In these covid times I cycle. Along the celestial Unthank Road to the junction with Newmarket Road, down the hill to Eaton and out to open countryside. Before the crossing is a house with two intriguing names carved in stone on the gate pillars. The first is badly spalled and its few remaining letters … CRO … would be unknowable except for a modern house-plate, Hillcroft. Although a few of its letters are obscured the other sign can only be for the Royal Norfolk Nurseries.

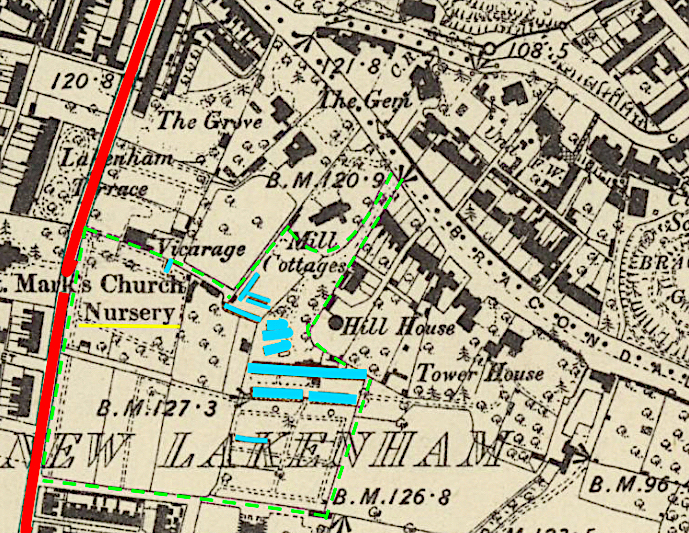

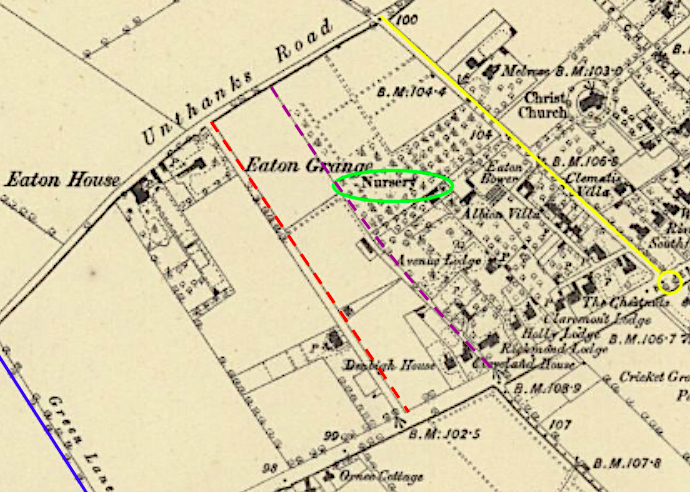

I was curious to look into this because for several years I’d wondered about the clear, unbuilt-upon spaces on the early maps marked ‘nursery ground’ or ‘garden ground’. The OS map of 1879-86 shows that the Royal Norfolk Nurseries occupied sites from the junction with Unthank Road (yellow) down the hill to Bluebell Road (blue) and a larger area between Bluebell Road and the river, now in the shadow of the A11 Eaton flyover/bypass (green).

Much of the land, from the Unthank’s estate east of Mount Pleasant in Norwich [1] down to Eaton, was owned by the Dean and Chapter of Norwich Cathedral; this applied to the village itself with the notable exception of a few oases, including the 12 and 17 acre plots owned by the Corporation of Eaton.

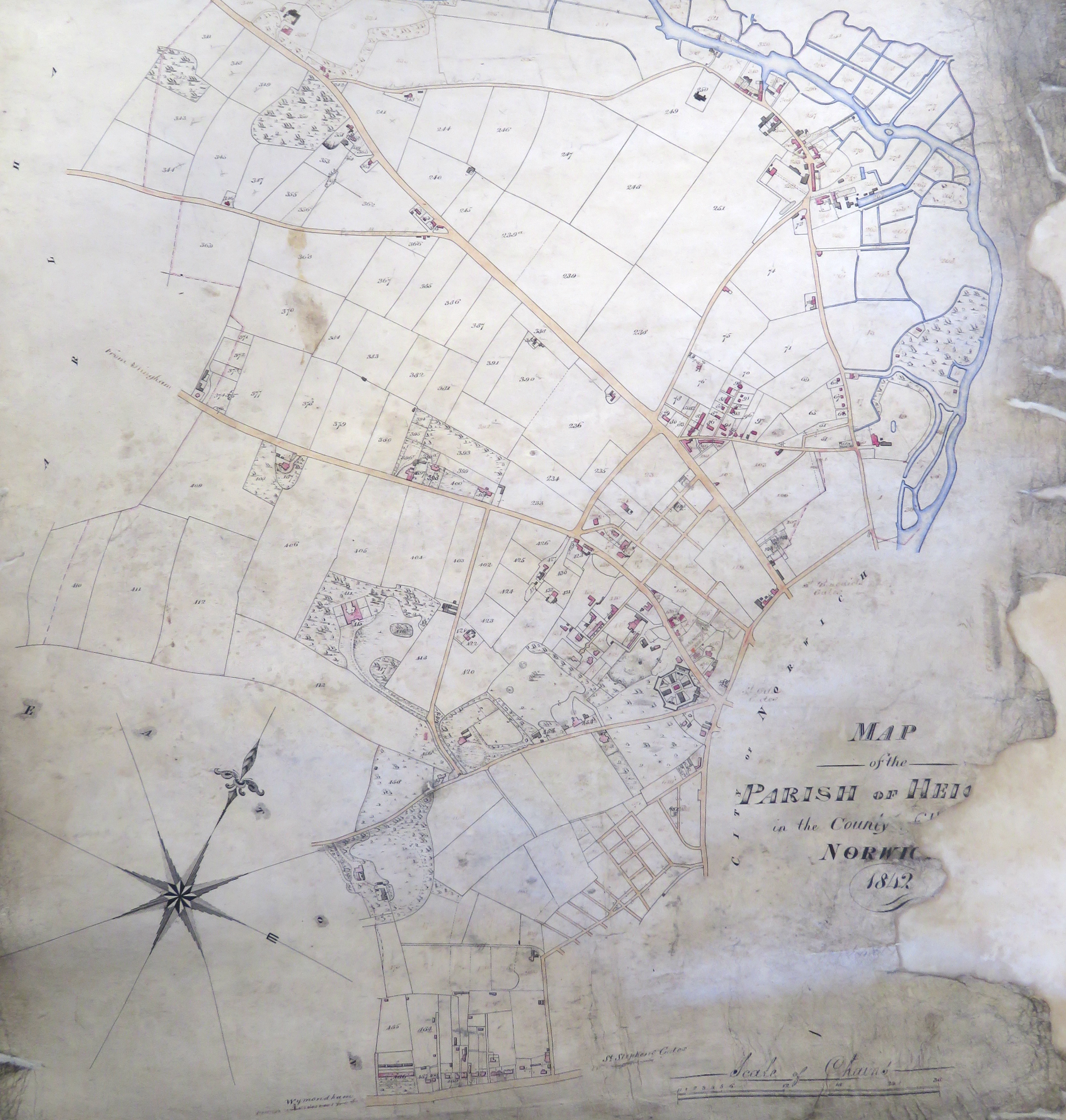

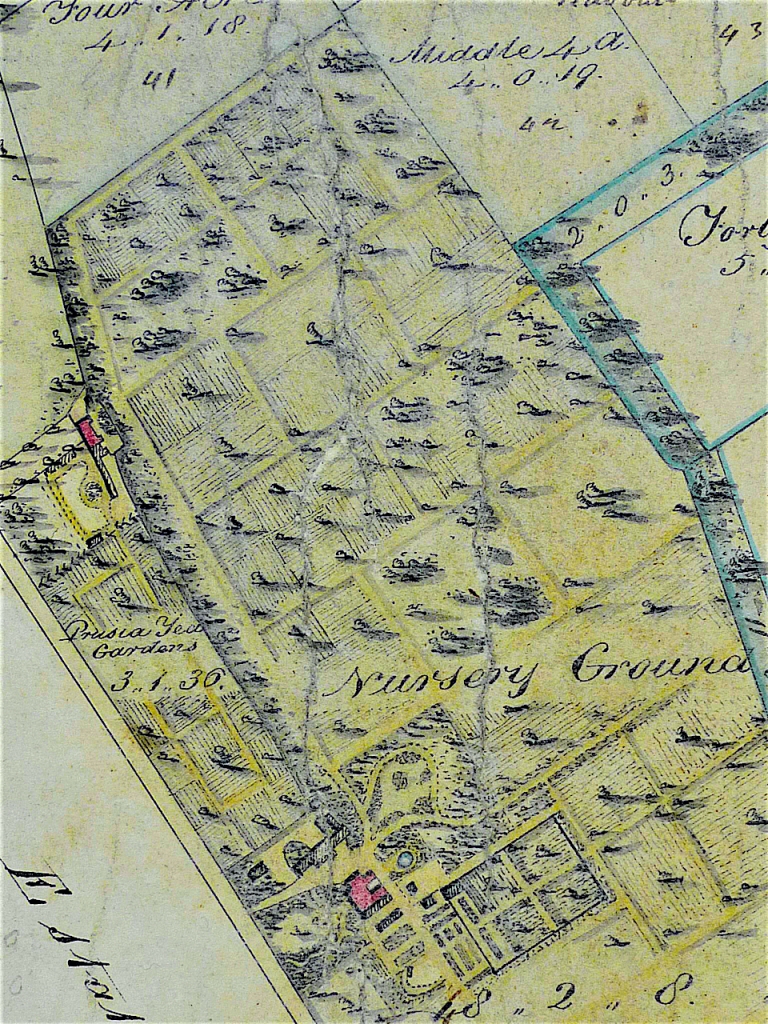

The 1838 tithe map and accompanying apportionment record (1839) gives the name of landowners liable to pay church tithes and, within the two outlined areas, William Creasey Ewing (1787-1862) owned most of the individual numbered plots.

The son of William Creasey Ewing, John William Ewing (1815-1868), evidently inherited the land from his father and is listed as Nurseryman, Florist, Lime burner (and there is a lime pit on the site) and Seedsman [2].

Below is The Old House, Church Lane, Eaton (formerly known as Shrublands) where William Creasey Ewing lived. The National Census records his son John William living there in 1851 [2].

Prior to this census return, John William Ewing lived in Shepherd’s House near Mackie’s, the city’s long-established and foremost nursery, founded in the 1700s on Ipswich Road [1]. We’ll come to Mackie’s shortly.

Between 1833 and 1840, John William Ewing and Frederick Mackie entered into a partnership, forming Mackie and Ewing’s Nurseries, but in 1845 the partnership was dissolved. A newspaper advertisement to this effect places JW Ewing in Ewing’s Nursery at Eaton, indicating that JW Ewing was managing the nursery when he was 30, if not before.

A year later, (incidentally the year his son and successor was born) an invoice from JW Ewing, Nurseryman and Seedsman, shows that the Eaton Nursery was selling ‘Forest & Fruit Trees, Flowering Shrubs etc’ and, in smaller script, ‘Garden & Agricultural Seeds, Dutch Bulbs, Russian Mats (anyone?)*, Mushroom spawn etc.’ *(A reader, Lyn, provided the answer. Russian Mats, exported via the port of Archangel, were closely woven from the leaves of aquatic plants and used to protect fruit trees and young plants etc).

When he died, Ewing’s Royal Norfolk Nurseries were inherited by his son, John Edward Ewing (1846-1933), but when John left Norwich in 1893/4 the business at Eaton was lost.

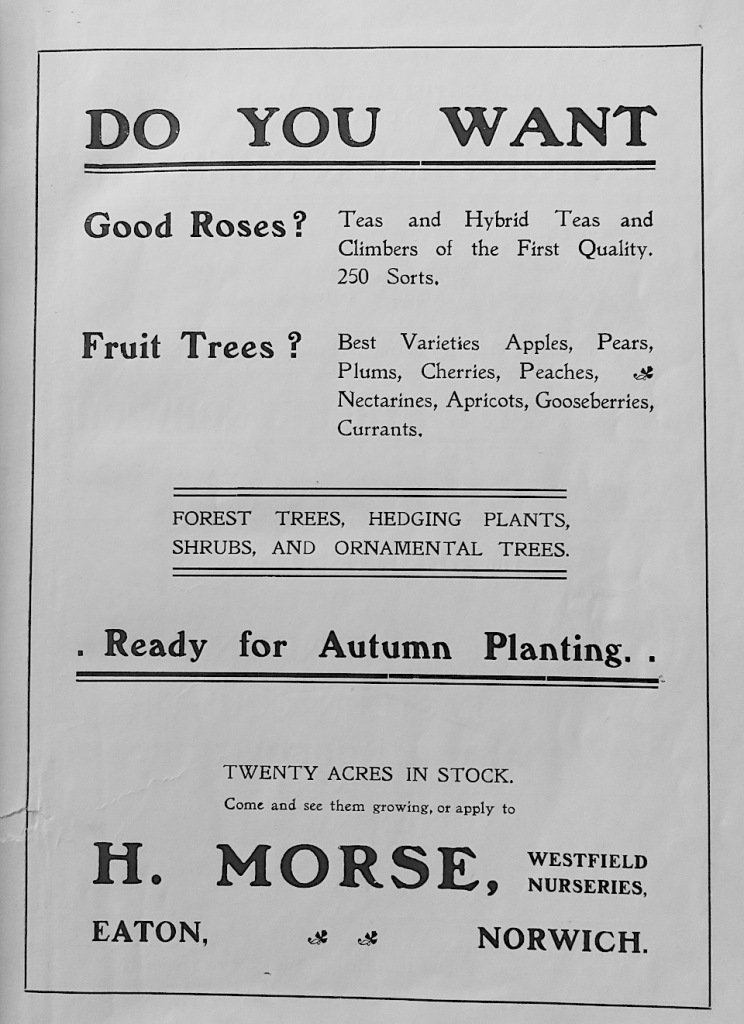

In his History of the Parish of Eaton (1917), Walter Rye wrote that ‘the chief trade of the village is now growing fruit trees and roses for the market’ [3]. He went on to say that other well known Eaton nurseries are the three rose nurseries of C Morse, E Morse and RG Morse and the ‘old-established nursery of Mr Hussey in the Mile End Road.’

Ernest Morse appears in this 1910 book of local worthies and businessmen [4] advertising himself as a grower of fruit, cucumbers and grapes. His older brother Henry took out a full page advert announcing his 20 acres of rose bushes and fruit trees in the Westfield Nurseries, Eaton.

John Ewing’s partnership with Mackie’s was dissolved in 1845, leaving Mackie’s to stand alone as the city’s predominant nurserymen.

