Tags

Bonds Norwich, Buntings Norwich, Chamberlins Norwich, Curls Norwich, Garlands Norwich, George Skipper, James Minns, Jarrolds Norwich, Woolworths Norwich

While reading about Parson Woodforde’s shopping expeditions to Norwich around 1800 [1] I was struck by the modest scale of the places he visited in the streets around the marketplace. This was still the age of the small shop run by – and generally occupied by – the shopkeeper and family, some of whom were the parson’s personal friends. The market itself offered everyday provisions: meat and fish, fruit and veg but a few yards away, separated from the everyday hurly burly of the market stalls, the genteel could stroll along the newly-paved Gentleman’s Walk and window-shop for luxury goods. Shopping had become fashionable in its own right. Displays would be seen through windows made of multiple, small panes cut from sheets of hand-blown glass. None of those shops survive in the city. Instead there are signs of the large Victorian shops and department stores that replaced them, with their huge plate glass windows.

CHAMBERLINS

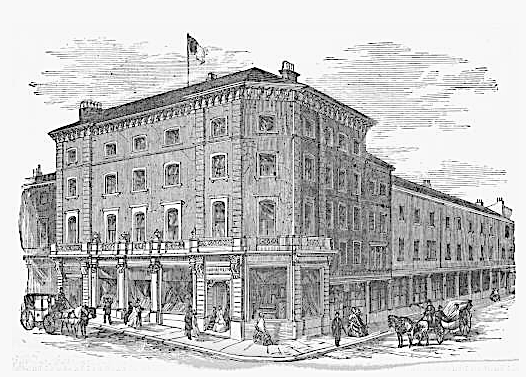

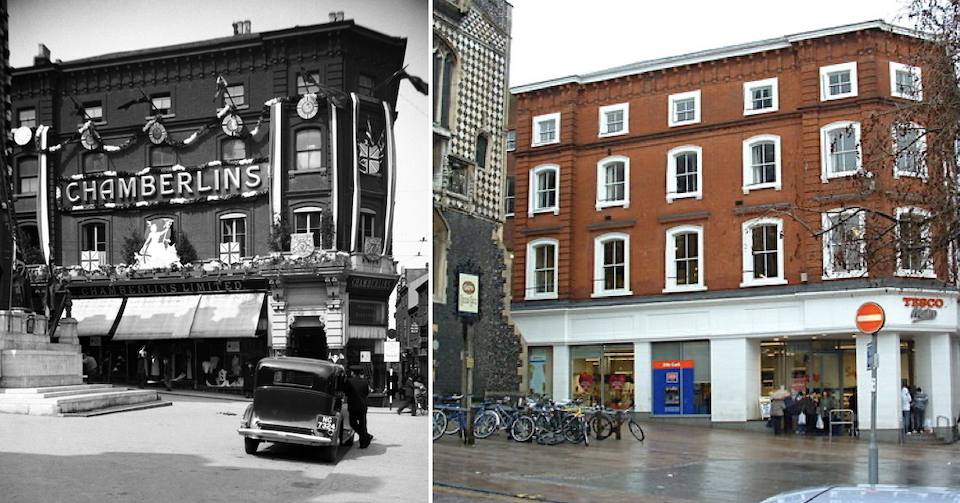

One of the largest Victorian stores around the marketplace was Chamberlins at the junction of Guildhall Hill and Dove Street. At a time when Norwich had 124 small businesses listed as ‘drapers’ [3], Chamberlins the Drapers was on a different scale, selling a wide range of soft furnishings in several departments that ran the entire length of Dove Street. Chamberlins’ also had a furnishing department that stocked ‘one of the largest assortments of carpets, linoleum, floor cloths and furniture to be sold in the Eastern Counties.’ Now, instead of window shopping in the cold and wet, the citizens of Norwich could browse in the warm and take refreshments without leaving the premises.

Another special feature of this superb establishment is the refreshment room, which is a spacious room fitted up and furnished in the most luxurious manner, and in the best possible taste. It has a buffet, well supplied by the articles in request by ladies, and the proprietors disclaim any intention of making a profit on the refreshments here supplied, the department having been provided for the convenience of the country customers, many of whom come long distances, and who fully appreciate the consideration shown for their comfort.”[3]

Chamberlins was sold to Marshall & Snelgrove in the 1950s and the corner of the site is now occupied by a Tesco Metro (due to be relocated in 2022).

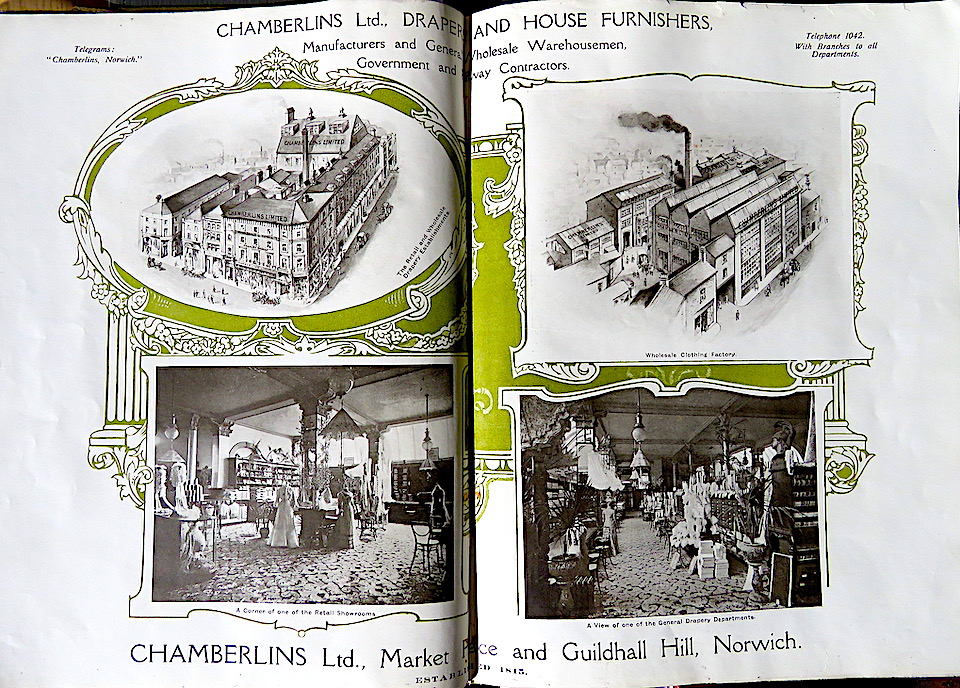

According to Mason’s Directory of 1852, Chamberlin (Henry) Sons & Co were ‘Wholesale and Retail Drapers, Market-Place’ [4]. Henry Chamberlin founded the business in 1815. His descendants became members of the local establishment: Mayor, Sheriff and Deputy-Lieutenant of Norfolk. Some idea of the extent of their enterprise can be judged from the centre spread of this 1910 trade book [5].

