No Georgian new town arose in Norwich and what fresh development there was barely disturbed the medieval footprint [1]. The building campaigns of the late 19th and the early 20th centuries had a much greater impact as they cut through the narrow streets in response to the arrival of the railway, the electric trams and the construction of factories. In 1988, in conjunction with the Victorian Society, the late Rosemary Salt invited a reappraisal of the city’s Victorian and Edwardian architecture in an exhibition entitled ‘Plans for a Fine City’ [2]. I have been retracing her steps at the Norfolk Record Office.

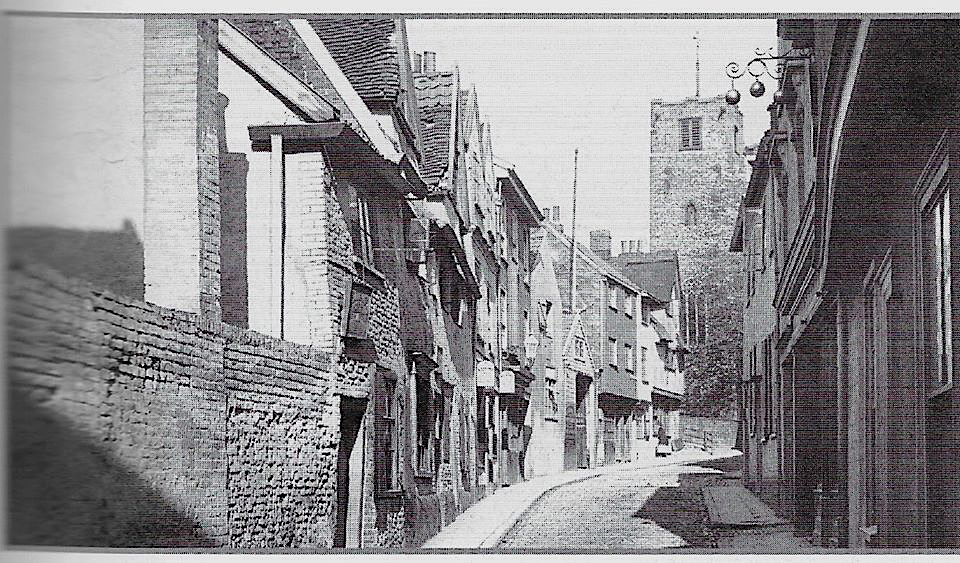

Major changes to the traffic flow (horse-drawn and pedestrian) were forced upon the city by the arrival of the railways in the 1840s. A decade or so later, Prince of Wales Road – constructed on the rubble from the City Walls at Chapelfield – was built expressly to connect Norwich Thorpe Station to the city centre. Before the trains, London Street was a narrow medieval lane but in 1856 was widened to 15 feet (4.5metres) then to 35 feet in 1876. This removed most of the old buildings of which the Bassingham Gateway – now the Magistrate’s Entrance to the Guildhall – is a reminder.

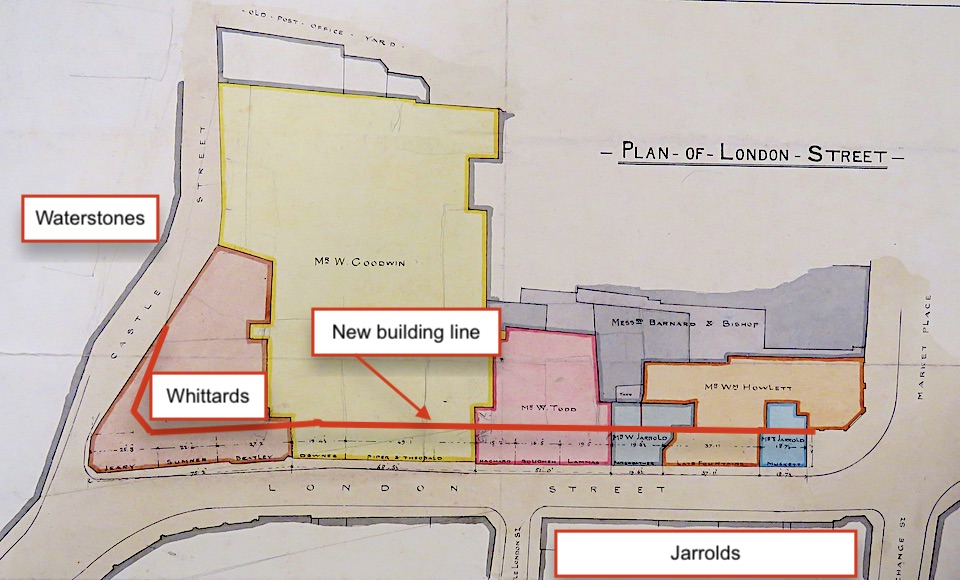

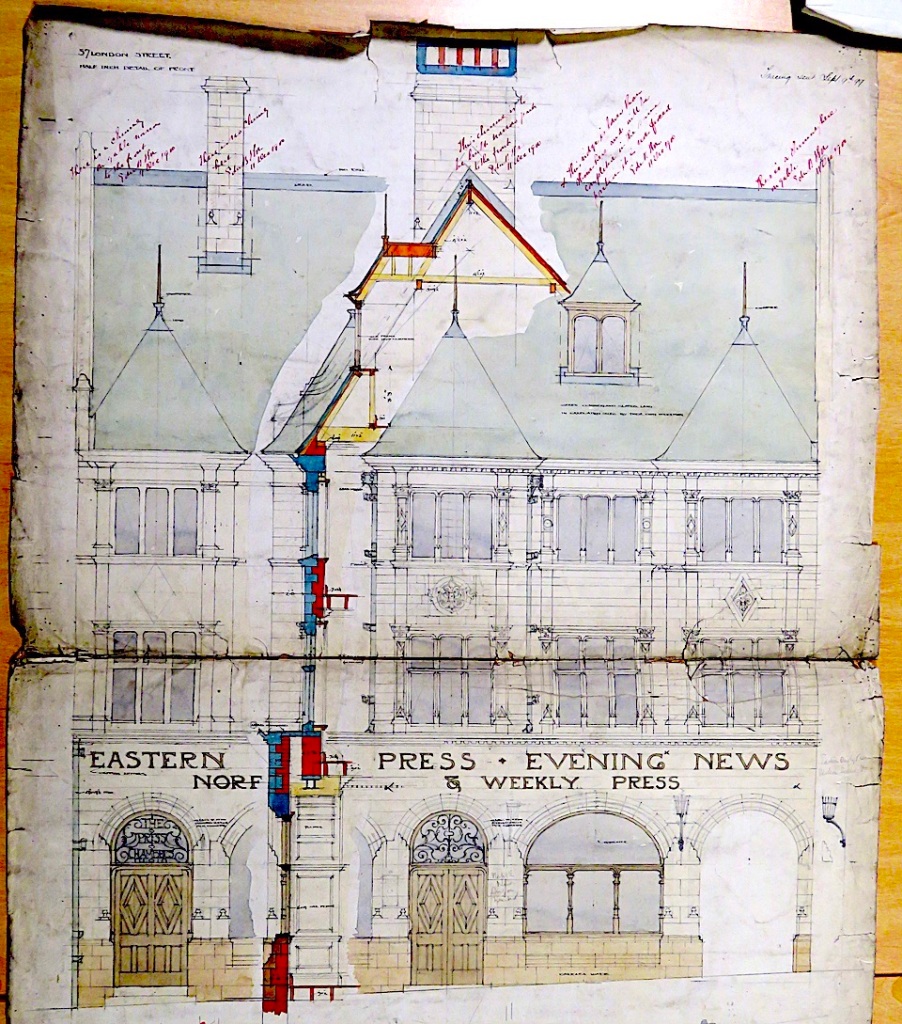

In 1876 the local architect Edward Boardman designed the London Street Improvement Scheme, the initial phases of which cost £27,000. The new London Street was to form a spine of improved access for wheeled traffic between Thorpe Station and the marketplace but the larger vision included associated thoroughfares of Castle Street, Opie Street and Davey Place [2]. The determination to widen the medieval lane was reinforced by compulsory purchase orders as the new building line shows for Castle Street and the southwest end of London Street.

One of the first buildings to be raised (1876) was Howlett & Sons’ piano warehouse at the corner of London Street and the marketplace [2-4].

In Rosemary Salt’s words [2] ‘The building exists in mutilated form’ after the attic storey was removed and the facade – composed of carved red bricks from the local Costessey Brickworks [5] – was obscured by cream paint.

