In 1775, Reverend James Woodforde came to Weston Longville, a small village north of Norwich, and remained as rector until his death in 1803. During this time he kept a diary of his life as a country parson but city-dwellers will find it intriguing for his forays into late eighteenth century Norwich.

“… we both agreed it was the finest City in England by far …”

On first visiting Norwich with a friend (1775)

I am following a fascinating booklet on Woodforde’s walks around Norwich by the Parson Woodforde Society [1]. Much has changed across the two hundred and forty five years between his time and ours: World War II bombing raids; the Industrial Revolution; slum clearance; and fitting a medieval city around the motor car. These things changed the city but what is striking is how much of Woodforde’s Norwich still glimmers through. We start at the Marketplace but there is so much to see that we won’t wander far.

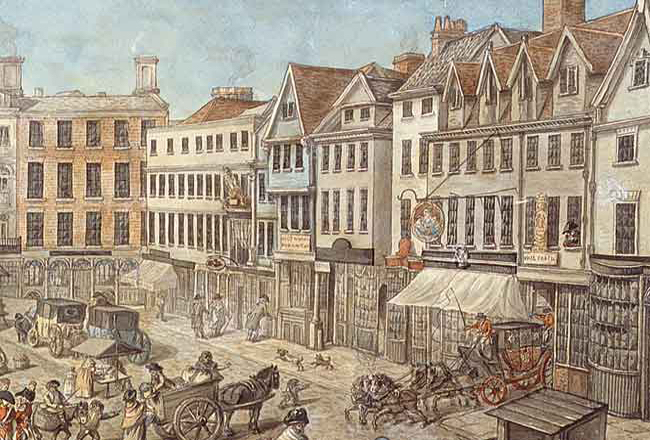

The Market established by the Normans, which supplanted the Anglo-Scandinavian trading place in Tombland, has been the thriving hub of the city for almost a thousand years. Here it is in Cotman’s illustration of 1807, not long after Woodforde’s death.

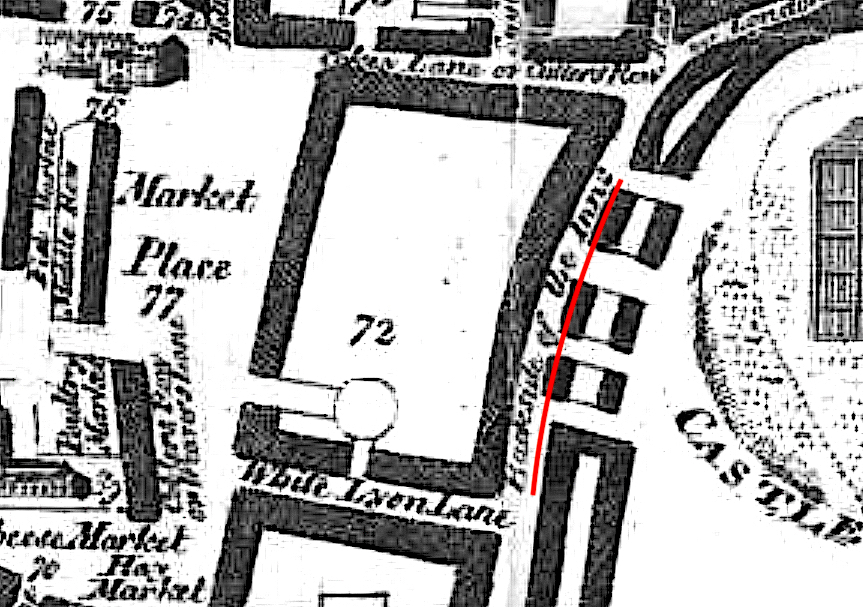

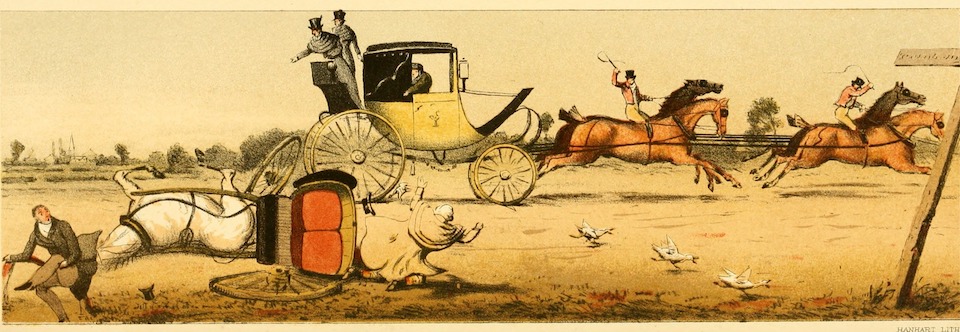

Looking back from the south end, Robert Dighton’s illustration (below) just manages to catch the medieval Guildhall (red arrow), obscured by the tall buildings to the rear of the marketplace. Centre left, the gap between the buildings is Dove Lane but note the absence of a major north exit from the far right corner. To the right of the market is a range of inns and from one of them the London coach is exiting at speed (yellow arrow).

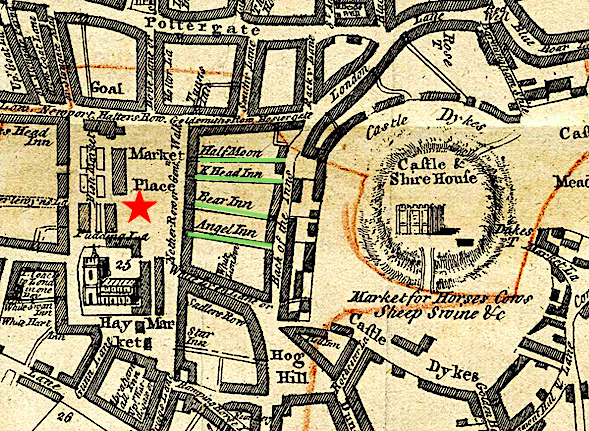

In acknowledgment of the stables behind the coaching inns, Blomefield’s map of 1741 names the lane to the rear as Backside of the Inns.

But by 1766 Samuel King had dignified it as Back of the Inns – the name still used today. He also lists the inns along the east side.

There were inns all around the marketplace but the ones on the east side are given as The Half Moon, The King’s Head, The Bear Inn and The Angel Inn. From The Angel, Parson Woodforde is known to have caught the coach, which he refers to as the ‘London Machine’ or ‘the machine’ [1].

In 1775, Woodforde’s journeyed from London to Norwich, by post chaise and four (horses): ‘109 miles, and the best of roads I have ever travelled.’ Arriving after ten o’clock at night he found the city gates shut (presumably St Stephen’s Gate), reminding us that the medieval defences were still largely intact at that time. In a telling metaphor for the changes inflicted upon a medieval city by the Victorian age, the stretch of city wall to the north of St Stephen’s Gate was to be used as hardcore for the new Prince of Wales Road. Built in the 1860s, this was intended as a grand approach to connect the new Thorpe railway station with the city centre. The advent of steam was to affect other routes to the city’s markets.

Small changes to the Marketplace accrued after Woodforde died. In 1840, when Queen Victoria married, the fifteenth century Angel Inn was patriotically renamed The Royal. In 1899 it would be demolished and replaced with a fashionable arcade designed by George Skipper [2]. Moulded in marble-like Carrara Ware by Doulton’s WJ Neatby, the figure above the Back of the Inns entrance commemorates the original Angel Inn. As the Royal Inn was disappearing (1896-7), Edward Boardman was building a new Royal Hotel on Agricultural Hall Plain, close to various livestock markets around the Castle, and closer to the railway station.

The fronts of these inns were separated from the Norman Great Market by what appears on King’s Plan of 1766 as ‘Nether Row or Gentleman’s Walk’. ‘Nether’ refers to a lower row of market stalls arranged outside the inns but as early as 1681, Thomas Baskerville had written about ‘a fair walk before the prime inns and houses of the market-place…called gentlemen’s walk or walking place…kept clear for the purposes from the encumbrances of stalls, tradesman and their goods’. Evidently, the walkway outside the inns had become an acceptable place for members of an increasingly polite and enlightened society to promenade, separated from the hurly-burly of the market. An early photograph from 1854 shows The Walk as a paved boulevard set apart from the market by a line of posts [3].

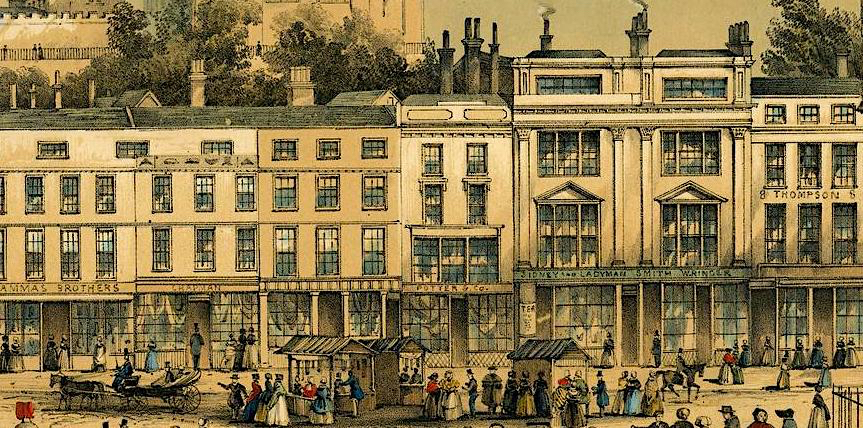

Newman’s lithograph provides a sense of the fashionable shops along the east side of the marketplace – an early shopping parade.

Woodforde is known to have visited John Toll’s draper’s shop in the Marketplace. He paid seven shillings and sixpence for a pair of cotton stockings for his niece Anna Maria (Nancy) who was his housekeeper and companion [4]. At the shop of Mr Tandy (a ‘Chymist and a Druggist’) he spent three shillings on an ounce of ‘Rhubarb’, presumably tincture of rhubarb, taken for digestive complaints. For thruppence he also purchased Goulard’s Extract, used for inflammation of the skin, although this was later discontinued as it was found to cause lead poisoning.

Although Parson Woodforde drank coffee at The Angel he did not often stay there, preferring to lodge at The King’s Head. It was from here that the Norwich mail coach departed for Yarmouth [1]. And from 1802, two mail coaches left here daily for London, one via Ipswich and one via Newmarket [5].

Below, Newman’s painting of 1850 shows key changes to the Marketplace as Woodforde would have known it.

In Woodforde’s time there was no wide street exiting the square at the north-east corner but, in 1832, Exchange Street was cut through, connecting the market to St Andrew’s Street then over the newly erected Duke’s Palace Bridge and on towards North Norfolk [6]. On the painting above, the purple arrow points to something that would have rocked Parson Woodforde’s world.

In 1812, Alderman Jonathan Davey – Baptist Radical of Eaton Hall – announced in a council meeting that he would put a hole in the king’s head. These apparently seditious words were taken sufficiently seriously for a guard to be placed upon his house but what he actually intended was to put a hole in Gentleman’s Walk. He bought the King’s Head Hotel at auction, demolished it and in place of Woodforde’s preferred coaching inn built a shop-lined thoroughfare that connected those attending the livestock markets around the Castle with the Marketplace [7]. Along with Exchange Street, Davey Place is one of the rare post-medieval streets of Norwich.

The ‘Davey Steps’ connecting Davey Place to Castle Meadow provided a barrier to animals, although the stairway was not insurmountable. In April 1823: “A man who sold sand about the streets of Norwich drove his cart and pair of horses up the flight of ten steps, leading from Davey Place to the Castle ditches. The horses did it with much ease and without receiving any injury, to the astonishment of the spectators” [8].

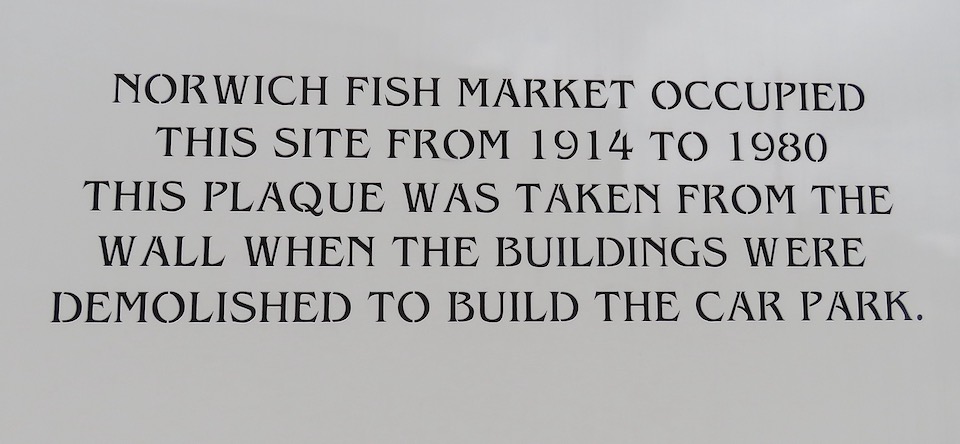

Running westward from the Guildhall, at the back of the market, was the fish market.

Here, Woodforde bought soles from Mr Beale, which were sometimes less than fresh [1]. In the days before refrigeration he would take home oysters from the market, although he could also buy them from ‘an old man of Reepham’ [4]. The insanitary Fish Market was replaced in 1860 by a Neoclassical building approximately where the Memorial Gardens are today. This building is at centre of the photograph below. To the right, the building with roof lucams is The Fishmonger’s Arms, a Youngs, Crawshay and Youngs house.

All the old buildings at the back of the market were cleared as part of the construction of City Hall and the Memorial Gardens (1938).

In 1914 the Fish Market was transferred out of the Victorian building and re-sited to Mountergate.

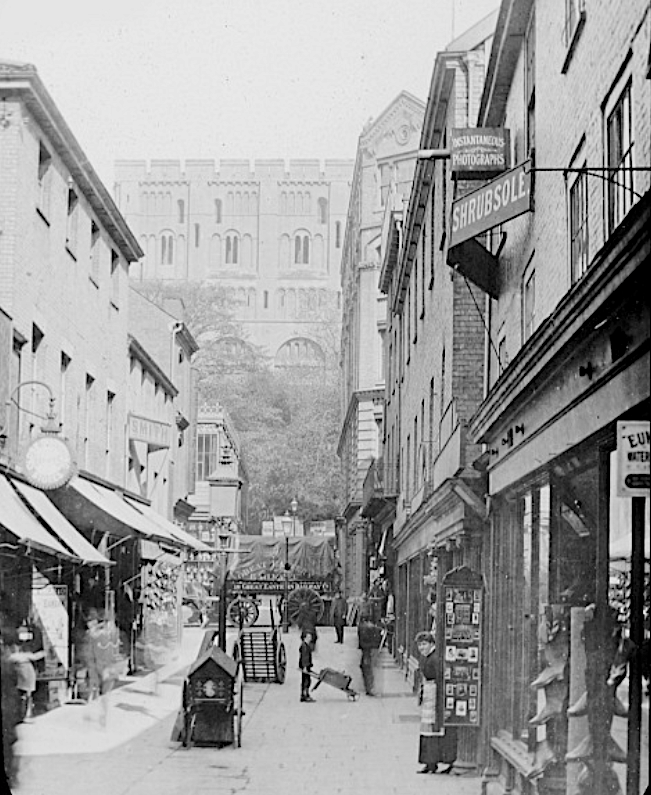

As the Back of the Inns followed the curve of Castle Meadow it flowed into medieval London Lane. This route was narrow and far from ideal. The opening of Norwich (later, Norwich Thorpe) railway station in 1844 created demand for better access to and from the market and London Street was widened accordingly[6]. Most of the medieval buildings familiar to Woodforde were demolished. He would, though, have known this grand doorway from the house of John Bassingham, a goldsmith from Henry VIII’s time, now inserted into the Magistrate’s Entrance of the Guildhall [10].

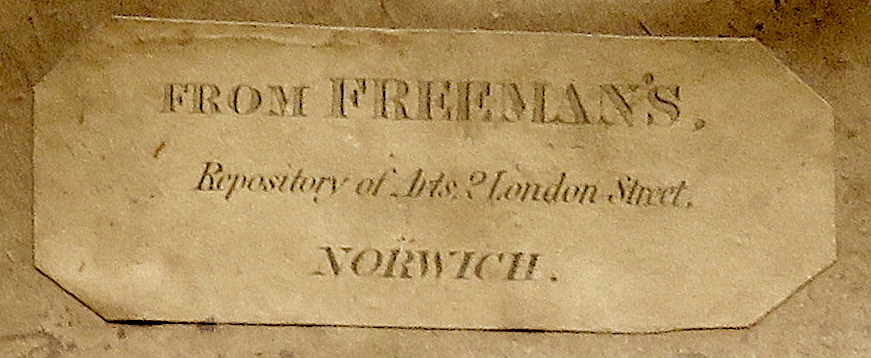

The premises of Edward Freeman were in Back of the Inns. We previously encountered this family of cabinet makers when looking at a framed medallion of Amelia Opie [11]. Freemans made high quality picture frames and furniture for country houses like Felbrigg and Blickling Halls but Woodforde’s requirements were more humble: he paid a guinea deposit for two mahogany chests of drawers and half a dozen ash kitchen chairs.

Cockey Lane was at the Guildhall end of London Street, just around the corner from Back of the Inns, and this is where Woodforde visited his upholsterer, James Sudbury. In 1793, two of Sudbury’s workmen – Abraham Seely and Isaac Warren – are claimed to have carried a ‘large New Mohogany Cellarett’ and a sideboard ‘on the Men’s shoulders all the way’; that is, nine miles to Weston Longville [12]. For this Herculean feat Woodforde fed and watered the men and gave them a shilling tip but I can’t help wondering if Sudbury’s cart was hidden down the lane.

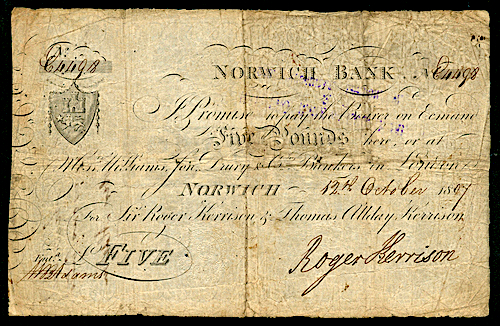

Kerrison’s Norwich Bank in the Back of the Inns was where Woodforde brought tithe money collected on behalf of his friend Henry Bathurst (later, Bishop of Norwich) who was then non-resident parson of a neighbouring parish [4]. Woodforde would exchange bills and cash for a banknote that he sent by post to his friend in Oxford. On one occasion he celebrated his good deed by dining at the King’s Head on a mutton chop and a bottle of wine. Five years after Woodforde’s death, Sir Roger Kerrison was to die in an apoplectic fit after which his bank failed, unable to pay the Government the money he had collected as Receiver-General [13].

In 1793, Parson Woodforde banked £2-12s-0d, collected at Weston Longville for emigré French clergy. These refugees from the French Revolution joined a line of French Protestants who had been finding sanctuary here since the sixteenth century [14]. Just south of the Marketplace, in the smaller Haymarket (and Cheese Market), Woodforde had his watchspring repaired by master watch-maker Peter Amyot, a descendant of French Huguenots [1]. In his diary, Woodforde also mentions other descendants of immigrants: like James Rump, grocer and tallow chandler (whose name had been anglicised from Rumpf [14]); Elisha de Hague, attorney; and the influential Martineau family, underlining the contribution that newcomers made to this city’s commerce.

©Reggie Unthank 2020

Sources

- ‘Walks Around James Woodforde’s Norwich’ (2008). Published by The Parson Woodforde Society https://www.parsonwoodforde.org.uk/. The booklet is still available from editor@parsonwoodforde.org.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/03/12/the-art-nouveau-roots-of-skippers-royal-arcade/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norwich_Market

- https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.227134/2015.227134.The-Diary_djvu.txt

- http://www.norwich-pubs-breweries.co.uk/norwich_pubs_past/norwich_pubs_past.shtm#

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://www.eveningnews24.co.uk/views/derek-james/street-has-its-place-in-city-history-1-1520880

- In, Norfolk Annals, edited by Charles Mackie. Available online https://www.gutenberg.org/files/34439/34439-h/34439-h.htm

- Michael Loveday (2011). The Norwich Knowledge. Pub: Michael Loveday ISBN 978-0-9570883-0-6

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/01/15/the-norwich-coat-of-arms/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2020/01/15/behind-mrs-opies-medallion/

- https://bifmo.history.ac.uk/entry/sudbury-james-sen-1743b-1814d

- Roger Ryan (2004) Banking and Insurance. In, ‘Norwich since 1550’. Eds Carole Rawcliffe and Richard Wilson. Pub: Hambledon and London.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/08/15/going-dutch-the-norwich-strangers/

Thanks to Alan Theobald for introducing me to the booklet, ‘Walks Around James Woodforde’s Norwich’. Copies are available from editor@parsonwoodforde.org. I am grateful to Martin Brayne of the Parson Woodforde Society for his assistance. To learn more about Parson Woodforde and the society in which he lived, visit https://www.parsonwoodforde.org.uk. I am grateful to Clare Everitt for permission to use images from the wonderful archive of local photographs: Picture Norfolk. Thanks, also, to Jonathan Plunkett for allowing access to his father’s photographs of Norwich and Norfolk: www.georgeplunkett.co.uk

Parson Woodforde’s Diaries are a favourite of mine so learning in more detail about the man himself moving around our fine city, is a treat.

Thanks

LikeLike

Thank you Sue. I had also read some of the diary and was surprised to find how much of his Norwich could (just about) still be seen.

LikeLike

Another fine walk in Norwich. One way of keeping my memories of Norwich alive! Thank you, Reggie,

Eva.

LikeLike

Pleased you have fond memories of the city. Reggie

LikeLike

Well done Reggie. What an interesting article. It is surprising how often the Parson travelled out of the County.

LikeLike

Yes, he was a traveller and by his own accounts he lived very well. Reggie

LikeLike

Hi,

Reggie, you may remember I gave you some information on the Minns Bros Carvers who worked for a time at Gunton Bros Brickworks in Costessey. I also have an interest in Parson Woodforde’s Diaries, as My Grt Grt Grt Grandfather John Mann was a Tenant Farmer and lived in Weston Longville. I think he was a Church Warden to Parson Woodforde & also Overseer For The Poor. He and his Wife are buried inside the Church in the aisle next to the pews that they used; I think it cost a guinea each to be buried inside the Church, Since the 1700s, the family have not moved far, Weston Longville/Ringland/Taverham/Costessey.

Regards Peter

LikeLike

How fascinating to hear of connections with Parson Woodforde. I’m envious of your family’s long connections with this area, Peter.

LikeLike

Parson Woodforde left a wonderful picture of life in his time but I had forgotten how much Norwich figures in his Diaries. Of the views of the Marketplace I particularly like that of the north end between Dove Street and Exchange Street – ‘a building shabbily treated’ Andrew Stephenson wrote. It is a little better now than in the 1940’s when Arnold Kent photographed it but still nowhere near what it could be. Those of my generation will remember Princes restaurant there for afternoon tea.

Keep up the good work

Don Watson

LikeLike

Thanks for sending me back to Kent and Stephenson’s book, Don. They show photographs of Norwich immediately after the war and it’s shameful to read about the destruction of Georgian windows in the Princes café. Each generation of shop owners demands a modern front and new signage but it’s still possible to spot these fine buildings by looking above the eyeline.

LikeLike

I especialy love this post at a time when we can look at the quiet streets and imagine…

LikeLike

It’s clear from the old maps that the bare bones of the city survive. I found the Cotman painting of the marketplace very evocative and shall try to find a decent print.

All best, Reggie

LikeLike

A fascinating article ,Thankyou Reggie .

LikeLike

Thank you for the kind feedback Liz

LikeLike

Wonderful stuff. Love how you find a new way to see the city each time. Daniel (Michigan ex-Norfolk, new WP account)

LikeLike

Hi Daniel, Woodforde is the ideal companion for a walk around the city. His diary is worth seeking out. Reggie

LikeLike

Once again, a brilliant article – I have a soft spot for the Parson! Thank you Reggie!

Haydn

LikeLike

Thank you Haydn. Yes, he comes across as likeable man and the diary gives great insight into his times. The accounts of his dinners are astounding by modern standards, with several meat dishes and even a pudding as the FIRST COURSE.

LikeLike

I do like Parson Woodforde! We lived in Somerset for a short while and we always drove past Castle Cary on the way back to Suffolk to visit my parents. I often thought of the Parson leaving his relatives there and travelling with his niece all the way to Weston. I really enjoyed this post, Reggie and am tempted to get the Woodforde walks booklet.

LikeLike

I would certainly recommend the Woodforde Walks booklet. It’s a great vehicle for accessing Norwich history and I’m contemplating another excursion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Parson Woodforde and the Learned Pig | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Norwich Department Stores | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

I am very grateful for these details. I always think of Mr Woodforde and his expensive stays at the Kings Head whenever I visit Norwich. Thank you for the pictures too.

LikeLike

Yes, Parson Woodforde is a most agreeable commentator on life in C18 Norfolk and Norwich. Whenever I walk down Davey Place I can’t help thinking that his favourite Kings Head was demolished in order to make way for this street.

LikeLike

Now that I know that about Davey Place, I shall do the same, I suspect.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Georgian Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The United Friars: Charity and Enquiry in the Age of Reason | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The Severe English Winter of 1794-1795 Began on Christmas Day: First-Hand Accounts | Jane Austen's World