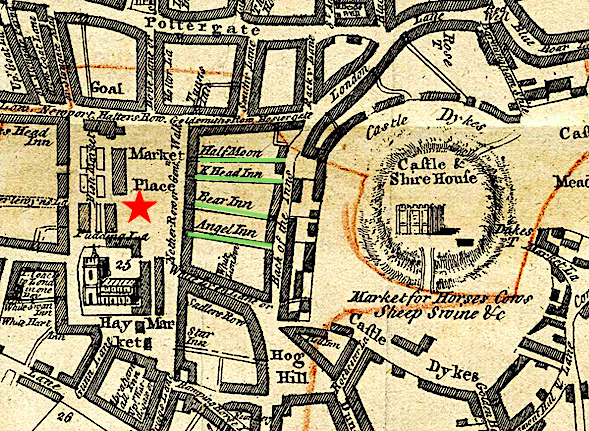

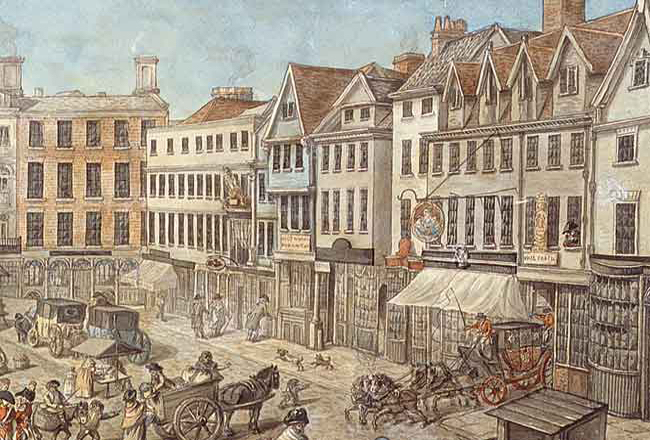

The industrial scale of Mackie’s operations made it one of the largest provincial nurseries [5, 6]. Bryant’s 1826 map (above) shows Mackie’s 100 acre site was situated around the crossroads where present-day Daniels Road intersects Ipswich Road but the business can be traced back to John Baldrey’s nursery in the city where, around 1750, he was selling plants and trees on a wholesale basis. In 1759, this was taken over by the Aram family – who were selling ‘Scotch firs’ at ten shillings per thousand – and in 1777 John Mackie joined the business. This was around the time the nursery moved to what, in its final days, was to be known as ‘the Daniels Road’ site.

Parson Woodforde knew Mackie:

“Mackay, Gardener at Norwich, called here (the parsonage at Weston Longville) this Even’, and he walked over my garden with me and then went away. He told me how to preserve my Fruit Trees etc. from being inj’ured for the future by the ants, which was to wash them well with soap sudds after our general washing, especially in the Winter.”(from Parson Woodforde’s diary, July 13 1781).

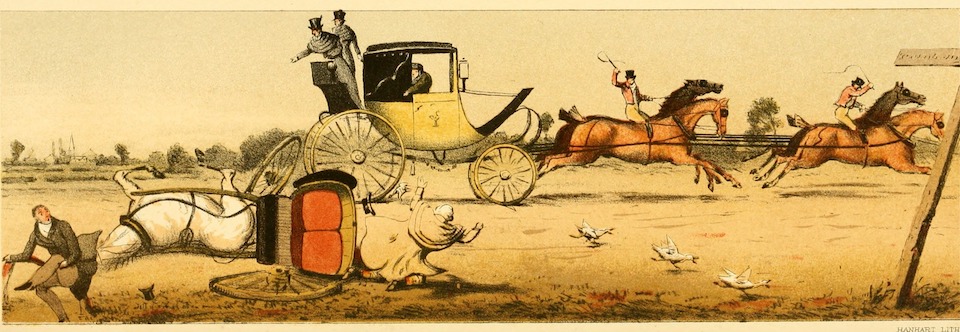

As Louise Crawley describes in her essay on the Norwich Nurserymen, Mackie’s site was so extensive that clients recorded being driven around it by carriage [6]. Mackie’s was to remain in the family for four generations until it was sold in 1859 when they emigrated to America [5, 6].

Fifty years after this map was made the Ordnance Survey recorded that a portion of Mackie’s Nursery at Lakenham had become the Townclose Nurseries. Later still, this was to be purchased by the Daniels brothers.

Daniels was sold to Notcutts in 1976. By superimposing modern roads on the nineteenth century map we can see how construction of the Daniels Road portion of the ring road in the 1930s (circled in red) bisected the Townclose Nurseries, with the ‘Notcutts’ portion on the south-western/left side.

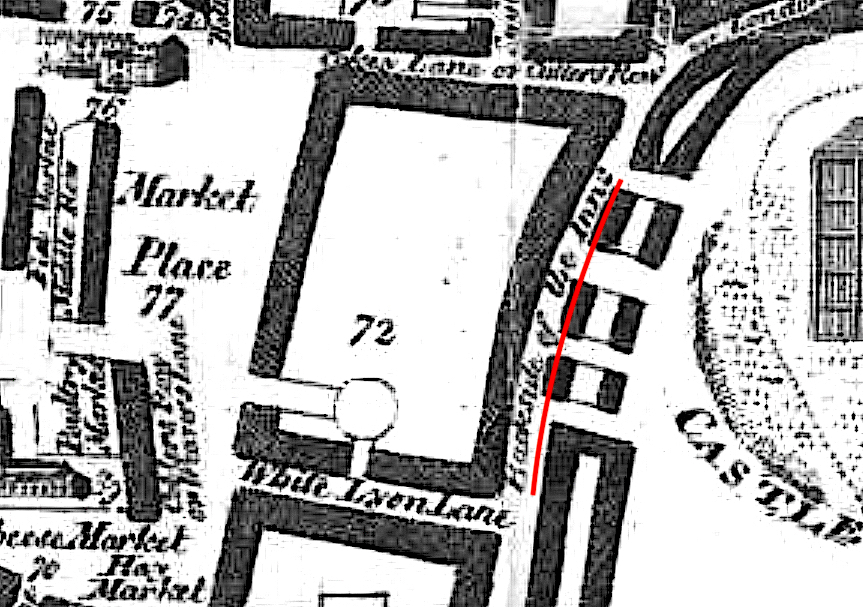

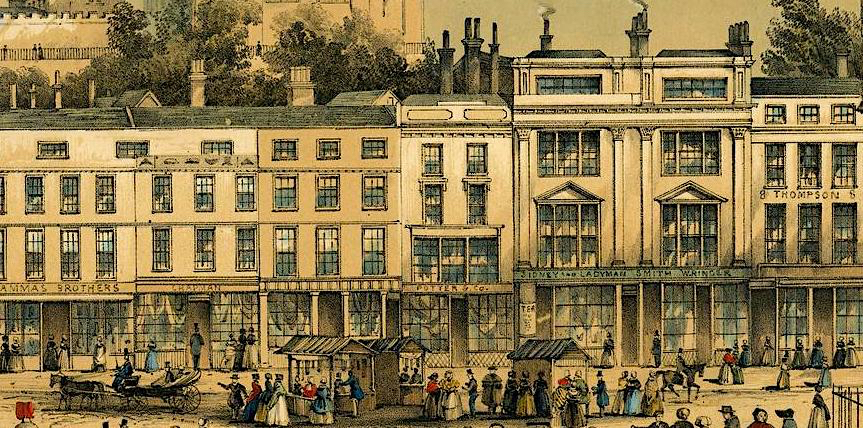

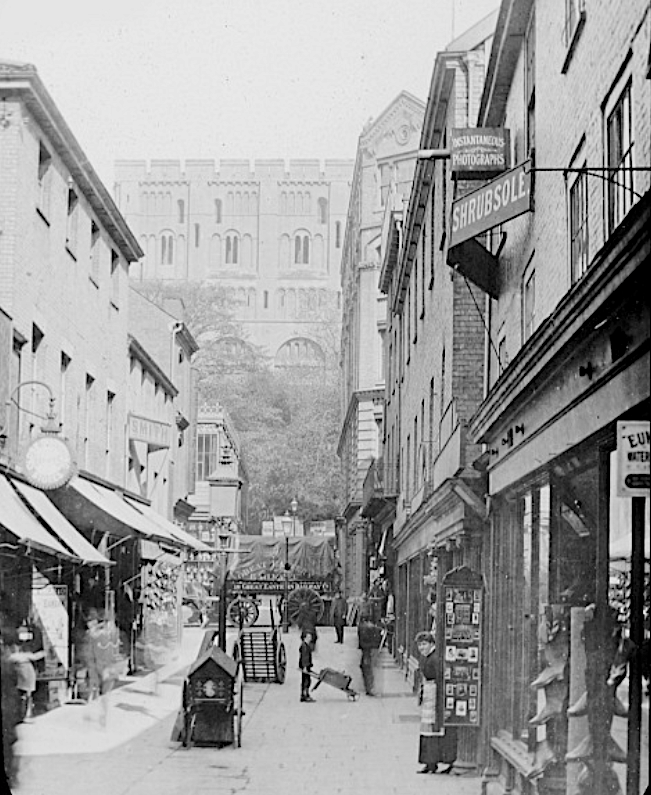

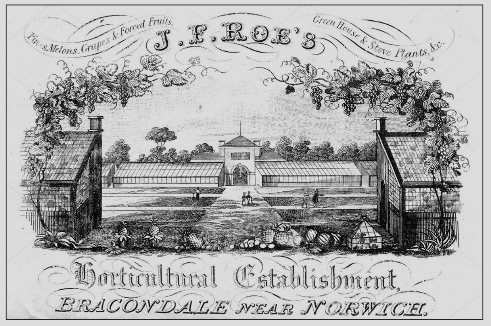

In 1849 Mackie’s ventured beyond the parish of Eaton when they bought The Bracondale Horticultural Establishment, situated in the crook between City Road and Bracondale. Patrons were welcome to visit the nurseries but orders could be placed at Mackie’s warehouses in Exchange Street where customers could also buy seeds and catalogues.

A print in JJ Colman’s album shows Read’s Bracondale windmill (1825-1900). Photographed from the Bracondale Horticultural Establishment it shows a plot with supporting canes and, in the background, heated glasshouses.

The trade card, below, from around 1830, shows the extent of the glasshouses that Mackie inherited when he bought the Bracondale Horticultural Establishment from JF Roe. Their exotic produce appears in the foreground: grapes, melons, ‘forced fruits’ and – most romantically foreign – the pineapple.

As a young boy, before I knew words like ‘epicurean’, I visited Cardiff Castle and was shown a table with a hole through which a pot-grown vine would be placed for the Marquess of Bute’s family to snip their own grapes. Unless, of course, they are peeled for you, grapes are pretty low down on the totem pole of self-indulgence since they can be readily grown outdoors or in an unheated glasshouse. But in previous times the seriously rich would grow pineapples in hothouses, as much a show of wealth as a token of their hospitality. Indeed, from the sixteenth century onwards there was something of a pineapple mania. Large country estates with heated glasshouses and staff could afford to grow their own tender fruit and plants. Norfolk estates may have produced pineapples, but this would have been beyond the dreams of the villa-owning classes in the Norwich suburbs [5] who looked instead to commercial nurseries like Mackie’s to provide their hothouse products.

On a national basis, however, Mackie’s reputation rested not with fancy fruit and bedding plants but with the quantity of their arboricultural stock. In 1849 they auctioned ‘one million forest trees’ and in 1796 they were able to send 60,000 trees to an estate in West Wales. The journey from Norwich to Pembrokeshire required the trees to be carted to London then onwards by sea: such transportational hurdles would be largely overcome by the arrival of the railways. When trains came to Norwich in the 1840s, Mackie’s were able to offer ‘instant arboretums’ of 650 varieties of trees and shrubs for £35 [5].

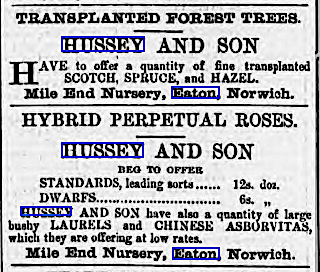

In his History of the Parish of Eaton (1917) [3], Walter Rye mentions ‘the old-established nursery of Hussey in the Mile End Road.’ An advertisement from 1869 shows that their Mile End Nursery was, like its larger competitor (Mackie’s) on the other side of the Newmarket Road, offering trees and roses.

In 1885, Husseys occupied much of the area between Unthank(s) Road and Newmarket Road, stretching from the Mile End Road (now ring road) to what would become Leopold Road.

By the time of the 1908 Ordnance Survey (though for clarity I show the 1919 map), Hussey’s had another nursery on its doorstep. What had been open ground to the west/left of Upton Road was now occupied by large structures, longer and wider than the terraced roads that had arisen on Hussey’s land.

In the period between the 1885 and the 1908 Ordnance Surveys, EO Adcock had bought the open land to the west of Upton Road and established a nursery producing plants on an enormous scale. Meanwhile, Hussey’s had contracted, a good part having been sold to build Waldeck, Melrose and Leopold Roads. The remainder was still accessible through the entrance off Mile End Road [7].

Edward O. Adcock started as an amateur cucumber grower with eight glasshouses at a time when a dozen cucumbers commanded £1 [7]. To put this in perspective, in 1900 the pound was worth over a hundred times what it is today (although cucumbers are still 95% water).

In an article eulogising Adcock as one of the ‘Men Who Have Made Norwich’ [7], he is said to have had 125 glasshouses, each 120 feet long, totalling a quarter of a million square feet of glass. As well as cucumbers, Adcock grew chrysanthemums and, by selling 300,000 per annum, he was claimed to be the largest grower in the world.

Twenty two acres were devoted to asparagus. Adcock also grew tomatoes in prodigious quantities: in one day his staff picked and packed over two tons of tomatoes to be dispatched by rail [7].

What fascinates is the sheer scale at which fruit, vegetables and flowers were produced in just one small part of Norwich. Adcock’s were operating well into the steam age and were evidently able to supply their produce around the country in reasonable time. On a less industrial scale, maps of nineteenth century Norwich give tantalising hints of allotments and other small nurseries such as: Cork’s nursery ground; Allen’s Nursery around Sigismund and Trafford roads in Lakenham; the nursery ground off Dereham Road; the Victoria Nursery in Peafields, Lakenham; George Lindley’s nursery at Catton. Long before refrigerated transport and the concept of food miles it was this web of horticultural enterprises that, together with our farms and markets, fed Norwich.

If you liked this article you may like the Norfolk Gardens Trust Magazine. Membership of the NGT is only £10 per annum, £15 joint, and for this you will receive two copies of the magazine annually, invitations to visit gardens not always open to the public, and talks by leading figures on gardens and the history of designed landscape. Click the link to see more: https://www.norfolkgt.org.uk/membership/

©Reggie Unthank 2021

Sources

- https://familypedia.wikia.org/wiki/William_Creasey_Ewing_(1787-1862)

- https://familypedia.wikia.org/wiki/John_William_Ewing_(1815-1868)?fbclid=IwAR0nbF2FtFgtEnV6xWSr66pwNxH0IxCt3TjeGZ09a16Apjz8B4DvjQ24DHo

- Walter Rye (1917). History of the Parish of Eaton in the City of Norwich . Online at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b756725&view=1up&seq=7&q1=fruit

- ‘Citizens of No Mean City’ (1910). Pub: Jarrolds, Norwich.

- Louise Crawley (2020a). The Growth of Provincial Nurseries: the Norwich Nurserymen c.1750–1860. Garden History v48 pp 119-134.

- Louise Crawley (2020b). The Norwich Nurserymen . In, The Norfolk Gardens Trust Magazine No 29. This article appears in the magazine, available online at: https://www.norfolkgt.org.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/NGT-magazine-Spring-2020.pdf

- Edward and Wilfred E Burgess (1904). Men Who Have Made Norwich’. Reprinted in 2014 by The Norfolk Industrial Archaeology Society in 2014. A truly fascinating read – visit http://www.norfolkia.org.uk/publications.html

Thanks My main source for information on Mackie’s was Louise Crawley, postgraduate researcher at UEA, and I am grateful for her generosity in sharing her researches into ‘The Norwich Nurserymen’. Local historian Vivien Humber kindly shared information on nurseries in the parish of Eaton. I am also grateful to Pamela Clark, Susan Brown, Sally Bate, Tom Williamson and Beverley Woolner. Thanks to the Norfolk Industrial Archaeology Society for allowing me to reproduce the Adcocks photographs, to Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk, and to the George Plunkett archive.