Three years ago I wrote about the Norwich artist Catherine Maude Nichols [1] and was surprised to find that she was one of only three women who, like 360 of the city’s male worthies and businessmen, presumably paid to have their potted biography and photograph featured in a Norwich trade book published in 1910 [2]. This book – Citizens of No Mean City – was evidently opaque to the political mood for this was around the time that Margaret Jewson set up the Women’s Freedom League in the city (1909) [3] and Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) opened an office in London Street for the suffragette movement (1912). All of the featured men in the book would probably have been able to vote; admittedly, not all males could vote but women with the franchise were fewer still. They were not to gain parity with men until 1928.

The figure of Joan of Arc was a suitably militant emblem for an organisation that believed in action not words. She was brought to life on several occasions by the leading suffragette, Elsie Howey, riding a white charger.

CATHERINE MAUDE NICHOLS (Read her biography in [1]).

While Henry Cadman felt able to proudly declare his membership of the Gas-workers’ and General Labourers’ Union in his biography, Catherine Maude Nichols made no mention of her political affiliation. She was, however, known to have been active in the local branch of the National Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUMSS) set up in 1909 [3] and the name of ‘Miss Nichols’ (surely our Miss Nichols) appears in the first annual report of the WSPU in 1907, which records a contribution of £11 16s Od.

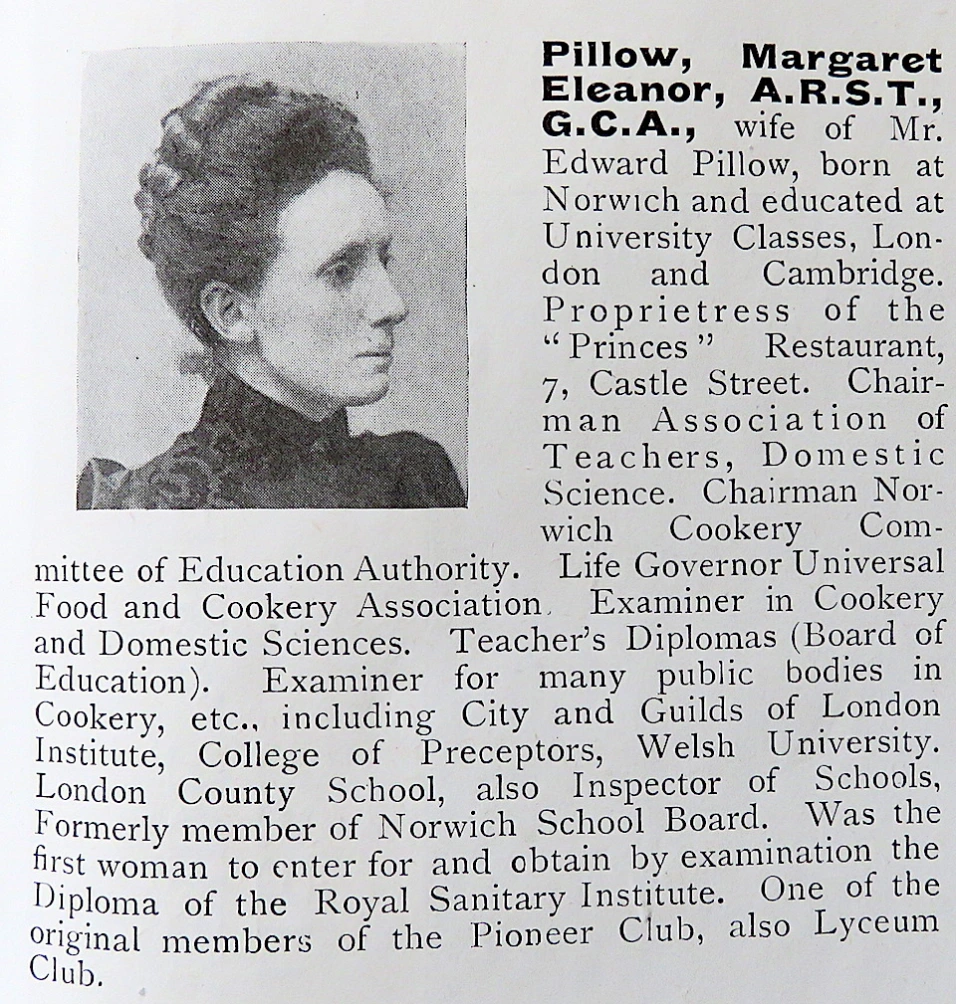

MARGARET PILLOW

The second of the Norwich women to have an entry in ‘Citizens of No Mean City’ [2] was Margaret Eleanor Pillow, a friend of Miss Nichols who had studied at Cambridge but at that time was not allowed to take her degree. She listed an impressive string of credentials, including the diploma she was allowed to take from the Royal Sanitary Institute that led to her becoming the first female sanitary inspector in the country. Margaret was a pioneer in a man’s world and there are clues to her political stance. As a founding member of the Pioneer Club and the Lyceum Club she would have been in an environment where women’s rights were fervently discussed. Members seem to have been non-militant suffragists, rather than suffragettes who believed in direct action (‘Deeds not Words’), but her sympathies for the more militant wing can be inferred from the fact that her wedding reception was held at the home of Mrs Pankhurst – luminary of the suffragette movement [3].

MIRIAM PRATT

In 1912 the WSPU, spearheaded by Emmeline Pankhurst, opened its Norwich office at 52 London Street. The keys were held by Miriam Pratt who sold The Suffragette from the corner of Gentleman’s Walk and London Street. Miriam (1890-1975) had moved from Surrey, aged eight, to live in Norwich with her aunt Harriet and her husband Police Sergeant William Ward. This was in Grove Avenue, not far off the junction between Ipswich Road and Newmarket Road [3]. The name of Miriam A. Pratt , age 12, appears on the list of pupils at Duke Street Elementary, the former board school in the city centre. By spring 1913 Miriam had become a teacher at St Paul’s School and was living at Turner Road on the other side of the city, off Dereham Road. She was a member of the St Peter Mancroft Dramatic Society and there are several mentions in local papers of appearances, including a piano duet at a temperance meeting with Miss Stribling [4] and a part in ‘Three Irish Plays’ in Mr Orams’ garden, where the enjoyment of a ‘scanty’ audience was marred by a cold wind [5].

From 1912 to 1914, Emmeline Pankhurst’s daughter Christabel orchestrated a nationwide bombing and arson campaign [6]. Miriam became one of her unmarried ‘Young Hotbloods’ and in 1913 attempted to set fire to a house under construction on Storey’s Way on the outskirts of Cambridge, together with the Balfour Laboratory of Genetics in the centre of Cambridge. She and her companions left behind an unfortunately melodramatic trail of clues: suffragette leaflets were found at both sites; the prints of a woman’s boot had been left on a newly cemented floor at Storey’s Way; blood was detected on broken glass; and a woman’s gold watch was found beneath a broken window. Having read about the fire in a Norwich newspaper, Miriam’s uncle, the policeman, questioned Miriam who admitted the watch was hers – in fact, it was one he had given her – and that she had cut her finger when trying to remove putty with a pair of scissors. She was arrested within days and on the morning of 22nd May was taken into custody. Later that day she was bailed on a £200 surety by Dorothy Jewson and her brother. Dorothy was to become the first female MP in East Anglia [3].

On bail, Miriam was unable to return to teaching but was employed on a temporary basis in the office of the Norwich Education Committee [7]. On the 18th of July, she attended a meeting of over 2,000 people in Norwich marketplace demonstrating against the so-called `Cat and Mouse Act’ of 1913 in which prisoners weakened by force-feeding were temporarily discharged until they were strong enough to be returned to prison to be force-fed once more[3].

She was tried at Cambridge Assizes on Friday 14th October 1913. The Diss Express reported that Miriam was ’a pleasant looking young woman, who was attired in a violet-coloured costume with hat to match, and wearing a large bunch of violets at her waist’ – a reference to the suffragette colours of Green, White and Violet: Give Women Votes. Miriam’s solicitor claimed the cut on her finger could not have been caused by broken glass. He asked her to approach the magistrates’ bench and, according to the Manchester Daily Citizen, ’the young girl laughed merrily … and showed each of them the wound.’ Despite her eloquent defence her uncle’s evidence – which he read ’under the stress of considerable emotion’ – proved damning and she was sentenced to 18 months’ hard labour. The policeman, torn between duty and love for his niece, was later to become Honorary Secretary of the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement [3].

The attack on the Balfour Biological Laboratory for Women seems like an own goal for, at a time when barriers were erected to women attending lectures and practicals, and few actually sat the Tripos exams, the laboratory had been set up specifically for young women by the Vice-Principal of Newnham, Eleanor Sidgwick and staffed by women who were, perforce, not members of university departments [8]. The rationale for the arson appears to have been that the suffragettes were drawing attention to the futility of women studying for degrees they would not be allowed to receive.

One of the assistants in the Balfour Laboratory was Anna Bateson whose brother William (1861-1926) coined the word ’genetics’ to describe the study of inheritance. The groundwork had been laid by the Austrian monk Gregor Mendel (1822-1884) who cross-pollinated different varieties of purebred pea plants and carefully recorded how characteristics like height or the wrinkling of pea seed were inherited (or not) by the offspring. Mendel’s work lay dormant until 1900 when it was rediscovered by three European scientists. William Bateson brought the discipline into the twentieth century with experiments in genetics pursued in a Cambridge laboratory staffed by his wife, sister and female students from Newnham. In 1910 Bateson was made the first director of the John Innes Horticultural Institution in Merton Park, Surrey. The John Innes moved to Bayfordbury in Hertfordshire in 1950 then moved again in 1967 to its present site on the outskirts of Norwich where it adds lustre to the Norwich Science Park.

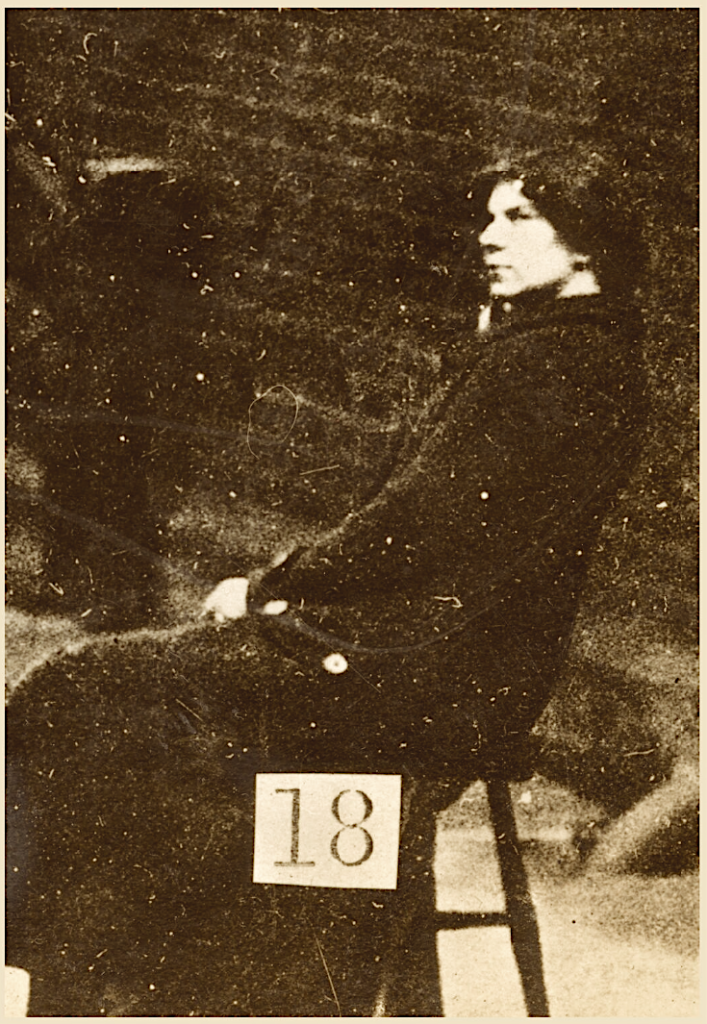

In Holloway, Miriam went on hunger strike and was force-fed. Some time that week she was captured by a surveillance camera secreted by Scotland Yard in a van parked in the exercise yard, her photograph intended to identify her at demonstrations.

© Museum of London

Miriam’s treatment seems to have weakened her heart; it left her in a critical condition and she was released under the terms of the Cat and Mouse Act against which she had demonstrated. She did not return to prison.

On the 24th October 1913 the nation’s local newspapers reported the ’disgraceful behaviour’ of suffragettes who, the previous Sunday, had interrupted services in London, Birmingham and Norwich. In Norwich Cathedral they are reported to have started a ‘chant’ but, as explained in The Suffragette, the intervention was more subtle than unruly. The group of suffragettes were sitting behind the canopied stall containing Mr Justice Bray who had handed down the harsh sentence to Miriam. Their ‘outrage’ consisted of an amendment to the daily prayer: ’O God, the Creator and Preserver of all Mankind, we humbly beseech thee for all sorts of conditions of men …’. When the cleric reached the words ’for all conditions of men’, where the names of those deserving of prayer could be inserted, the suffragettes stood up and sang in chorus, ’Lord, save Miriam Pratt and all who are tortured in prison for conscience’s sake.’ They stayed quiet for the remainder of the service and were not removed.

GRACE MARCON

Grace Marcon (b.1899) was the daughter of Canon Walter Hubert Marcon of Edgefield, North Norfolk. She raised funds for The Suffragette and attended WSPU meetings in Tombland – the ancient Anglo-Scandinavian marketplace outside Norwich Cathedral [9]. In 1913 and 1914 she was arrested three times for her direct action in London. On the third occasion she was sentenced to six months in Holloway for damaging five paintings in the National Gallery, including one by each of the brothers Gentile and Giovanni Bellini.

In targeting a famous painting, Grace Marcon was in the company of suffragettes who, between March and July 1918, emulated Mary Raleigh Richardson’s famous attack on the Rokeby Venus in the National Gallery by attacking 14 others. She produced a meat cleaver and before she could be stopped by the guards managed to slash the nude with, in her words, ’several lovely shots’. In consequence some museums would only allow entry to women who had a letter from, or were accompanied by, a gentleman who would vouch for them [10].

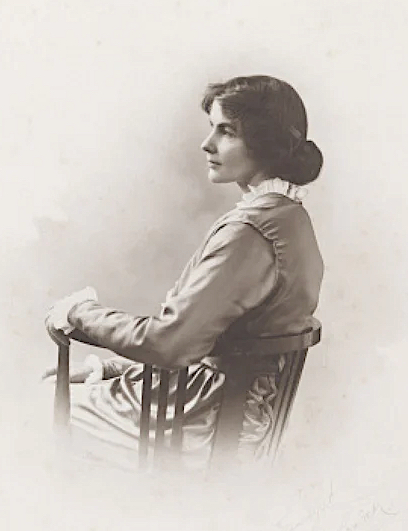

During her hunger strike Grace became delirious and felt that her hair was like red hot wires in her head; the surveillance photograph captures her before she cut off her hair.

The first time she was arrested she was bound over, not jailed. For her third arrest she used the nom de guerre, Frieda Graham, with the possible intention of saving her family embarrassment [11].

A street in Edgefield NR24 2RX is named after Grace’s father who was the local rector for over 60 years. He is commemorated in his church of Saints Peter and Paul, Edgefield, by John Hayward’s stained glass depicting him as a cycling parson [12].

VIOLET AITKEN

Violet Aitken, who lived to be 101 (1886-1987), was the daughter of William Aitken who became Canon of Norwich Cathedral in 1900 [13]. The WSPU’s campaign of window-breaking started on the first of March 1912 when hundreds of suffragettes launched themselves on London’s West End carrying concealed hammers and bags of stones [3]. Three days later there was another wave of attacks in which Violet was arrested for causing £100 of damage to the windows of Jay’s clothing shop (by appointment to Queen Alexandra) in Regent Street. Initially imprisoned in Holloway she was transferred to Winson Green, Birmingham, where she was force-fed after going on hunger strike.

Being fed by a nasal tube caused Violet to vomit continuously and she was released on medical grounds. She became editor of The Suffragette but thought of giving this up to make a living as a writer. She continued in post, however, following the funeral of Emily Davison (force-fed 49 times) who ran in front of King George V’s horse at the 1913 Derby. On Saturday June 14, 1913, Violet’s father entered these words in his red Asprey’s diary: ‘… very disappointing news from Violet that she is determined to go on with this wretched paper as she feels it would be like deserting the cause to leave them now.’ [14]

A year earlier, Canon Aitken had already confided his distress about Violet’s activities to his diary.

He wrote, ‘Violet … had again been arrested and this time for breaking plate glass windows. I am overwhelmed with shame and distress to think that a daughter of mine shd do anything so wicked and I can only throw the whole matter on Him who is the great burden bearer of His people. But my poor wife! It’s heartbreaking to think of her being exposed in her old age to this horror.’ [15]

Norwich did not avoid the wave of window smashing. In May 1913 the Dundee Evening Telegraph (Oh the randomness of newspaper searches) reported damage to a large new plate glass window belonging to Buntings the drapers in Rampant Horse Street, now the site of Marks and Spencer. Using a diamond, ‘Votes for Women’ had been scratched in the window together with three broad arrows relating to the imprisonment of WSPU activists. The window was smashed [3], its replacement estimated at £1000.

Ten days later the Diss Express reported that the glass slashers had gone on the rampage through Norwich, using a diamond(s) to make shapeless marks on what appears to have been most of the shop windows in the city centre. The main shopping parade along Haymarket and Gentleman’s Walk was affected; ‘even the bye-streets’ didn’t escape, including Prince of Wales Road, St Giles Street and ‘practically every shop in Dove Street’. Castle Street was also targeted including, rather curiously, Prince’s Tea and Luncheon Rooms belonging to suffragist Margaret Pillow.

CAPRINA FAHEY

Caprina Fahey came to local attention when Museum Trainee Andrew Bowen of the Norfolk Museums Service put out a call for further information about this suffragette who had died in 1959 in Hainford, a village just north of Norwich [16, 21]. One of her middle names gives the clue to her birthplace for she was born (1883) Charlotte Emily Caprina Gilbert on the island of Capri, the daughter of Alice Jane Gilbert and Alfred Gilbert – first cousins who married the day they eloped to Paris in 1876 [17].

Caprina’s father studied under the sculptor Sir Joseph Boehm and from the late 1880s to the mid-1890s achieved fame with major commissions such as the statue of Eros in Piccadilly Circus. Towards the end of this golden period Gilbert (now Sir Albert) overstretched himself, failed to complete work, fell out with the royal family and declared himself bankrupt [18].

As a young woman, Caprina trained as a masseuse before becoming a nurse and, later, a midwife. Her first husband was Alfred Fahey who was her father’s assistant and, according to the 1901 census, lived with them as a visitor with the occupation of ‘Artist (Painter Student)’. They married but he abandoned her with a child; she divorced Fahey, suing him for adultery and desertion and, unusually, winning custody of baby Dennis.

Caprina joined the WSPU in 1908, and in 1909 was imprisoned for a month for being part of a 27-strong deputation to the Houses of Parliament from the Women’s Parliament Meeting held in Caxton Hall. A year later she took part in the infamous Black Friday (18th November 1910). The WSPU supported the inadequate Conciliation Bill that offered the vote, not to all women but to about a million property-owners. But Prime Minister Asquith – no supporter of female emancipation – effectively blocked the bill when he decided to hold another election. In response to this betrayal, three hundred suffragettes marched from Caxton Hall to the Houses of Parliament where they were treated brutally. Police were redeployed from rougher areas like Whitechapel and there were reports that women were sexually molested. Caprina was sentenced to two weeks’ imprisonment for stone throwing.

Evidently, Caprina was an active campaigner for women’s suffrage and in 1910 was the WSPU organiser for the Middlesex Parliamentary Division [19]. A recently discovered copy of the programme for Emily Wilding Davison’s funeral confirms that Caprina was one the 11 group captains marshalling the various sections of the funeral procession [20]. Elsie Howey was part of the cortège, appearing as Joan of Arc mounted on her white horse.

During both terms in jail Caprina went on hunger strike for which the WSPU awarded her the Suffragette Medal with two bars ‘For Valour’. Despite her bravery Caprina’s father cut her out of his will, saying that Cappie was ‘a banner waver in a rotten Cause!!!!’ [17].

During the First World War, Caprina married Edward J J Knight. Sometime during the Second World War they moved to Rose Cottage in Hainford where she died on 26th October 1959. That same year, her husband presented Caprina’s suffragette medal to the Norwich Castle Museum [21].

The Colman family

The activities of the WSPU suffragettes drew most attention but others in Norwich – who either did not support direct action and/or wished to maintain contact with the Labour Party – also worked for the emancipation of women. These included: the Women’s Freedom League set up by Margaret Jewson in 1909; the Church League for Women’s Suffrage; the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement (of which Miriam Pratt’s uncle was the Hon Sec); and the Norwich branch of the National Women’s Suffrage Societies(NUWSS) [3].

Daughters of the Colman’s mustard dynasty, the Colman sisters, Ethel, Helen and Laura, were all active in Norwich politics. All three supported the call for female suffrage; they were not, however, members of the WSPU although they sent letters of support [3]. Following a meeting held in the Agricultural Hall in December 1909, when it was decided to set up the NUWSS, Ethel and Helen became Vice Presidents under Laura’s Presidency. And when Ethel became the Lord Mayor of Norwich in 1923 – the first female Lord Mayor in the country – she chose her sister Helen as official consort.

In January 1910 Helen L Willis – a prime mover in setting up the NUWSS – placed an advert in the Eastern Evening News to announce that the society was active in Norwich and that their office was open at 7 Brigg Street, near Rampant Horse Street. Her name also appears on headed paper of the Norwich Women’s Suffrage Society.

Edith’s home was in Southwell Lodge (now demolished), at the corner of Ipswich and Cecil Roads, where she lived with her parents. Her mother, Mary Esther Willis, was the sister of JJ Colman, manufacturer of English mustard, philanthropist and father of the three Colman sisters. Helen was therefore cousin of the three Colman suffragists who held the presidential posts in the local NUWSS while she was the Honorary Secretary [22].

In 1914, at the beginning of World War 1, the suffragette campaign was suspended and at the end of the war (1918) the vote was extended to women who were rate payers or who were married to one. Women and men were not able to vote under the same terms until 1928 but by this time women like Dorothy Jewson and Ethel Colman were playing a more active part in local and national politics.

Coda

While searching newspaper archives my eye was caught by an unexpected name ,’Senghenydd’, in the news clip following the one for Muriel Pratt’s sentencing in 1913.

I never met my paternal grandfather; I only know him by a handful of keywords of which Senghenydd is one. I recall relatives telling me that he led the mine rescue team from his own colliery to the mining village of Senghenydd in the neighbouring South Wales valley. In 1894, 290 men and boys had been killed in my grandfather’s pit but the number of fatalities in the Senghenydd explosion was far worse even than the 336 recorded by the Derry Journal for the death toll eventually reached 439.

©2022 Reggie Unthank

Thanks

I am grateful to Ruth Battersby Tooke, Andrew Bowen and Bethan Holdridge of the Norfolk Museums Service for information on Caprina Fahey. Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk, Rachel Ridealgh and Simon Knott helped me obtain photographs, as did Ben Craske of the Eastern Daily Press newspaper archives.

Sources

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/05/15/catherine-maude-nichols/

- Citizens of No Mean City (1910). Pub: Jarrold, Norwich.

- Gill Blanchard (2020). Struggle and Suffrage in Norwich. Pub: Pen & Sword Military

- Eastern Daily Press Monday 28 November 1910

- Norfolk News Saturday 20 July 1907

- Article by John Simkin https://spartacus-educational.com/Miriam_Pratt.htm

- Gill Blanchard (2022). Miriam Pratt (1880-1975) – A Norwich Suffragette. In, ‘Aspects of Norwich’ Pub: The Norwich Society.

- https://www.gen.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/2-balfour-lab.pdf

- https://www.norfolkfhs.org.uk/files/ancestor%20magazine/pdfs/2018/Norfolk_Ancestor_Vol_15_Pt_3_Sep_2018_cwr.pdf

- Diane Atkinson (2015). The Suffragettes in Pictures. Pub: The History Press.

- https://www.norfolkfhs.org.uk/files/ancestor%20magazine/pdfs/2018/Norfolk_Ancestor_Vol_15_Pt_3_Sep_2018_cwr.pdf

- http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/edgefield/edgefield.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Violet_Aitken

- Norfolk Record Office MC 2165/1/23, 976×4.

- Norfolk Record Office MC 2165/1/24, 976×4.

- https://www.norfolk.gov.uk/news/2018/01/public-appeal-success-in-filling-in-the-missing-pieces-of-norfolk-suffragettes-life

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caprina_Fahey

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Gilbert

- https://www.edp24.co.uk/lifestyle/heritage/call-for-public-s-help-to-piece-together-life-of-1116878

- https://womanandhersphere.com/2012/10/04/collecting-suffrage-emily-wilding-davisons-funeral-programme/comment-page-1/#comment-278316

- https://norfolkthreads.wordpress.com/2018/04/12/in-search-of-caprina/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/category/norwich-streets/

Great! We missed you

LikeLike

As Arnie said, ‘I’ll be back’ (from time to time)

LikeLike

Dear Reggie, thanks so much for another fascinating ‘read’, excellent!

Don’t forget, I’d really be so grateful to read a full article on ‘The Tabernacle’

which stood in Bishopgate (where the Law Courts now stand) from 1753-1953.

Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you Richard.

LikeLike

Not in Norwich but Norfolk, Princess Sophia Duleep Singh was a notable suffragette. One the authorities did Not want to arrest, possibly because she was Queen Victoria,s God child..

LikeLike

Hi Alison, Thank you for your comment. Anita Anand’s book on Sophia Duleep Singh is in front of me as I write. I had intended to include Sophia despite the fact that she was brought up in Elveden, on the wrong side of the Suffolk/Norfolk border, but Norwich provided a richer seam than initially expected.

LikeLike

More absolutely riveting history. Please keep it coming. I am President of Victoria Bowling Club on Trafford Road and our lovely green predates all the development of the Trafford Estate. We are worthy, I believe , of more investigation from you and would welcome a chance to open our history to you.

LikeLike

I appreciate your kind words, Roy. I am intrigued by the number of bowling greens on old maps and it would be good to get an idea of the extent of the sport in Victorian/Edwardian times.

LikeLike

Thank you, Reggie, for another superb read resulting from some great research. I’m curious about the surveillance photos. Wouldn’t the police have taken mugshots when they were arrested?

LikeLike

Hi Paul, The suffragettes were not compliant and wouldn’t pose for mugshots. The Criminal Record Office therefore took clandestine photos in the exercise yard at Holloway using a 11.5 inch telephoto lens. There appears to be evidence ( shorturl.at/oU479 ) that the suffragette Evelyn Manesta had to be restrained to make her face the camera (the restraining arm was later airbrushed out). So photographs had to be taken, one way or another in order to compile a montage of activists for future occasions. Read: http://www.notbored.org/suffragettes.html

LikeLike

Grateful thanks, Reggie, for your tireless researches. I am inspired by those courageous suffrage campaigners, who faced hard labour, force-feeding and even death for a notion that today seems self-evident: one (wo)man, one vote. How saddened they would have been by the 2012 shooting of 14-year-old schoolgirl activist Malala Yousufzai, a campaigner for the right to education for Pakistani girls (deemed ‘an obscenity’ by Taliban men). I believe our outrage sprang partly from the national re-education those women brought about in the early 20C. It’s regrettable it didn’t extend to our imperial forefathers, whose blind indifference to the plight of the women they governed, for decades after, was an opportunity missed, and left many millions of girls in our ex-colonies doomed to lifelong inequality, subjugation and indignities.

LikeLike

Thank you Keith. Yes, how courageous were those young women and how barbaric their treatment. And how disheartening that that a century later there is still not universal suffrage.

LikeLike

Welcome back! It was worth waiting for this in depth post on a struggle often overlooked locally. My mother was a supporter of the suffragettes when she was a teenager though by then (1920’s) the fight was for universal adult suffrage and I remember her always being determined to vote in every election, National or Local saying that people had died so she could.

Was the Princes Restaurant in Castle St the forerunner of the one I remember on Guildhall Hill in the premises now occupied by the TSB bank?

Keep you a goin’ bor Don Watson

LikeLike

Hello Don, Book written and hoping to have it printed this autumn. Will try my best to keep a goin’ but perhaps on a less regular basis. . I shall have to look into the tea rooms on Guildhall Hill; haven’t heard they might have belonged to Mrs Cushion.

LikeLike

You certainly did not waste your time when you were AWOL – yet another great and interesting post! Thank you for this and alleviating the ‘withdrawal symptoms’ I developed during your absence.

LikeLike

Your comments much appreciated, Haydn. Looking into the Norwich suffragettes was deeply fascinating and quite affecting. I feel sure there are many more stories of young Norwich suffragettes still to be told.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank You. Looking forward to future installments.

LikeLike