Chamberlins’ store was a product of the Victorian era but its factory in Botolph Street represented an excursion into modernism. Built in 1903 by AF Scott, it was described by Pevsner as the most interesting factory building in Norwich and of European importance [6]. Scott was to go on to design a department store using modern building techniques for Buntings (now M&S) in 1912 – its steel frame disguised behind a traditional exterior [7]. A vestigial Botolph Street lives on in the wasteland of Anglia Square but Chamberlins’ factory was demolished to make way for the blighted Brutalist HMSO building, Sovereign House.

The factory, which housed 800-1000 workers, was illuminated by electric lighting, proudly powered by a dynamo supplied by the Norwich firm, Laurence, Scott & Co [8]. Here, Chamberlins made a variety of clothing for the police and railways but during World War I, when they turned to war production, their entire output of waterproof clothing was requisitioned by the Admiralty [8].

In 1898, Chamberlins was devastated by a fire that started in the premises of Hurn’s, ‘the oldest rope, twine, sack and rotproof cover manufacturer in the Eastern Counties’ – established 1812 [8]. The entire Dove Street side of Chamberlins and part of its opposite side were destroyed along with their neighbour, the Norwich Public Library, set back on Guildhall Hill.

![Guildhall Hill Subscription Library [4368] 1955-08-24.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwichdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/guildhall-hill-subscription-library-4368-1955-08-24.jpg?w=635&h=958)

Hurn’s rope-making factory, with its 200-yard-long ropewalk, was in Armes Street in the suburb of Heigham but the shop where the fire started was in Dove Street at the corner with Pottergate, or so it appears from a photograph in [8].

After acquiring sites nearby, Hurns built new premises on Dove Street.

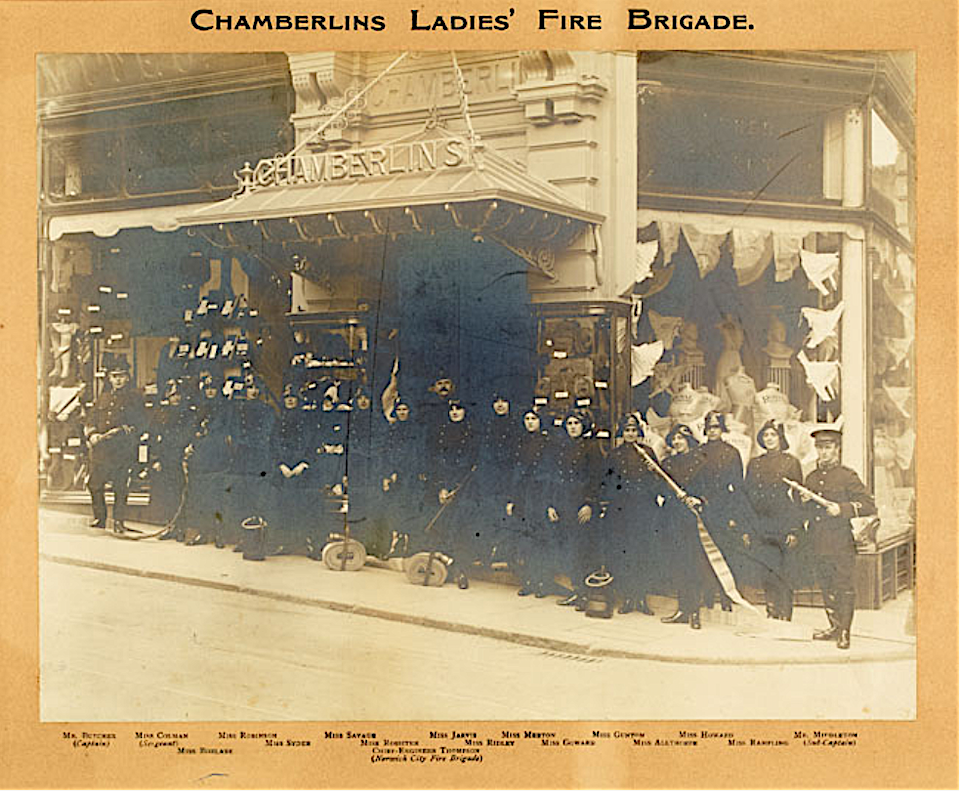

As a result of this disaster, water hydrants and hose reels were installed at the end of each floor of Chamberlins new building. Their ‘Ladies’ Fire Brigade’ is seen here during the First World War.

BUNTINGS

In 1860, Arthur Bunting set up a drapery in partnership with three Curl brothers at the corner of St Stephens Street and Rampant Horse Street, where Marks and Spencer stands today. The collaboration did not, however, last the year and the Curls set up on the opposite side of Rampant Horse Street approximately (and we’ll come to ‘approximately’) where Debenhams is located.

As drapers, Buntings sold costumes, lace, millinery, costumes, mantles (sleeveless cloaks worn over outer garments), collars, yokes, frills, ruffles. Like Chamberlins, they had a furnishing department and a tea room. They also boasted ‘what the Americans call the mail order business … (with) the aid of well-got-up catalogues.’ Despite their motto of ‘Latest, Cheapest, Best’ [5], Buntings weren’t positioning themselves at the pile-’em-high end of the market for they had a Liberty Room in which the achingly fashionable Arts and Crafts of Regent Street were offered to a provincial public.

By 1913 all this was replaced by a modern four-storey building in reinforced concrete, designed by local architect AF Scott. The new Buntings was the self-styled ‘Store for All’ where customers were soothed by an orchestral trio from 12 to 6pm daily.

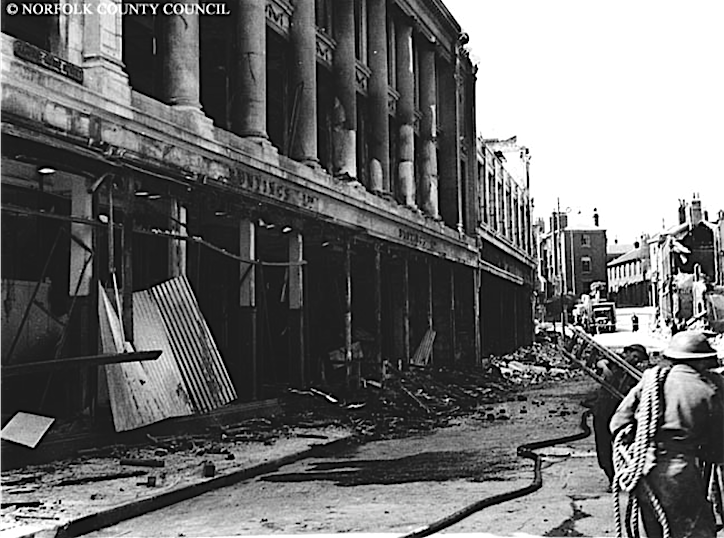

On the night of 29th April 1942, German planes dropped incendiary bombs. Three stores on Rampant Horse Street suffered heavily: Buntings, FW Woolworth & Co next door and Curl’s opposite.

Buntings was saved from total destruction by its reinforced concrete structure. It was refurbished but without the fourth storey and the corner cupola. In 1950 it was sold to Marks and Spencer. Its neighbour, Woolworths, was beyond repair as was Curl Brothers on the opposite side of Rampant Horse Street, and both were replaced with modern buildings [10].

WOOLWORTHS

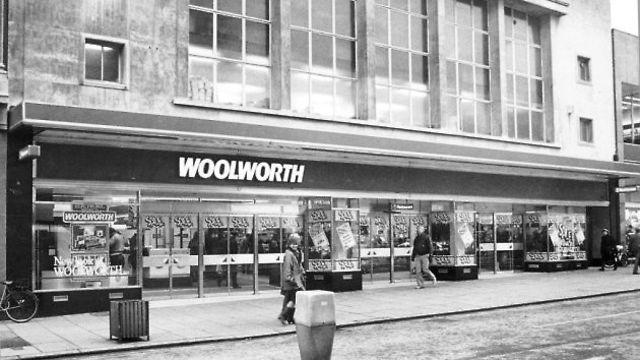

I’m not including FW Woolworth & Co as one of the big department stores: it just happened to get itself tangled up with the history of two Norwich stores on Rampant Horse Street. Woolworths was more a five and dime store (or, in this country, threepenny and sixpenny). I remember Woolies as a place to buy ‘weigh-out’ roast cashews and pick n mix sweets, and where a friend of mine shamefully bought a cover version of a Beatles record. Below, is the Woolworths building (Woolies 3) that replaced the store built adjacent to Buntings in 1929 (Woolies 2) – itself an extension of the original Woolworths store on the other side of the road (Woolies 1, see Curls below). After acquiring their neighbour in 2002, Marks and Spencer now occupy the entire west side of Rampant Horse Street, from St Stephens Street to St Stephens Church.

While the new Woolworths building on Rampant Horse Street was being built, the staff were sent to work in the Magdalen Street branch. Opened in 1934 this store was in a medieval building now occupied by Spice Valley.

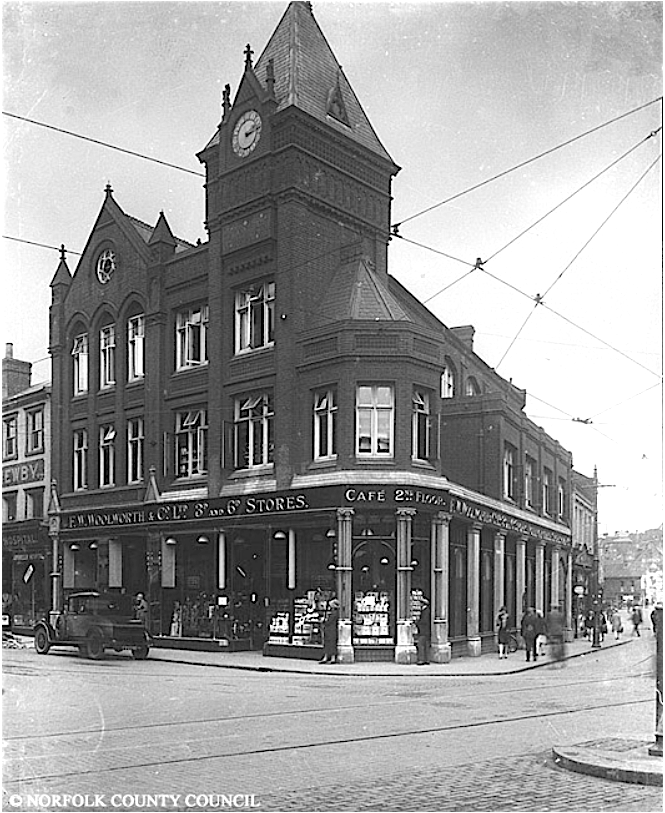

When the three Curl brothers parted company with Arthur Bunting, and moved ‘opposite’, they were unable to take over the prestigious corner site of Rampant Horse Street and Red Lion Street. As this photograph shows, it was occupied by a neo-Gothic branch of Woolworths that opened for business in 1914 – the first of three Woolies on this street.

CURLS

By the time of King George V’s Silver Jubilee in 1935, Woolworths were no longer located in the corner building (right). Instead, they had moved in 1929 to larger premises on the opposite side of Rampant Horse Street, adjacent to Buntings. This was to be the branch of Woolies destroyed in WWII (arrowed). Saxone shoes and an insurance company now occupied the corner spot. So, could those be the awnings of Curls department store further down the street?

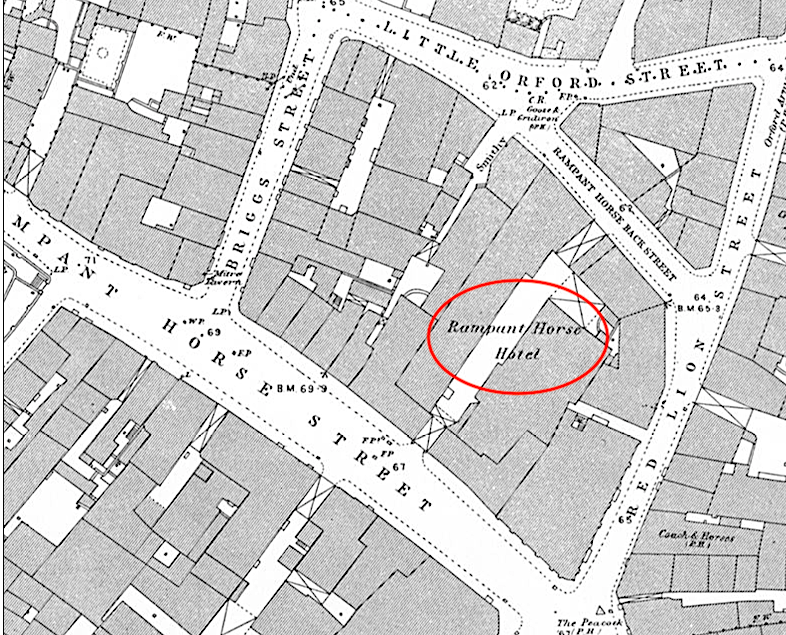

Curls had bought a range of buildings including the old Rampant Horse Hotel that had been known as far back as the C13 as The Ramping Horse [8]. We have encountered this old inn several times. William Unthank (d.1800), the forefather of the Norwich Unthanks, was a peruke (wig) maker; he also owned coaches for hire. His address was given as Nos 2 and 3 Rampant Horse Street and, since the Ipswich coach left from the inn, it might possibly have been his [11].

Curls had departments for china, glassware, furniture, millinery (hats), costumes, wallpaper, dressmaking etc. The Outfits Department was in the former billiard room of the Rampant Horse Hotel. Curls employed over 500 staff, including those at their factory in Pottergate [8].

Ironically, in a city whose once pre-eminent woollen textile trade was finished off by competition from the north, Curls had a Manchester Department that sold cotton products like flannelette and shirt material. The victory of cotton over wool was won in northern power mills centred around Manchester. For centuries, Norwich woollen and silk fabrics had been produced on hand looms but by the late eighteenth/early nineteenth century the city had been too slow to mechanise and confront the challenge. Although the lighter materials manufactured in ’Cottonopolis’ were highly popular with the public, their success was to a significant extent subsidised by the slaves who picked the cotton (imported via Liverpool) in the plantations of the West Indies and the southern states of America.

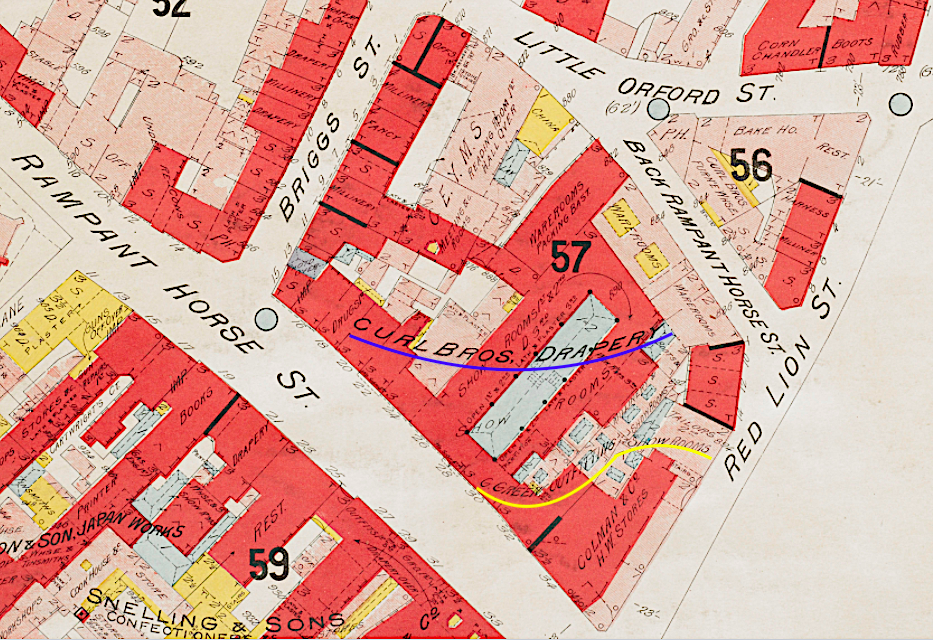

A fire insurance map* provides greater detail of the layout of the site in 1894. At this stage it is clear that Curls occupied only part of Rampant Horse Street, sharing that side of the block with Green’s the Outfitters (before they moved opposite Orford Hill), while the corner with Red Lion Street housed Colman & Co hardware shop. The Brigg Street facade, however, contains departments labelled ‘Millinery’ and ‘Fancy’ and would therefore seem to belong entirely to Curls. Surrounded by Curls is the CEYMS reading room. As part of the postwar rebuilding Brigg Street was widened and the initials of the Church of England Young Men’s Society are still to be seen on the side of the postwar building that superseded Curls.

* Charles E Goad Ltd produced detailed fire maps of most of the country and there are several sheets devoted to Norwich. At a time when high density commercial buildings and industrial processes were intermixed these maps provided important information on construction materials, water supplies/hydrants and neighbouring buildings. Every department store mentioned in this post has been been affected by fire.

This map just missed the great change to the east end of the store when, in 1902, the Curl brothers remodelled much of the shop and built a new extension along Orford Place [8].

All of this was to change during the Baedeker raids of 1942.

For several years after the war, the block that once was Curls was just a (very large) hole in the ground, used as a car park and a water cistern [12]. In a remarkable act of familial cooperation, Jarrolds department store in London Street let Curls (to whom they were related by marriage) occupy the first floor of their London/Exchange Street premises. Curls then moved into property provided by Norwich Union for burnt-out businesses where they traded as ‘Curls of Westlegate’. Here, they sold children’s and ladies fashions, millinery and drapery while their furniture department remained at Exchange Street. Curls had to wait until 1956 for all departments to be reunited in the new store that had arisen on their bomb-damaged site. This steel-framed building, which Pevsner and Wilson judged to be ‘rather too bland … for its position‘[6], was designed by Wilfred Boning Scott(1858-1981), one of AF Scott’s two sons who followed him into the business. In the 1960s the department store was sold to Debenhams but continued trading as Curls until 1973.

Garlands

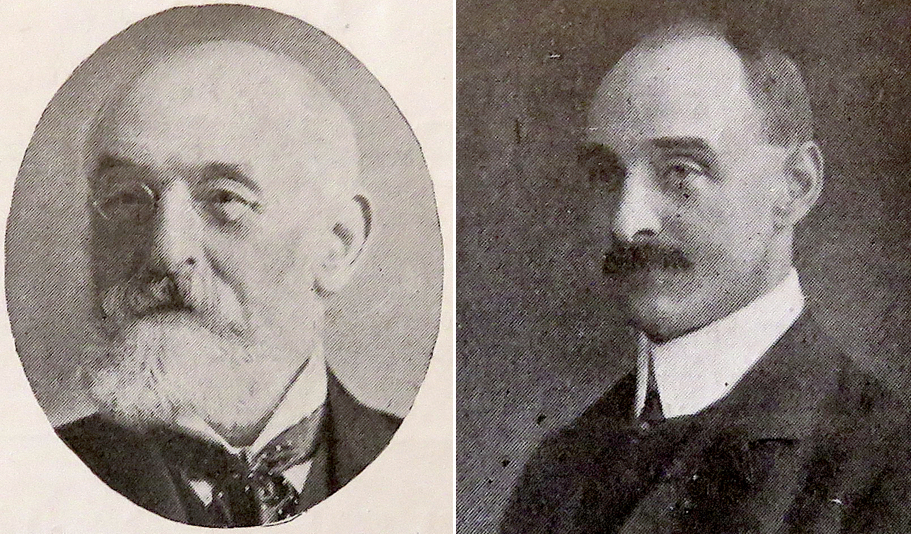

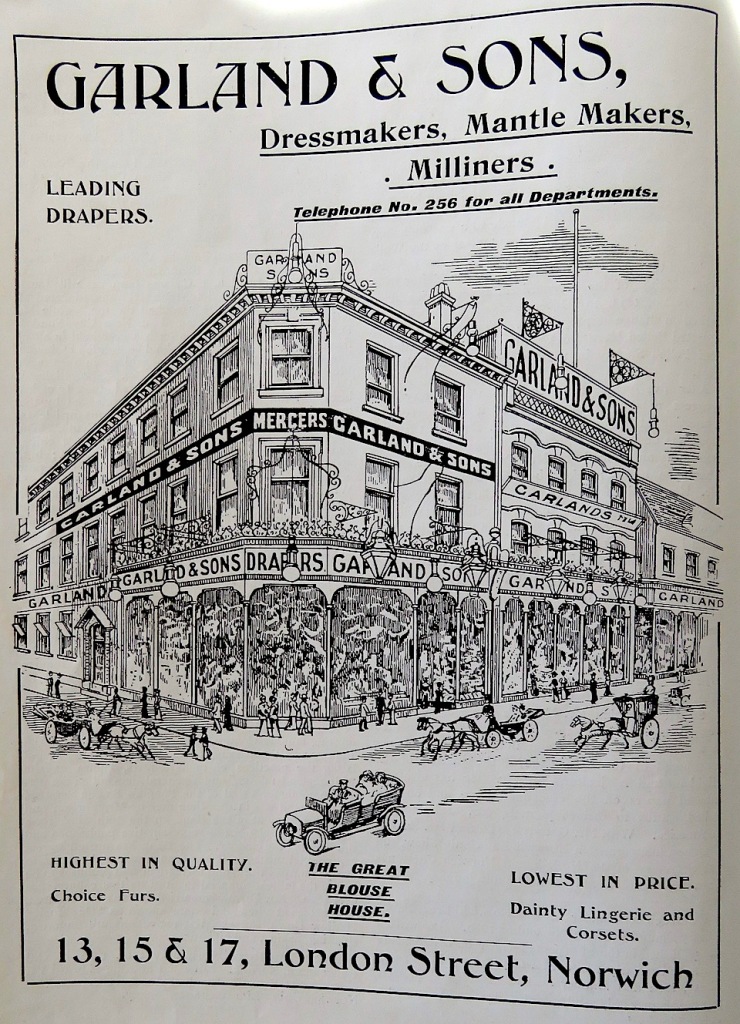

Richard Ellery Garland, born in Stroud, opened his own store in London Street, Norwich, in 1862 [5].

At 15, Richard Garland had been an apprentice draper in the London area. His own store in Norwich was to specialise in drapery but we see from this advertisement that Garlands were also dressmakers, mantle makers and milliners who sold ‘choice furs’, ‘dainty lingerie’ and corsets.

By 1920 it had become a store with nearly 30 departments. The central bay of the London Street facade was very much as it appeared in the early 1900s but the Little London Street facade and the corner had been modernised.

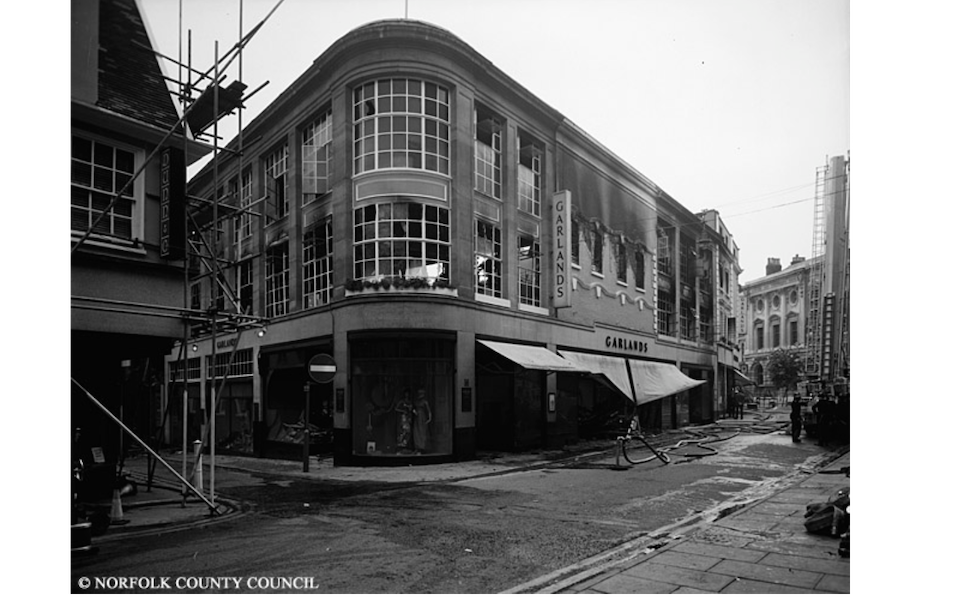

In 1970, a chip pan fire in the kitchens spread to destroy the store, taking almost 70 firefighters three hours to get the fire under control [13]. Jarrolds pensioners can still remember being on the roof of the neighbouring Jarrolds Department Store, putting out sparks from the Garlands fire.

Garlands was rebuilt in 1973 – its ‘castle-like sheer walls’ supported by a colonnade that provided covered access to the ground floor shops. Pevsner and Wilson [6] saw it as a ‘respectable attempt to introduce a modernist element‘. Garlands closed in 1984. The following year it reopened as Habitat, which occupied the upper floor until its closure in 2011.

BONDS

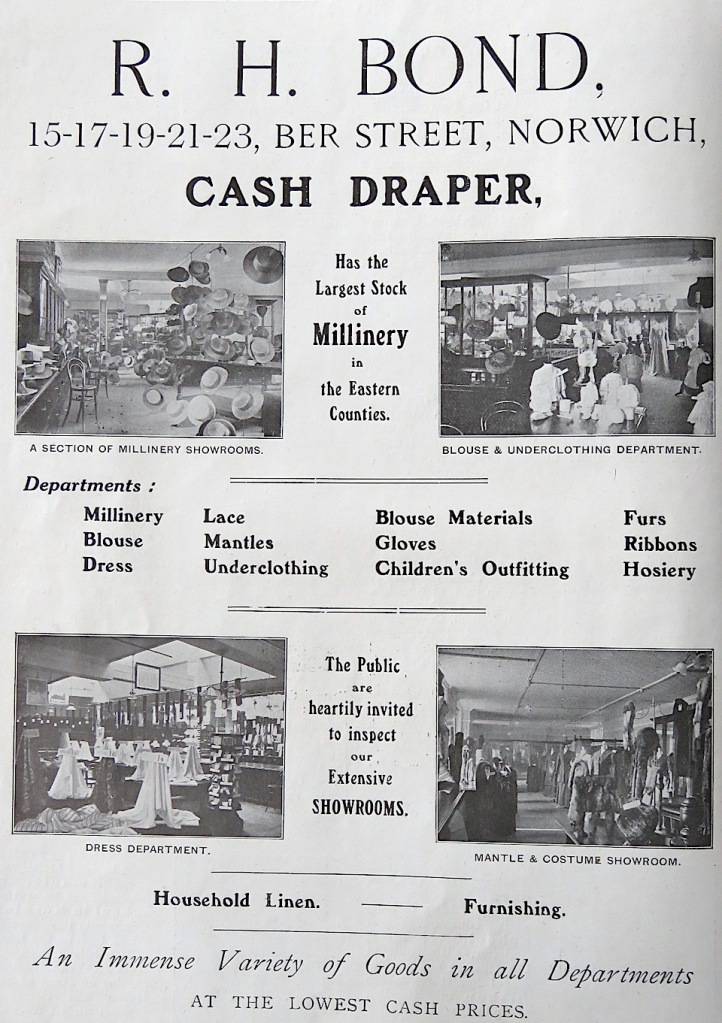

In 1879, Robert Herne Bond (b 1844) from Ludham in The Broads, started his business in Ber Street, Norwich, as a ‘Cash Draper’.

He sold the now familiar stock of mantles, blouse materials, furs, ribbons etc etc, except he differentiated himself from his rivals by claiming the largest stock of millinery in the eastern counties. According to their advertisements, all the large drapers in the city focused on soft furnishings for the house and clothing for women and children. Men were catered for elsewhere, perhaps in tailor shops, of which there were 83 in 1852 [4].

According to George Plunkett, in the late C19 a Major Crow owned 2-3 cottages on All Saints Green that he restored and converted to the Thatched Assembly Rooms. In 1915 it opened as The Thatched cinema before becoming Robert Bond’s ballroom and furnishing hall. Bond now owned properties that extended from Ber Street through to All Saints Green.

Bonds was bombed in June 1942.

After the war, Robert Bond’s son J Owen Bond, who had worked with George Skipper, designed a new store for his father. In 1982 it began trading as part of the John Lewis Partnership.

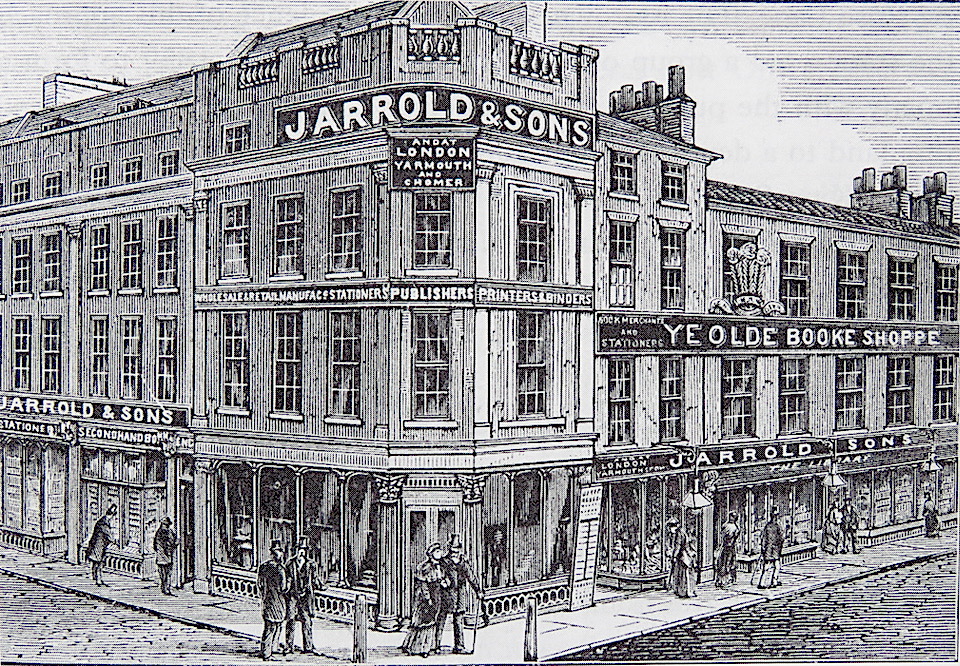

JARROLDS

London Street, which was originally known as Cockey Lane and London Lane, was a narrow medieval thoroughfare where pedestrians had to duck into doorways to avoid being crushed by carts [14]. There had been talk about widening it since at least the late C18 but this only happened in a piecemeal fashion: first in the mid C19 when the arrival of the railway created demand for better access to the market from Thorpe Station, then with Edward Boardman’s scheme of 1876 at the Gentleman’s Walk end [6]. By the time London Street had become the first pedestrianized street in the country (1967), Jarrolds – on the opposite side of the street – was the only original business remaining [6].

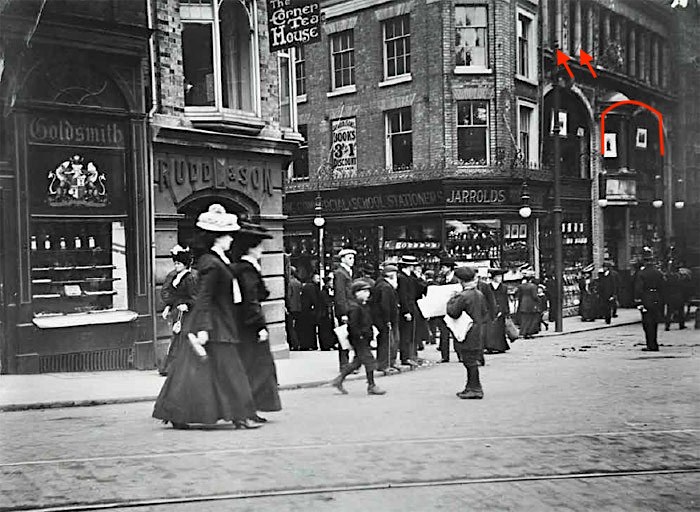

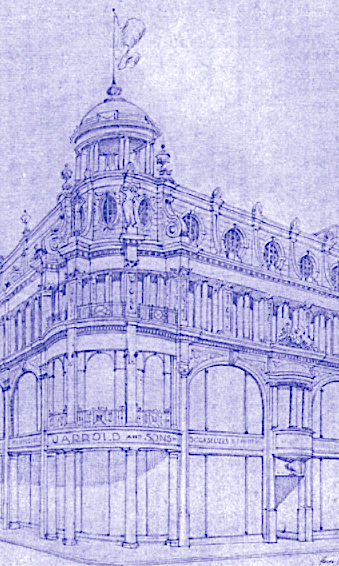

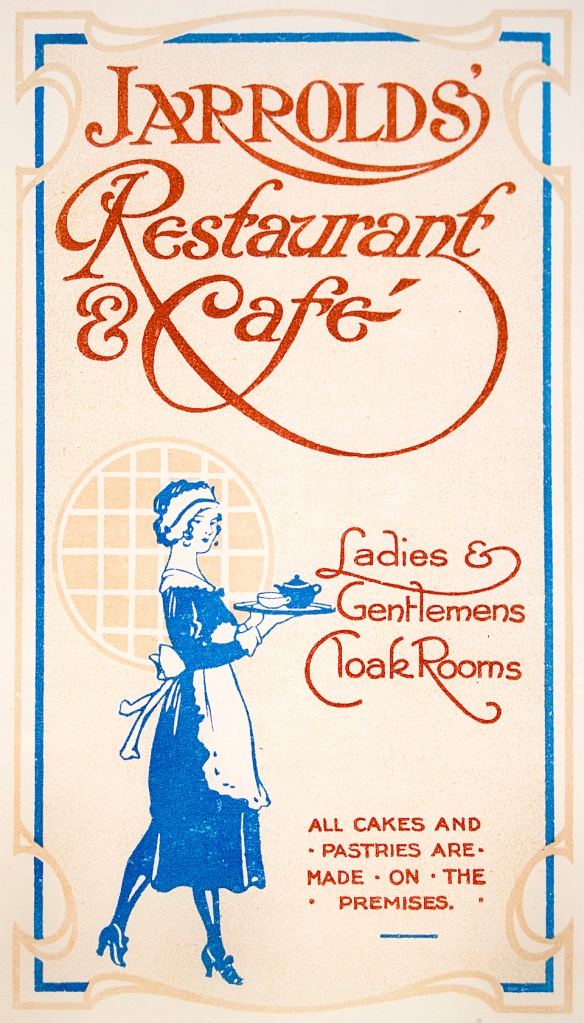

Jarrolds began life in 1770, in Woodbridge, Suffolk where 25-year-old John Jarrold opened up as a ‘Grocer, Linnen and Woollen-Draper’ in the marketplace [15]. In 1823 his son, also John Jarrold, came to Norwich. He announced in the Norwich Mercury that he and his eldest son John James were open for business in the city as ‘Printers, Booksellers, Binders and Stationers.’ This was on the Gentlemans Walk side of London Street, which was known at that time as Cockey Lane, after the cockey or stream that ran beneath the street. In 1840, John Jarrold and his four sons moved across the street to the present location. The illustration above shows that publishing and selling books remained their main business at the end of the century, detached from the fierce competition between the other large stores who focussed on drapery and millinery etc.

In 1896 the celebrated Norwich architect George Skipper was employing around 50 staff. His offices in Opie Street were now too small so he moved to 7 London Street where he became a neighbour to Jarrold & Sons. In 1903-5, Skipper remodelled the store and some of the changes to the London Street facade can be seen below.

Inside the new-look Jarrolds, circa 1907.

Jarrolds today, in the free Neo-Classical style designed by George Skipper.

The semicircular bay above the main entrance anchors the store to the corner of the marketplace. The facade has been compared to a tiered wedding cake but is not topped off as Skipper had imagined. The architect had proposed a signature copper cupola [16] but in this case the clients refused to indulge him.

The Exchange Street facade had to wait until 1923 for Skipper to complete the modernisation he had begun in London Street. The remainder of the block, down to Bedford Street, was at that time occupied by the Corn Exchange.

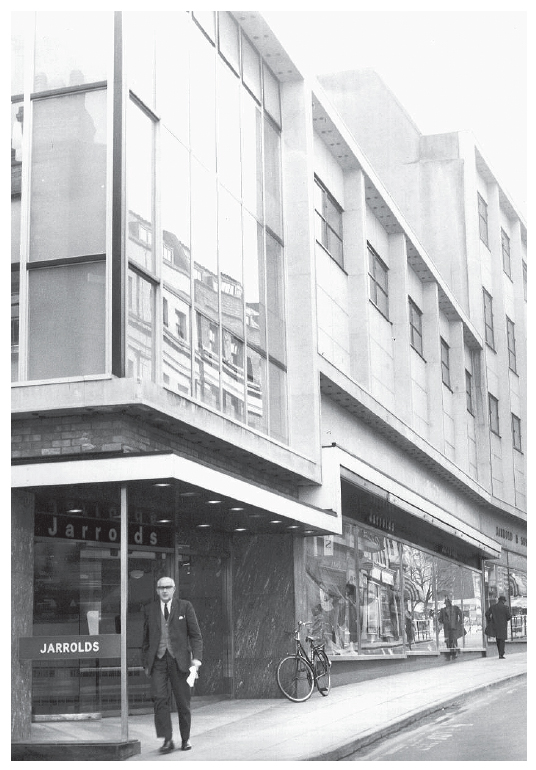

In 1964, Jarrolds increased the size of the store when they bought the Corn Exchange and rebuilt on the site.

One of the most distinctive features of the Jarrolds building is the carved brickwork on Skipper’s former offices. Although architects were not allowed to advertise their practice, Skipper commissioned Guntons brickyard in Costessey to carve six fired clay panels celebrating his work. Look up next time you walk down London Street.

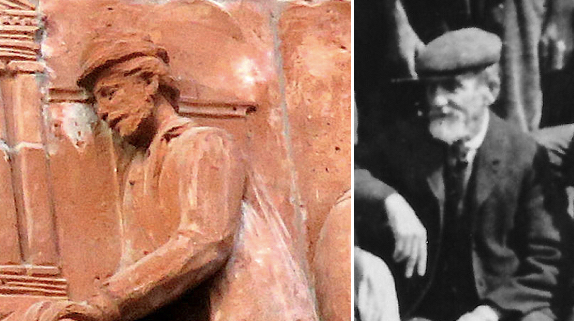

Regular readers may remember a previous post in which I described the character holding up the shield for Skipper’s inspection. Having just been sent a photograph of the shy Guntons’ carver, James Minns, I suggested that the terracotta carving represented Minns himself [16].

The head was a reasonable likeness of James Minns but the body was awkward and the large panel less convincing than its partner: heavy 3D modelling instead of low relief. In a further post, devoted to Minns’ life and work, I raised the possibility that this could have been an effect of the ‘senile decay’ given as one of the causes of his death in 1904 [17]. In his recent book on Skipper, Richard Barnes provides a further twist [18]. He cites Faith Shaw’s 1971 dissertation in which she mentions discussing the panels with one of Skipper’s foremen who recalled how, ‘everyone in the (Skipper) office shared in the carving.’ If, as it seems, the panels weren’t installed until 1903-4 it might explain why hands other than Minns’ were at work on the Cosseyware panels.

© Reggie Unthank 2021

Sources

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2020/11/15/parson-woodforde-goes-to-market/

- A Comprehensive History of Norwich 1869. Available online at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/44568/44568-h/44568-h.htm#page621

- https://www.norfolkchamber.co.uk/about/history/sectors/retail/chamberlin-sons

- https://www.gutenberg.org/files/62401/62401-h/62401-h.htm

- Citizens of No Mean City (1910). Jarrold & Sons, Norwich

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (2002). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2020/08/15/twentieth-century-norwich-buildings/

- Edward Burgess and Wilfred E Burgess (1904, reprinted 2014). The Men Who Have Made Norwich. Pub: Norfolk Industrial Archaeology Society.

- https://www.norfolkchamber.co.uk/about/history/sectors/retail/buntings

- https://wooliesbuildings.wordpress.com/2018/05/10/norwich-store-44/

- A.J.Nixseaman (1972). The Intwood Story. Private imprint.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curl_Brothers

- https://www.edp24.co.uk/lifestyle/why-august-1-is-a-date-of-tragedy-over-the-1574906

- Rosemary O’Donoghue (2014). Norwich, an Expanding City. Pub: Larks Press.

- Pete Goodrum (2019). Jarrold 250 Years: A History. Pub: Jarrold & Sons Ltd. Can be bought online at: https://www.jarrold.co.uk/departments/books/local-books/jarrold-250-years-a-history-by-pete-goodrum

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/02/15/the-flamboyant-mr-skipper/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2020/03/15/james-minns-carver/

- Richard Barnes (2020). George Skipper: The Architect’s Life and Works.’ Pub: Frontier Publishing.

Thanks. I am grateful to Caroline Jarrold for providing photographs of the store. My thanks also to Rosemary Dixon of Archant and Thomas Barnes, Assistant Archivist at Aviva.

This is a fascinating article and it reminded me of a story in my family’s history.

My grandmother ,then Sarah Chilvers, was a ladies maid for the Dawson Paul family who lived in the house that is now the High school for Girls in Newmarket Rd.

She was engaged for seven years to a young man,an amateur artist, who was the proud possessor of one of the first bicycle s in Norwich.

One day he was cycling full pelt down Guildhall Hill. His brake s failed and he crashed into one of Jarrold’s windows. Tragically he never recovered . His brain damage was so severe that he spent the rest of his life in a mental institution.

My Grandmother was heartbroken but eventually moved to London and married.

LikeLike

Dear Clare, How tragic. It is tempting to go fast down Guildhall Hill and I occasionally see pedestrians stranded in the middle of the road, not sure how to dodge the cyclists. By the way, the HSG house was once occupied by Sir Charles Gilman who had moved from Colonel Unthank’s Heigham House on Unthank Road. Reggie.

LikeLike

Well up to your usual high standard – I well remember the lost stores, Chamberlins, Garlands and Buntings. My mother was a dressmaker and I seemed to spend a great deal of time as a young child in those stores, especially Buntings which after 1942 occupied a site next to Garlands in London Street, about where Mountain Warehouse is today. For those of us who came into the city via Botolph Street, Frank Price’s was very convenient, both as a store and also as a short cut into Magdalen Street.

Another favourite store when I was a teenager was Willmotts on Prince of Wales Road which was one of the very few places where you could here the current ‘pop’ records – the BBC played very few and Radio Luxembourg didn’t always come through on our antiquated radios, even if we were allowed to try to tune in to it! Another world!

Hope Bros, Greens and Rumsey Wells were for school uniforms, Rumsey Wells being the acme (a very quirky acme at that) with a wonderful contrivance for measuring your hat size

Don Watson

LikeLike

I didn’t realise that Buntings moved to London Street. Greens and Rumsey Wells were on the list but I ran out of space. The emphasis on female customers in the large drapery stores is inescapable; can you remember where men bought their clothing, Don?

LikeLike

Good question. Probably many men (and women) would have gone to the other omission from your list – the Co-op in St Stephens. For my mother, like many people, the divi was important. Of course Burton’s, John Collier and Alexandre’s supplied the suits which were required wear at the Norwich Union and in all the banks, Austin Reed if you wanted to spend a bit more.

Don Watson

LikeLike

Wonderful as usual!

LikeLike

Thank you Heather. Let’s hope that we’re not seeing another kind of climate change in which we lose some of the large department stores. There has to be more than online retail.

LikeLike

Thanks, Reggie, for another fascinating article and set of photographs, plans and illustrations.

Many of these shops were an important part of the identity of Norwich for a child growing up in the city 60 – 70 years ago. I particularly recall the transformation of the massive bomb-damage hole in Rampant Horse Street into the new Curls building, with a bright yellow flag flying above, and inside the store what I believe was Norwich’s first escalator – a cause of much excitement to my young self.

I was slightly surprised to see the building on Guildhall Hill (labelled Subscription Library) described as the Public Library. I always thought that to be the building on the corner of Duke Street and St Andrews Street, built some 20 years after the one in your illustration (and I think the first-ever purpose built public library: it used to say ‘Free Library’ over the front door) – a regular destination for me and my sister before the opening of David Percival’s new library building near the City Hall.

LikeLike

Hello Richard. The history of Norwich ‘public’ and ‘free’ libraries is tangled. What had been Norwich Public Library moved to the site of the old gaol on Guildhall Hill in 1838. In 1850 the Libraries Act allowed the council – as you mentioned – to construct the first purpose-built and truly free (ie, non-subscription) library at the corner of Duke and St Andrews Streets, but other libraries remained open. There’s a tour through this labyrinth in https://wp.me/p71GjT-8MZ. Reggie

LikeLike

Another great read, thank you

LikeLike

Thank you for the kind comment Paul.

LikeLike

Fascinating article, as always. I grew up in Norwich. As a young child I loved going to Woolworths to spend my pocket money on cheap but alluringly glittery plastic jewellery. As teenagers my friends and I would spend entire Saturday afternoons eking out milkshakes in the cafe at Peter Robinson (before it became Top Shop). Then we’d all migrate downstairs or over to Curls to find something to wear for Saturday evening – which usually started at the Trowel & Hammer – even though most of us were too young to drink alcohol.

LikeLike

I’m sure this pattern was repeated around the country, Kate. My earliest, and unhappiest, memory of Woolies from another town was when when my father refused to give me the ‘free’ chocolate that I could just about read on a banner. I couldn’t understand his explanation that he’d have to spend a lot of money to get it.

LikeLike

Pingback: AF Scott, Architect:conservative or pioneer? | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Hi. I was researching the history of these stores as part of looking at the department stores of the UK. I have recently found that by 1949 Debenhams actually controlled many of the stores discussed here. Curl Brothers had been bought by Footman, Pretty of Ipswich sometime during the latest 20s (Listing Statements of the New York Stock Exchange. Vol. 53. 1928. p. 2), who were at the time controlled the Drapery Trust, whom Debenhams acquired in 1927. Garlands was purchased at some point before 1949, when they purchased Chamberlins (via subsidiary Marshall & Snellgrove) and Buntings (Debenhams”. Leathergoods. Vol. 66. 1949. p. 74.). I know that Buntings is next door to Garlands, but I believe it may have been merged into Garlands, as these pictures before the 1970 fire show Buntings at the end of the building and then not there, being part of Garlands. https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/1150388298539347851/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear David, I was unaware that Buntings had a presence in the ‘Garlands’ block between Little London Lane (back of Jarrolds) and Swan Lane but the two photos clearly show this to have been the case. As for ownership, Norwich Union is known to have found space for bomb-damaged businesses after the war and Jarrold’s found space for Curls on their own premises. Might something like this account for Buntings presence at the corner of Swan Lane? Kind regards, Reggie

LikeLike

I have found further information from The 1927 dictionary of Directory of Directors (https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=VRMtAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA222&dq=%22chamberlins%22+norwich&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&source=gb_mobile_search&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi5hMGzqvr9AhWWaMAKHSN-D28Q6AF6BAgJEAM#v=onepage&q=%22chamberlins%22%20norwich&f=false) that Charles and John Bunting were actually directors of Chamberlins. I then found this (https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=CU4MAQAAMAAJ&q=%22chamberlins%22+buntings+norwich&dq=%22chamberlins%22+buntings+norwich&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&source=gb_mobile_search&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwibq4ap_Pv9AhUJQ8AKHYgkCJQQ6AF6BAgDEAM#%22chamberlins%22%20buntings%20norwich) The Stock Exchange Official Year-book of 1944 which confirms that Chamberlins actually controlled Buntings, though can’t find any further information to confirm if this was a merger or takeover. As to Buntings, I found that they had moved to London Road via this link(https://www.flickr.com/photos/spixworth/4070889413) before finding the picture confirming this, which said in the comments that both businesses had been destroyed by the fire. I now seriously doubt this, and that Buntings were just merged into Garlands after they were purchased by Debenhams as part of rationalisation, based upon the pictures, and that in Bearmans Financial Year Book of Europe 1968 (https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=kRi0AAAAIAAJ&q=chamberlins+curl+norwich+wholesale&dq=chamberlins+curl+norwich+wholesale&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&source=gb_mobile_search&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj824_x_fv9AhXBg1wKHUMdAp8Q6AF6BAgEEAM#wholesale) lists Curls & Chamberlins (wholesale) Ltd as an arm of Debenhams, showing these two businesses had been merged.

LikeLike

Thank you for the update David.

LikeLike