The stuccoed, four-storeyed building to the right of Costa Coffee as it turns around to face Gentleman’s Walk was designed by Edward Boardman in 1872, just before he began planning the improvements to London Street.

The drawing shows a building profusely decorated with ironwork for this was the showroom of Barnard Bishop and Barnards whose Norfolk Ironworks was in Norwich-over-the-Water. They also had a showroom in London. Having written several posts about their designer Thomas Jeckyll I looked closely to see if any of his ironwork remained on what had become Hope Brothers shop. By the time of this photograph of about 1930 the ornate panels on the ground floor had disappeared; the cast-iron balustrades on the second floor balconies, which were designed by Jeckyll, remained but by the time George Plunkett visited in 1938 (not shown) these had disappeared too.

The other corner of the London Street Improvement, at the junction with Castle Street, is currently home to Whittard of Chelsea. Built in 1880, its surface is also decorated with Cosseyware brick diapering – a feature the architect repeated in other projects, including The Royal Hotel (see below). While it differs in detail from the building at the other end – notably in the design of the window heads – both are built of red brick in a free Victorian Gothic style that promised a coherent approach to this block on London Street.

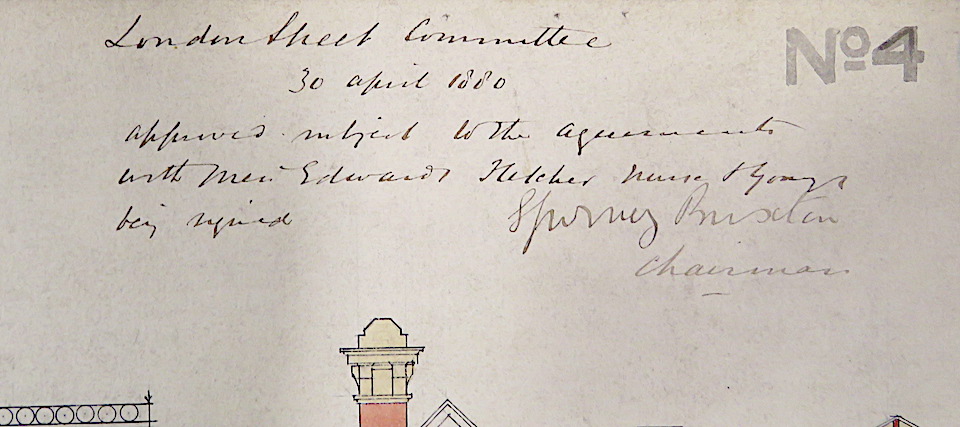

In the top right-hand corner of the plan appears the signature of S(amuel) Gurney Buxton, chairman of the London Street Improvement Committee.

In the eighteenth century, when the Norwich and Norfolk wool industry was at its peak, Quaker families like the Buxtons and the Gurneys became wealthy by forming country banks that supplied credit to other weavers. These families were part of a network forged by business, Quakerism and intermarriage. In 1896, 20 such local private banks merged to form Barclay & Co Ltd, now the second largest bank in the country. Although Gurney & Co were only marginally smaller than Barclays their name is unlikely to have appeared in the corporate title for it was tainted by the failure of Overend Gurney & Co[6,7]. The insolvency of this, the City of London’s oldest bill-brokerage firm, drove investors to withdraw funds from other banks, spreading financial panic in what became known as the Black Friday of May 1866.

How grand a 100 yard-long arcade of Victorian shop windows would have looked in this stretch of the street. But this, it seems, was never part – or allowed to be a part – of Boardman’s vision. The differences in architectural detail between Messrs Howlett and Mr Beatley’s buildings, which bookend the street, are relatively minor and in keeping with another five-bayed red-brick building adjacent to Howlett’s piano store. Any visions of unity appear to have been dashed early on, however, by the insertion of a three-and-a-half storey building with projecting bay windows.

Formerly the Midland Bank, now the HSBC, the building was unsympathetically resurfaced in 1971with ‘boldly projecting forms’ [3]. There it sits, glowering, proudly declaring war upon its Victorian neighbours. But Victorianism is less reviled than it was in the 60s and 70s and the failure to unify the street now seems regrettable.

