When writing about secular buildings in Norfolk and Norwich I have been struck by the scarcity of the Gothic Revival style. Seeking enlightenment in Wilson and Pevsner’s entry for this county in The Buildings of England I read: ‘The Victorian Age has not left its mark on Norfolk in the way it has elsewhere’ [1]. What happened?

Norwich Cathedral retains much of its Norman structure and illustrates how, in the Norman/Romanesque period (c1050-1150), the weight of the roof was supported on massive stone pillars linked by semicircular arches.

What is Gothic? From the middle of the twelfth century to the sixteenth century, European church architecture was dominated by the Gothic style that strove for greater height and the letting in of light. The preceding Norman period of cathedral building (c1050-1150) was characterised by rounded arches, thick walls and elephantine columns required to bear the enormous loads. In Gothic architecture, by contrast, the stone ceiling was supported by a different framework comprised of pointed arches (ribs) borne on slim columns while the tendency of the walls to bulge outwards was countered by external flying buttresses and their supporting piers. Thinner walls were penetrated by narrow lancet windows that, over the Gothic period (C12-C16), would become flatter and the openings wider, culminating in the huge expanses of stained glass seen in the Perpendicular/Tudor period. But it was the narrow lancet of that Early English period (ca. 1180-1280) that became the most recognisable feature of the Gothic style and, later, a symbol of the Gothic Revival [2].

The evolution of the Gothic style was brought to an abrupt halt by the Protestant Reformation (1534-1603), which stifled ecclesiastical building in England for around 300 years. One major exception was St Paul’s Cathedral (1675-1710) re-built after the Great Fire of London, not in the Gothic style of Old St Paul’s but in a muted Baroque version of Classical architecture with a dome resembling St Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

The renaissance of Greco-Roman architecture – with its temple-like columns, triangular pediments and plain exteriors – was based on principles of symmetry and proportion that were out of step with the pinnacles, pointed arches and asymmetry of the pre-Reformation period. The old way of building was now contemptuously labelled ‘Gothic’ after the barbarian Goths who sacked Rome. This clash was to grumble on until it came to a head in the mid-nineteenth century as the Battle of the Styles [3].

Houghton Hall in north Norfolk is an important example of the Classical Revival, designed in 1722 for the first prime minister of the country, Sir Robert Walpole [4, 5].

We last encountered Walpole’s youngest son, Horace, as an honorary out-of-town member of the Norwich United Friars – a charitable fraternity that held mock ceremonies wearing monkish robes and pink woollen ‘tonsures’ on their heads [6]. Horace did not share his father’s liking for the geometrical rigour of the Classical Revival; instead he built his country seat – Strawberry Hill House, Twickenham (1749-1776) – in the Gothic style, a forerunner of the Gothic Revival that would dominate the Victorian age.

Trowse Old Hall, just south of the Norwich ring road, was built in 1721 and given a Gothick facelift some 50 years later. The Georgians did not really do Gothic, theirs was an age of Classical Revival, and the facelift is described [1] as ‘an amalgam of pattern book examples’ and ‘not an accomplished piece’. It does, however, provide a glimpse of the Romantic mood of the eighteenth century.

The revival of Gothic was more completely achieved in the Victorian era by two thinkers who added a moral dimension to contemporary architecture: John Ruskin and Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin. Protestant Ruskin championed the Gothic. In his influential book The Stones of Venice he complained that the stereotypical approach of Classical architecture was morally deficient compared to prickly pointed Gothic that allowed workers greater freedom of expression.

In his book, Contrasts (1836), the Catholic convert Pugin attributed ‘the present decay of taste’ to the ascendancy of Protestantism. He argued for a return to the values of the Middle Ages that he envisaged with ‘pointed architecture … produced by the Catholic faith’ [7].

In 1836, two years after the Palace of Westminster was destroyed by fire, Sir Charles Barry, assisted by Pugin, won the competition to design new buildings. Barry himself was Classically-minded but the brief was for the Gothic style and it was Pugin’s contribution that helped win, creating an important example for the use of Gothic for Victorian public buildings.

Second place in the competition went to John Chessell Buckler [8] who, in 1825, had designed Costessey Hall for Sir George William Jerningham, a few miles north-west of Norwich. It was constructed of red bricks from George Gunton’s Brickworks on the Costessey estate (see [9] for a fuller story). This ‘Tudor’ version of the Gothic Revival achieves its effect with stepped gables, angle turrets and ‘fancy’ chimneys – but no pointed windows. Intended to be the richest Gothic building in the country Costessey Hall was never completed and was demolished in the twentieth century.

An echo of the hall persists in the contemporary Costessey Lodge (formerly Easton Lodge) built as the lodge to the park [9]. Probably also designed by the architect of the Hall, JC Buckler, this is the perfect example of red Guntons’ brickwork and their magnificent chimneys that can still be seen in Victorian projects around the city [10].

Buckler also advised the one-time County Surveyor, John Brown, on the design of Abbeyfield at the east end of the Anglican Cathedral. Originally the canon’s office (first occupant Canon Heaviside) it was converted to apartments in the 1970s. Pevsner and Wilson [1] thought the building a faux pas, spoiling the east view of the Cathedral. On the other hand Sir John Betjeman thought it was the best house in Norwich (and is a favourite of mine).

Many of the city’s major buildings of the late Victorian era were designed by our two luminaries: George Skipper and Edward Boardman, but neither was an enthusiastic Goth. Skipper’s mercurial talent expressed itself in a variety of styles: Queen Anne Revival, Flemish, French Renaissance and Neo-Classicism [11]. Boardman’s industrial buildings – with round or flattened window arches – are boldly plain for the time but his London Street Improvement Scheme of 1876 is more Gothic in spirit. The building at the corner of London Street and the Marketplace did employ the pointed arch. In the twentieth century its upper storey was removed and its polychrome Cosseyware bricks slathered in cream paint [12]. It survives as a Costa Coffee shop.

In 1700, Norwich was the largest English city after London but by 1801 it had been overtaken by Bristol and seven northern towns. This period marked the slow decline of Norwich’s textile trade. Manchester (‘Cottonopolis’), by contrast, was on the way up [14] and in 1877 celebrated its ascendancy with a Neo-Gothic town hall. Based on the Early English phase of the Gothic period, Alfred Waterhouse’s design was criticised for not being Gothic enough [15], perhaps because it stopped short of the profuse stone carving that typified the later phase of Decorated Gothic.

Norwich had its own medieval – and genuinely Gothic – Guildhall supported by various buildings around the marketplace. The new city hall was built on the eve of the Second World War (1937-8) but by this time the Victorian period had become deeply unfashionable and instead of exuberant Gothic Revival Norwich got austere Swedish Neoclassical [1].

Norwich is not without its Victorian Gothic but you have to search for it. In the absence of flagship projects, like the city hall, public buildings designed by the City Surveyor/Architect tended to be modest affairs. In 1856, when the council banned burials in the overcrowded city churchyards, the City Surveyor, Edward Everett Benest, laid out a new cemetery in the suburb of Earlham [17]. He designed twin chapels in Gothic Revival, one for Dissenters and one for the Established Church. They were incorporated into the crematorium building of 1963-4.

Benest also designed the cemetery lodges.

Benest produced a plain, barely Gothic chapel for the Jewish community.

By contrast, Mr Pearce’s Roman Catholic chapel (1874) is a more enthusiastic version of Victorian Gothic Revival [17].

Across the city at the Rosary Road Cemetery – the country’s first non-denominational burial ground – Benest’s son James designed the lodge in Tudor Gothic. Edward Boardman designed The Rosary’s mortuary chapel in 1879 and would himself be buried here in 1910 [1].

For his design, Boardman drew upon the pinnacles and points of Victorian Gothick, a world away from the Classical Italianate design he had employed in 1869 for his own place of worship, the Congregational Chapel (now United Reformed Church) in Princes Street, Norwich.

Most of the Benests’ civic buildings listed by Pevsner and Wilson [1] were Gothic Revival; for example, the Drill Hall (1866) designed by James Benest for the corner of Chapelfield Gardens. Its Victorian tower made use of an original tower from the old city wall. When the Drill Hall was demolished in 1963 in order to build the Chapelfield roundabout a semi-circle of pebbles was left to mark the tower’s former location [see 18].

Benest junior also designed the old Commercial School (1861) in St George’s Street, now part of Norwich University of the Arts. Its polychrome brickwork and pointed arches provide a rare reminder of Victorian Gothic in the city centre.

In contrast to the scarcity of civic buildings in Gothic Revival the picture is somewhat different for ecclesiastical buildings. Between 1811 and 1871 the population of Norwich more than doubled, with a consequent rise in the number of Anglican churches and Nonconformist chapels [14]. From 1818, a succession of Church Building Acts allowed the Church Commissioners to raise new churches in the growing towns and cities [19]. Christ Church New Catton in the Norwich suburbs is a fine example of a ‘Commissioners’ church’ – recognisably CoE and in the Gothic manner. The County Surveyor, John Brown, designed the New Catton church in the Early English variation.

From 1839 to 1868 the Cambridge Camden Society (rebadged as the Ecclesiological Society from 1845) promoted a return to the church building of the Middle Ages, not for moral reasons but on architectural grounds. By 1844 the Ecclesiologists had settled on Decorated Gothic as their ideal [20].

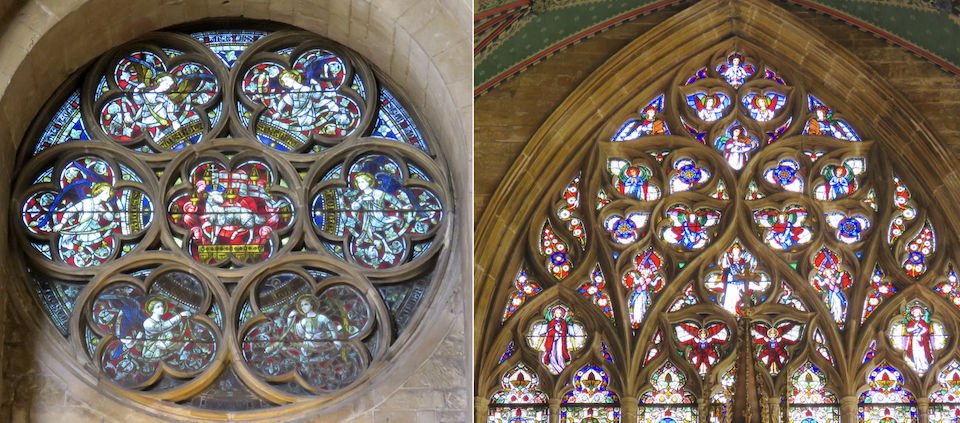

Decorated Gothic The century-long Decorated period, which followed Early English, is associated with the tracery of stone ribs that formed a lacework in the window heads. In the first Decorated phase (Geometric, 1250-1290) designs like trefoils, quatrefoils etc were based on combinations of circles scribed with a continuous rotation of the compass. The second phase (Curvilinear, 1290-1350) is characterised by the ogee, which is produced by joining convex and concave curves to form flowing S-shapes.

On the Nonconformist wing, early chapels tended to be relatively plain and Classical, as in Boardman’s Congregational Chapel above. The move to NeoGothic in the latter half of the nineteenth century can be largely attributed to the Wesleyan Methodist minister and architect FJ Jobson. In his influential book of 1850 he reasoned that Dissenting chapels should not look like Classical warehouses based on the paganism of Greece and Rome but on the architecture amongst which English Christianity had grown – the Gothic style [21].

