1849 Mackie’s ventured beyond the parish of Eaton when they bought The Bracondale Horticultural Establishment, situated in the crook between City Road and Bracondale. Patrons were welcome to visit the nurseries but orders could be placed at Mackie’s warehouses in Exchange Street where customers could also buy seeds and catalogues.

A print in JJ Colman’s album shows Read’s Bracondale windmill (1825-1900). Photographed from the Bracondale Horticultural Establishment it shows a plot with supporting canes and, in the background, heated glasshouses.

The trade card, below, from around 1830, shows the extent of the glasshouses that Mackie inherited when he bought the Bracondale Horticultural Establishment from JF Roe. Their exotic produce appears in the foreground: grapes, melons, ‘forced fruits’ and – most romantically foreign – the pineapple.

As a young boy, before I knew words like ‘epicurean’, I visited Cardiff Castle and was shown a table with a hole through which a pot-grown vine would be placed for the Marquess of Bute’s family to snip their own grapes. Unless, of course, they are peeled for you, grapes are pretty low down on the totem pole of self-indulgence since they can be readily grown outdoors or in an unheated glasshouse. But in previous times the seriously rich would grow pineapples in hothouses, as much a show of wealth as a token of their hospitality. Indeed, from the sixteenth century onwards there was something of a pineapple mania. Large country estates with heated glasshouses and staff could afford to grow their own tender fruit and plants. Norfolk estates may have produced pineapples, but this would have been beyond the dreams of the villa-owning classes in the Norwich suburbs [5] who looked instead to commercial nurseries like Mackie’s to provide their hothouse products.

On a national basis, however, Mackie’s reputation rested not with fancy fruit and bedding plants but with the quantity of their arboricultural stock. In 1849 they auctioned ‘one million forest trees’ and in 1796 they were able to send 60,000 trees to an estate in West Wales. The journey from Norwich to Pembrokeshire required the trees to be carted to London then onwards by sea: such transportational hurdles would be largely overcome by the arrival of the railways. When trains came to Norwich in the 1840s, Mackie’s were able to offer ‘instant arboretums’ of 650 varieties of trees and shrubs for £35 [5].

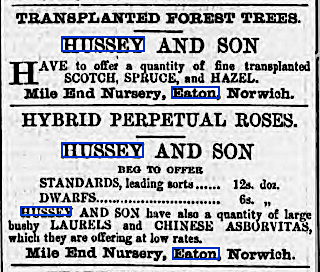

In his History of the Parish of Eaton (1917) [3], Walter Rye mentions ‘the old-established nursery of Hussey in the Mile End Road.’ An advertisement from 1869 shows that their Mile End Nursery was, like its larger competitor (Mackie’s) on the other side of the Newmarket Road, offering trees and roses.

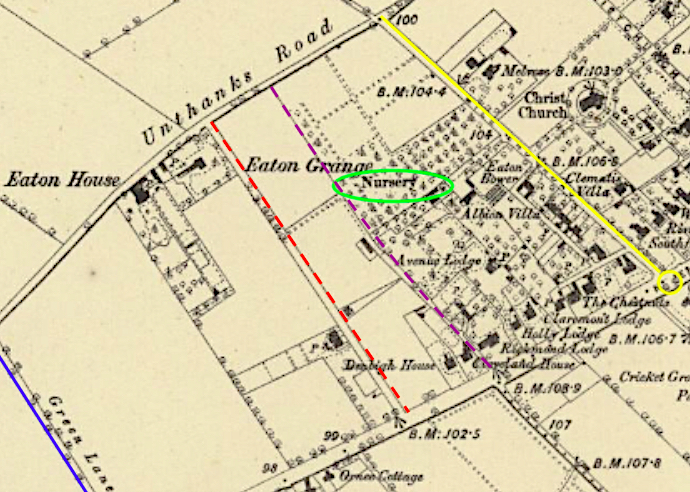

In 1885, Husseys occupied much of the area between Unthank(s) Road and Newmarket Road, stretching from the Mile End Road (now ring road) to what would become Leopold Road.

By the time of the 1908 Ordnance Survey (though for clarity I show the 1919 map), Hussey’s had another nursery on its doorstep. What had been open ground to the west/left of Upton Road was now occupied by large structures, longer and wider than the terraced roads that had arisen on Hussey’s land.

In the period between the 1885 and the 1908 Ordnance Surveys, EO Adcock had bought the open land to the west of Upton Road and established a nursery producing plants on an enormous scale. Meanwhile, Hussey’s had contracted, a good part having been sold to build Waldeck, Melrose and Leopold Roads. The remainder was still accessible through the entrance off Mile End Road [7].

Edward O. Adcock started as an amateur cucumber grower with eight glasshouses at a time when a dozen cucumbers commanded £1 [7]. To put this in perspective, in 1900 the pound was worth over a hundred times what it is today (although cucumbers are still 95% water).

In an article eulogising Adcock as one of the ‘Men Who Have Made Norwich’ [7], he is said to have had 125 glasshouses, each 120 feet long, totalling a quarter of a million square feet of glass. As well as cucumbers, Adcock grew chrysanthemums and, by selling 300,000 per annum, he was claimed to be the largest grower in the world.

Twenty two acres were devoted to asparagus. Adcock also grew tomatoes in prodigious quantities: in one day his staff picked and packed over two tons of tomatoes to be dispatched by rail [7].

What fascinates is the sheer scale at which fruit, vegetables and flowers were produced in just one small part of Norwich. Adcock’s were operating well into the steam age and were evidently able to supply their produce around the country in reasonable time. On a less industrial scale, maps of nineteenth century Norwich give tantalising hints of allotments and other small nurseries such as: Cork’s nursery ground; Allen’s Nursery around Sigismund and Trafford roads in Lakenham; the nursery ground off Dereham Road; the Victoria Nursery in Peafields, Lakenham; George Lindley’s nursery at Catton. Long before refrigerated transport and the concept of food miles it was this web of horticultural enterprises that, together with our farms and markets, fed Norwich.

If you liked this article you may like the Norfolk Gardens Trust Magazine. Membership of the NGT is only £10 per annum, £15 joint, and for this you will receive two copies of the magazine annually, invitations to visit gardens not always open to the public, and talks by leading figures on gardens and the history of designed landscape. Click the link to see more: https://www.norfolkgt.org.uk/membership/

©Reggie Unthank 2021

Sources

- https://familypedia.wikia.org/wiki/William_Creasey_Ewing_(1787-1862)

- https://familypedia.wikia.org/wiki/John_William_Ewing_(1815-1868)?fbclid=IwAR0nbF2FtFgtEnV6xWSr66pwNxH0IxCt3TjeGZ09a16Apjz8B4DvjQ24DHo

- Walter Rye (1917). History of the Parish of Eaton in the City of Norwich . Online at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b756725&view=1up&seq=7&q1=fruit

- ‘Citizens of No Mean City’ (1910). Pub: Jarrolds, Norwich.

- Louise Crawley (2020a). The Growth of Provincial Nurseries: the Norwich Nurserymen c.1750–1860. Garden History v48 pp 119-134.

- Louise Crawley (2020b). The Norwich Nurserymen . In, The Norfolk Gardens Trust Magazine No 29. This article appears in the magazine, available online at: https://www.norfolkgt.org.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/NGT-magazine-Spring-2020.pdf

- Edward and Wilfred E Burgess (1904). Men Who Have Made Norwich’. Reprinted in 2014 by The Norfolk Industrial Archaeology Society in 2014. A truly fascinating read – visit http://www.norfolkia.org.uk/publications.html

Thanks My main source for information on Mackie’s was Louise Crawley, postgraduate researcher at UEA, and I am grateful for her generosity in sharing her researches into ‘The Norwich Nurserymen’. Local historian Vivien Humber kindly shared information on nurseries in the parish of Eaton. I am also grateful to Pamela Clark, Susan Brown, Sally Bate, Tom Williamson and Beverley Woolner. Thanks to the Norfolk Industrial Archaeology Society for allowing me to reproduce the Adcocks photographs, to Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk, and to the George Plunkett archive.

Thanks for this wonderful article. You ask about Russian Mats. I think they were used as plant protection, probably on cold frames. I believe they did originate in Russia.

LikeLike

Another reader confirms your definition of Russian mats, Pamela. It seems that dried sedge and leaves from aquatic plants were made into close-woven mats and used to protect trees from frosts, used in glasshouses (much like lime-washing the glass in summer), protecting tender plants etc etc. The mats were exported via Archangel, hence sometimes known as Archangel mats.

LikeLike

Thomas Fuller – Norwich ‘either a City in an Orchard, or an Orchard in a City, so equally are Houses and Trees blended in it’

LikeLike

Hello Huw. I have already replied to you on Twitter but – to repeat the thought – I wish I’d used Fuller’s quote in this context. Maps of Norwich have always shown just how much open space there was within, as well as surrounding, the city. Our parks and trees are a reminder of this. Kind regards, Reggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely to read what a horticultural centre Norwich was. Thank you

LikeLike

Hi Sue, Seems that the city was always a centre for horticulture, parks and gardens and plant science, from the time of our Dutch incomers onwards. R.

LikeLike

Fascinating stuff! The site of Morse’s nursery on Bluebell Road has a Dawn Redwood

(Metasequoia) which is thought to have grown from the first seed brought to Britain from the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard University in 1948. The tree was discovered in 1944 in China and previously thought to be extinct. It is now quite a popular ornamental tree.

LikeLike

Thank you for that George. I shall make detour on my bike ride in order to see the tree. Reggie

LikeLike

As you go along Blubell Road from the flyover it is one of the first houses on the left (formerly the nursery managers house). Tree is in garden, left side of house as viewed from Road (no leaves of course at the moment, as it’s a deciduous conifer). [See Tom Green’s note, above, on the siting of this tree in comment from 17th Jan]

LikeLike

Until we moved in 2011 andd the garden was neglected and trashed, we spent 30 odd years at Westfield 11 Bluebell Rd, the Morse House, with the daughters initials carved in the brickwork by the backdoor. We have Morse family photos from 1930 (when the house was built) etc etc We tended the garden, maintaining it in the spirit of the family, What a sad day when developers began to bury the last of the Morse Heritage. That’s progress? Make contact for copies of our archive.

Tom and Stephanie Green

LikeLike

Thank you Tom and Stephanie. I will be in touch.

LikeLike

Just to Confirm Dawn Redwood location. It is in the garden of number eleven the second house on left-hand side {of Bluebell Road} after the flyover. It was the Morse family house built in 1930. The next two red brick houses were staff houses during the twentieth century. Although we made sure that Tree Protection Orders were placed on many of the trees in the area a significant number have recently been felled by owners and developers.

LikeLike

Thank you for the clarification Tom

LikeLike

A good exposition of the Eaton nurserymen – it is indeed salutary to see just how many large and small nurserymen and market gardeners were established in just a portion of the country outside the city walls. I remember Daniels’ shop in Bedford Street because, being at school in Norwich, it became my job to buy the vegetable seeds there – much better quality than Bees Seeds from Woolworths (so I was told). That establishment was one of a few which still in the 1950’s had only a beaten earth floor.

Do you keep up the good work, bor

Don Watson

LikeLike

Don, you always have such fascinating information about Norwich as it was. Is the shop still there in Bedford Street?

LikeLike

As a building it probably is. I remember it as being somewhere opposite Little London Street but exactly where I can’t say now – it’s a long time ago

Don Watson

LikeLike

Don Watson is quite right, the shop stood about opposite Little London Street and became The Granary when Daniels left. The facade is still the same as it was. My father, A.E. (Jim) Malt was the firm’s manager and later managing director, having spent his working life in the horticultural and agricultural seed trades, beginning as an apprentice to Daniels. The shop was then in the Royal Arcade – I still have the keys!

I have photos of the Bedford St premises and the Daniels Rd nursery opening if they would be of interest. A large collection of the firm’s catalogues, beautifully printed by colour lithography by Fletchers of Norwich, was deposited at the Norfolk Rural Life Museum, Gressenhall, when the firm was sold.

LikeLike

Thank you for fixing the site of Daniel’s shop, Dick. Fascinating to hear that The Granary (now Jarrolds modern furniture store) was previously home to the seed trade. I would very much like to see those photographs, please.

LikeLike

That’s really interesting. Our garden backs onto where Adcock’s nursery was. We found an interesting water (?) cistern / tank underneath our garden. I wonder if it is connected to the nursery?

LikeLike

Hello Mel, In ‘The Men Who Have Made Norwich’ it is mentioned in the chapter on EO Adcock that “water is pumped by a powerful engine from a deep well into large tanks, several of which hold some 2,000 gallons each.” Could your tank be one of these?

LikeLike

Really interesting – thank you! I was brought up in Cringleford (my father was the doctor there and, I think, counted Colonel Unthank amongst his patients). My parents moved to Poplar Avenue after a period in Bergh Apton, and were pleased to be living right next to where Morse’s Nurseries used to be – a place I can remember visiting as a child.

LikeLike

Colonel John Salusbury Unthank was the last (of three) Colonel Unthank(s) to live at Intwood Hall. He died in 1959 so it is quite possible that he would have visited the nearest surgery at Cringleford. I had to check to confirm that Poplar Avenue is on the high ground above the Morses former land. It is hard to believe that this land, down to the river, was once the site of thriving horticultural industry, now transformed by the flyover and housing development along Bluebell Road. It is gratifying to know that the connection with the city’s extensive nurseries lives on.

LikeLike

The sale of Daniels Nursery to Notcutts in 1976 was preceded by a local political outcry. The freehold of the nursery was owned by the trustees of the Norwich Town Close Estate Charity. When the City Council expressed an interest in acquiring parts of Daniels Nursery which Notcutts did not wish to purchase, the trustees of the Charity sought to impose a restrictive covenant limiting the housing to be built on that land to no more than 4 per acre. In the event the council acquired the land and proceeded to build a significant amount of social housing (Plantsman Close etc) in what was a marginal constituency.

LikeLike

Thank you, Matthew, for the insight into the politics underlying the sale of this part of the Town Close Estate.

LikeLike

So interesting. Thank you, Reggie. I’ve heard gardeners on Upton Road remark on how much broken glass they keep digging up. Must be the remains of all those glass houses!

LikeLike

Hi Sarah, The photographs show an immense amount of glass in that area. A correspondent mentioned a modern parallel – the enormous tomato green houses being erected on the Crown Point Estate at Kirby Bedon. These could provide 10% of the UK’s tomatoes and the project is based on renewable energy. The late Victorian glasshouses on the Upton Road site seem all the more impressive by comparison.

LikeLike

My father, Dr RK Bryce told me that a bomb or bombs fell on the greenhouses in Eaton and scattered glass far and wide I was born on Ipswich Road and now live on Newmarket Road. when we first moved here in 1978, I picked up box loads of broken glass, and still find the occasional bit

LikeLike

My copy of the Norwich bomb map is, I’m afraid, low resolution (it is a very big map). I think I can see, however, that bombs did fall in the area where the plant nurseries were in Eaton. I have heard other reports of residents picking up lots of glass in their gardens and the bomb(s) would explain it. Thank you, Reggie.

LikeLike

Pingback: A postscript on Eaton Nurseries | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Brilliant article,as usual.In about 1950 I seem to recall anentry to glass houses half way along Judges Walk,but its a very dim memory,so I could be wrong!

LikeLike

Hello David, On the 1951 OS map, a nursery is still present off the east side of Judge’s Walk so you may well be right. All best, Reggie

LikeLike

Pingback: AF Scott, Architect:conservative or pioneer? | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Approximately 100 years after the death of William Creasey Ewing, my dad took me into our local butchers. It was opposite the Red Lion on Eaton street/Newmarket road. I think they pulled it down some time ago to make a delivery entrance for what is now Waitrose. The butchers was called Creasey’s. Just coincidence ?

LikeLike

It does seem likely doesn’t it? A deeper search is needed than my quick effort that only turned up Creaseys butchers of Woodbridge.

LikeLike

so pleased to read your article…having the surname of Allen and being the fourth generation to live on the site of our old family nursery at Felmingham. I was lead to believe my great grandfather William,and his brothers had a nursery at Lakenham and Mount Pleasant giving rise to Allen’s Lane? Family tree shows family members being born at Lakenham, so this adds to the ‘tree’.Any other info would be greatly received!

LikeLike

Hello Gail, You can find more information about the Allen who owned the Nursery Tavern/Trafford Arms on traffordarms.co.uk/history, and norfolkpubs.co.uk (look for Norwich Pubs then Trafford Arms). This is presumably the Lakenham branch of your tree. I’m afraid I could find nothing about Allen’s Lane in Sprowston. Let me know of nurseries in Sprowston if you find them.

LikeLike

I lived in Hillcroft as a child from 1970-74 (it was my grandparents house from about 1960-74) and was always fascinated by that gatepost with The Royal Norfolk Nursery’s on it. Thanks for all the information.

LikeLike

Thanks for the contact Nick. I’m delighted to meet a member of the Daniels family.

LikeLike

This is such a brilliant page/set of information. We moved onto Bluebell Road last year and I’m desperately trying to find out some information about what our property used to be; easier said than done. We are 1-3 Bluebell Road, directly before the flyover. From what I can tell, the property used to be farm workers cottages for the nurseries (possibly Hall Farm Cottages 1 and 2) but I can’t find enough to be sure! Any local knowledge?

LikeLike

Thank you for the kind words Joseph. I’ll contact you separately about the farm cottages.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Sons of Flora | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH