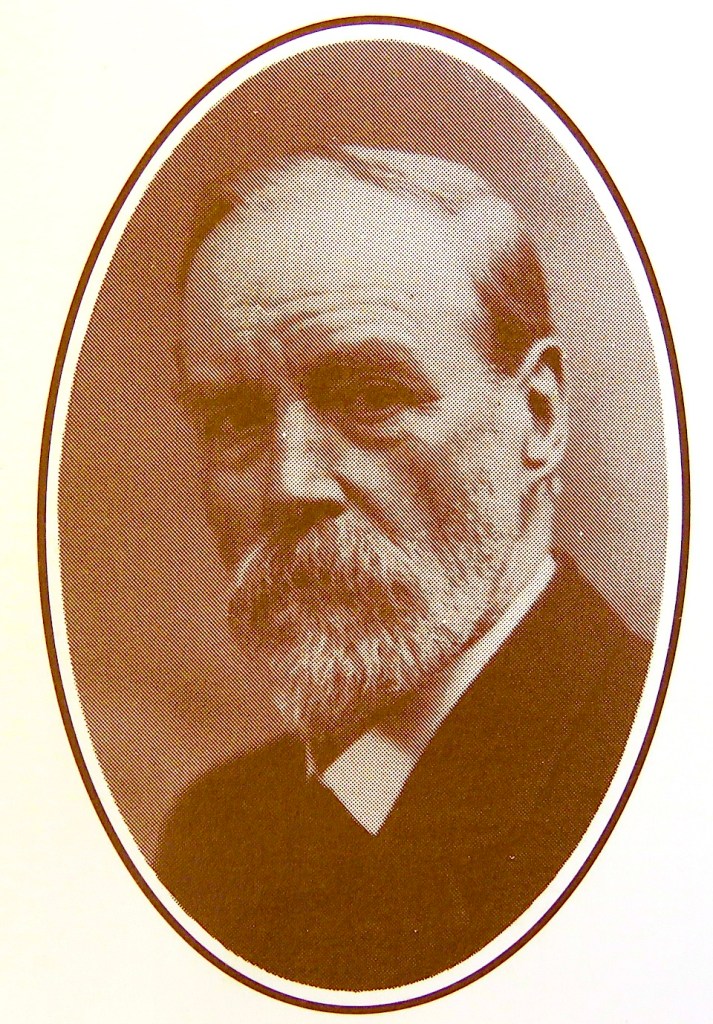

In the previous post on Norwich department stores I mentioned the architectural practice of Augustus Frederic Scott three times, more even than local hero George Skipper – and Edward Boardman not at all. Who was this architect whose factory building was described by Pevsner as the most interesting in Norwich and of European importance? [1] He was also big in Cromer where my interest had been piqued by two turreted houses that could possibly be by AF Scott.

Scott was born in 1854 in the south Norfolk village of Rockland St Peter. His father, Jonathan Scott, was a Primitive Methodist preacher. The Primitive Methodists – sometimes called ‘Ranters’ because of their enthusiastic style of preaching – proposed a return to the original form of Methodism practiced by John Wesley.

AF Scott was educated at the ‘old Commercial School’ in Norwich [3]. This seems to have been the King Edward VI Middle School, established in St George’s Street in 1862 as an offshoot to the King Edward VI School (Norwich School) in the cathedral precinct. The aim of the Commercial School was to prepare boys for industry and trade, in contrast to the more classical education offered by the main school. The school was sited in the west range of the Blackfriars’ cloisters; it had 200 pupils, paying a tuition fee of four guineas per annum [4]. Now it is part of Norwich University of the Arts.

This complex of buildings comes down to us as the most complete medieval friary in England [6]. Its survival can be attributed to the fact that in 1540, during the Dissolution, Mayor Augustine Steward spent £80 to buy the site for the city. Apart from being requisitioned as stables during Kett’s Rebellion the two halls have been in municipal use ever since. St Andrews Hall was the nave of the Dominican priory and its design as a large unencumbered preaching hall ensured it remains as one our largest public spaces.

In 1861 the architect to the trustees of Norwich School, James S Benest, began renovations in preparation for the Commercial School that opened the following year. He faced the west elevation of the cloisters with polychrome brick [7]. His additions are in the Gothic Revival style, one of very few examples of its kind in the city.

Scott continued his education at Elmfield College on the outskirts of York (92 boarders, £31 fee). It was also known as Jubilee College in recognition of the Silver Jubilee of the Primitive Methodists in 1860.

Scott was a man of strong beliefs: he would not allow his children to be vaccinated against smallpox; he was a life-long sabbatarian, and a vegetarian on moral grounds. He also abstained from alcohol, which led to him turning down invitations to design licensed premises [8].

But high principle seems to have tipped over into irascibility. A letter from the Carron Foundry, who were casting windows for Scott, complained that they ‘exceedingly regret to note the tone in which you write’ [9]. Cromer historian Andy Boyce told me, “… on at least two occasions (Scott) went to court for minor assaults, usually regretting his actions and paying any costs. On one occasion he manhandled a lady when she wanted a railway carriage window shut because it was cold (he insisted it remain open)”. Scott also held back that portion of the rates used to support Anglican Schools. As a result, bailiffs would come to his house and take away his pictures but he always seems to have bought them back [8]. In 1969 Scott’s family gave one of his paintings to the Anglican cathedral. It is by Amelia Opie’s husband, John.

Scott furthered his career as an architect by studying the practical side of the building trade with George Skipper’s father, Robert, in East Dereham [2]. He then spent two years with John Henry Brown who – according to Pevsner and Wilson – was one of the architects responsible for meddling with the west front of the Anglican Cathedral [6]. After two years with the Liverpool Corporation, Scott had sufficient experience to start his own practice at 24 Castle Meadow Norwich. For 17 years of this period he was also Surveyor of Cromer.

Scott remained at the Castle Meadow office from 1886-1927. He was joined by his son Eric Wilfrid Bonning in 1910 and when another son, Theodore Gilbert, joined around 1918 the practice was restyled AF Scott & Sons. In 1927 the Scotts’ offices moved to 23 Tombland [10].

In June 1882, Augustus Frederic Scott married Emmeline Adcock. Around 1900, Emmeline’s younger brother, Edward O Adcock, was to establish a gigantic plant nursery off Upton Road (see recent post on plant nurseries in Eaton [11]).

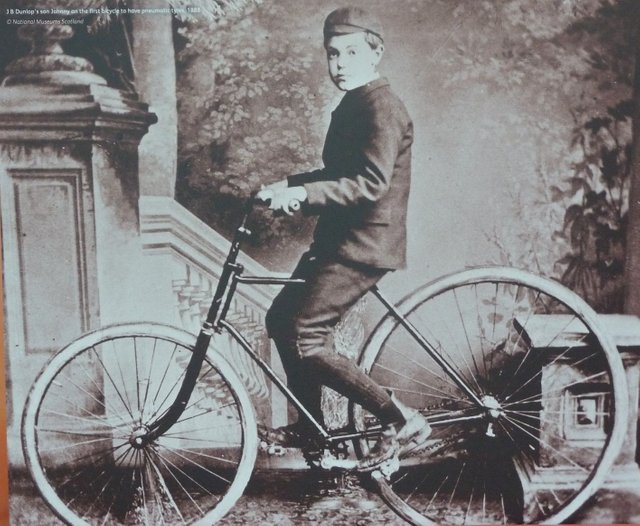

Augustus Frederic Scott was a familiar figure in his ‘wideawake’ hat with a three and a half inch brim that, from the defensive tone of his description, seems to have drawn comments. “My wide brimmed hat keeps off a certain amount of rain and sun and is of practical use. And moreover it suits me”[3]. He was also described as an enthusiastic cyclist, although the adjective doesn’t quite describe the arduous journeys on which he embarked in the early days of cycling.

Scott claimed to have had the first bicycle in Norfolk fitted with pneumatic tyres. He cycled to Kings Lynn to catch the early train to Doncaster as well as cycling from Norwich to his office in Holborn Hall, London [10]. John Boyd Dunlop was awarded the patent for his invention in 1888, which suggests that Scott’s long journeys were made when roads were largely unmaintained and probably unmetalled.

Despite the notable exceptions, which come later, Augustus Frederic Scott is known as the designer of numerous non-conformist chapels around the county. These are included in Norma Virgoe’s non-exhaustive list [8]:

West Acre (1887), Lessingham (1891), Garboldisham (1893), East Runton (1897), Postwick (1901), Lenwade (1905), Runhall (1906), Stokesby (1907), Billingford (1908), Fakenham (1908), Attleborough (1913), and Castle Street, Cambridge (1914) Primitive Methodist (PM) chapels, as well as Reepham (1891) and Cromer (1910) Wesleyan chapels. He also designed Cromer (1901), Dereham Road, Norwich (1904) and Wymondham (1909) Baptist churches. Lingwood PM Sunday school (1878) and Queen’s Road, Norwich PM Sunday school (1887) were of his design and so, too, were Wymondham Board School (1894), Ber Street, Norwich UM mission hall (1894-5), Botolph Street, Norwich clothing factory (1903), Bunting’s Department Store, Norwich (1911), Cromer cemetery chapel.

The first in that list is at West Acre in north-west Norfolk, now the home to the West Acre Theatre.

Before about 1840, non-conformist chapels were often rectangular and plain with the long wall as the dominant facade but through the nineteenth century the short gable end became the focal point [12]. Other denominations favoured Classical designs but through the nineteenth century until World War I the Methodists seemed to prefer the minority Gothic. And in his designs Scott showed an increasingly elaborate Gothicisation of the gable end as seen here in the Baptist church on Dereham Road. Pevsner and Wilson’s pithy entry reads: ‘Hectic Gothic front of brick and stone‘[7].

The same double-arched porch with a polished granite column, surrounded by Cosseyware diapering and crowned by a large window with Geometric Decorated tracery occurs repeatedly in Scott’s work. He used a very similar approach for the Methodist church in Attleborough, Norfolk, except the square tower was not extended by an octagonal lantern. Elsewhere he used variations on a theme – spirelets, pinnacles, turrets, steeples – to increase the upward movement of the gable end.

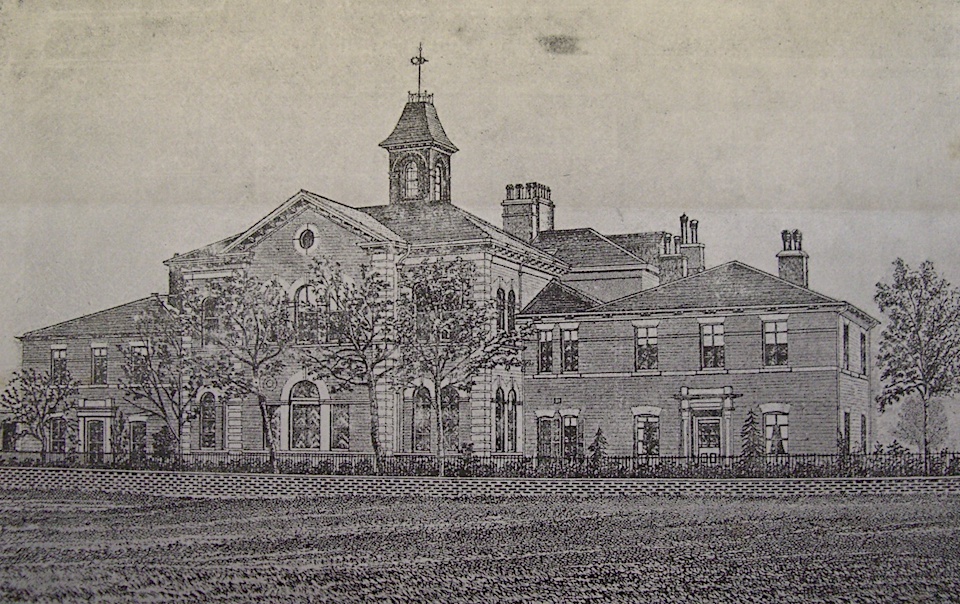

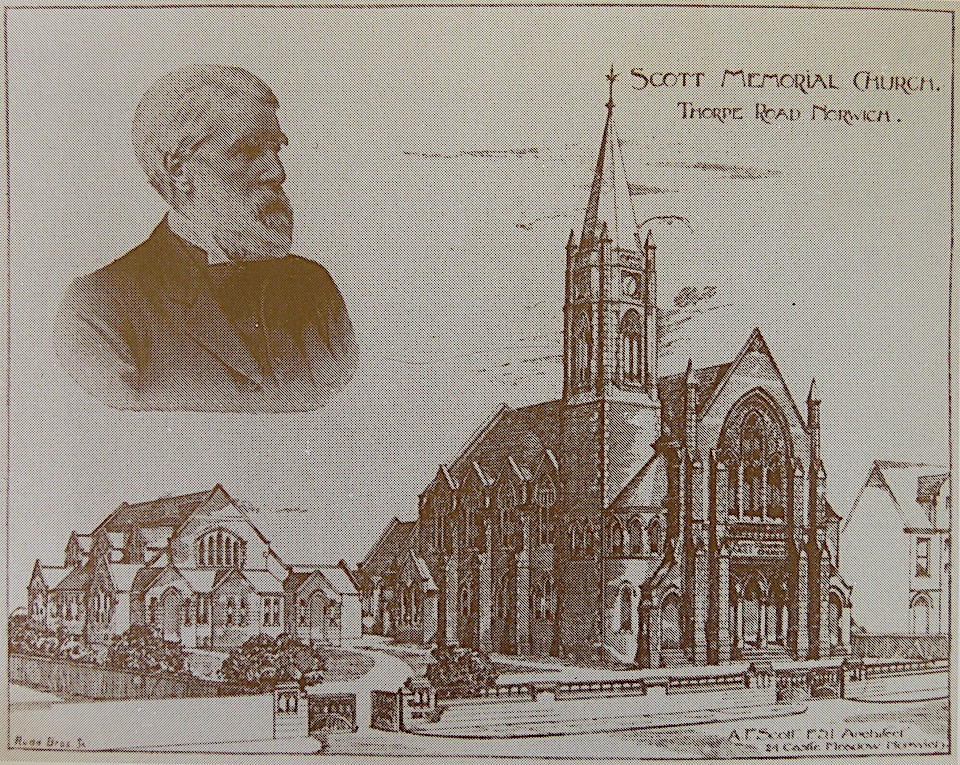

For 44 years, Augustus Scott’s father, Reverend Jonathan Scott, tended his congregation in Thorpe Hamlet, a suburb to the east of Norwich. Too poor to have their own church his parishioners were, in 1876, allowed to pray in Blackfriars Hall, once home to the city’s Dutch Protestant community (see OS map at top). Money was raised for a new Methodist church to be designed by AF Scott and dedicated to his father. The Jonathan Scott Memorial Church is perhaps Scott’s finest church, built of red brick with stone imported from Ancaster in Lincolnshire – a more magnificent version of his chapel built the same time on Dereham Road [2].

The original plan was even more ambitious but the steeple was never built. In 1920, Scott entered into a severe dispute with minister Percy Carden, causing the architect to sever relations with the church he’d designed to commemorate his father.

Most of Scott’s buildings were in Norfolk though he did venture further afield. He designed Primitive Methodist churches in Walberswick, Suffolk (1910), Cambridge (1914) and two Primitive Methodist churches in Lancashire, at Thornton (1904) and Fleetwood (1908) [8]. A strong family resemblance starts to show through Scott’s gable end facades. Compare the Fleetwood church below with the Scott Memorial Church in Norwich, above.

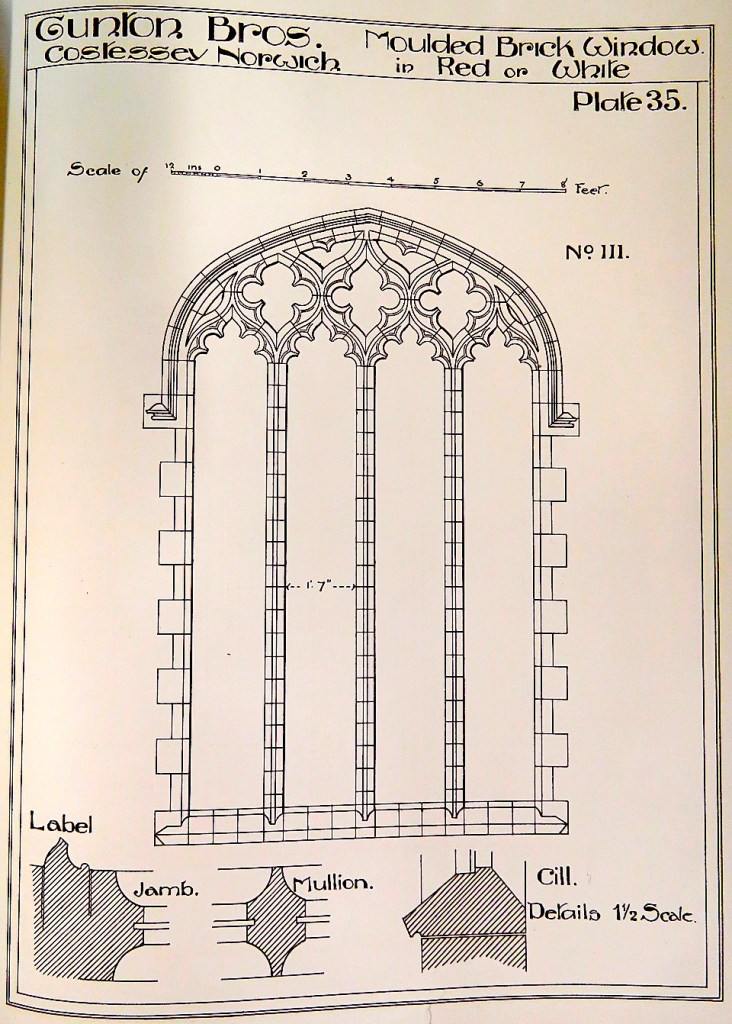

The white clay tiles on the church in Fleetwood (below) are identical to the kind seen at Attleborough (above). Scott’s practice necessarily had a close business relationship with ‘Mr Gunton, Cossey’. Hand-written letters show the architect asking for stop ends, mullions and string courses, describing pilasters and asking Gunton to ‘proceed with the Cossey Ware in white for the chapel’ [13]. By providing a ready shorthand for ‘Gothic’, Cosseyware had become an indispensable part of the architect’s palette.

The Guntons Brickyard at Costessey provided the Decorated tracery for instant Gothic, ‘in red or white‘.

Before leaving for Cromer, let’s look at the little Swedenborgian Church on Park Lane, around the corner from where I used to live [2]. The Swedenborgian sect had had several homes in the city and came to this street due largely to the efforts of James Spilling, editor of the Eastern Daily Press, who lived on Park Lane. Spilling was a preacher and follower of Emanuel Swedenborg (theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic) and raised money to build the little church. Scott was commissioned to design it in 1890. At one time Spilling preached in Glasgow: ‘Here the matter of his discourses gave the greatest satisfaction, but his East Anglian pronunciation was regarded as a drawback to his selection as its minister’ [14]. (After posting, follower Paul Reeve commented, ‘The Swedenborgian chapel on Park Lane was eventually bought by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in the 1920s, and was their Norwich chapel until 1963 when they built a new complex on Greenways, Eaton, selling the Park Lane building to the Haymarket Brethren. Eventually it was sold to the owner of the house next door, who uses the former chapel for concerts.’)

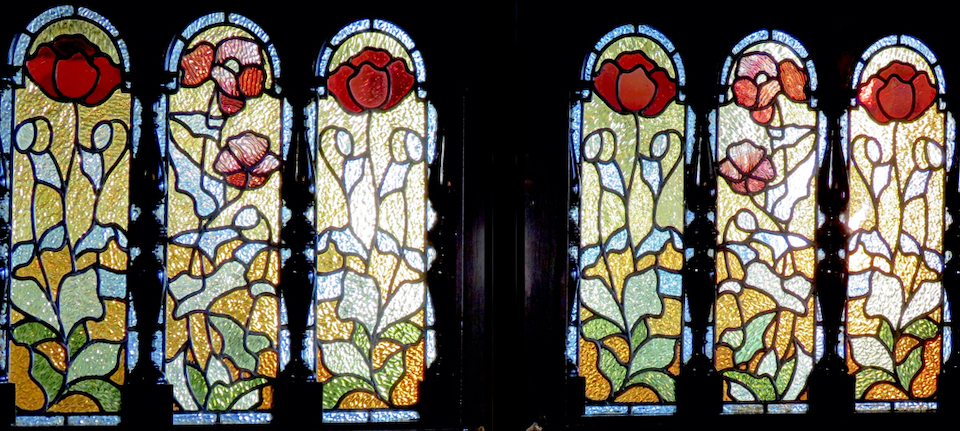

Cromer became a boom town after the railway arrived in 1877 – its attraction boosted by ‘Poppyland’ columns in the Daily Telegraph in which Clement Scott (no relation) portrayed a North Norfolk idyll. George Skipper designed hotels here [15]. AF Scott & Son also designed hotels here but they must have been outraged when, just four years after the completion of their Cliftonville Hotel, rival Skipper was invited to give it an Arts & Crafts makeover. Skipper extended the hotel and altered the sea-facing facade, adding art nouveau touches in Cosseyware carved by James Minns of Norwich.

Scott also designed the Eversley Hotel, which is now flats.

Scott was Surveyor to Cromer Urban District Council and for a while ran his private practice from Church Street [16]. In addition to the hotels, he designed Mutimer’s department store, the old fire station, shops and houses. He also designed Cromer Cemetery Chapel, which gave him the steeple denied at the Scott Memorial Church.

In 1909-10, AF Scott built Cromer Methodist Church in red brick.

Whenever I have driven down the hill into Cromer I have been intrigued by two very similar turreted houses flanking the entrance to Cliff Avenue. Now, with my head full of the spires and turrets of AF Scott I wondered if they could be further examples of the architect’s work.

It had been suggested that this non-identical pair of houses was by Scott [17] but local historian Andy Boyce now believes the attribution may not be correct.

Cliff Avenue is a late Victorian time capsule of fashionable housing for the affluent. Built between 1893 and 1905, it displays hallmarks of the Queen Anne Revival style although, a decade or so after the pioneering Bedford Park in West London, it represents a comfortable, more diluted version or, as Marc Girouard called it, ‘Queen Anne by the Seaside’ [18]. Expect to see red brick with white-painted trim, bay windows, monumental chimneys, hanging tiles and verandas.

While he was Surveyor of the Board (the predecessor to Cromer Urban District Council) Scott also designed several private houses in Cliff Avenue. Some members of the Board saw this as a conflict of interests but Scott replied that ‘When he agreed to take on the Surveyorship at such a low salary he expected that out of sympathy for him the Board would have placed private work in his way… he could not be expected to give his whole time for £45 a year’ [17]. A letter to the local paper complained that houses on Cliff Avenue were being built for a member of the Board by the Deputy Clerk to the Board under the supervision of the Surveyor of the Board (Scott). Moreover, the houses didn’t comply with the unpopular bye-laws that Scott had helped promote. A residents’ committee wanted to remove him as Town Surveyor [17].

These houses for Cromer’s well-to-do were, like Scott’s churches, comfortable (that word again), even formulaic. It is hard to reconcile this side of his work with his excursions into the modern that we see elsewhere. The technology for reinforcing concrete with steel was developed in Europe and used in Britain in the 1890s. In 1903, Scott designed the first building in Norwich to be constructed with this material – Roberts’ print works in Botolph Street. Pevsner [7] thought it was the most interesting factory building in Norwich and an early example of European Functionalism, but this didn’t prevent its destruction in 1967 to make way for Sovereign House and Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Listed for ‘its early contribution to the early development of the modern movement in England‘ is the old Citroën garage in Kings Lynn, formerly the Building Material Company. Heritage England say this is probably to a design by AF Scott [19]. Constructed in 1908, this early example of a concrete-framed building boldly displays its structure without the need for disguise.

When Scott built a new department store (1912) in Norwich for Arthur Bunting [1] he designed a framework of reinforced concrete to which he attached a stone curtain-wall decorated – rather incongruously – with carved Adam swags. In 1942, German bombs devastated other buildings on St Stephens Plain. The non-structural walls of Buntings were blown out but the concrete skeleton withstood the blast, remaining as the basis for rebuilding. Minus the third floor and its corner cupola it is now a branch of Marks & Spencer.

There are fleeting mentions of AF Scott in his latter years. There is a suggestion [2] that he was the architect of the Kiltie shoe factory in Norwich-over-the-Water; more certainly he was one of four local architects (including George Skipper) who were invited in the 1920s to design houses for the Mile Cross estate just north of the city [20], although it isn’t known which bear his signature. Augustus Frederic Scott died in 1936 but he had not been involved in the practice for a number of years. His sons continued as A.F.Scott & Sons and it was Eric Scott who designed the Debenhams building on Rampant Horse Street in the mid-1950s. The business was amalgamated with Lambert & Innes in 1971, forming Lambert Scott & Innes who, now as LSI Architects, have offices at the Old Drill Hall on Cattlemarket Street.

©Reggie Unthank 2021

Sources

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2021/04/15/norwich-department-stores/

- Rosemary Salt (1988). Plans for a Fine City. Pub: Victorian Society East Anglian Group.

- AF Scott obituary, ‘The Journal’ April 4 1936, p15. From britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norwich_School

- http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk/norwich_maps/norwich_maps_finder.shtm

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1220456

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (2002). The Buildings of England. Norfolk I: Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- Norma Virgoe (2016). Augustus Frederic Scott: A Norwich Architect in Lancashire. In, Lancashire Wesley Historical Society. Bulletin 62. pp21-24.

- Correspondence about the Co-op stables on All Saints Green, designed by AF Scott. Norfolk Record Office BR 309/1.

- https://nrocatalogue.norfolk.gov.uk/index.php/records-of-a-f-scott-architect

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2021/01/15/the-nursery-fields-of-eaton/

- https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/iha-nonconformist-places-of-worship/heag139-nonconformist-places-of-worshipi-iha/

- Copies of Scott letters 1894-5. Norfolk Record Office MC 941/1, 810×6

- https://www.norwichchapelconcerts.org.uk/history-of-the-chapel

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/02/15/the-flamboyant-mr-skipper/

- Cromer Preservation Society (2013). Cobbles to Cupolas: an introduction to buildings in Cromer town centre. CPS Guide #1

- Cromer Preservation Society (2010). Holiday Queen Anne: the villas of Cliff Avenue. CPS Guide #5.

- Marc Girouard (1984). Sweetness and Light: The Queen Anne Movement 1860-1900. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1459413

- Mile Cross Conservation Area Appraisal #12, June 2009. Norwich City Council.

Thanks

I am grateful to Peter Forsaith, Research Fellow at The Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History at Oxford Brookes University for information on Scott’s connection with Lancashire. Andy Boyce, local historian of Cromer, provided background on Cliff Avenue. Pike Partnership provided background on the Cromer Methodist Church. Stuart McPherson (The Mile Cross Man) advised on the Mile Cross Estate. Alan Theobald is thanked for discussions.

The Swedenborgian chapel on Park Lane was eventually bought by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in the 1920s, and was their Norwich chapel until 1963 when they built a new complex on Greenways, Eaton, selling the Park Lane building to the Haymarket Brethren. Eventually it was sold to the owner of the house next door, who uses the former chapel for concerts. http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/norwichsweden/norwichsweden.htm

LikeLike

Thanks Paul, I’ve updated the post with your fascinating comments. Reggie

LikeLike

Another fascinating piece, thanks! And I shall look at the Castle Hill Methodist church with much more attention, if I ever get to the other side of Cambridge again …

LikeLike

Hi Caroline, I had planned to come over to Cambridge to photograph the chapel but never quite made it. Reggie

LikeLike

Hi Reggie, very interesting, we knew his

grandson John Scott, also an architect,

the last Scott architects. He was partner

at Lambert Innes and Scott. He was married

to Daphne who was Dutch.

LikeLike

Hi Maarten, Good to hear that the Dutch/Norwich alliance is still going strong. Reg

LikeLike

What an interesting man! I can imagine he must have been very hurt and angry when The Cliftonville Hotel was made over. Such a cruel thing to do to an architect of his standing.

LikeLike

Hello Clare. Yes, it seems cruel to have given such a makeover to an arch-rival for grand projects in Cromer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fabulous article, Reggie. Thanks for sharing your hard work. I have happy memories of Kingswear in Cromer where my grandparents lived for about 40 years.

LikeLike

Kingswear is such an interesting building, John. I wonder who did design it. Cliff Avenue was a fascinating discovery, with its Scott buildings – a time capsule of Edwardian England. Reggie.

LikeLike

A F Scott rarely gets the same attention as Skipper and Boardman but many of his buildings have stood the test of time very well. The loss of the Roberts Printing Works was a great shame. Between them Scott and Boardman seem to have designed most of the Non-Conformist chapels in Norfolk and kept the Cossey brickworks in business.

This post could be a basis for a wider study of Scott’s work – once again a great piece

LikeLike

Hello Don, Scott certainly deserves to be thought of alongside Skipper and Boardman as someone who left his imprint on the city.

Reggie

LikeLike

Pingback: Cecil Upcher: soldier and architect | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

A nice panorama of Scott’s work. the Modernist buildings being to my mind the most valuable part of his output. The various Nonconformist Chapels are much redeemed by the Cosseyware. Just imagine the (rather sweet) Cromer Baptist Church in Ruabon brick. We have at least been saved from the Lobster Gothic!

My grandfather was chief compositor and later secretary for Roberts’ Printers,( others in the family worked for the opposition- Jarrolds) so, as a kid I got to know Scott’s factory quite well, often reading their latest publications “hot off the press”! I think the works, bold and unfussy, were originally built as a warehouse for Buntings, yes? and merit an admiring photo in my trusty Pev. (first edition). Our family hub, so to speak, was just off Magpie Road, so we all witnessed, over the ’60s, the long drawn out, shabby destruction of this part of Norwich over the Water. What still rankles after half a century is the way in which they demolished nearly twice the actual area that they needed, and that this still lies unused. Can’t HMSO be compelled to demolish Sovereign House for safety reasons- the whole building is, literally rotting- or are Government departments these days exempt from even basic planning regulations?

LikeLike

Fascinated to hear you have a family connection to Roberts printers who commissioned that very modern building from AF Scott. You are right to feel aggrieved about the over-destruction of the site that gave rise to Anglia Square. There are so many lessons to be learned here about how developments succeed best when they are sensitive to their surroundings.

LikeLike

Pingback: Gothick Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH