From the mid-C19th to the early C20th, the sailing ship was a common, if not central, decorative motif in the Arts and Crafts movement. It is difficult at this distance to appreciate how popular this image was but some idea of its pervasiveness is indicated by the number and range of household objects to which it was applied. The ship in full sail appears on several buildings in Norwich.

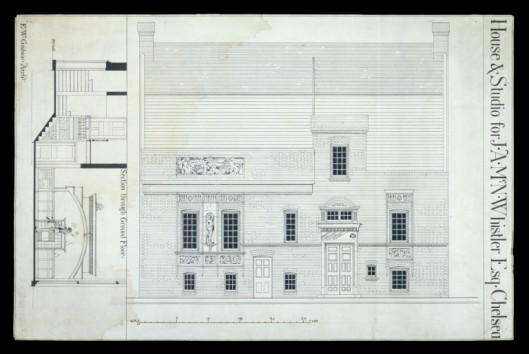

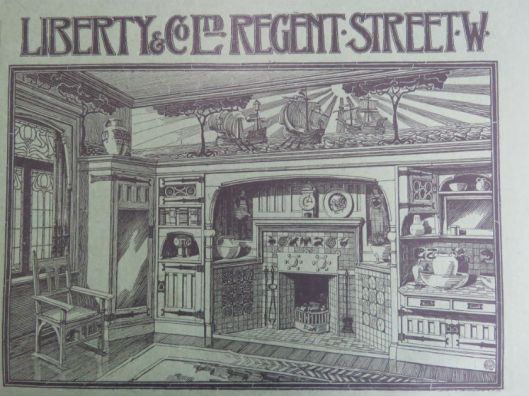

Billowing sails symbolise adventure and escape, which may explain its popularity at the peak of Victorian industrialisation. A previous blog on the Arts and Crafts house mentioned William Morris’ moral crusade against mechanisation and the revival of a medieval style unsullied by industrialisation. When it came to furnishing their aesthetic homes the middle classes, keen to display their artistic leanings, would have been influenced by magazines like The Studio. In this advertisement from that magazine, which overflows with cultural references, Liberty’s of London (“Arts&Crafts Central”) included several sets of billowing sails.

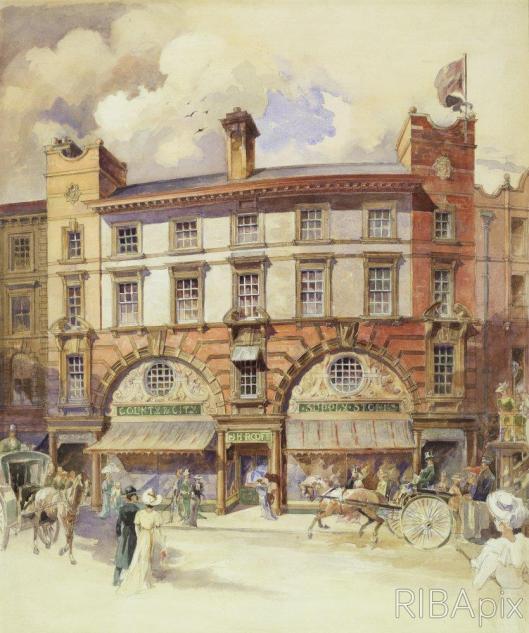

Advertisement for Liberty’s on the back page of The Studio vol 15, No68 (1898).

The Viking ship on the plate on the mantelpiece is in full sail, like the galleons on the frieze.

Most Arts and Crafts homes would have had this motif somewhere for it occurred in paintings and book illustrations, on furniture, jewellery, pottery, stained glass etc. A quick survey in a favourite Norwich shop specialising in Arts & Crafts [1] revealed ships in full sail on a wooden fire screen and on a hammered-copper clock face …

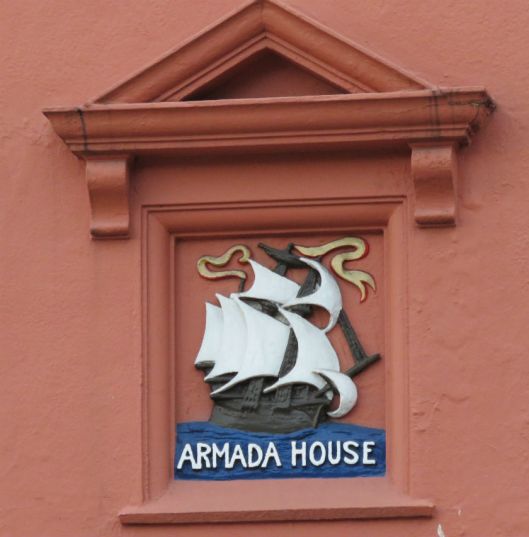

The sailing ship also appears on the building itself; it is seen here on this galleon found on a plaque on Garsett House, named after a former mayor (died 1611). It is said to have been built in 1589 from timbers salvaged from a Spanish galleon defeated in the Armada, hence the alternative name of Armada House [1].

Armada House, St Andrew’s Street, Norwich

The south wing of Armada house was cut away in 1898 to allow construction of a road carrying the new tramway [2].

Armada House on St Andrew’s Hill, opposite Cinema City. (c) Picture Norfolk

Perhaps the best known ship in the city is on George Skipper’s Haymarket Chambers, currently the home of Prêt à Manger.

George Skipper’s Haymarket Chambers 1901-2. (c) RIBApix

Not quite as depicted in this drawing, each of the two lozenges on the towers contains a large Royal Doulton tile bearing a galleon [3]. The Doulton artist WJ Neatby (of Harrods’ Food Hall fame) also designed the tiles for Skipper’s Royal Arcade nearby but although the ‘Haymarket’ sailing ship is in Neatby’s bold art nouveau style I have been unable to find evidence in Doulton catalogues that ties him to this work.

From the grandeur of the building I had thought the facade might have originally hidden a cinema but the semicircular tympani within the arches contain Doulton terracotta palms – either a reference to J H Roofe’s superior grocery stores on the ground floor or to the exotic possibilities offered by the Norwich Stock Exchange situated above the shop [4].

This beautiful stained glass panel on Tower House (below), at the junction of Kingsley and Newmarket roads, is quite similar, hinting at common influence.

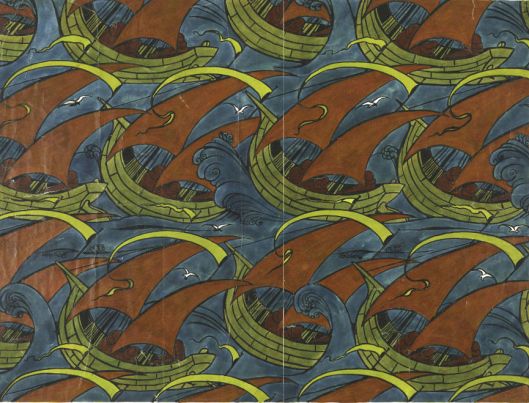

For a source of these influences we can look again to The Studio, which disseminated the designs of contemporary style-makers. Christopher Dresser, for example, was a luminary of the Arts and Crafts Movement and an 1898 edition of the magazine shows one of his fabric designs…

Christopher Dresser design for cretonne. From, The Studio vol 15 No. 68 (1898)

Charles Robert Ashbee was another artist of immense importance to the Arts and Crafts Movement and was founder of the Guild of Handicraft. The sailing ship was one of his favourite motifs and it appeared frequently in the guild’s work.

Brooch, originally a pendant, designed by CR Ashbee ca 1903. (c) V&A Images

CFA Voysey’s designs for Arts and Crafts houses were widely copied but as someone who designed contents as well as houses his influence was all-pervasive, as seen here in his design for fabric.

‘Three Men of Gotham’. Design for printed velvet by CFA Voysey ca 1889. RIBA Collections

Another key figure was Edward Burne-Jones, associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and a founding partner of William Morris’ decoration and furnishing business, Morris & Co. Burne-Jones was commissioned by Morris to design this dramatic stained-glass panel for the home of an American tobacco heiress who had been told of the Viking origins of the area.

The Voyage to Vinland the Good 1883-4. Designed by Edward Burne-Jones, made by Morris & Co. (c) Ad Meskens/Wikimedia Commons

It may be unfair to follow this technical and artistic tour de force with the ship in the window of The Gatehouse pub on Dereham Road for the building is a very late example of Arts & Crafts style (see Twinned Towers post); when the glass was installed in 1934 contemporary artists would have been more familiar with a simpler, geometric Art Deco style.

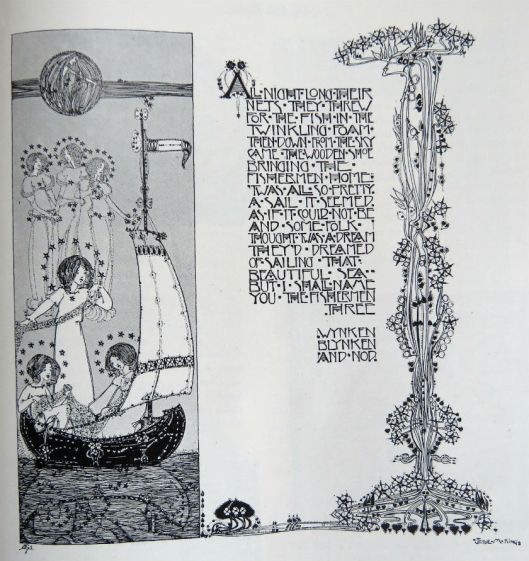

Around 1900 Glasgow was the undisputed centre for art nouveau design in Britain and Jessie Marion King was one of its leading exponents, focusing mainly on illustration. She, along with Margaret MacDonald – wife of Charles Rennie Mackintosh – was one of the ‘Glasgow Girls’ and Jessie’s feminine, curvilinear style shares resemblances with the MacDonald/Mackintosh group. The sailing ship in the illustration below does not look as ruggedly seaworthy as the Burne-Jones Viking ship but is one of countless examples of the sailing ship in children’s books, stretching to ‘Swallows and Amazons’ and beyond.

Around 1900 Glasgow was the undisputed centre for art nouveau design in Britain and Jessie Marion King was one of its leading exponents, focusing mainly on illustration. She, along with Margaret MacDonald – wife of Charles Rennie Mackintosh – was one of the ‘Glasgow Girls’ and Jessie’s feminine, curvilinear style shares resemblances with the MacDonald/Mackintosh group. The sailing ship in the illustration below does not look as ruggedly seaworthy as the Burne-Jones Viking ship but is one of countless examples of the sailing ship in children’s books, stretching to ‘Swallows and Amazons’ and beyond.

‘Wynken Blynken and Nod’ by Jessie M King. The Studio vol 15 No. 70 (1899)

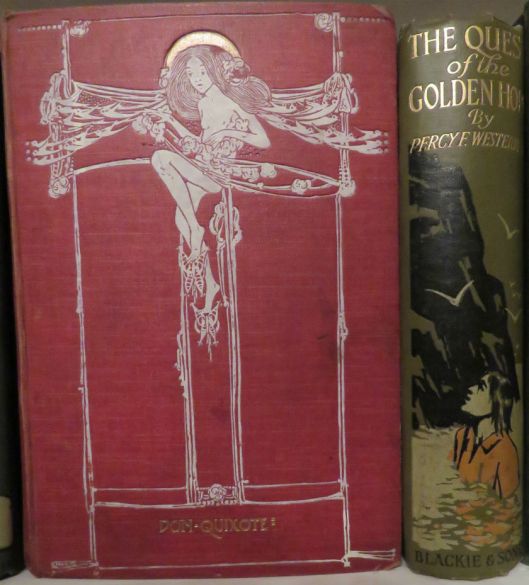

No ships in the image below – just an excuse to show one of Jessie King’s beautiful book covers.

From her ‘Three Ages of Woman’ designs, Jessie M King’s cover illustration for George Routledge and Sons’ series of classic books

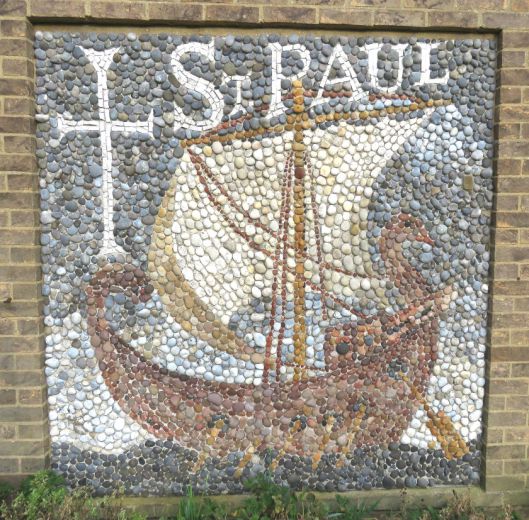

As we have seen, the ship motif was executed in a wide variety of materials, one of the more unusual being the coloured pebbles used on this post-war panel outside St Paul’s church Tuckswood, Norwich.

The last of the Norwich ‘ship’ emblems comes from Norfolk House in Exchange Street. The building – now a part of City College – was constructed after the war on the site of a furniture store that had been bombed in the Baedecker raids. Although constructed in a modern style it was intended that the building reflect something of local history and this was effectively achieved with the artwork below. The East Anglian shield is comprised of the cross of St George and the smaller St Edmund’s shield with its three golden crowns. Surmounting this is a craft that must have been a common sight into the early C20th – the Norfolk wherry whose shallow-draught allowed it to trade on the Broads.

Before the war, Raymond King and his wife had been impressed by the simple style of modern architecture in Sweden and wanted to build something forward-looking on the site. The model was the Town Hall at Halmstad in southern Sweden.

Norfolk House, Exchange Street Norwich. Taken in 1951 by georgeplunkett.co.uk

This plaque in the foyer marks the inauguration of the building in 1951, the year of the Festival of Britain that celebrated British renewal and enterprise after a debilitating war.

The bronze plaque includes the Norfolk wherry, mirroring the ship on the parapet. Like all ships with wind in their sails it projects a brighter future … and one with an appropriately local flavour.

Please let me know if you know of any other ship motifs in Norwich and Norfolk.

Sources

1.Antiques & Interiors, 31-35 Elm Hill, Norwich (www.artsandcraftantiques.co.uk)

2. georgeplunkett.co.uk. See entry on ‘Princes St 1 Garsett House’.

3. Bussey, David and Martin, Eleanor (2012). The Architects of Norwich. George Skipper, 1856-1948. Pub, The Norwich Society (available from citybookshopnorwich.co.uk).

4. racns.co.uk