Tags

Alfred Russel Wallace, Charles Darwin, Dawson Turner, James Edward Smith, Joseph Dalton Hooker, The John Innes Centre, The Lindley Library, The Royal Society

There was a time when investigating the world around you could be a dangerous thing: think of Galileo’s unpleasantness with the Inquisition for suggesting that the Earth might not be the centre of the Universe. Locally, on a more humble scale, a group of Norfolk botanists [1] were at the forefront of systematic plant classification; they may have thought they were simply revealing God’s plan but this was part of a larger movement from which the Theory of Evolution emerged, undermining the idea that all living things were made on just two days of Creation.

The Meaning of Life. © Universal Pictures

Not long after the Galileo Affair, the Norwich physician Sir Thomas Browne (1605-82) was making systematic observations on the natural world, leading to the first attempt at listing Norfolk’s birds. He was succeeded by a network of local collectors who did the same for plants.

Sir Thomas Browne, not far from his house in Haymarket, Norwich, contemplates an Anglo-Saxon burial urn found in a field at Brampton, Norfolk

In the C18 Robert Marsham (1708-97), son of a Norfolk landowner, began to make ‘natural calendars’ in which weather and temperature could be correlated with the arrival of birds and the emergence of plants [1]. Over a 60 year period Marsham maintained tables of ‘Indications of Spring’, helping to establish the science of phenology that deals with seasonal and cyclic effects of climate on the natural world.

‘The Father of Springtime’. Robert Marsham FRS (1708-1797). ©The Trustees of the British Museum

Once, my wife – who planted trees for a living – made an excursion to the church in Stratton Strawless (gravelly soil, poor crops, no straw) to pay homage to Marsham who had presented papers to the Royal Society on the cultivation of trees in poor soils. By chance, this was where a favourite piece of Norwich stained glass (the subject of my first blog post [2]) is also situated, so we could both pay homage.

Marsham shared this interest in botany and climate with his friend Benjamin Stillingfleet [3], born in Wood Norton, tutor to William Windham (1702-71) of Felbrigg Hall. When attending a women’s literary discussion group in London it was said that Stillingfleet was too poor to wear the black silk stockings of formal dress so came instead in his everyday blue worsted stockings [3]. As a consequence, the literary group started in the 1750s by Elizabeth Montagu, Elizabeth Vesey and friends, became known as the Bluestocking Society [4] – the word now a reminder of women who value a life of the mind (despite satirical attempts to undermine them).

‘Breaking up of the Blue Stocking Club’ by Rowlandson

Stillingfleet may have been the first in this country to use the classification system of the Swede, Carl Linnaeus [5]. The Linnean system was a hierarchical one in which organisms were divided between the Animal and Plant Kingdom and then filtered – according to similarities or differences in the structure of their sexual parts – through increasingly finer family groupings of class, order, genus, species, until the two names of genus and species were sufficient to identify any plant. For example, the fine structure of Bellis perennis allows the observer to differentiate between the common daisy and all other daisies. Stillingfleet’s friend and neighbour in London, the apothecary William Hudson, was another early adopter of the Linnean system in Flora Anglica (1762) [6]. However, in his foreword, Norwich-born Sir James Edward Smith makes it clear that this book was “composed under the auspices and advice of Benjamin Stillingfleet” [6].

Benjamin Stillingfleet of Wood Norton, Norfolk (1702-1771) by Johann Zoffany

James Edward Smith is a major figure in the intellectual life of this city but he has already had a post of his own [7] so, in brief: Norwich-born Smith persuaded his wealthy father to provide 1000 guineas for him to buy Linnaeus’s library and collection of dried plants. Smith Junior used this collection to start the Linnean Society of London, of which he was President, but in 1797 he retreated to Surrey Street in Norwich, bringing the collection with him. Scholars from around the world travelled to Norwich to see Linnaeus’s collection of ‘type specimens’ – permanent references for each named species. Sir James Edward Smith FRS became the foremost British botanist of his day, producing numerous scholarly works such as Flora Brittanica, The English Flora and the 36-volume English Botany.

Former home of the Linnean Collection, JE Smith’s house 29 Surrey Street Norwich (at right)

In his Letters, Smith acknowledged ‘a small circle of experienced observers at Norwich’ for propagating the principles of theoretical botany [8,9]. This, he thought, could be attributed to the love and cultivation of flowers imported by Protestant refugees from the Low Countries – our famous ‘Strangers’ [9].

As dispensers of herbal medicines, apothecaries had professional reasons for identifying plants. Hugh Rose (1707-1792), an apothecary of Tombland, collected the Linnean names of edible plants. Together with Reverend Henry Bryant, Rose produced a translation of Linnaeus’s Elements of Botany to which they added an appendix on Norfolk and Suffolk plants [9]. Rose and Bryant weren’t isolated figures but part of The Norwich Botanical Society, founded ca. 1760 [10].

An apothecary. Wikimedia Commons

The surgeon-apothecary, John Pitchford, came to Norwich in 1769 where he was “last of a school of botanists of this city, among whom the writings and merits of Linnaeus were perhaps more early, or at least philosophically studied, than in any other part of Great Britain”[8]. Sir James Edward Smith recorded that this Norwich and Norfolk circle was comprised of Rose, Bryant, Pitchford and Stillingfleet (supplemented by correspondence with Londoner Hudson) and that these were “the founders of Linnean botany in England [9].”

Though not a Norwich man, nor a botanist primarily interested in flowering plants, the wealthy Yarmouth banker, Dawson Turner FRS (1775-1855), was to have a profound influence on this Norwich circle [11].

Gurney and Turner’s Yarmouth Bank – later Barclays Bank – on Hall Quay, Gt Yarmouth

Dawson Turner was a good friend of James Edward Smith and succeeded him as President of the Linnean Society [5]. Turner had wide-ranging interests and Gudrun Richardson’s essay, ‘A Norfolk Network within the Royal Society,’ acknowledges his central importance in maintaining a web of Norfolk scientists [8]. Of course, Turner’s network stretched beyond Norfolk: one of his correspondents was the eminent Welsh botanist Lewis Weston Dillwyn FRS (1778-1855), owner of the Cambrian Pottery [12] and co-author of ‘The Botanist’s Guide through England and Wales’.

Swansea creamware botanical plate ‘Sweet pea’. Dillwyn & Co ca 1815

Turner’s wife Mary was also an ardent botanist although 11 children hindered her full participation. She was a skilled artist and made engravings of drawings from her husband’s collection.

JE Smith as a child. Engraved by Mrs Mary Dawson Turner from a drawing by T Worlidge. Courtesy Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons CCBY

A year after Mary’s death, Dawson Turner married the widow Rosamund Duff – a marriage deplored by his children. Turner forbade Rosamund’s sister to visit his house but, after finding her hiding in a kitchen cupboard, discovered she had been secreted about the house for a fortnight [13]. Uproar ensued.

Dawson Turner 1837, age 52. Artist unknown

The friendship between Dawson Turner and JE Smith was close: no doubt some wry Victorian humour was being conveyed when Smith wrote to thank Turner for the loan of a rhinoceros horn that was being returned by Norwich School artist, John Sell Cotman [8]. The blue plaque outside Bank House commemorates polymath Turner solely as a ‘Distinguished Great Yarmouth Art Collector’. Indeed, Turner may now be best remembered as person who employed Cotman as painting master to his family and who sponsored Cotman’s painting expedition that produced ‘Architectural Antiquities of Normandy’.

‘Normandy Harbour’ by John Sell Cotman. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM: 1951.235.267

Turner studied non-flowering plants like algae, mosses, ferns and fungi that reproduce by spores instead of seeds. A young botanist born in Magdalen Street, Norwich – William Jackson Hooker – discovered a rare moss in a fir plantation in nearby Sprowston so Smith introduced him to Dawson Turner [14] who was to employ Hooker’s excellent draughtsmanship to illustrate his Natural History of Fuci (brown seaweed) [5]. Hooker became Director of the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew from 1840 to 1865. He married Turner’s daughter Maria, and their son – Joseph Dalton Hooker – succeeded his father as Director of Kew (1865-1885) [7].

JD Hooker was Charles Darwin’s closest friend and confidant. Another of Darwin’s inner circle was Professor John Stevens Henslow who had been his tutor at Cambridge and became his life-long mentor, helping Darwin gain his place on HMS Beagle. Completing the triangle, Hooker was to marry Henslow’s daughter [15].

JD Hooker ca 1852, by WE Kilburn (Wikipedia. Public domain)

Twenty years after the Beagle (1836), Darwin was still painstakingly amassing evidence to support his big idea that organisms born with natural variations, which allow them to adapt to environmental change, are more likely to survive and pass on those successful traits to offspring. That is, species are not fixed but evolve. Various arguments have been put forward for Darwin’s tardiness: a parasitic disease contracted in South America; hypochondria; bereavement; religious scruple; or a determination to accumulate an irrefutable weight of evidence to support such a revolutionary idea.

Charles Darwin 1809-1882

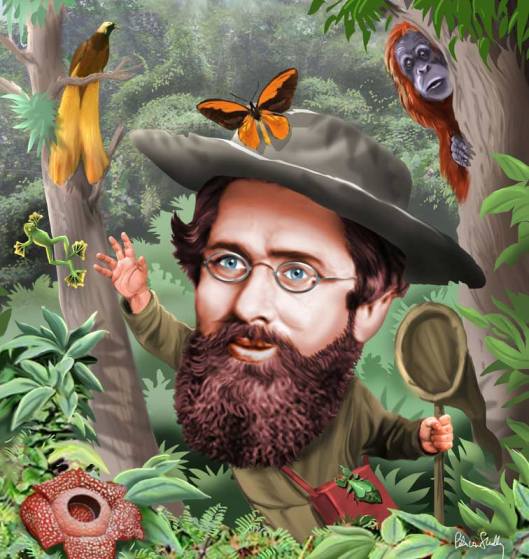

However, the Welsh naturalist and explorer, Alfred Russel Wallace, independently came up with the idea of natural selection and, after he sent a summary to Charles Darwin, Darwin’s friends rallied round to ensure that he wasn’t scooped. It was JD Hooker who, with geologist Charles Lyell, arranged the joint publication of Darwin’s and Wallace’s papers [15].

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913). Is that a Darwin-like ape in the background? ©Peter Von Sholly

According to the Theory of Evolution organisms continue to evolve over time and, if this were true, all species that had ever lived could not have been minted once-and-for-all on a single day (Day Three of Creation for plants and Day Six for animals). This formed a clear challenge to religious orthodoxy, prompting the historic Evolution Debate in Oxford, 1860 [16]. Bishop Wilberforce of Oxford (named ‘Soapy Sam’ after Disraeli called his manner, “unctuous, oleaginous, saponaceous”) is said to have asked ‘Darwin’s bulldog’ TH Huxley if he was descended from a monkey on his grandfather’s or his grandmother’s side. Huxley replied that he wouldn’t be ashamed to have a monkey as an ancestor but would be ashamed to be related to a man who used his great gifts to obscure the truth. But in his letter to Darwin, Hooker claims to have landed the more significant punches [16].

On an early Spring morning I followed the Hooker Trail in Halesworth, Suffolk. From the small museum I walked through the town, past Hooker House, ending up at the Memorial Garden & Arboretum. There I found labels bearing the names of some of the plants named after the Hookers: Inula hookeri, Crinodendrum hookerianum, Sarcococca hookeriana, Deutzia hookeriana and Rosa ‘Josephine Hooker’ (JD Hooker’s grand-daughter who lived to 103). On my return down the high street I bought the essential Hooker tea towel.

Not all of the Norwich circle were high-born or wealthy for although John Lindley (1799-1865) was educated at Norwich School his father was a nurseryman from nearby Catton [17].

John Lindley in 1848. From, The Makers of British Botany (1913). Wikipedia

Hooker introduced Lindley to the President of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks, who employed him in his herbarium. This was the start of Lindley’s ascent. Although he hadn’t been to university Lindley became Professor of Botany in non-denominational University College where he insisted on teaching Botany as an independent subject, not as an adjunct to Medicine. And as Secretary of the Royal Horticultural Society he revived its fortunes; if you have visited the RHS headquarters in London you will have seen the Norwich man commemorated by the Lindley Library, the largest horticultural library in the world [18].

RHS Lindley Library London. (Credit: growing-underground.com)

Botanical research continues in Norwich, home to the John Innes Centre [19].

The John Innes Centre, Norwich. Courtesy of John Innes Centre

In 2000 this world-leading centre for plant science research took part in decoding, for the first time, a plant’s genetic blueprint (its genome). Now, the genomes of well over 200 flowering plants have been published worldwide making it possible to line up these DNA sequences, to see the extent of their relationship, and to estimate how far back in time they diverged – the molecular counterpart of Darwin’s Tree of Life.

© 2019 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- Susanna Wade-Martins (2015). The Conservation Movement in Norfolk. Pub: The Boydell Press.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2015/12/19/norfolks-stained-glass-angels/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_Stillingfleet

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Stockings_Society

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004). Pub: OUP.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Hudson_(botanist)

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/01/15/when-norwich-was-the-centre-of-the-world/

- Gudrun Richardson (2012). A Norfolk Network within the Royal Society. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. Vol. 56, pp. 27-39.

- James Edward Smith (1832). Memoir and correspondence of the late Sir James Edward Smith, edited by Lady Pleasance Reeve Smith. Vol 1, available online: https://archive.org/details/memoircorrespond02smit/page/474

- Paul A. Elliot (2010). Enlightenment, Modernity and Science. Pub: I.B.Tauris, London.

- Anne Secord (2007). Nature’s Treasures: Dawson Turner’s Botanical Collections. In, Dawson Turner: A Norfolk Antiquary and his Remarkable Family, pp43-66. Ed., Nigel Goodman. Pub: Phillimore, Chichester.

- https://www.swansea.ac.uk/crew/research-projects/dillwyn/

- Papers of the Turner, Palgrave and Barker families. Hudson Gurney (1775-1864). Norfolk Record Office. NROCAT 2847/N2/4/1-17.

- https://archive.org/stream/b21726115_0005/b21726115_0005_djvu.txt

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Dalton_Hooker

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1860_Oxford_evolution_debate

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Lindley

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lindley_Library

- https://www.jic.ac.uk/

Thanks to: Dr Tony Irwin, Research Associate, Norfolk Museums Service; Dr Anne Secord, Editor, The Darwin Correspondence Project, Cambridge University Library; Sarah Wilmot, Archivist, John Innes Historical Collections; Professor John Snape, former Head of Crop Genetics, John Innes Centre, Norwich; and the staff of Halesworth and District Museum.

Great stuff….thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you Paul.

LikeLike

My goodness what a network, and what a fabulous post, Reggie! Thank you. Did you go into Hooker House while on the trail in Halesworth. My husband uses the dentist based there and the last time I went in the building there were a number of displays of Hooker memorabilia in the hall.

LikeLike

I did call into Hooker’s house, Clare. The displays on the wall were very good but I felt an interloper and didn’t photograph them. The Hooker Trail is a pleasant excuse to see this pretty town.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The United Friars: Charity and Enquiry in the Age of Reason | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH