An unintended consequence of the puritanical whitewashing of brightly coloured Catholic imagery on church walls was that it liberated vast acres to be colonised by hanging monuments. We see this at Saints Peter and Paul, Heydon, where cleaning work in 1970 revealed sequences of fourteenth century wall paintings that had been unwittingly obscured by later stone memorials.

In the previous post we saw the ‘kneeler’ monuments as grand floor-standing memorials but by flattening the perspective this theme could be readily adapted to slimmer wall-hung memorials. St John Maddermarket, one of the most intriguing churches in the city, contains the memorial to Christopher Layer (1533-1600), wealthy grocer, sheriff, alderman and twice mayor. On this wall monument, rich in symbolism [2], we see unbiblical motifs. The two uppermost statuettes in the niches are Roman (Pax and Gloria). The task of the slave accompanying the conquering hero on his triumph through Rome was to whisper in his ear, ‘Memento mori’ (remember that you must die). A similar purpose is served in this monument by the skull that hovers between husband and wife, warning against seduction by the transient vanities of life. The putto holding a bubble (lower left) is another much used symbol of the kind seen in Dutch vanitas paintings of the period. The reward for treading the middle way is, as we see at the top of the painting, entry into heaven.

Kneeler monuments were still commissioned towards the end of the seventeenth century, as in this memorial to Sir Thomas Greene in St Nicholas’ Chapel, Kings Lynn. Another merchant made good, Greene (d. 1675) was three times mayor. The effigies of Greene and his wife Susannah Barker no longer look at one another across the prayer desk. The faces are fascinating; they are clearly portraits of citizens who have done well in the world but, with puritanical restraint, are shown as plain folk, warts-and-all. The vanitas element is still present in the skull that separates the five daughters and four sons below, although the humility is somewhat checked by the splendour of the coat of arms above.

Pevsner and Wilson [3] attribute the Greene Monument to London mason, Thomas Cartwright the Elder, who worked with Sir Christopher Wren. Mortlock and Roberts [6], on the other hand, suggest local architect Henry Bell, providing me with an excuse to show his sublime Customs House on Kings Lynn Quayside.

In the same period as Greene’s puritanical kneeler, a far more sumptuous structure was erected for Sir Thomas and Lady Adams in Sprowston – now a northern suburb of Norwich. The contrast between Roundhead and Cavalier, new money versus old, is stark. Sir Thomas had been an intimate friend of King Charles II and rose to be Lord Mayor of London. Husband and wife semi-recline on separate levels with her, unusually, occupying the upper berth where she strikes a pose described as ‘precious and unrestrained’ [3]. Poor Sir Thomas suffered from the stone, something common in Norfolk and was much operated upon by Dr Rigby when the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital opened a century later. After death, Sir Thomas’ kidney stone was found to weigh just over a pound and a half.

Below, this sculpture from the latter part of the seventeenth century shows the lingering influence of kneeler monuments. The angel flying across the black tablet carries away a chrysom child in its swaddling cloth, sowing confusion in the minds of those trying to read the inscription. You will search in vain for Sir William Heveningham’s name, it doesn’t appear here nor on his tomb slab in St Peter’s Ketteringham. Sir William was one of the judges at King Charles I’s trial. He didn’t sign the death warrant but, after the Restoration, was convicted of high treason and his lands seized by the Crown. His life was spared and through the exertions of his wife – Lady Mary Heveningham, daughter of the Earl of Dover – the estate was recovered. She erected this family monument but her husband’s name is absent [4].

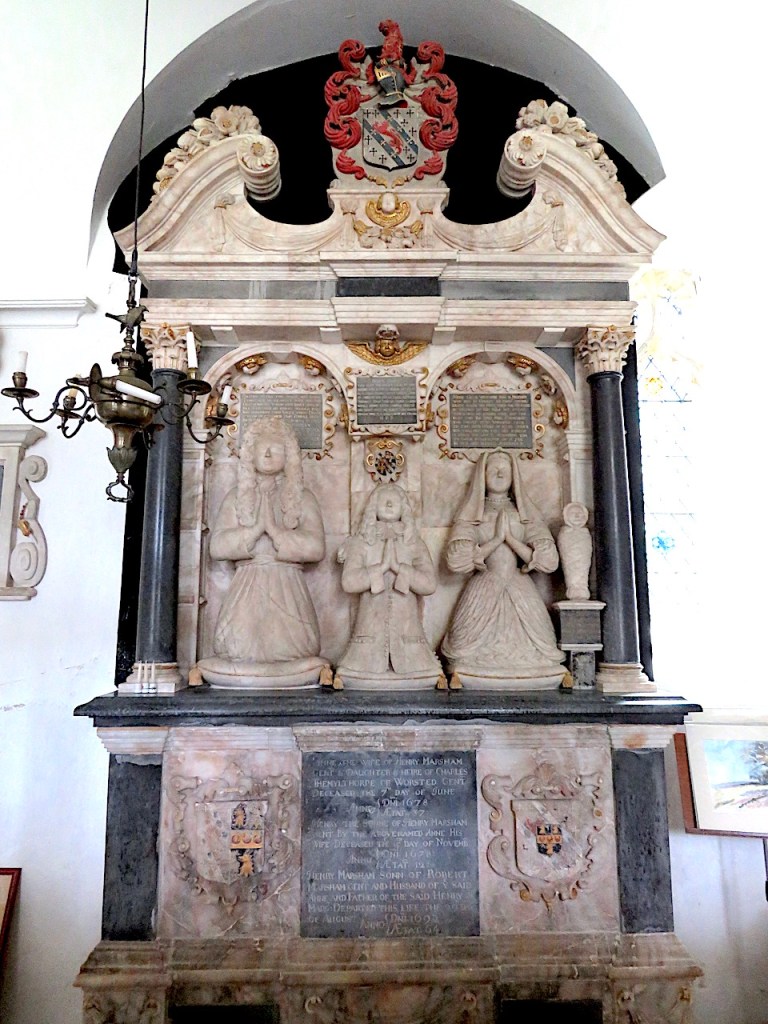

Back to Stratton Strawless and the tomb of Henry Marsham (1692); a Classical backdrop, all Corinthian columns and scrolly pediments. The kneeling figures are Henry, son Henry and Anne Marsham (plus baby Margaret, upright in her swaddling sheet) but, in order for all of them to kneel in this narrow recess, they turn to face us, causing Spencer [5] to wonder what happened to their legs and feet.

In the 1700s, chest tombs ‘faded from the picture in favour of wall monuments and tablets more restrained than those of the C17’ [3]. Elements of Classicism, already established in the previous century, came to the fore. To put this period into local historical perspective, this was a time when Holkham Hall was built in the Palladian style – a purer version of Classical than the Baroque. The outstanding London sculptors of their age, Frenchman Louis François Roubiliac (1702-1762) and the Flemish emigré, Michael Rysbrack (1694-1770), were never commissioned to build tombs in Norfolk. Roubiliac did, however, sculpt the busts of Lord Leicester, Thomas Coke (d. 1759), and his wife on their monument in Tittleshall.

The Tittleshall monument itself is attributed to Charles Atkinson, responsible for carving most of the chimneypieces at Holkham [3].

To the right of this monument is the work of Joseph Nollekens, one of only two pieces by him in the county. Just sneaking into the next century (1805) is the bas relief to Jane Coke, wife of the great agriculturalist, ‘Coke of Norfolk’. The fashionable London sculptor Nollekens was to sculpture what Sir Joshua Reynolds was to portraiture [6].

Once apprenticed to Nollekens, the Flemish sculptor Peter Scheemakers was best known for his sculpture of Shakespeare in Westminster Abbey. His studies of Baroque and Classical sculpture in Rome helped him influence the development of modern sculpture in England [7]. His only work in Norfolk is this large monument to Susannah Hare (d.1741) in Holy Trinity, Stow Bardolph [6]. The reclining figure is rare after this date [3].

The Hare Mausoleum, built in 1624 by John Hare on the north side of the chancel of Holy Trinity Stow Bardolph, houses perhaps the most curious memorial in the county. This is the wax effigy of Sarah Hare in her mahogany case, emerging from behind curtains. She died of blood poisoning after pricking her finger while embroidering and it was her wish to be remembered in her everyday clothes. The model is unflattering and the effect of her gaze is variously described as ‘shattering’ and ‘terrifying’ – an antidote to the saccharine (or, at that time, sugar-laden) memorials that try to dissemble the reality of death.

Norwich mayors were elected annually. In life, their parish churches would have celebrated by adding their name plaque to ceremonial sword and mace rests (and Norwich probably has more of these than anywhere outside London [8]) while in death their achievement might be recognised by a wall tablet.

Very few eighteenth-century mayors had sufficient influence in death to command floor space in their place of worship but parish churches like St George Tombland began to fill with mayoral wall monuments. Norwich is said to have had more than a score of sculptors who could produce the increasingly popular wall tablets ‘equal in standard to the best London work’ [5]. From the pool of ‘Norwich School’ sculptors Spencer picked out Robert Page (1707-1778) [9] and Thomas Rawlins (1747-1781) [10]. He excluded Robert Singleton (1706-1740) [11] from the Norwich elite only on the grounds that he came from Bury St Edmunds. However, Singleton had a workshop adjacent to the Cathedral and was master to Page the apprentice and deserves to be in this group. Another member of this top tier of Norwich monumental masons was John Ivory, nephew to Thomas Ivory, the architect of Georgian Norwich (Octagon Chapel, Assembly House).

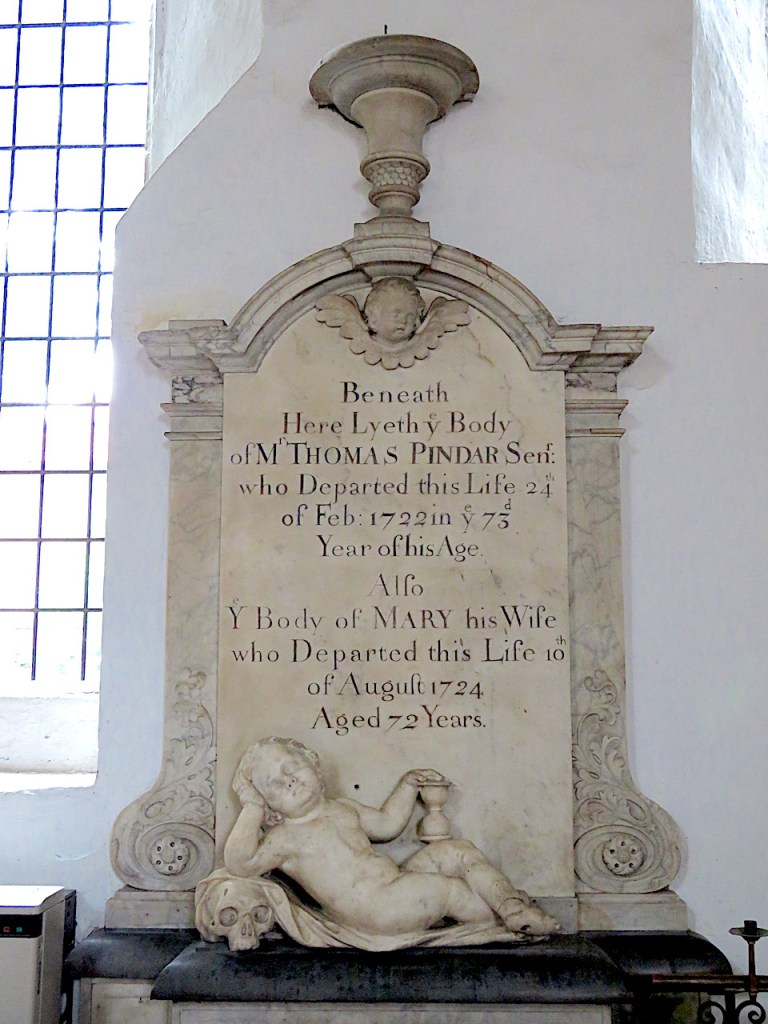

A simple but charming wall monument by Singleton is in St George Colegate. Almost in parody of the lolling pose a cherub rests on a skull while holding an hourglass.

Robert Page has been described as the best sculptor that Norfolk has produced. As we can see from this wall monument in SS Mary and Margaret, Sprowston, his work is characterised by the use of colourful marble veneers and the appearance of ‘delightful’ cherubs [5].

In St Andrew’s Norwich, Page’s tablet commemorating Thomas Crowe contains three cherub heads that so pleased Noël Spencer (‘the most delightful I have ever seen’) that he employed them on the frontispiece of his book [5]. In the absence of sculpted portraits, flocks of cherubs, seen in their hundreds on Georgian and Victorian memorials, satisfied the need for a figurative presence.

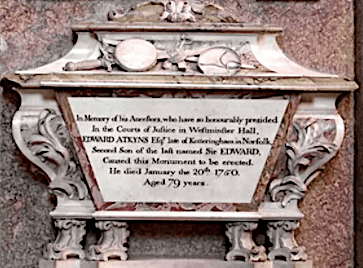

Page was also known for carving handsome sarcophagi [5]; a particularly fine example, with detailed lions’ feet, memorialises Edward Atkyns (d.1750), Lord of the Manor at Ketteringham. The end of a sarcophagus projects part way out of the wall, showing how the narrow end of a sarcophagus or casket came to provide the format – lozenge or rectangle – for less florid wall tablets.

As spotted by church warden Mary Parker when viewing an interview with the Duchess of Cornwall on TV, a near identical inscription celebrating the Atkynses of Ketteringham can be seen in Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey – this by Sir Henry Cheere, ‘carver’ to the abbey. Apart from the generic sarcophagus theme, this monument of 1746 is stylistically different from the one attributed to Page at Ketteringham.

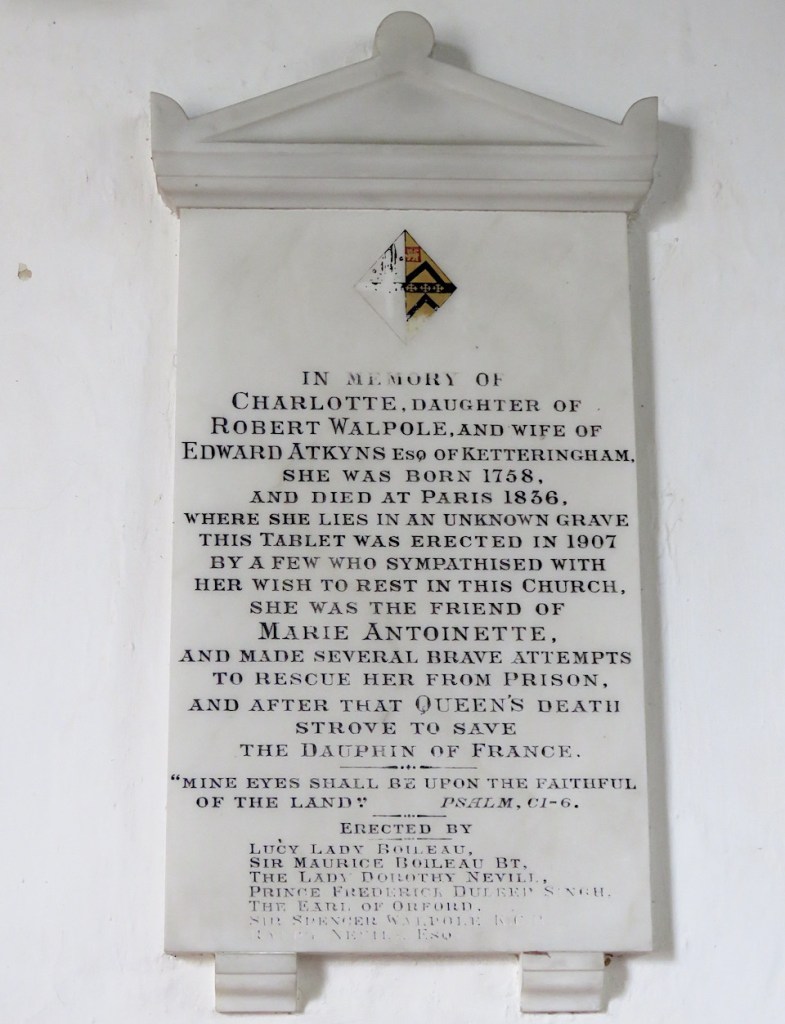

Edward Atkyns (d.1794), a later lord of the manor at Ketteringham, scandalised the county by marrying an Irish actress, Charlotte Walpole, who performed at Drury Lane.

Shunned by the local squirearchy, they moved to France where she became friends with Marie Antoinette and is said to have squandered the family’s money in plots to release the queen and her son, Louis XVII, from prison. In one account Charlotte – reprising her performance at Drury Lane – dressed as a soldier of the National Guard in order to free the unfortunate queen. The romantic story of her escapades in Paris appears in the book ‘Mrs Pimpernel Atkyns’ by EEP Tisdall [12].

Trained in London, Thomas Rawlins worked from 1743 to 1781 as a monumental mason in Norwich, based in Duke’s Palace Yard on the site of present-day St Andrews Car Park. Rawlins’ work was thought to be among the best, not just locally, but on the national stage [13]. This blowsy wall monument to the wonderfully named Hambleton Custance in St Andrew’s Norwich, shows the contemporary fascination with coloured marble and cherubs.

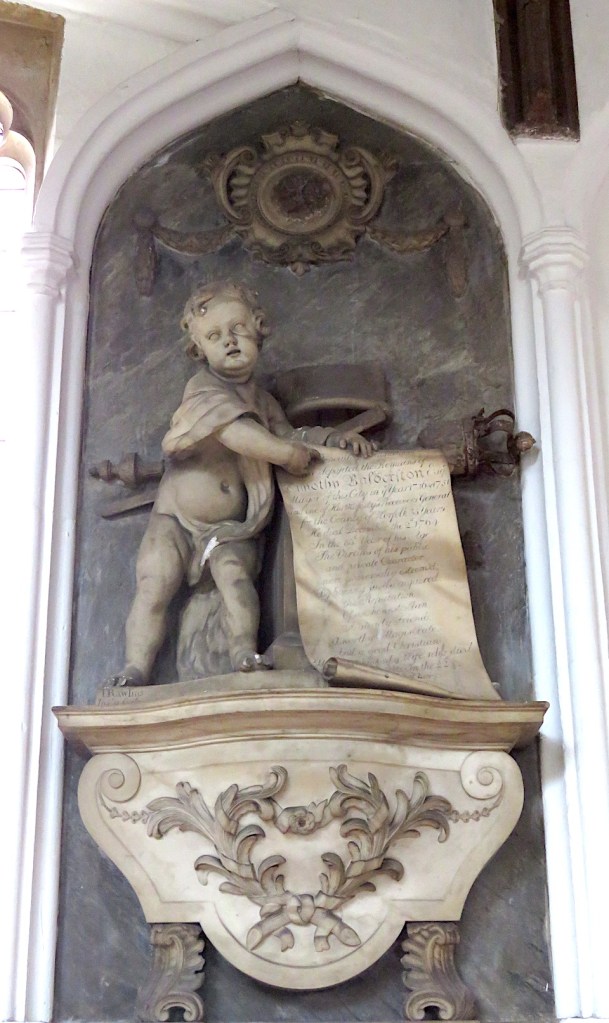

The Georgian wall monument by Rawlins in St George Colegate commemorates two-times mayor Timothy Balderston (d.1764). The mayor’s sword and mace lie behind the cherub who points to Balderston’s eulogy on the scroll.

John Ivory (1730-1805/6) – ranked by Pevsner below Page and Rawlins [3] – took over Page’s shop and yard at the corner of King Street and Tombland, just outside the cathedral’s Ethelbert Gate. Now the site of the All Bar One restaurant, this was roughly where the Popinjay Inn stood, the origin of the great fire of 1507 that burned 718 buildings [14]. Probably Ivory’s best monument (‘a very fine architectural tablet’ [3]) was made for Charles and Mary Mackerell in St Stephen’s Norwich.

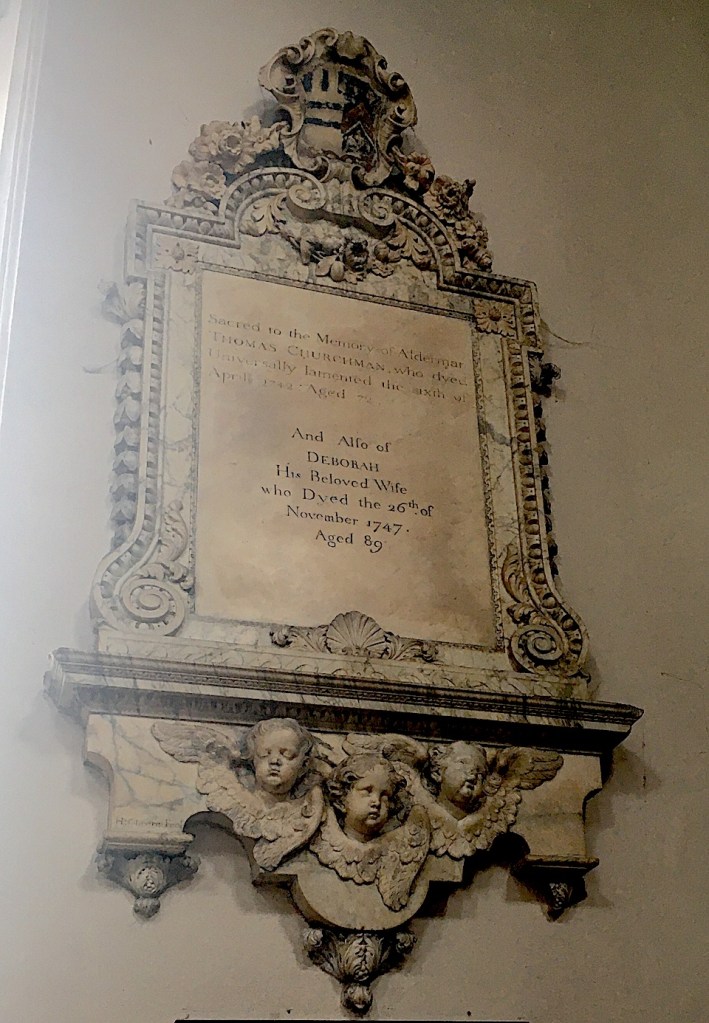

After I had written this post I unexpectedly found St Giles Norwich open and snapped this wall tablet by Sir Henry Cheere with my ancient phone. It commemorates Sir Thomas Churchman (d 1747) who lived in ‘One of the finest houses in Norwich’ [3] – Churchman’s House on the opposite side of St Giles Plain. Both this and the Ivory monument above were made around 1747. They follow a very similar pattern, allowing the work of one of the city’s leading sculptors to be compared favourably with the output of Westminster Abbey’s carver.

At the very end of the eighteenth century, Ivory carved ‘a pretty memorial’, with vases straight out of the Wedgwood catalogue. This monument to Mary Evans, daughter of the man who had Salle Park built in 1761, is to be found in SS Peter and Paul, Salle.

The Classical influences that dominated the Regency period lingered until the time of Queen Victoria’s accession (1837) after which, according to Spencer [5], there was an aesthetic decline. He named three sculptors most representative of this period: John Bacon the Younger (1777-1859); Sir Richard Westmacott RA (1775-1856); and John Flaxman (1775-1826), most widely known as a modeller for Wedgwood.

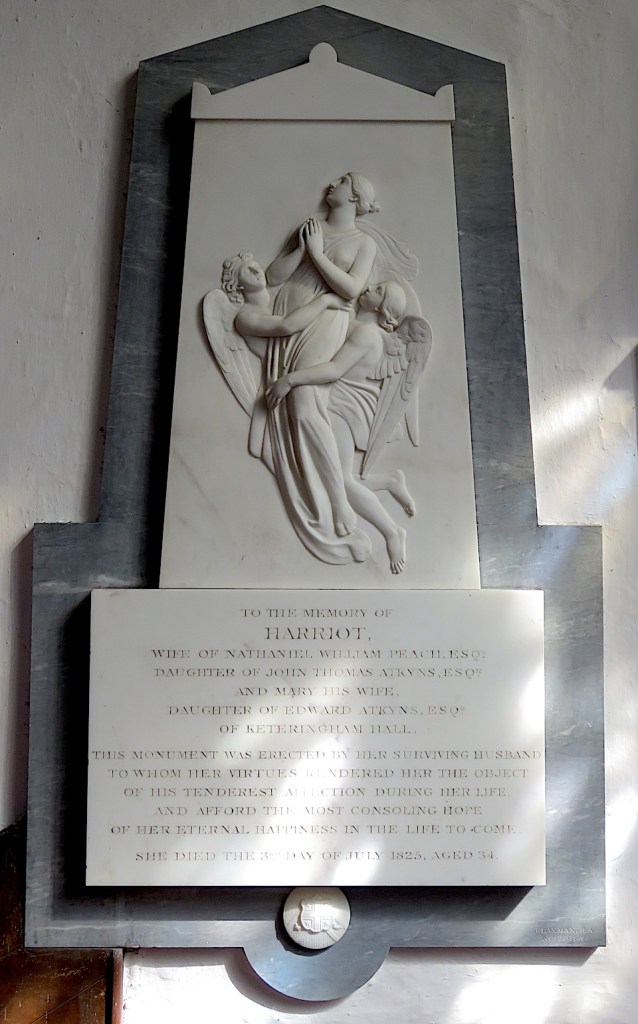

A favourite motif of Flaxman’s, a young woman carried heavenwards, appears on the elegant memorial for Harriot Peach (d.1825) at Ketteringham church. It is reminiscent of the Nollekens group that we saw at Tittleshall.

John Bacon Junior had been a child prodigy, sculpting monumental works from the age of 11 [13]. Here, he sculpts Lady Maria Micklethwait of Sprowston and her journey to heaven (1805). Compare this with the pared back simplicity of Flaxman’s similar theme, above.

John Bacon Jr also carved a fine monument in St George Colegate to Mayor John Herring (d.1810). A plain-speaking man, Herring twice declined to be knighted by the king, declaring himself unworthy of the honour.

Sir Richard Westmacott RA sculpted this monument to Edward Atkyns (d. 1794) and his son Wright Edward Atkyns (d. 1804) in one of Norfolk’s most fascinating churches – St Peter’s Ketteringham. The scene depicts a young woman mourning at the foot of a broken column crowned by weeping willow [3]. The martial symbols refer to the younger Atkyns’ career as Captain of Dragoons.

From its inception in the 1830s, the Anglo-Catholic Oxford Movement raised ideological objections to large and boastful monuments, creating the climate for a countrywide proliferation of wall tablets ‘but hardly anything bigger’ [3]. Classical design was considered pagan so religious buildings were to be in the Gothic style and certainly no later than Decorated. In Norwich, local tradition influenced the celebration of death (see The Norwich Way of Death [15]). Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the city’s population contained a high percentage of Dissenters. An Act of 1836 allowed Nonconformists to perform their own funeral services but it was not until 1880 that they were allowed to conduct burials in parish churches according to their own rites. However, in 1819, Thomas Drummond had established The Rosary Cemetery in the Norwich suburb of Thorpe Hamlet – the first in the country where anyone could be buried regardless of their religion. As a result, the monuments in The Rosary are gloriously various, some of them undoubtedly on the Oxford Movement’s proscribed list.

Jeremiah Cozens (d. 1849) has the only cast-iron sarcophagus at The Rosary …

… and the only mausoleum at The Rosary belongs to Emanuel Cooper, an eminent eye-surgeon (d. 1878). This is one of five C19 mausoleums in Norfolk [5].

Below is the memorial to John Barker, Steam Circus Proprietor (d 1897). The showman was crushed between two traction engines when setting up a ride at the old Norwich Cattlemarket (now Norwich Castle Gardens) [16]. He left 15 children.

In the municipal cemetery at Earlham a horse marks the grave of horse dealer John Abel and his wife Frances [17].

© Reggie Unthank 2021

Thanks: I am indebted to Dr Mary Parker, churchwarden, for sharing her extensive knowledge of St Peter Ketteringham. Simon Knott is thanked for kindly providing photographs.

My new book (click this link for preview) is available at £14.99 from Jarrolds of Norwich and the City Bookshop, both of which do mail order. It can also be found in The Book Hive Norwich, Waterstones Castle Street Norwich, Kett’s Books Wymondham and The Holt Bookshop.

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Three_Dead_Kings

- Kevin Faulkner (2013). The Layer Monument. Pub: Kevin Faulkner. Printed by Pride Press Ltd., Norwich.

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk I: Norwich and North-East and 2: North-West and South. Pub: Yale University Press.

- Joseph Hunter (1851). The History and Topography of Ketteringham in the County of Norfolk. Printed in Norwich by Charles Muskett.

- Noël Spencer (1977). Sculptured Monuments in Norfolk Churches. Pub: Norfolk Churches Trust.

- D.P. Mortlock and C.V. Roberts (1985). The Popular Guide to Norfolk Churches. No 3 West and South-West Norfolk. Pub: Acorn Editions.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Scheemakers

- https://shinealightproject.wordpress.com/2013/11/22/sword-rests-mace-rests-and-civic-ceremony/

- http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk/monuments/Robert%20Page/Robert%20Page.shtm

- http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk/masons/Thomas%20Rawlins/Thomas%20Rawlins.shtm

- http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk/masons/Robert%20Singleton/Robert%20Singleton.shtm

- E.E.P. Tisdall (1965). Mrs ‘Pimpernel’ Atkyns. Pub: Jarrolds, Norwich.

- Mortlock and C.V. Roberts (1985). The Popular Guide to Norfolk Churches. No 2 Norwich, Central and South Norfolk.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/12/15/norwich-shaped-by-fire/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/10/15/the-norwich-way-of-death/

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2109744

- Judith Havens (2014). John Abel: Horse-dealer of Norwich. Pub: Judith Havens.

I was fascinated by Edward Atkyns story. Wasn’t Robert Walpole father the prime minister. Did he live in Ireland? Not come across the spelling of Atkyns before.

LikeLike

Hello Rose, It’s worth trying to get hold of the book on Marie Antoinette’s would-be saviour. And no, he wasn’t that Walpole. Reg

LikeLike

Fascinating, thanks! (I must get out more …) Talking of bubbles, have you seen the Sutton monument in the Charterhouse? https://bit.ly/2UqvAx7

LikeLike

Just looked at your great post on a similar subject. The boy with the bubbles on the Sutton memorial is fabulous.

LikeLike

This excellent post will enliven my attendance this Sunday at a christening in St Mary and St Margaret Sprowston – in spite of the occasional wedding or funeral in this church over the years, I have neglected to examine the memorials. I always feel that St John Maddermarket is rather neglected in favour of some other churches in Norwich so please continue to draw attention to its splendours

Don Watson

LikeLike

Thank you Don. I am very fond of the interior of St John Maddermarket with its eclectic borrowings. Eyes peeled for the Sprowston monuments this Sunday.

LikeLike

What a beautiful memorial commissioned by Thomas Browne Evans for his wife, Mary! Thomas is said to have been the second cousin of Ann May (wife of William Unthank) but so far I haven’t been able to trace the connection. By the way, I’m enjoying your latest book which arrived safely by mail from City Bookshop.

LikeLike

The Ivory monument to Mary Evans is fine and restrained. If a connection does exist with the Unthank family, you – as a seasoned Unthankologist – will find it, I’m sure, Pam.

LikeLike

Made me laugh…an Unthankologist sounds a bit like a Bunburyist! Anyway, I’ll do my best and let you know if I crack the case.

LikeLike

An interesting read. good to learn more about some of these memorials. Thank you.

LikeLike

As a photographer, you must have seen these and more so thank you for the kind comments.

LikeLike

All these wonderful monuments have me hankering for a church tour of Norwich and Norfolk. Not yetawhile I think, as lack of fuel has been added to the equation!

LikeLike

Yes, we’ll have to restrict our forays to cycle rides until the Army get their 80 petrol tankers going.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Noël Spencer’s Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH