Tags

Arts and Crafts Movement, bricks, Cosseyware, Edward Boardman, George Skipper, Gothic revival, Norwich buildings

The look of a place

Until the coming of the railways in the mid C19th, towns were necessarily made from the materials around them. The honey-coloured villages of the Cotswolds look so right in their environment for even the stone roof-tiles topping the honey-coloured stone walls derive from the bedrock on which they stand. But as we know, Norwich is about as far from decent building stone as you can get. Only the Church and rich grandees could afford to import building stone by water; famously, the Normans built Norwich cathedral of stone shipped from Normandy. So between the age of the medieval timber-framed building and the arrival of steel-reinforced concrete the majority of the city’s buildings were made from clay in the form of brick and tiles. This post focuses on decorative brickwork, produced by one family, that characterised Victorian building in Norwich.

Norwich roofscape from St Giles car park

Around 1860, Norfolk contained 114 brickyards spread throughout the county so though Norfolk may have lacked stone there was evidently no shortage of brick clay [1]. In the pre-railway age, bricks tended to be made close to the building site due to the difficulty of transporting heavy loads over long distances. The arrival of railways in Norwich in the 1840s allowed building materials, such as Welsh slate, to be transported more easily and this, combined with the repeal of the tax on bricks in 1850 [2], contributed to the explosion of terraced-house building in Norwich [3]. Surrounding Norwich were the brickyards of Banham, Lakenham, Reedham, Rockland St Mary, Surlingham and Welborne [1] but the one that perhaps had the greatest effect on Norwich via its red or white decorative products was the Costessey Brickyard five miles to the west, run by the Gunton family.

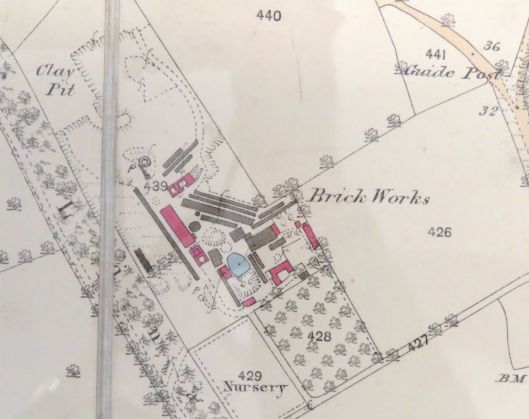

Gunton Brickyard, Costessey Nr Norwich. (c) Ordnance Survey 1882. Image source, Norfolk Heritage Centre

- Many years ago I saw comedian Ken Dodd at the Theatre Royal Norwich. Part of his introductory schtick was to play with local names, pronouncing Happisburgh as Happy’s berg instead of Hay’s bruh and Costessey as three-syllabled Coss-tess-ee instead of Cossey. How we laughed. Anticipating Doddy’s difficulties the Gunton family, who managed the Costessey Brickyard from the 1830s to 1915, called their range of ornamental bricks ‘Cosseyware’. As the map shows, it was quite a large enterprise, employing 40 men and boys in 1882 [4].

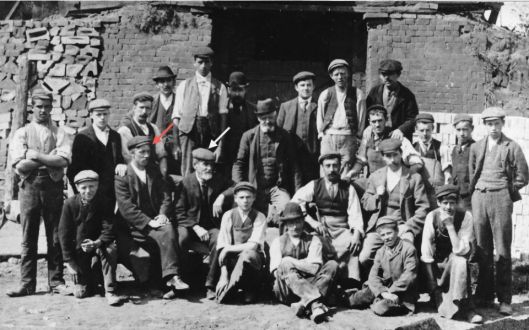

(In an update) Costessey resident Peter Mann wrote in to say he was able to name all the workers at the Costessey brickyard (see footnote at end). Excitingly, he identified James Minns with son John Minns seated on his right. Both were labelled as “Carvers of Norwich”, consistent with census returns giving their occupations as ‘carver’ (or, once for James, ‘sculptor’). The entry for Minns on the Mapping of Sculpture website gives his full name as James Benjamin Shingles Minns (ca 1828-1904). James was sufficiently confident of his skill to submit (successfully) a carved wooden panel of ‘A Happy Family’ to the 1897 Summer Exhibition of the Royal Academy; he had also carved the mantelpiece and panelling for Thomas Jeckyll’s commission for the Old Library at Carrow Abbey (1860-1). The presence of this highly skilled sculptor and his son at the Costessey Brickyard strongly suggests they were responsible for the ornate ‘fancy’ bricks and panels for which Guntons were locally renowned. From his independent status as ‘Carver’ it seems possible that “James Minns of Heigham” might have been freelance rather than a full-time employee, especially since his address was ca. five miles away from the Costessey Brickyard. [For more on Minns see the ‘Angels in Tights’ post].

Employees of the Guntons Brickyard Costessey. James Minns is arrowed (white) with his son John, arrowed red. Pre-1904. (c) Ernest Gage Collection at Costessey Town Council. The key to the workers can be seen in the footnote at the end.

Other yards made decorative bricks in Norfolk during the Victorian heyday but Costessey Brickyard became pre-eminent through its association with Costessey Hall. In 1824, when Sir George William Jerningham became the 7th Baronet Stafford, his “commanding and forceful”[4] wife became dissatisfied with the old Tudor hall at Costessey and so began an overambitious plan to build an elaborate, battlemented, pseudo-Tudor replacement. Designed by John Chessel Buckler, Costessey Hall was to be “the richest Gothic building in England” [quoted in 6] but it became a folly that was never fully completed [4]. The fortunes of the Guntons coincided with the rise and fall of the Hall.

Costessey Hall 1870, architect John Chessell Buckler. Source: RIBA Collections

Costessey Hall showing Tudor Revival chimneys made at the Gunton Brickyard. Source: Picture Norfolk and Museum of Norwich at the Bridewell

Gunton Bros catalogue 1907. Source: Norfolk Heritage Centre

In 1862, the owner of Costessey Hall, Sir Henry Valentine Stafford Jerningham, who had produced no heir, asked the wonderfully-named Masters of Lunacy to declare the next in line (his nephew The Right Hon. Augustus Frederick FitzHerbert Stafford Jerningham) to be of unsound mind [5]. When nephew Augustus inherited the estate in 1884 the Lunacy Commissioners suggested the Hall was not suitable for him and that it be closed up. But Norwich’s foremost architect Edward Boardman argued against closure, marking an early connection between him and Costessey. On Augustus’ death his brother, Sir FitzOsbert Edward Stafford Jerningham, inherited to become the last Baron Stafford to live at the Hall. He was described as an eccentric who, mindful of what had happened to his brother, kept his back to the wall (literally) and refused to leave the confines of the estate [4]. After his death the estate was seen as a white elephant to his inheritors, leading to the long drawn out demolition of the Hall.

Demolition of Costessey Hall began in 1920; seen here in 1934 (c) www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk

Tastes had already begun to change some years before the demolition of the Hall. During the second half of the C19th one of the styles within the all-embracing Arts and Crafts Movement was for decorative “Gothick” brickwork (usually red) of the kind that the Guntons had made first for Costessey Hall then for the wider public. However, this fascination for Tudorbethan brick was in decline by the turn of the C20th and in 1915 the Guntons failed to renew their lease at Costessey. All that remains of the Hall is the Belfry Block off the eighteenth fairway at Costessey Park Golf Club. And all that remains (reportedly) of the Brickyard is a derelict kiln at the end of Brickfield Loke.

The family continued making ordinary bricks (known as ‘builders’) at their Barney, Little Plumstead and Runton works but these outposts closed in 1939 due to fears that the kilns could act as beacons to enemy planes.

Stoking the furnace to burn bricks, probably at Gunton’s yard at Barney. Source: Ernest Gage Collection at Costessey Town Council.

After the main phase of building the Hall, George Gunton began to look for alternative outlets for his decorative bricks; their widespread dispersal was greatly assisted by the 1850 repeal of the brick tax – a tax that had been particularly punitive for oversize decorative bricks [6]. Cosseyware began to increase in popularity, first under George Gunton then from 1868 under his sons William and George. It was therefore during the second half of the C19th that Costessey clay started to have an impact upon the appearance of the city.

At the back of the Old Red Lion Beerhouse at 64 Costessey West End, George Gunton built an outhouse. Local historian Paul Cooper told me: “The Red Lion outbuildings would have been a showroom and where they did the intricate carving on the chimneys and fireplaces.”

Cosseyware letter bricks spell out the name of George Gunton. Bricks like these can be spotted throughout Norwich. Source: ‘Picture Norfolk‘ and Museum of Norwich at the Bridewell.

The same gable end in 2016, minus doorways. Note the Cosseyware chimney.

Cosseyware chimneys in Costessey West End 2016. Left: grapevine pattern; right: ‘patriotic’ rose/shamrock/thistle bricks on the building shown in the previous image.

The GG tiles beneath the grapevine-patterned chimney on the left suggest this is one of the nine houses that George Gunton is known to have built between 1850-1860 [6] in West End, not far from the brickyard.

Letter and number bricks, identical to those at Costessey West End, on the gable end of a house at the junction of Belvoir and Earlham Roads, Norwich

Aucuba Villas (1896) on Earlham Road, Norwich. [Aucuba is an evergreen shrub]. Note the characteristic Gunton ‘A’ in all these examples.

... and again at Park Lane, Norwich

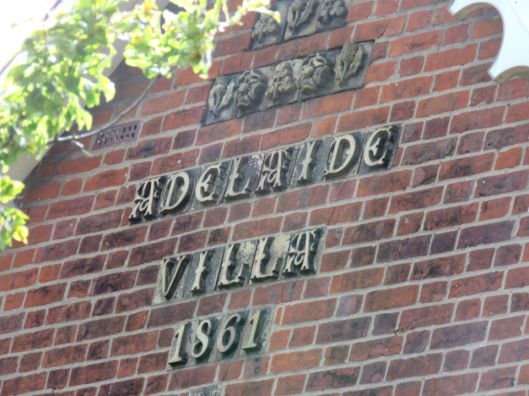

The rose bricks above the ‘Adelaide Villa’ lettering were still to be found in the Gunton Bros 1903 catalogue

The same bricks from the ‘patriotic’ range (but no leek!) were incorporated into many of the walls and features of the Plantation Garden, Norwich.

In the mid 1850s, Henry Trevor created The Plantation Garden near St John’s Cathedral on Earlham Road in an old chalk and flint mine. It is a Victorian delight, benefitting from years of careful restoration. If you want to see a range of Gunton’s products look no further: fragments from more than 15 of their 34 patterns on chimneys can be identified here [7].

The Plantation Garden’s fountain (1857) with its characteristic mixture of flint and ornamental Cosseyware

Not far from the Plantation Garden this plaque can be found on Earlham Road near the junction with Park Lane.

Two of Norwich’s foremost architects, Edward Boardman and George Skipper, used Cosseyware to ornament their buildings – a choice that helped define the appearance of the Victorian city. In 1869, Boardman designed the Princes Street Congregational Chapel (now United Reformed Church) and adjoining Church Rooms in an Italianate style.

Boardman’s Congregational Chapel, with triangular pediment, is seen beyond the Church Rooms that he also designed. The Rooms have been renamed Boardman House and are now part of Norwich University of the Arts.

Gunton’s white decorative wares were used to realise the classical Italian style

Pale brick from Gunton’s was used again by Boardman for his office block, Castle Chambers, in Opie Street off Castle Meadow.

Castle Chambers 1877. Architect Edward Boardman

Some 20 years later Boardman was to design the Royal Hotel around the corner on Agricultural Hall Plain in red brick and ornamental Cosseyware. This hotel replaced the old Royal Hotel that provided the site for Skipper’s Royal Arcade off the marketplace.

Royal Hotel, Norwich (1896-7). Architect Edward Boardman

The Arts and Crafts Movement roamed widely for its pre-industrial architectural influences: the Royal Hotel is described as being “free Flemish” [8]. The lower levels are relatively plain but further up the stylistic tics of neo-Renaissance architecture become more apparent in the ornamented string courses, gables and pinnacles – all richly decorated in Cosseyware.

The diamond shapes in the triangle at the centre of the gable above form a repetitive pattern or diaper that can be seen on several buildings around Norwich

The former carriage entrance of The Green House 42-46 Bethel Street offers a fine example of Gunton’s diapering …

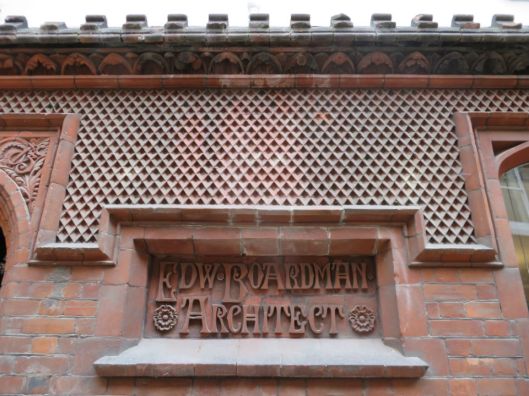

Boardman used red Cosseyware diapering on his own offices in Old Bank of England Court, Queen Street. His nameplate, which is a gem of Victorian lettering, was custom made rather then being made from Gunton’s individual letter bricks.

Gunton’s red clay was used to make these intricate tableaux on what were once George Skipper’s offices, now subsumed into Jarrold’s department store on London Street.

Arts and Crafts: Skipper is showing clients the Art of architecture while workmen demonstrate the various Crafts of building

In this other Cosseyware panel, Skipper introduces his work to potential clients. In the background are three of his completed Norwich buildings [9]. Now that we know what James Minns, the carver, looked like it is highly likely that top-hatted Skipper is pointing to a shield held by Minns who worked on several joint projects.

Glance right next time you exit Norwich Rail Station and you will see one of the most richly decorated buildings in Norwich – 22 Thorpe Road . It was designed ca. 1900 by A F Scott and Son [6] using red Cosseyware in Franco-Flemish neo-Renaissance style.

Bewick House, 22 Thorpe Road, headquarters of the Norfolk Wildlife Trust

The moulding is still crisp after more than 100 years

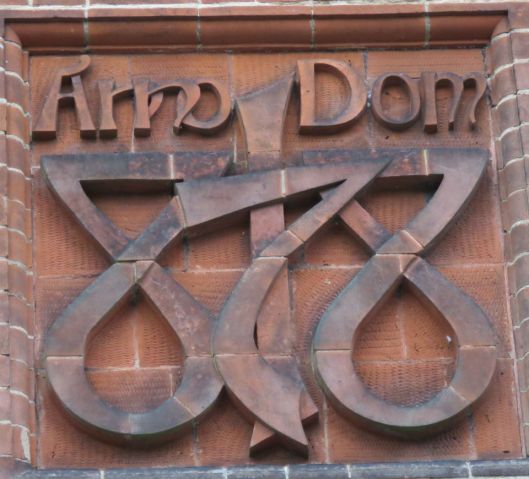

Buildings in the last quarter of the C19th buildings were often exuberantly marked with terracotta date plaques – perhaps an expression of the confidence felt by Victorian architects and their clients at the height of Empire. This example below is over one metre tall:

1878. Number 13 Ipswich Road

1875. Edward Boardman’s office in Old Bank of England Court

1877. Boardman’s Castle Chambers, Opie Street, Norwich

1894. Number 22 Thorpe Road

1886. Norwich Gaol, Mousehold Heath

1888. St Ethelbert’s House, Tombland, Norwich

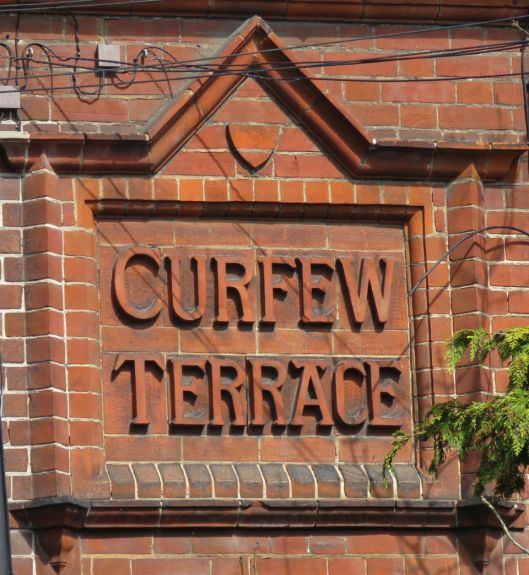

From terraced houses to large public buildings, Cosseyware left its distinctive mark on Victorian Norwich.

©2016 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- Lucas, Robin (1993). Brickmaking. In, An Historical Atlas of Norfolk. pp154-155.

- Lucas, Robin (1997). The tax on bricks and tiles, 1784-1850: its application to the country at large and, in particular,to the county of Norfolk. Construction History vol 13, pp29-55.

- O’Donoghue, Rosemary (2014). Norwich, an expanding city 1801-1900. Larks Press, Dereham.

- Gage, Ernest G. (1991). Costessey Hall. A retrospect of the Jernegans, Jerninghams and Stafford Jerninghams of Costessey Hall, Norfolk. Available from: http://www.costesseybooks.co.uk/purchasebooks.htm

- Gage, Ernest, G. (2013). Costessey: A Look into the Past. Pub: Brian Gage, 31 Eastern Ave, Norwich NR7 OUQ (also, see preceding link).

- Lucas, Robin (1997). Neo-Gothic, Neo-Tudor, Neo-Renaissance: The Costessey Brickyard. The Victorian Society Journal pp 25-37.

- Adam, Sheila (2009). The Plantation Garden Norwich: A History and Guide. (Available from the Plantation Garden, 4 Earlham Road, Norwich).

- Pevsner, Nikolaus and Wilson, Bill (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Yale University Press.

- Bussey, David and Martin, Eleanor (2012). The Architects of Norwich. George Skipper, 1856-1948. The Norwich Society.

Visit: the excellent website with many photographs of Costessey Hall and of brick-making on: http://www.costesseybooks.co.uk/contact.htm. I am grateful to Brian Gage for generously providing information and access to the Ernest Gage Collection. Thanks are also due to Paul Cooper, local historian, for sharing his extensive knowledge of Costessey Hall and the Gunton Brickyard. I am grateful to Peter Mann for naming the Costessey workers.

Visit: www.picture.norfolk.gov.uk. An endlessly fascinating archive of photographs of old Norfolk with a great series of photographs of old Costessey Hall. Thanks to Clare Everitt, who runs the website, for her help.

Visit: if you haven’t already seen the Plantation Garden you are in for a treat. Open daily 9.00am – dusk. Their excellent website is well worth exploring (http://plantationgarden.co.uk).

Footnote: Peter Mann mailed in to provide the names of men in the photograph of the Gunton workers. He says: “My Grandfather and Great Grandfather are included in the Picture. Names as follows:

Back Row L/R, Albert White, John Ireson, Charles Doggett, George Gunton (Part Owner), Walter Ireson, James Simmons.

Middle Row L/R, Daniel Drury, William Gunton Jnr, Fred Barber, William Gunton Snr (Part Owner), Noah Mansfield, H.E Gunton, Charles Gotts, Thomas Mann Jnr. Seated Row, Arthur Paul (kneeling), John Minns, James Minns, (Carvers Of Norwich), Joseph Goward, Thomas Mann Snr.

Bottom Row, Robert Burton, James Paul, William Bugdale, Harry Banham.”

WELL RESEARCHED AND NICELY WRITTEN, A FINE RECORD OF GUNTONS BRICKMAKERS ….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Paul. Your own research into the Costessey Brickyards was so helpful to me.

LikeLike

Yet another amazing article on what people can see in Norwich, if only they’d lift their eyes up. Fascinating account of the products of a lost local industry.

Keep up the good work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Much appreciated Jonathan. Your father’s photographic archive of old Norwich, which you maintain, has been an inspiration. http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Website/

LikeLike

Really interesting. Gunton must be a Norfolk name? Is there a connection between the family you write about and the Gunton Arms?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gunton Arms is a North Norfolk favourite. I haven’t been able to find a connection with the Gunton Brickworks though.

LikeLike

When did Barney Brickworks finally close after the war, please

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Tony,

According to the National Archive it was the blackout restrictions of 1939 that caused William Herbert Gunton to close all his brickyards.

LikeLike

Can give you more information on the “Group of Workers at Costessey Brickworks”

as my Grandfather& Great Grandfather, are included in the Picture,

Names as Follows,

Back Row L/R Albert White::: John Ireson::: Charles Doggett::: George Gunton (Part Owner):::Walter Ireson::: James Simmons.

Middle Row L/R Daniel Drury::: William Gunton Jnr::: Fred Barber :::William Gunton Snr (Part Owner)::: Noah Mansfield:::H.E Gunton:::Charles Gotts::: Thomas Mann Jnr;;;

Seated Row Arthur Paul (Kneeling) John Minns:::James Minns::: ( Carvers Of Norwich)::: Joseph Goward::: Thomas Mann Snr:::

Bottom Row Robert Burton::: James Paul::: William Bugdale::: Harry Banham.

I think its nice to put names to the Faces, just wish more people would do it when taking photo,s even today???

Regards Peter Mann (Cossey)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks for this Peter. I have added these names in a footnote to the article. It’s good to put faces to the names of all workers and for me to see who the Guntons were in particular.

LikeLike

Super article on Gunton’s brick products. I saw some great chimneys built with bricks with floral designs on the redundant Mattishall Primary School in 2011. The building was awaiting demolition and has now gone…what happened to the decorative bricks I wonder?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure, Sally, about what happened with the Mattishall bricks. Would be good to know that the bricks from the Old Hospital at Little Plumstead can be salvaged after the recent fire.

LikeLike

The Mattishall school brick chimneys were used as the basis for the war memorial, which now stands alongside new housing on the grounds of the old school. They are in good condition and sit in a quiet corner of small play area. I have recently moved into a property in Mattishall which has four ornate chimney stacks, almost identical to those from the school. Each bears one of the four ‘patriotic’ rose/shamrock/thistle/? designs. It is great to read a little about the background of the company which was responsible for these lovely pieces of history.

LikeLike

Hello James, Friends of mine from Mattishall also have some Guntons ‘patriotic’ bricks from the school and are putting them to good use. If you send me your email address (it won’t be published) I can put you in touch.

LikeLike

hello, I have just stumbled into your web page and found it so interesting, thank you. One of the examples of decorative brickwork is my house!(Earlham terrace on corner of belvoir street and Earlham road). I was really happy to see it on here as I really love it. I’m trying to find out some history on my house, would you have any idea who would have built it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Sarah,

So pleased to make contact with the owner of the gable end with the Guntons’ letter bricks. I don’t know offhand who built your house but if you contact me via the website with your email address (it will not be published!) perhaps we could discuss it. Reggie.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this. I’ve been living in Norwich for many years just vaguely aware of the wonderful brickwork all around lurking about in the eye’s corner. It’s put this vague awareness and appreciation into concrete form. Bit pretentious I know but I’m trying to say that I could feel the craftsmanship was there but not sure what it was. Now I am a bit clearer. thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree entirely, Carolyn. The materials that make up our built environment are so often overlooked but crucial to the feel/look of the place. Bricks are bricks but we are fortunate to have had skilled carvers who made big difference.

LikeLike

Excellent blog!

The brick scenes on the Jarrolds building (Skipper’s old office) are hand carved brick, their square shape is typical. Probably by a sculptor named Minns, who regulalry worked with Skipper, both in brick and timber.

I believe Guntons also took over the brickworks at East Runton for a time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the informative comment Andy. In a later blog (angels-in-tight) I mention the connection that Skipper and Guntons had with Minns. Turns out that two of the seated figures in the photo of the brickyard workers are James Minns with his son. It’s good that we can now put a face to a respected local craftsman. I’d be fascinated to hear any further information you might have about Minns. Kind regards, Reggie

LikeLike

Thank you for your great articles. I am currently working in a series of artworks based on Norwich…some of which are architectural details from iron work and bricks….. I love anything typographic and have been looking into the cast iron lettering still left on Anchor House, (Bullards brewery) it is very similar in style to the letters that adorned Panks in Castle Hill…and the Great Eastern Hotel that was on Foundry Bridge…I’m presuming they were cast by Barnards but how can I find out….I’m an artist obsessed by history..not a historian!

LikeLiked by 1 person

So pleased you made contact Sally – your website looks great. I had noticed the similarity between the Panks lettering and that on the Anchor Quay building but was unaware of the lettering on the Gt Eastern Hotel where the Hotel Nelson once stood. I’d love to see a photo. There is similar-ish typography on the Guntons’ brick plaque for Edward Boardman’s offices. I don’t know whether Barnards cast the letters and I can only suggest that you try the Norfolk Record Office. There were other Norwich foundries. I once spent an interesting hour going through the box of Boulton and Paul catalogues; it’s a long shot but the NRO might have something on Barnards.

LikeLike

Pingback: The flamboyant Mr Skipper | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Post-medieval Norwich churches | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

trying to find out something about my gtgtgrandfather William James Gilbert who was described as a Brickmaker and lived in Costessey. Enjoyed all the pictures and information.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Tracey, I’ll put you in touch with a local historian who is familiar with the names of the Costessey brick makers. Best wishes, Reggie

LikeLike

Pingback: Catherine Maude Nichols | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Going Dutch: The Norwich Strangers | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: James Minns, carver | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: The Plains of Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Building bricks have a long history over the years. I love reading this article. Keep it up. Thank you.

LikeLike

I liked the idea that Victorian artisans could turn up most anywhere that had clay and make bricks. Thank you for the kind comment Barbara

LikeLike

Pingback: Madness | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

You may be familiar with the last surviving fragment of Costessey Hall. The Costessey Lodge, AKA Easton Lodge, is on the old Dereham Road between the Round Well and the Showground. Almost certainly by Buckler- the first thing the Royals would have seen when they visited, so it would have had to have been finished at the time! Still inhabited- I think it’s now an Air B&B- and chock-full of Cosseyware. Barley-sugar chimneys galore. Not far away and even prettier is Morton Lodge, just outside Attlebridge on the Fakenham Road. Feels as though it should be part of the Costessey estate but it’s just too far away. No attribution, but it’s just got to be by Buckler- he probably got the gig on the back of his work next door , rather like Teulon with his work at Shadwell Park. Another burning issue about Costessey is- what happened to the stained glass, part of the tranche from Herkenrode that ended up in the Lady Chapel at Lichfied? In 1809 Edward Jerningham built a Catholic Chapel at the Hall on about the scale of that at an Oxford College. It features on plenty of pre-1915 photos but , apart from a sketch by Buckler there’s only one tantalising shot of the interior and you can’t see the glass, which was probably supplied by JC Hampp, a Norwich merchant who salvaged much German and Flemish work from monastic victims of the Napoleonic Wars. When the estate was broken up pre- WWI the glass exchanged hands for £17K and that’s the last you hear of it. If what is still in Lichfield is anything to go by it ‘s very good and deserves better than being squirrelled away in a bank vault somewhere. We lived in Taverham for my formative years and could see Costessey Park across the valley from our back garden. For forty years I lived in Stafford and likewise had a privileged view of another Jerningham folly- Stafford Castle! MGR.

PS Did you know that the window tracery at St. Edmund’s Parish Church in Costessey, along with several tombs in the churchyard, are made of the buff-coloured Cosseyware. More hard wearing,I’m told.

LikeLike

There is so much to see around ‘Cossey’. The high street is full of reminders of the Guntons. I shall go and have a closer look at Easton Lodge. Not sure if I know Morton Lodge – would Buckler, who had almost won the House of Commons commission, deign to design lodges. Perhaps so. Again, I’ll have a closer look. As for the glass, in the early days of blogging I was invited to see two panels in a terraced house in the city that were said to have come from Costessey Hall, suggesting that the glass may have been redistributed piecemeal.

LikeLike

Hi Mike Revell … There is a very rare book in Costessey Town council archives listing all the stain glass that was in St Augustines chapel (before it was removed) with many full colour and black/white plates. As the Town council archivist if you wish to see the book please let me know .. Paul Cooper

LikeLike

Pingback: Plans for a Fine City | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Gothick Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH