Over the years Norwich’s largest public green space has been known as Chapel-in-the-Fields, Chapel Fields, Chapple/Chapply/Chaply/Chapley Field, and now Chapelfield Gardens [1]; my daughters call it Chappy. We saw the area last when genteel Georgians promenaded around its triangular walk [2] but this only occupied a thin slice of time for the name goes back a further half millennium to when John le Brun founded the Chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Fields (1250). This evolved into the College of St Mary in the Fields, part of which was to be incorporated into the Georgian Assembly House (1745-6).

Braun and Hogenberg’s prospect of 1581 is based on Cuningham’s map of 1558 so provides a glimpse of Chapel Field around the time of Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. In 1569 the ownership of Chapel Field was transferred to the city. The map shows this sector dominated by two areas of open ground: the land behind Chapel Field House and a triangular meadow grazed by cows and occupied by figures with bows and arrows. This was at a time when it was still compulsory for men between the ages of 15 and 60 to prepare for war and we see them practicing archery under the walls. But warfare was changing and by the latter part of the century the field became the mustering ground for the city’s trained artillerymen.

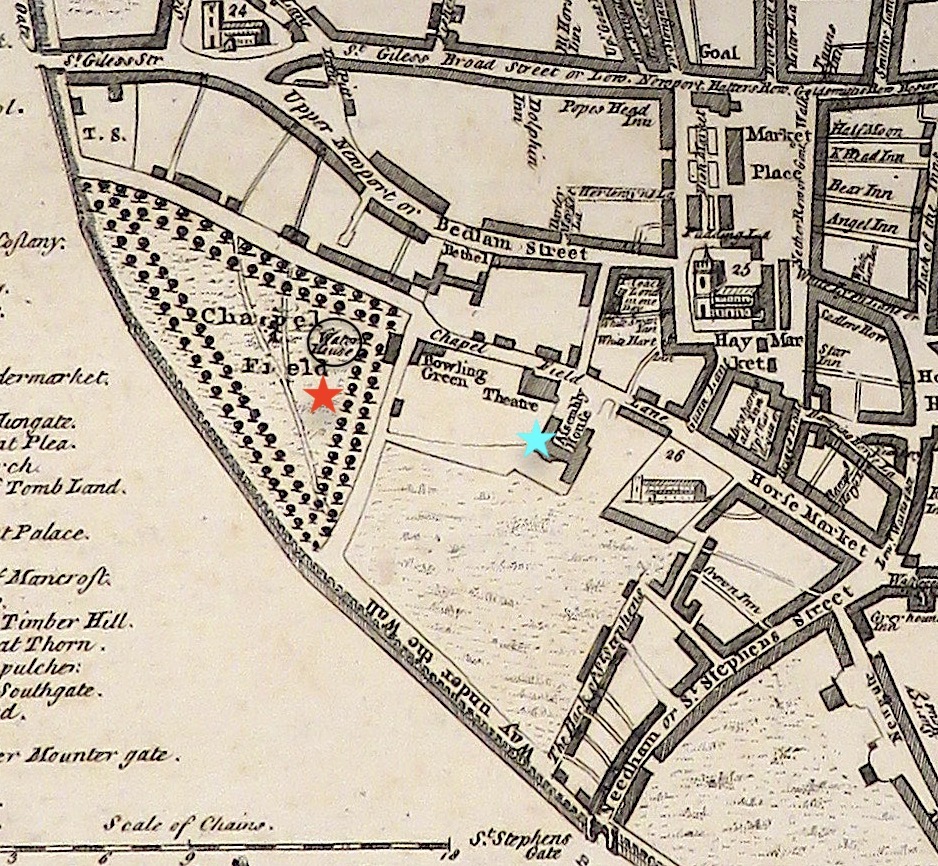

By the time of King’s plan of 1766 the two parts were still largely open ground. Only minor inroads were made by the bowling green, theatre and Assembly House, which provided entertainment for leisured Georgians. On the triangular field we see the double row of elms that lessee Thomas Churchman’s planted for his promenade [2]. This latter portion would survive as present-day Chapelfield Gardens.

A generation later, Chapel Fields still embodied a sense of bucolic openness as conveyed in the etching by John Crome (1768-1821). The city had always allowed Chapelfield to be used as a public space and in 1656 resisted Lady Hobart’s attempt to prevent citizens passing through [3]. Infilling with shanty housing was the norm in the rest of the city but the only signs of encroachment on rustic Chapelfield are the post-and-rail fencing and the high wall to the left (possibly part of the city wall) .

From the beginning of the eighteenth century the fields were fenced in [3]. In 1867 the council erected iron railings [4], which would be removed in World War Two, purportedly to make guns. This would have been the ‘massive palisade’ supplied by W S Boulton (later of Boulton & Paul) who, ‘produces every kind of railing … also mincing and sausage machines’ [5].

Chapel Fields lies in the crook of the protective arm provided by the city walls, built about 1300. Some 500 years later the gates at its southern and western extremities were demolished to ease the flow of horse-drawn traffic: St Giles’ Gate in 1792 and St Stephen’s Gate a year later. The walls were disappearing too, signifying a loosening of the hold of the medieval past and allowing – if only notionally – the escape of noxious air. In the 1860s, some of the wall around Chapelfield was used as hardcore for the new Prince of Wales Road that connected the markets with the newly arrived railway [6]. Some of the ‘Chapelfield’ wall had been breached by houses built against them.

In 1969, these houses were demolished to make way for the ring road [7].

King’s map of 1766 shows a water house within Churchman’s triangular walk, part of the corporation’s scheme to supply water to the city. Water pumped from the river at New Mills (near Westwick Street, upstream of the built-up area) supplied Chapelfield and Tombland. The Tombland works were described in 1698 by Celia Fiennes as ‘a great well house with a wheele to wind up the water … a large pond walled up with brick a mans height … (and) a water house to supply the town by pipes’ [quoted in 8]. This is commemorated by John Henry Gurney’s obelisk and fountain of 1850.

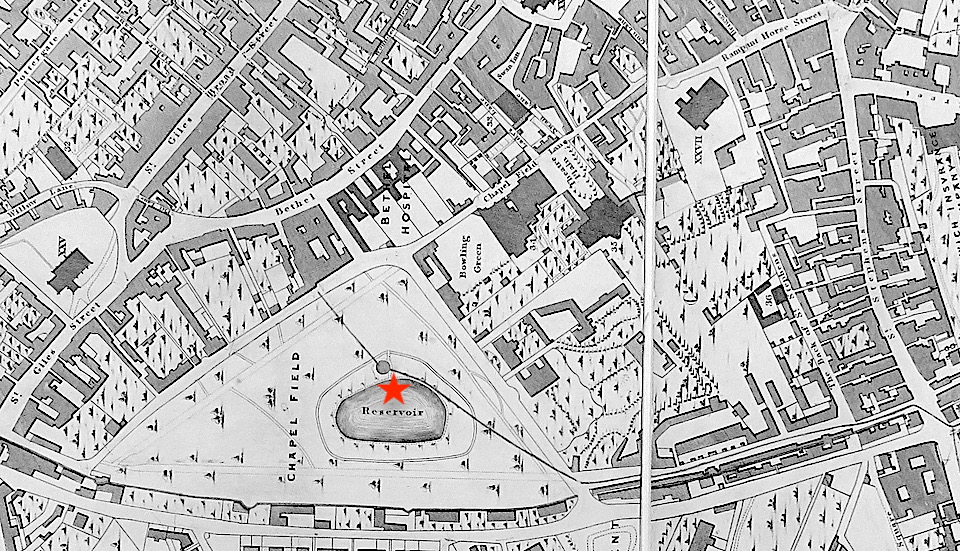

Supply of unfiltered water was therefore restricted to a few parts of the city – and then only to those who would pay for the connection. In 1792, supply was taken over by the Norwich Waterworks Company who built the water tower and reservoir in Chapel Field that appear on Millard and Manning’s map of 1830 [9].

The presence of waterworks in Chapelfield had disturbed the illusion of a bosky retreat where the gentility could associate and by 1840 the park had become ‘the resort of loose and idle boys’ and washerwomen [9]. One idea had been to dignify the site by placing a statue of Nelson on an island in the middle of the reservoir [3]. This never happened and the statue was located, instead, in the cathedral’s Upper Close.

In 1852 the Waterworks Company agreed to hand the land over to the corporation provided they laid it out as a public garden, which they did. By designating Chapelfield Gardens a public park the site was protected from the terraced housing being built just the other side of the city wall.

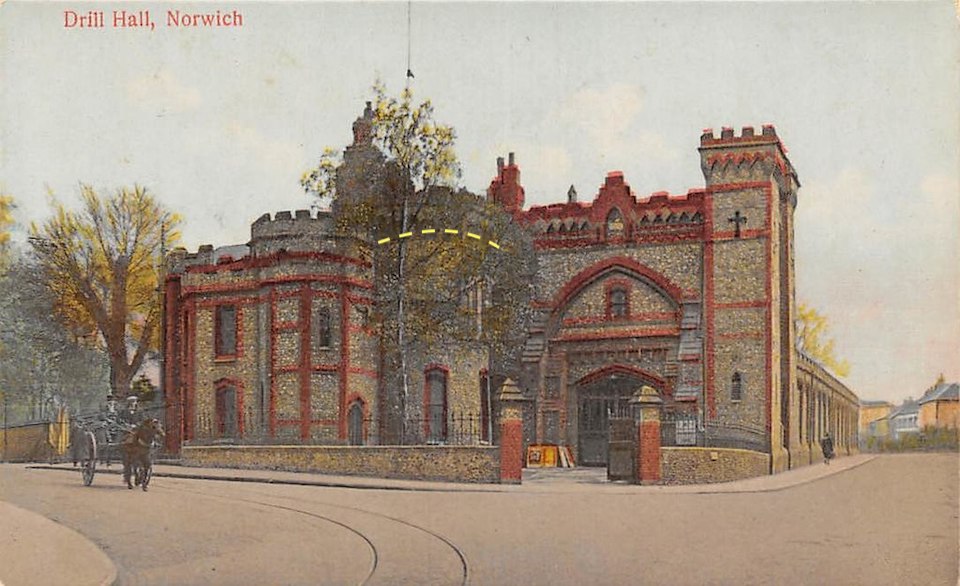

In 1866 the corporation offered the north-west corner of Chapelfield Gardens to the militia for building a drill hall [5]. This castellated Neo-Gothic building, designed by the City Surveyor, Ernest Benest, incorporated part of a tower from the old city wall. The triangular shape of Chapelfield Gardens would be lost when this corner, and the Drill Hall, were flattened beneath the inner ring road of the C20.

From within this lost north-west corner of Chapelfield Garden we see the back of the Drill Hall and beyond this the Catholic Cathedral, only just completed in 1910. And those must be Mr Boulton’s sturdy iron railings, removed in World War II.

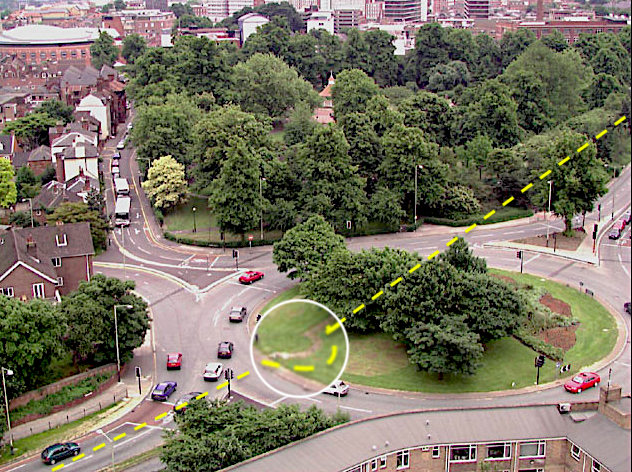

The Drill Hall was demolished in 1963 but the position of the old city-wall tower incorporated into its structure is commemorated by a semi-circle of cobbles on the Grapes Hill roundabout, constructed as part of the 1968-1975 Inner Link Road.

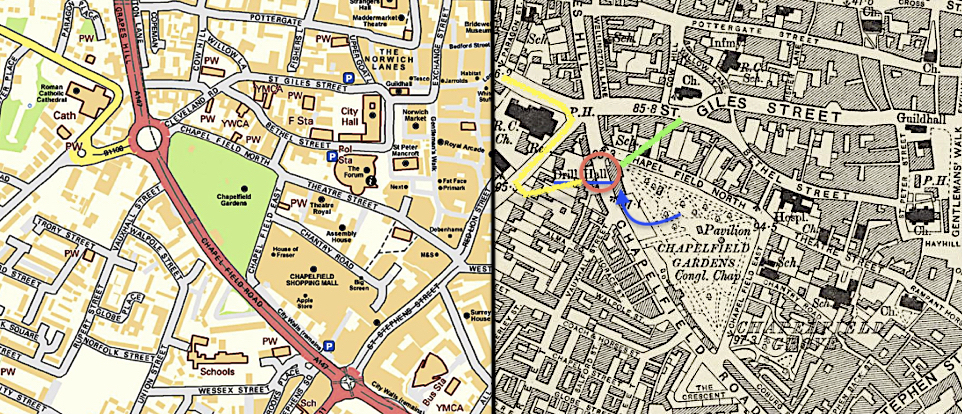

To connect the roundabout with incoming traffic from Earlham Road – which had previously gone straight across to St Giles Street – an awkward fiddler’s elbow (yellow) was created when vehicles were diverted a little way up Unthank Road. Traffic was reconnected with St Giles Street via a spur off the roundabout, creating Cleveland Road (green) in the process. It probably made sense at the time.

George Plunkett’s invaluable archive of twentieth century photographs shows us the Earlham Road/St Giles Street intersection before the map was redrawn in the late 1960s. Here we look down the narrow street that appears as St Giles Hill on the 1884 OS map and as Grapes Hill in 1908. This was some 60 years before the houses were demolished in readiness for the dual carriageway and the pedestrian flyover built over it. To the far left, at No 1 Earlham Road, is the eponymous Grapes Hotel. It was the only building on the hill to survive the ring road but it was to give way to retirement homes built around 2000. I can recall being able to touch the upper floor of the former Grapes Hotel from the gangway up to the footbridge.

Inside the gardens, one of its most exotic inhabitants was the iron pavilion designed by Thomas Jeckyll. Made by Barnard Bishop and Barnards, and with much of the bas-relief work being forged by Aquila Eke (George Plunkett’s great uncle) it won a gold medal at the Philadelphia exhibition of 1876. Four years later it was bought by the Norwich corporation for £500 and installed in Chapelfield Gardens. I’ve written at length about Aesthetic Jeckyll and his designs for Barnards’ Norfolk Iron Works [e.g., 11], so I won’t run on, but this was the famous ‘Pagoda’, enclosed by railings in the form of uber-fashionable sunflowers – an icon of the Japanese-influenced Aesthetic Movement, here in provincial Norwich. Yet, despite it being a triumph of Norwich craftsmanship, the modernists who wrote the City of Norwich Plan for 1945 judged the Pagoda to be dispensable and so it was demolished in 1949. As Gavin Stamp wrote in Lost Victorian Britain, ‘Victorian, quite simply, was a term of abuse’ during the post-war period.

Designed by Jeckyll, the fabric hangings that once decorated the Pagoda are conserved in the Norwich Castle Study Centre.

Another occupant of Chapelfield Gardens was a thatched teahouse, known as King Prempeh’s Bungalow, built about the time of the Ashanti campaign in West Africa. Prempeh the First (1870-1931), who had tried to negotiate peace with the British, was captured by an expeditionary force led by Robert (‘Scouting for Boys’) Baden-Powell and sent into exile. In 1902, the Ashanti Kingdom became part of the Gold Coast colony. When Prempeh – once ruler of all he surveyed – was eventually released he found himself Chief Scout of what was now a British protectorate [12].

Surrounding Chapelfield Gardens

From about 1815 the New City arose outside the walls on the south-west side of Chapelfield Road. This signalled the start of the expansion of working-class housing away from the insanitary muddle of the old city. A piece of land once used as a market garden became Crook’s Place and along with Union Place and Julian Place these terraces of small houses were built to accommodate an influx of workers from the countryside [13]. Mostly back-to-back, these modest dwellings with shared privies and water pumps proved to be insanitary and were demolished during rounds of twentieth century slum clearance. A generation later, terraced housing on the Steward and Unthank estates was built to higher standards and continued the city’s westward expansion well beyond the pull of the medieval walls [13].

Built better for polite society, the V-shaped Crescent (1821-1827) survives into the twenty-first century. Nearby, the distinctive Gothic House was demolished as part of the Vauxhall demolition scheme of the 1960s. The Gothic Revival, mostly encountered on Victorian non-conformist chapels around Norwich, hardly touched the city’s domestic housing; the Gothic House is a rare example of this style, here applied as a facade to an older building [14].

The street bounding the gardens to the north, Chapelfield North, is architecturally rich; it hasn’t altered significantly during my 40 years in the city although the ebb and flow of traffic seems to have changed according to various schemes. One bystander that has overseen a more dramatic change in transport fashion is The Garage, now a centre for performing arts.

Originally, The Garage was built as the new motor works for Howes & Sons Ltd.

In this photograph Howes were announcing themselves as ‘coachbuilders’ at a time when coachwork had come to mean the body of a motor vehicle. But this was just a breath away from a world when Howes built horse-drawn carriages.

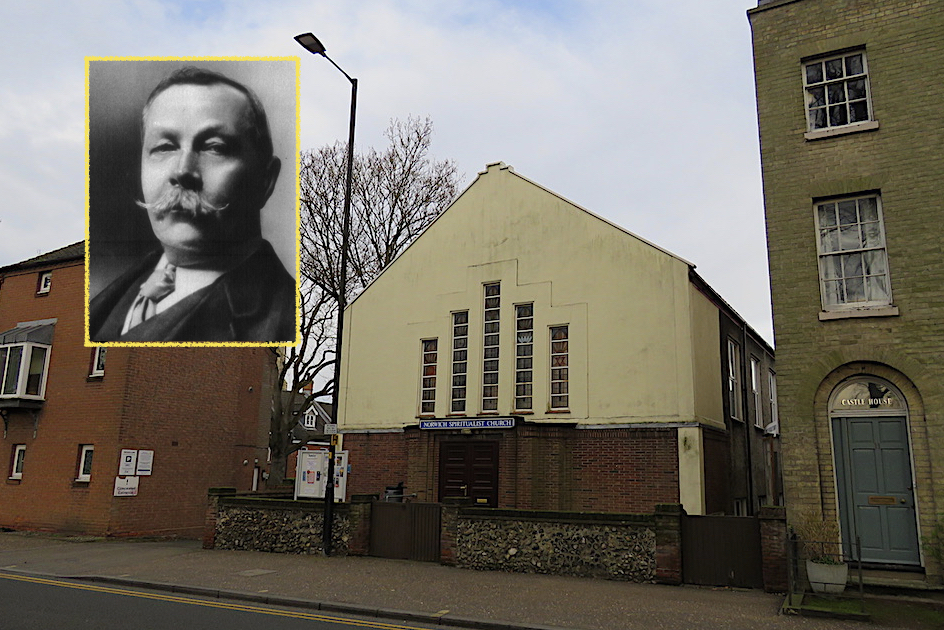

A twentieth century addition to Chapelfield North is the Norwich Spiritualist Church. Built by RG Carter in 1936, this single-storey building was part-funded by proceedings from a post-WWI spiritualist meeting addressed by the faith’s most famous adherent, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

The third of the triangle of streets around Chapelfield Gardens is Chapelfield East, which divides the gardens from the larger block that once housed Caley’s chocolate factory (later, Rowntree Mackintosh then Nestlé). Demolished to make way for the Chapelfield Shopping Centre (2005) this complex was – with a nod to its ecclesiastical heritage – recently renamed as Chantry Place.

On this street Chapelfield East Congregational Church once stood, a prominent landmark with twin 80-foot towers. As George Plunkett noted [15], a stranger could have been excused for thinking it was this chapel that gave name to the neighbouring public garden. Of course, it was far too young, arising in 1859 to be demolished in 1972.

© 2022 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- Francis Blomefield (1806). ‘History of the County of Norfolk’ 4, part 2 Chapter 42 City of Norwich. Online at: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-hist-norfolk/vol4/pp145-184#h2-0003

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2021/11/16/georgian-norwich/

- Frank Meeres (2011). The Story of Norwich. Pub: Phillimore & Co. Ltd.

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1001645

- A.D. Bayne (1869). A Comprehensive History of Norwich https://www.gutenberg.org/files/44568/44568-h/44568-h.htm

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/cat.htm#Chafe

- Margaret Pelling (2004). Health and Sanitation to 1750. In, Norwich since 1550. Eds: Carol Rawcliffe and Richard Wilson. Pub: Hambledon and London.

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1001645

- https://www.norwich.gov.uk/site/custom_scripts/citywalls/21/report.php

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/01/06/jeckyll-and-the-sunflower-motif/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglo-Ashanti_wars

- Rosemary O’Donoghue (2014). ‘Norwich, an Expanding City: 1801-1900.’ Pub: Larks Press.

- Noël Spencer (1978). Norwich Drawings. Pub: Noël Spencer and Martlet Studio.

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/cat.htm#Chafr

Thanks: I am grateful to Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk and to the George Plunkett collection for permission to use photographs.

![Eaton Park band playing in bandstand [B290] 1932-05-16.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwichdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2019/06/eaton-park-band-playing-in-bandstand-b290-1932-05-16.jpg)

![Wensum Park fountain and shelter [B155] 1931-00-00.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwichdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2019/06/wensum-park-fountain-and-shelter-b155-1931-00-00.jpg)