Jobson also promoted Gothic chapels on the grounds of economy. Unhindered by the high-minded principles of the Camden Group, Dissenting Gothic [22] buildings could be constructed largely in brick (and we know of the difficulties of finding good building stone in Norfolk). Local architect AF Scott, himself a Wesleyan Methodist, designed numerous NeoGothic chapels around the county, usually in red brick with Gothick details showcased on the short gable end (see post on AF Scott [23]).

Designed in memory of his father this chapel is perhaps Scott’s most sumptuous but here, as in many of his projects, most of the ‘carving’ was not chiselled by a stonemason’s hand but made of moulded brick Cosseyware.

Probably the last hurrah for the Gothic Revival in Norwich was the Roman Catholic Church of St John the Baptist (a cathedral from 1976); this was built on the site of the old City Gaol for the fifteenth Duke of Norfolk between 1884 and 1910. The misfortune of the Howards was to have been on the wrong side of the Catholic/Protestant divide and after their land and titles had been forfeit on several occasions they decamped to Arundel in Sussex (for a fuller account see [24]). The Catholic church was designed by the mentally unstable George Gilbert Scott Jr, partly from the ‘madhouse’ (his word), and completed by his brother John Oldrid Scott. The Howards’ waterlogged palace on the riverside had been abandoned some two centuries earlier but for his new project the fifteenth Duke bought a site on a ridge overlooking Norwich. From these commanding heights the church overtopped the Anglican Cathedral, providing a powerful symbol for Catholicism in Norfolk.

The Duke himself insisted on a church in the Early English style and thought it one of the most ‘beautiful examples of pure Gothic to be found in England’ [25].

Sources

- Bill Wilson and Nikolaus Pevsner (1977). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and the North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- Malcolm Hislop (2012). How to Build a Cathedral. Pub: Bloomsbury.

- https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/pdf/10.3366/brs.2010.0202

- Bill Wilson and Nikolaus Pevsner (1977). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 2: North-West and South. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Houghton_Hall

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2023/04/25/the-united-friars-charity-and-enquiry-in-the-age-of-reason/

- AWN Pugin (1836). Contrasts or a Parallel between the Architecture of the 15th and the 19th Centuries. Available online: https://archive.org/details/contrastsorparal00pugi/page/n7/mode/2up?ref=ol&view=theater

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Chessell_Buckler

- https://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?MNF12599-Costessey-Lodge

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/05/05/fancy-bricks/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/02/15/the-flamboyant-mr-skipper/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2023/01/31/plans-for-a-fine-city/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manchester_Town_Hall

- Penelope J. Corfield (2004). From Second City to Regional Capital. In, Norwich since 1550. Eds, Carol Rawcliffe and Richard Wilson. Pub: Hambledon and London.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manchester_Town_Hall

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stockholm_City_Hall

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1001560?section=official-list-entry

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/tag/chapelfield-gardens/

- https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/overview/publicbuildings/#:~:text=The%20New%20Churches%20Act%20of,new%20ones%20had%20been%20constructed.

- https://victorianweb.org/religion/eccles.html

- F.J. Jobson (1850). Chapel and School Architecture. Pub: Hamilton, Adams and Co. Available online: https://archive.org/details/fjjobson1850/page/n111/mode/2up

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dissenting_Gothic

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2021/05/15/af-scott-architectconservative-or-pioneer/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/12/15/the-absent-dukes-of-norfolk/

- Anthony Rossi (1998). Norwich Roman Catholic Cathedral: A Building History. In, Miscellany 1. Pub: The Chapels Society.

Thanks

I am grateful to Peter Bentley Wilson for background on Earlham Cemetery. Thanks, too, to Martin Shaw and Alan Theobald for sharing ideas.

Fabulous work, Reggie.

As young children in the early 1960s, my brother and I would stay overnight at the cemetery’s North Lodge with a lovely couple (Mr. & Mrs. Riches) who used to babysit us whilst our parents were partying. Even as a toddler, I remember it having a spooky, cold, foreboding air. Living in the house was a benefit provided to Mr. Riches as part of his job at the cemetery.

LikeLike

Hello John, Lovely memories of North Lodge. We know it from when it’s open for the National Gardens Scheme. The owners have done a fabulous job in restoring and extending the Victorian building and their garden’s a joy. All best, Reggie

LikeLike

Fascinating article as always! Thank you!

Please don’t forget my request for an equally

illuminating one please, on The Tabernacle,

in Bishopgate. Would be especially appreciated

to see pictures of the interior and details of the

Organ it once contained.

LikeLike

Thank you Richard. Is there enough material, especially old photographs, on The Tabernacle?

LikeLike

I grew up within sight of Costessey Hall, across the Wensum Valley from our back garden. Later, I lived for nearly forty years within sight of Stafford Castle. Both were Jerningham follies, neither was ever completed and both were ruins. Buckler’s Central Tower to the Hall survived for a few years after my time in Taverham until it was struck by lightning in the ’70s. Your photo, which is a rear view of the House, affords a tantalising glimpse of the Chapel, which is possibly the most truly Gothick building to your post and of national importance. It was built in 1809, a year before Pugin was born and designed by Edward Jerningham, a junior scion of the family who was actually Anglican. Very much after the manner of an Oxford College it was ninety feet long and forty five feet high with a Perpendicular West window, Y-traceried fenestration at the sides and an apsidal East end. Ticks all the boxes for a “Gothick” building if you are using Twickenham or Fonthill as a yardstick. Genuine Gothic were the stained glass windows, part of the same job lot from Herkenrode Abbey in the Netherlands that Brooke Boothby donated to Lichfield and can still be seen in the Lady Chapel there. When the estate at Costessey was broken up the glass fetched £17K, a fabulous sum for between the Wars. I think that the Chapel had already been demolished. The Jerninghams were all reburied at St. Walstan’s in the ’50s But where is the glass? Theories abound. A collection in New York or Compton Verney have been suggested. One photo exists of the interior and a drawing made by Buckler, who was impressed by, for its time, a serious attempt at Gothic Revival. I seem to recall it showing a vaulted interior- plaster of course- but can’t locate the book it was in. Buckler almost certainly designed the Lodge at nearby Morton Hall. It’s on the Attlebridge bypass near where the old road rejoins.

PS The East window at Boston that you show has terrific Flowing tracery and is entirely Victorian. It was Perpendicular like all its neighbouring windows until Scott “improved” it. Pevsner says it’s a copy of the, much larger, East window at Carlisle. It isn’t, it’s close to, but not quite, Selby, so Scott at least gets a Brownie point for originality! MGR.

LikeLike

Thank you for the fascinating comment, Michael. I have often wondered about Morton Hall lodge and had even thought of including it in the post. It is not dissimilar to Easton/Costessey lodge but the Heritage Norfolk site, which dates it to 1830 or 1860, states it is “similar to the schools at Attlebridge, Wroxham and Ringland built by a Mr Keaton”.

LikeLike

Another splendid post. My parents married in Christ Church New Catton and my mother’s elder brother’s name is on the War Memorial there. Between them the Boardman family and Scott seem to have designed most of the dissenting chapels in Norfolk and worked for most if not all of the various sects in spite of their own positive affiliations!

Don Watson

LikeLike

I envy you Don, with your long associations with Norwich.

LikeLike

Love this. Thank you. Great research for a short story I’m writing. Hope all is well with you! Still dip into your books and I see you have another one out!

Best wishes

Daniel

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Daniel, All is good. Are you writing a story about Georgian Norwich? Look forward to that (and let me know if I can help in any way).

All best, Reggie

LikeLike