The widening of London Street at the junction with Castle Street and Swan Lane created an open space, the ‘generous 44 ft sweep’ [3] creating a latter day Norwich ‘plain’ [8]. Another one was created further east along London Street at the junction with Little Bedford Street, St Andrew’s Hill and Opie Street. Here, some years after the London Street Improvement Scheme, Boardman was to design the Eastern Daily Press Headquarters (1900).

This eclectic Arts and Crafts style is not typical of Edward Boardman’s output and may have something to do with the influence of his son, Edward Thomas [4]. The three projecting bays contain cartouches bearing dates: 1844, 1900 and 1960. The present building is of mellow stone on a dark granite base but in 1899 Boardman seems to have specified a different combination with a base made of Carrara Ware.

Developed in 1888 by the Head of Doulton’s Architectural Department, WJ Neatby, Carrara Ware was designed to imitate marble. Its weatherproof properties were exploited by George Skipper for the exterior surfaces of Norwich’s Royal Arcade, built where the Royal Hotel had stood [9]. Doulton’s records at their factory in Lambeth were largely destroyed in the Second World War, making it difficult to attribute their work to a particular building, but here we have a direct link. This photograph taken prior to the 1960 renovation shows a deep dark skirting beneath the windows that may well be the Carrara Ware specified by Edward Boardman.

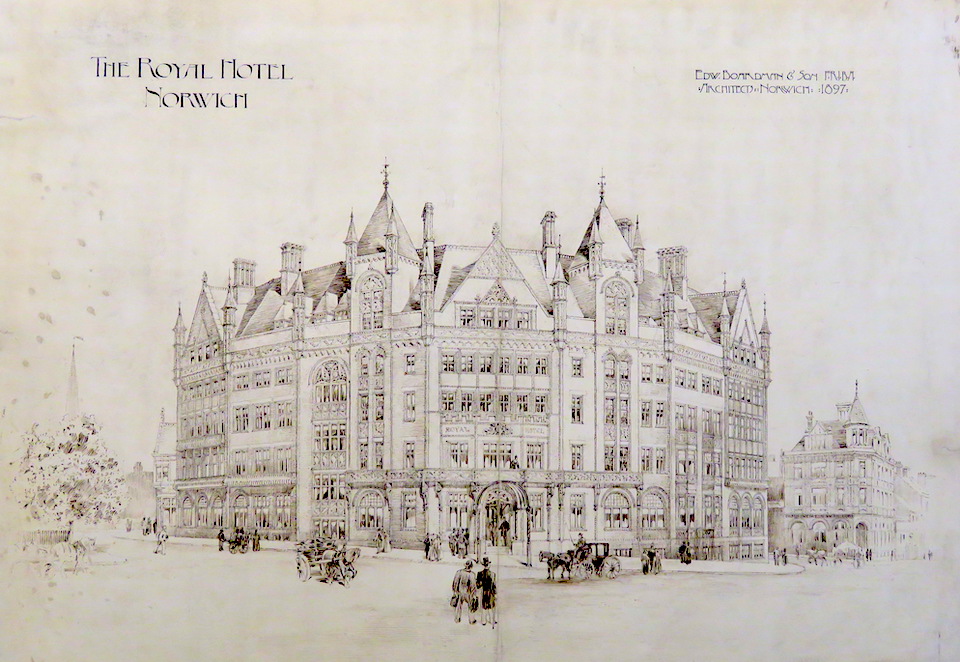

It is hard not to read it symbolically but as one Royal Hotel – a traditional coaching inn – disappeared from the marketplace another of the same name was appearing at the top of Prince of Wales, a short step from the railway station. This was the tall red-brick Royal designed by E Boardman and Son (1896-7) [10]. As with the Eastern Daily Press building, the Boardmans turned to a so-called free Flemish style for this romantic Arts and Crafts building [8].

The lower levels are unadorned, but as you gaze upwards the extravagances of the Flemish Renaissance Revival come thick and fast in the form of ornamental brickwork (here, Cosseyware) topped off with pointed gables, towers and verdigris’d pinnacles [5]. As we will see, the busyness was antithetical to the plainness of Boardman’s industrial buildings.

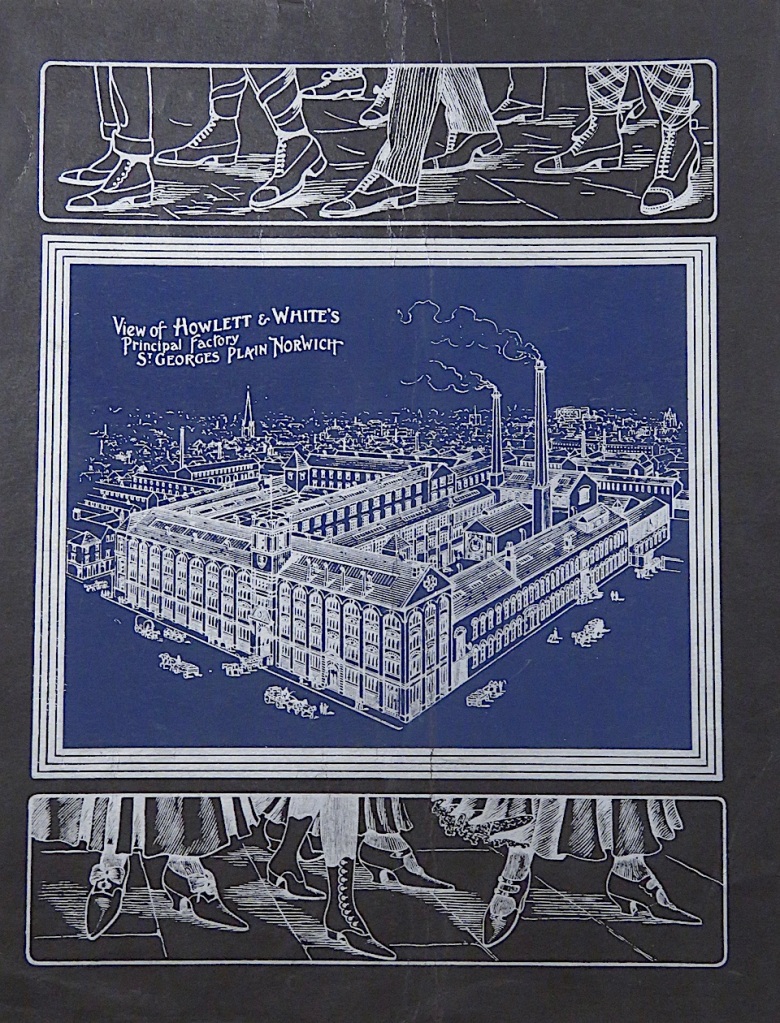

Boardman’s practice probably designed more Victorian factories and civic buildings in the city than any other (see [10] for further examples). From 1876 the firm was responsible for designing what was to become the largest shoe factory in the country; by 1911 Howlett and White’s Norvic Shoe Company on St George’s Plain, Colegate, employed 1200 workers. This statistic holds a certain irony, for the production of factory-made shoes was now the major source of the city’s employment, replacing weaving that had been the basis of Norwich’s wealth for centuries. One reason advanced for the failure of the wool and silk industry was the reluctance of home workers to abandon hand-weaving in favour of power looms as used in the factories of the north of England and Scotland. Now, a few generations later, Norwich workers were making shoes in factories illuminated by electric light.

In 1876 Edward Boardman drew up plans for the seven-bayed extension facing Colegate.

In 1894 he added another eight bays separated from the 1876 building by a tower. At the foot of the tower a two-storey-high opening preserved the public right of way down to the River Wensum via Water Lane.

The creation of Prince of Wales Road in the 1860s, followed by the London Street Improvement Scheme, helped the flow of traffic between Thorpe Station and the Marketplace but even more pervasive changes were needed to superimpose electric tramways upon a largely medieval town plan. Timber-framed houses were cut in half, an inconvenient savings bank disappeared, narrow roads were widened and two new streets were built [12]. The main entrance to the city from the south was via Newmarket Road and St Stephens Street; connecting this route to the railway station required the demolition of the east side of Red Lion Street and for a way to be pushed through to Castle Meadow. What arose behind the stepped-back building line of the new Red Lion Street was a thoroughfare designed by the city’s two foremost architects: George Skipper and Edward Boardman.

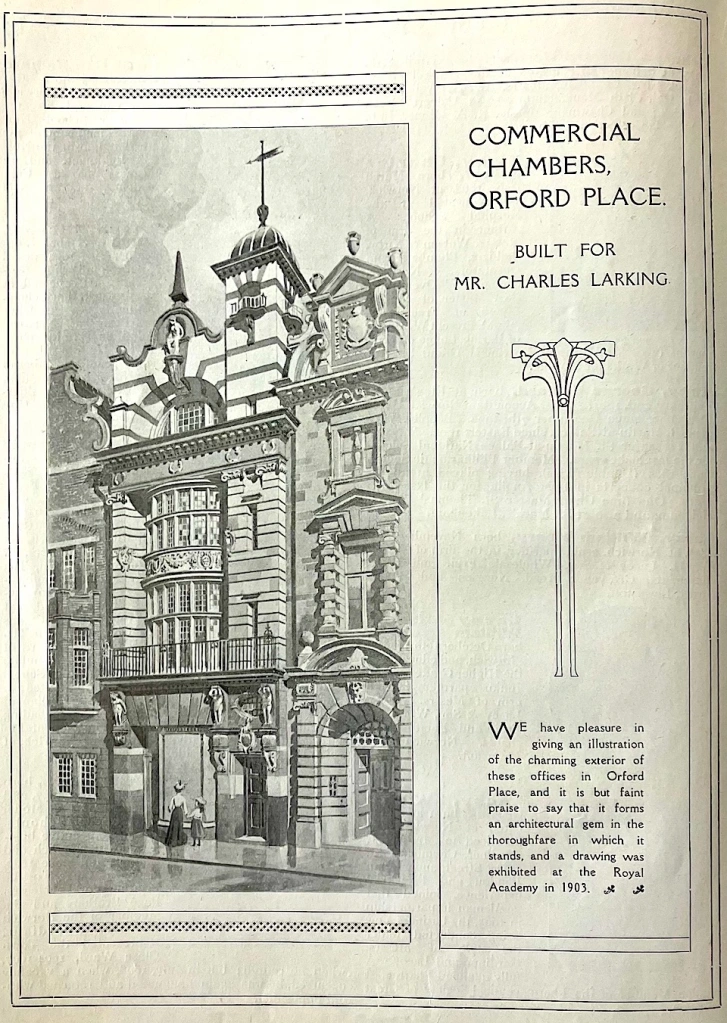

Adjacent to this was George Skipper’s Commercial Chambers. Faced in Doulton’s Carrara Ware, the narrow building is topped by a statue of the extravagantly moustachioed architect himself (for more on the flamboyant Mr Skipper see [13]). No uniformity here; the roofline is quite varied, from Pont Street Dutch to various shades of Baroque Revival.

Commercial Chambers was designed for the accountant Charles Larkin, the City Auditor, who had been Chief Clerk to Buntings, the department store where Marks and Spencer now stands [14].

Skipper also put forward a proposal for the next building along Red Lion Street – a bank.

This competition plan was never realised; in its place Skipper recycled plans for a neo-Baroque building (D, below) that had been intended for the N&N Savings Bank in Stump Cross – the part of Magdalen Street that would be erased by the flyover of the 1960s.

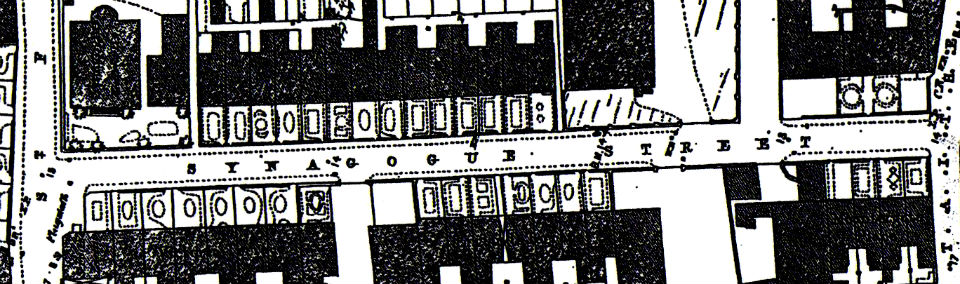

The new bank (now Barclays) in Red Lion Street was itself a replacement for another branch of the savings bank (starred below) demolished in the Haymarket in order that trams could glide more easily around the corner to the central hub in Orford Place [12]. To ease this corner, Skipper designed a curved frontage for Haymarket Chambers (now Pret a Manger) on the opposite side of the street.

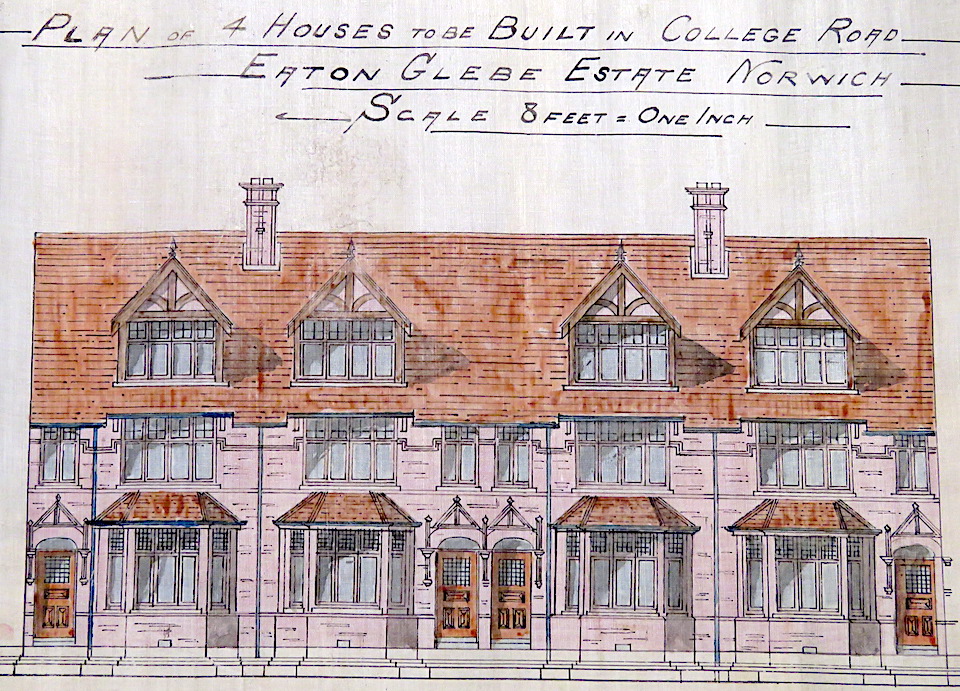

The suburbs of an expanding Victorian city were well served by the trams. The area immediately to the south west of the city had begun to fill with terraces after the sale of Unthank land in the mid-nineteenth century [15]. As a practising solicitor, Clement William Unthank had drawn up detailed covenants to preserve the appearance of terraces built on his land: to be faced in good white bricks; doorways arched in bricks; no gable peaks to the front of the house; nothing to project more than 18 inches from the building line etc. These were humble terraces whose austere frontages lent a Classical appearance. But the land on the Eaton Glebe Estate, further along Unthank Road, had belonged to the vicar of Eaton and architect Arthur Betts was free to design substantial red-brick villas in College Road with ‘the most unusual “cottagey” Gothic details’ [2], such as half-timbered attic gables and moulded brick string courses.

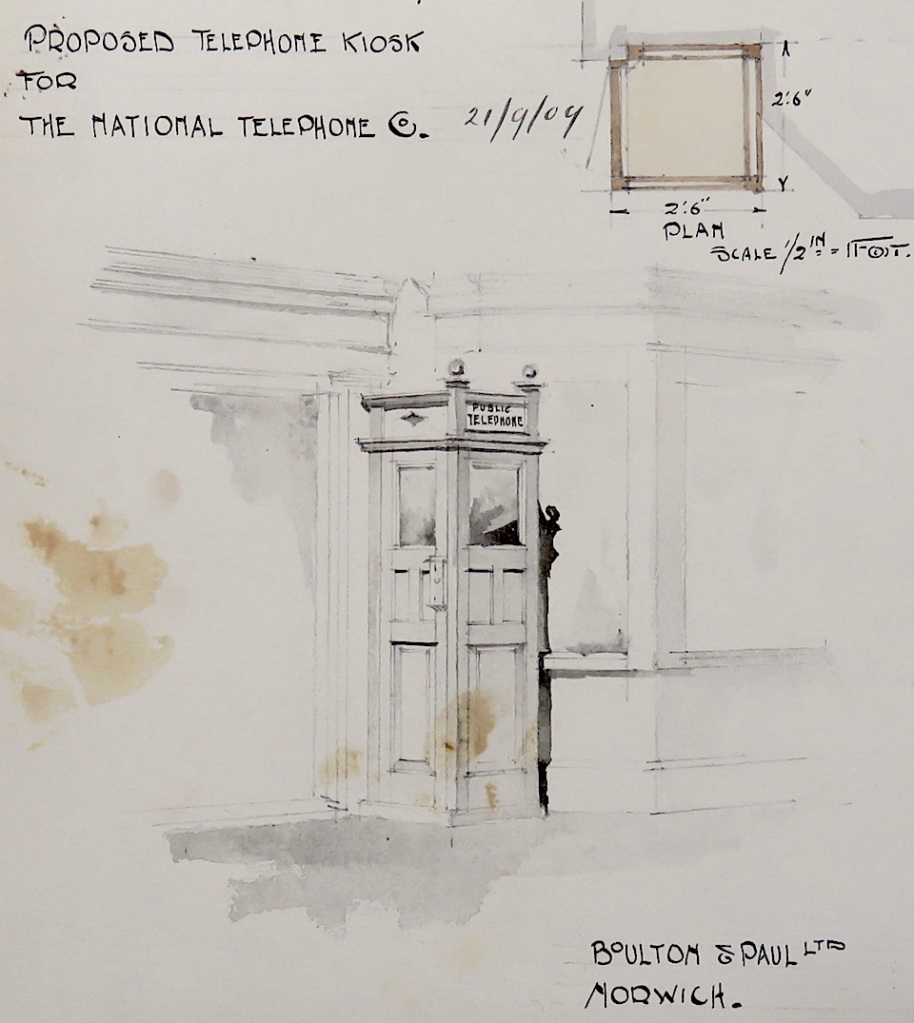

The railway and electric trams had significantly changed, not just the appearance of the city, but the lives of its citizens. Plans in the Norfolk Record Office show a structure in Unthank Road housing technology that would, over a century later, radically change the way we live now.

Thanks

It is a pleasure to thank the staff of the Norfolk Record Office for their assistance with this post. I also thank Clare Everitt for permission to use images from the invaluable Picture Norfolk website.

Sources

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2021/11/16/georgian-norwich/

- Rosemary Salt (1988). Plans for a Fine City. Pub: The Victorian Society East Anglian Group.

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (2002). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- David Bussey and Eleanor Martin (2018). Edward Boardman and Victorian Norwich. Pub: The Norwich Society.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/05/05/fancy-bricks/

- https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/018fff83-0559-3218-8041-a3dfc8000622

- https://home.barclays/who-we-are/our-strategy/backing-the-uk/east-anglia/history/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2020/10/15/norwich-city-of-the-plains/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/03/12/the-art-nouveau-roots-of-skippers-royal-arcade/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/07/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/09/15/bullards-brewery/

- Frances and Michael Holmes (2021). The Days of the Norwich Trams: Transforming Streets, Transforming Lives. Pub: Norwich Heritage Projects.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/02/15/the-flamboyant-mr-skipper/

- Citizens of No Mean City (1910). Pub: Jarrold and Sons

- Clive Lloyd (2017). Colonel Unthank and the Golden Triangle: The Expansion of Victorian Norwich. Available by mail order.

![Westlegate 20 Barking Dickey Inn COLOUR [2957] 1939-04-12.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwichdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/westlegate-20-barking-dickey-inn-colour-2957-1939-04-12.jpg)

![King St 191 Ferry Boat Inn [1286] 1936-08-16.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwichdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/king-st-191-ferry-boat-inn-1286-1936-08-16.jpg)

![Belvoir St Wesleyan Reform Methodist church [6585] 1989-09-18.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwichdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/belvoir-st-wesleyan-reform-methodist-church-6585-1989-09-18.jpg)

The yard now accommodates Loose’s Cookshop and Chez Denis cafe and brasserie. Until 1998 the owner of Chez Denis had a previous business here, Cafe des Amis, the name of which can just be made out above the central arch in the photograph below.

The yard now accommodates Loose’s Cookshop and Chez Denis cafe and brasserie. Until 1998 the owner of Chez Denis had a previous business here, Cafe des Amis, the name of which can just be made out above the central arch in the photograph below.![Red Lion St Orford Yard former stables [7536] 1998-03-10.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwichdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/red-lion-st-orford-yard-former-stables-7536-1998-03-10.jpg)

![Duke St 4 Electricity works floodlit [1633] 1937-05-13.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwichdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/duke-st-4-electricity-works-floodlit-1633-1937-05-131.jpg)