Knighted by King Charles II in St Andrew’s Hall, Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682) was probably Norwich’s most famous inhabitant of the seventeenth century. He was born in London, the son of a silk merchant and, after being educated in Oxford, Padua, Montpellier and Leiden, settled in Norwich where he practiced as a physician until he died [1].

Sir Thomas Browne, from St Peter Mancroft, Norwich

He was famed as a polymath whose writings reveal an inquisitive mind that explored subjects as diverse as: the fault line between his training as a physician and the Christian faith (in Religio Medici, 1643); his debunking of myths and falsehoods (Pseudodoxia Epidemica, 1646); the incidence of the number five in patterns in nature (The Garden of Cyrus, 1658); and his celebrated and lyrical musings about death, prompted by the discovery of funerary urns in a Norfolk field (Hydriotaphia, or Urne-Buriall, 1658).

This was at a time when modern science was in its infancy. The scientific method, promoted by Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626), involved framing hypotheses based on observations viewed through the filter of scepticism.

Sir Francis Bacon 1561-1626. From Gainsborough Old Hall, artist unknown

Browne was appropriately sceptical in his examination of Vulgar Errors (Pseudodoxia Epidemica) like: Does a carbuncle give off light in the dark? and, Do dead kingfishers make good weathervanes? He even attended the trial in Bury St Edmunds of two women who were hanged for witchcraft. But the Enlightenment had barely got going and the proto-scientist Browne found himself straddling two worlds that had yet to drift apart – even Sir Isaac Newton sought the philosopher’s stone that would turn base metal into gold.

My first encounter with Sir Thomas was when I was trying to understand how plant cells and other solid bodies pack together [2]. I had gained some insight from another early scientist, Stephen Hales (1677-1761). By squashing a pot of pea seed then counting the number of flat faces impressed onto each seed by its neighbours, Hales came up with the number 12. You can make a dodecahedron by joining together 12 pentagons, making one of only a handful of ‘ideal’ solid bodies (another is a cube made of six squares). Plato knew this [3].

Rotating dodecahedron. By André Kjell, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

But in real life, the shapes of plant cells are far from perfect and don’t pack together neatly like Platonic Lego. Instead, they tend, on average, to be 14-sided and each side tends, on average, to be a pentagon [3]. Nevertheless, this idea of fiveness took me back a further century to fellow citizen Thomas Browne.

Frontispiece to The Garden of Cyrus (1658). The founder of the first Persian Empire, Cyrus, is believed to have based the optimal spacing lattice for planting trees on the quincunx.

In The Garden of Cyrus or The Quincuncial Lozenge (1658) [4] Browne developed his ideas about the quincunx – the X-shape with four points forming a square or rectangle with a fifth point in the centre.

Browne saw this pattern throughout nature; he saw the quincunx on the trunk of the ‘Sachell palme’ and in the fruits of pineapple, fir and pine. In ragweed and oak he also noted that successive leaves followed a spiral, with every fifth lined up along the stem. These were, before the word, explorations into phyllotaxis or the pattern in which leaf buds emerge from the shoot tip (paired, alternating, spiral). Now, more than 300 years later, the spiral pattern is known to be far more complex than the quincunx. The number of intersecting left-handed-and right-handed spirals tend to be successive numbers on the Fibonacci series, usually 5 and 8, or 8 and 13. (Fibonacci’s series is 0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21 etc, where the next number is the sum of the last two). Browne may not have been correct but he was there in the first flush of modern science and deserves credit for offering a mathematical basis for patterns in nature.

Left- and right-handed spirals in the base of a pine cone. Picture © Paul Garrett [5].

electricity, pubescent, polarity, prototype, rhomboidal, archetype, flammability, follicle, hallucination, coma, deductive, misconception, botanical, incontrovertible, approximate, and an early example of ‘computer’.

Despite the scepticism required of a follower of Bacon, and ‘the scandal of my profession‘, Browne remained a convinced Christian who examined his spiritual beliefs in his most famous book, Religio Medici [6].

1736 edition of Browne’s Religio Medici. Courtesy of Glasgow University Library

He was surprisingly tolerant for his time. In the first unauthorised edition of Religio Medici (The Religion of a Physician) in 1642, Browne expressed unorthodox religious ideas including the extension of toleration to infidels and those of other faiths. When the authorised version appeared the following year some of the controversial views had been excised but this didn’t prevent its inclusion on the papal list of prohibited books.

Browne’s major works were written in Norwich, at his house near St Peter Mancroft, close to the Norman marketplace.

Browne’s world. Cole’s map of 1807 shows Thomas Browne’s house (red) and St Peter Mancroft (yellow) with the Haymarket between.

Thomas Browne’s House off the Haymarket, by AW Howlings 1907. This version is changed little from a drawing of 1837 when the pairs of windows either side of the corner pillar were bow-fronted. Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM: 1907.33.2.

The fireplace and overmantel from Sir Thomas Browne’s House by Miss Ellen Day and Mrs Luscombe 1841.Norfolk Museums Collections NWHCM: FAW19.

After posting this article, Wayne Kett of the Museum of Norwich informed me that this overmantel was in storage as part of their collection. One source had indicated that the coat of arms was that of James I but it seems to be that of Charles II, which makes more sense since – as we will see – it was he who knighted Browne.

Dr Browne’s overmantel ©Norfolk Museums Service

In 1671, the royal court of Charles II came to Norwich. The diarist and gardener John Evelyn was part of the entourage and wrote, “His whole house and garden is a Paradise & Cabinet of rarities, & that of the best collection, especially Medails, books, Plants, natural things” … “amongst other curiosities, a collection of the Eggs of all the foule & birds he could procure … as Cranes, Storkes … & variety of waterfoule” [6]. What Evelyn saw was the first attempt at listing the birds of Norfolk.

The house was demolished in 1842 but we know – because a green plaque tells us so –that it stood approximately where Pret a Manger is now housed in Haymarket Chambers, at the junction with Orford Place. Historian AD Bayne confirms that ‘Sir Thomas Browne is supposed to have lived in the last house of the southern end of the Gentleman’s Walk, where the Savings Bank now stands’ [7]. But the bank stood in the way of progress.

Former site of Sir Thomas Browne’s house. Pret a Manger currently occupies the ground floor of George Skipper’s Haymarket Chambers (1901-2). It was originally home to JH Roofe’s superior grocery store with the Norwich Stock Exchange above. ©RIBApix

To allow the new trams to turn the corner more easily into Orford Place, the Norfolk and Norwich Savings Bank was demolished and replaced with Skipper’s curved design. The corner-cutting is shown on the 1884 OS map that we’ll bear in mind while trying to figure out where Browne’s Garden House lingered on from 1844 to 1961.

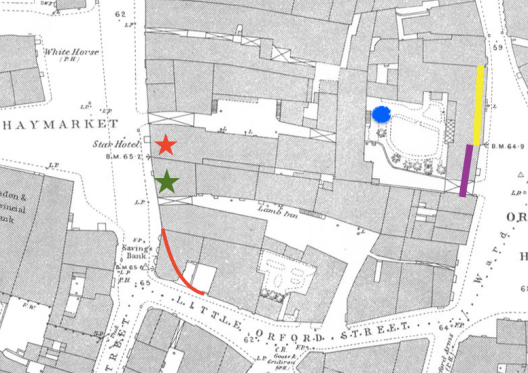

Green star = Green’s Outfitters; red Star = Star Inn; yellow line = Livingstone Hotel; purple line = Green’s Orford Place branch; blue circle = approximate site of Browne’s Garden House. OS map 1884

According to George Plunkett, numbers 3-5 Orford Place (Little Orford Street on above map), which was demolished in 1956, had a stone inscription stating that this was the site (probably the side) of Thomas Browne’s house [8]. But Plunkett placed Browne’s timber-framed garden house a little distance from the main house, between the Livingstone Hotel (yellow line) and Green’s shop (green star). He said, ‘only the peak of its tall attic gable visible above the roof of the adjacent Lamb Inn’. So it couldn’t have been in Lamb Inn yard, adjacent to the former site of Browne’s house.

![Orford Hill 16 Livingstone Hotel [1361] 1936-08-30.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwichdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/orford-hill-16-livingstone-hotel-1361-1936-08-30.jpg?w=529)

The Livingstone Temperance Hotel 1936 ©georgeplunkett.co.uk

Green’s Orford Place Branch, post 1936. ©Norfolk County Council at Picture Norfolk

On the opposite (Haymarket) side of this block of buildings, Green’s main branch stood adjacent to Skipper’s Haymarket Chambers. The slight bend in the building line marks where, around 1900, Green’s expanded into the former Star Hotel.

Green’s in 1959. The upper floors of Skipper’s Haymarket Chambers are just visible, right, separated from Green’s by the entrance to the Lamb Inn. Photo courtesy of Archant Library.

Browne’s main house disappeared long before modern ideas of conservation, but the loss of his garden house in 1961 now seems an inexcusable loss. His botanical garden had been admired by John Evelyn and ‘Fellows of the Royal Society (thought it) well worthy of a long pilgrimage’ [7]. Our Protestant Dutch refugees – who held annual competitions called Florists’ Feasts [9] – imported a love of plant breeding and it would be surprising if, in such an environment, Browne’s garden was restricted to medicinal plants.

In 1950, Noël Spencer visited Greens when they ‘were using the Livingstone as a shop and, while making a purchase there (i.e., Green’s Orford Place branch), I noticed an ancient building in the yard behind, and obtained permission to draw it [10].’ This places the Garden House in the yard marked with a blue dot on the 1884 map, above.

Drawing by Noel Spencer, former Head of the Norwich School of Art, of Sir Thomas Browne’s Garden House before its demolition in 1961. From [10] ©Estate of Noel Spencer.

Further confirmation for the location of Browne’s Garden House came after this article was posted. On Twitter, Bethan Holdridge – Assistant Curator at Strangers’ Hall Museum – replied, mentioning that two of Browne’s Garden House doors in the museum were listed as being given by ‘Messrs Littlewood’ 1961. Also, ‘lying behind former Livingstone Hotel, Castle Street; part of premises of Messrs Green, outfitter 9 and 10 Haymarket.’

To supplement his home garden Sir Thomas leased a plot of land from the Cathedral, known as Browne’s Meadow. In his Adventures of Sir Thomas Browne in the 21st Century, Hugh Aldersey-Williams writes that Browne ‘let it go’, to see what would grow if untended [1]. After Browne died, the ground was used to produce vegetables for the Cathedral, then used as allotments for residents of Cathedral Close. Now it is a car park.

‘Browne’s Meadow’ on the south side of the Cathedral Close

In his book, Urn Burial (1658), Browne explored thoughts prompted by the discovery of funerary urns in a field some 12 miles north of Norwich: ‘Life is a pure flame, and we live by an invisible Sun within us’.

Title page of Sir Thomas Browne’s Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial 1658

This was in the parish of Brampton, near the Pastons’ Oxnead Park where Sir Robert Paston had dug up urns containing ashes and coins (perhaps to pay the ferryman). In the early 1800s the historian Blomefield visited the field where he observed that urns were buried close enough to the surface to have been skimmed by the ploughshare. He observed that this site was near a fortified Roman town and that the Roman name Brantuna meant ‘the place where bodies were burned‘ [11].

Sir Thomas Browne died on the 19th October 1682. One claim is that he died, having eaten too plentifully of a Venison Feast [12] but others believe this was out of character for such an abstemious man. He was buried in the chancel of St Peter Mancroft, some 200 yards from his house.

Sir Thomas Browne’s wall monument in the chancel of St Peter Mancroft. The lower panel records that he lies near the foot of this pillar.

In 1905, equidistant between his house and church, the city commemorated an adopted son by unveiling one of its rare statues. From his vantage point above the old hay market, Browne holds the base of a Romano-British funerary urn and meditates on death.

Browne asked, “… who knows the fate of his bones, or how often he is to be buried? Who hath the oracles of his ashes, or whither they are to be scattered? … To be gnawed out of our graves, to have our skulls made drinking-bowls, and our bones turned into pipes to delight and sport our enemies, are tragical abominations [13].” This turned out to be a premonition.

Sir Thomas Browne lay undisturbed until 1840 when workmen are said to have broken the lid of the lead coffin with a pickaxe while digging the grave of Mrs. Bowman, wife of the then Vicar of St. Peter Mancroft. Mr Fitch, a local antiquarian, was suspiciously at hand and it is not clear whether the desecration was accidental or deliberate. Either way, the sexton, George Potter, removed the skull and some hair. The skull came into the possession of the surgeon, Edward Lubbock, upon whose death it passed to the old Norwich and Norfolk Hospital Museum on St Stephen’s Road (read various explanations of this dubious episode in [12-15]). Despite requests from the church, the skull remained on display at the hospital and was only reunited with Browne’s bones in 1922.

At the time of the reinterral the registrar recorded Browne’s age as 317.

Sir Thomas’s coffin plate, which had broken in two during attempts to remove it, had also been ‘mislaid’. One half of this 7×6 inch brass plate lies with other Browne memorabilia in a glass case in the St Nicholas Chapel of St Peter Mancroft.

The accompanying text makes interesting reading, stating that it was collector and antiquary Robert Fitch who further disturbed Browne’s peace by removing his skull.

An impression of the coffin plate revealed an inscription probably composed by his eldest son Edward, physician to Charles II, and President of the College of Physicians [15].

Impression from the coffin plate of Sir Thomas Browne [14].

Postscript

Thomas Browne’s knighthood: Ambiguity surrounds the circumstances of Thomas Browne’s knighthood. In 1671 King Charles II and his court came to Norwich where he stayed at the Duke of Norfolk’s Palace off present-day Duke Street (causing the famous indoor tennis court to be converted into kitchens). The corporation paid £900 for a sumptuous banquet at the New Hall (now St Andrew’s Hall) after which the king conferred honours.

The New Hall, where Browne was knighted, once belonged to the Black Friar’s but was bought for the city from Henry VIII. The Duke’s Palace is to the left. From Samuel King’s map, 1766

According to some accounts Browne was unexpectedly knighted when the mayor, variously named as Henry Herne or Thomas Thacker, ‘earnestly begged to be refused’ and so the honour passed along the line. This played into the idea that a promiscuous monarch with several mistresses was as free in conferring honours as he was lax in his private life. Apparent confirmation of the king’s fickleness came within 24 hours when King Charles knighted 13-year-old Henry Hobart at Blickling. But Trevor Hughes picked out inconsistencies between various accounts, such as uncertainty about the name of the reticent mayor [16]. A more sympathetic interpretation was given by historian Philip Browne who wrote: ‘After dinner his majesty conferred the knighthood on Dr Thomas Browne, one of the most learned and worthy persons of the age. The mayor, Thomas Thacker esq. declined the honour’ [17]. That is, the internationally famed Dr Browne was not accidentally knighted but honoured in his own right.

©2020 Reggie Unthank

––oOo––

Recently reprinted. ‘Colonel Unthank and the Golden Triangle’ contains much more about the development of the Golden Triangle than covered in my blog posts, including photographs of the Unthank family.

Available online. Click Jarrolds Book Store or City Bookshop

Sources

- Hugh Aldersey-Williams (2015). The Adventures of Sir Thomas Browne in the 21st Century. Pub: Granta. Highly recommended.

- Clive Lloyd (1991). How does the cytoskeleton read the laws of geometry in aligning the division plane of plant cells? Development, Supplement 1, pp 55-65.

- Peter S Stevens (1976). Patterns in Nature. Pub: Peregrine Books.

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Garden_of_Cyrus

- https://www.projectrhea.org/rhea/index.php/MA279Fall2018Topic1_Phyllotaxis

- Ruth Scurr (2016). https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/thomas-browne/

- AD Bayne (1869). A Comprehensive History of Norwich. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/44568/44568-h/44568-h.htm

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/old.htm#Orfoh

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/08/15/going-dutch-the-norwich-strangers/

- Noël Spencer (1978). Norwich Drawings. Pub: Noel Spencer and Martlet Studio

- Francis Blomefield (1807). An Essay Towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk vol 6. Online at: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-hist-norfolk/vol6/pp430-440

- https://penelope.uchicago.edu/skullnotes.html

- http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/28/dickey.php

- https://wellcomecollection.org/works/ykn7hdpz/items?canvas=5&langCode=eng&sierraId=b30623340

- http://drc.usask.ca/projects/ark/public/public_image.php?id=2384

- Trevor Hughes (1999). Sir Thomas Browne’s Knighthood. In, Norfolk Archaeology vol XLIII, part 11, pp 326-331.

- Philip Browne (1814). The History of Norwich from the Earliest Records to the Present Time. Pub: Bacon, Kinebrook & Co.

Thanks: I am grateful to Chris Sanham, verger at St Peter Mancroft, for his assistance.

Fascinating detective work on the location of Browne’s Garden House. Tragic to think it survived until as late as the 1960s only to be demolished. Oh to be a time traveller!

LikeLike

I agree. So near yet so far.

LikeLike

In these times of non-travel, these are as good as it gets to being transported back to the homeland. Great stuff.

LikeLike

It is often difficult making that imaginative leap between the city we know and what it must have been like when Browne was alive… which is why the loss of his Garden House as late as 1961 is so annoying. Thank you Daniel.

LikeLike

Another great post honouring one of Norwich’s most worthy adopted sons. When I first started work at the Norwich Union’s local branch the Garden House was pointed out to me as a fire hazard – the whole block was (and still is) a maze of interlocking buildings and inaccessible small spaces. I suspect that the fire risk posed by a derelict timber-framed building had something to do with its demolition.

Don Watson

LikeLike

Thank you Don. Did you ever visit the Garden House? It would be good to be able to position it exactly in that space behind what became Littlewood’s on the Orford Hill side.

LikeLike

Hopefully the ‘blocking plans’ for Norwich still exist.The Aviva Archivist ought to be able to find them – there were several volumes of very detailed hand-drawn plans covering the central area of the city. Insurers made them to know exactly what and how much of an area they were covering

LikeLike

Thank you Don. I’ll get onto this.

LikeLike

What an interesting investigation! I would love to have seen Sir Thomas’ Garden House! I hope you manage to find something of use from the Aviva insurance plans.

LikeLike

Gardens are ‘soft’ history so we can only guess what Sir Thomas Browne’s and Sir JE (Linnean Society) Smith’s gardens were like. I would also loved to have seen the gardening practices introduced by our Dutch Strangers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Norwich, City of the Plains | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

There is (or was, last time I went in there) a replica skull in the Sir Thomas Browne Library at the NNUH. Interesting to read about someone whose name I knew but really didn’t know anything about!

LikeLike

I knew the skull was in the old N&N hospital. Is it now in the Colney hospital?

LikeLike

Yes it was at the new hospital. I’ll have to have a look and see if it is still there when I next get a chance.

LikeLike

Pingback: Sculptured Monuments | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Am I right in thinking that Greens on Haymarket incorporated a sizeable Tudor mansion with its own undercroft, still there underneath Littlewoods- or is that actually Thomas Browne’s aforementioned Garden House? If memory serves you could walk through Greens to get to White Lion St and I think a loke to one side did the same. I went to the CNS as a youth and the debating society was named after Thomas Browne. I don’t ever remember arguing “This House does not believe in witches”. Alas, Browne did. One of the episodes in his life that is seldom mentioned is his involvement in the 1664 Lowestoft Witch Trials as a witness- for the prosecution! He was one of the most eminent minds of his time, Matthew Hale was no Judge Jeffreys, yet, between them, they could help send two innocent women to the gallows on evidence that would not be used to put down a cat. Growing pains for a New Age. Mercifully, after 1699 this kind of barbarism became a thing of the past- at least in England! MGR.

LikeLike

FatFace on Haymarket/The Walk incorporates a medieval building, which I have seen on Heritage Open Days. Greens outfitters was next door where Primark now is. Noel Spencer, former head of the School of Art, could see Thomas Browne’s garden house out of an internal window of Greens on the Orford Hill side . Maps show an open courtyard there; did you ever notice outhouses when wandering through Greens?

LikeLike

So, interesting remains yet to be seen, then! I vaguely remember going out into an alleyway at the back of Greens in order to go back into the store at the front! As I would have been seven or eight at the time it’s quite possible I’ve confounded this with the yard to the Lamb Inn next door, which in those days would have been a short cut through to Orford Place or, just as likely, Frank Price’s premises in Botolph St.- definitely on the family watch! Capricious, the powers of memory. I think Greens became the Belfast Linen Store for a few years,yes? As an habitué of Wilson’s Music Shop on White Lion Street It took me some years to clock why the end of the shop facing the Bell Hotel was weatherboarded, likewise buildings on the sharp bend into Redwell St. from the top of St. Andrew’s alongside the liberties taken to one side of Armada House. At the turn of the C19/C20 they didn’t pull down any more than they absolutely had to, in this case to make it easier for the trams. A sharp reminder that even buildings aren’t set in stone! …… MGR.

LikeLike

It is not the frontispiece of ‘Urn-Burial’ which you’ve posted ( happens to be a photo of my personal copy ) its the title page. You have however posted the frontispiece to ‘The Garden of Cyrus’. ‘Urn-Burial’s frontispiece is an illustration of four burial Urns.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I have made the correction.

LikeLiked by 1 person