Tags

Art Nouveau, Cockrill, Fastolff House, Great Yarmouth buildings, Yarmouth Hippodrome, Yarmouth School of Arts and Crafts

Two Art Nouveau buildings (and a surprising one)

If the architect George Skipper was to Norwich what Gaudi was to Barcelona (see previous blog) then, surely, RS Cockrill was to Yarmouth what Skipper was to Norwich. OK, the line from Barcelona to Great Yarmouth does seem rather tenuous but what all three architects shared was a desire to bring the new art to their native towns.

Ralph Scott Cockrill designed several buildings in Great Yarmouth with a strong Art Nouveau flavour. When researching the Royal Arcade in Norwich as an example of this style I read in Pevsner and Wilson [1] that “only two commercial buildings deserve a place in any book on the subject (The Arts and Crafts) in England: the Royal Arcade … and Fastolff House in Regent Street, Great Yarmouth…“. I didn’t know it, went to see it, and it is tremendous.

Fastolff House, Regent Street, Great Yarmouth. Built 1908, designed by Ralph Scott Cockrill.

Fastolff House is evidently named for Sir John Falstoff – Shakespeare’s Falstaff – who was born in nearby Caister Castle. The olde worlde reference is appropriate for an Arts and Crafts building that, with bands of casement windows, was designed with Norman Shaw’s Old English Revival in mind. The outstanding examples of English Art Nouveau – The Royal Arcade, Norwich and The Edward Everard Printing Works, Bristol – achieve their stunning effect with polychrome tiles designed by Doulton’s Neatby. But here, Fastolff House is covered by a facade of monochrome grey faience whose effect depends upon three-dimensional sculpturing instead of illustration.

The strongly three-dimensional moulding of the faience tiles above the front door contrasts with the low-relief tiles used in Skipper’s Royal Arcade, Norwich

RS Cockrill’s father John William Cockrill had an association with the Doulton’s Lambeth factory via his Cockrill-Doulton Patent Tiles so they seem an obvious candidate for the faience here. But Doulton’s archive has suffered over the years from fire and flood and there seems to be no record that they were associated with Fastolff House. Of course, other potteries were available. The impressive frontage of The Empire on the promenade, for instance, came from The Leeds Fireclay Company.

The decorative faience superimposed upon this Arts and Crafts building has been referred to as an “odd facade … with lively Germanic Art Nouveau” [2]. It is true that German Art Nouveau, like British, resisted the excesses of the whiplash line of France and Belgium but there are plenty of domestic sources for this restrained variant of Art Nouveau style – look no further than the front cover of The Studio …

Liberty’s of London used a wide variety of bird and tree patterns “recalling the designs of Voysey (see fabric design further down) and Knox … while others are in a typical ‘Glasgow style'”. Such Glaswegian motifs “were organic, but highly stylised, with … sinuous curves contrasting with taut, straight lines“[3]. This neatly summarises the style applied to Fastolff House.

The upper clerestory punctuated by heavily-undercut foliage around the gable. The roof tiles are green faience.

The ‘lanterns’ in the ground floor windows may be a playful reference to pre-electric illumination used in Old English buildings

The lights above the transom and the elongated stems of the flowers accentuate the proportions of the narrow side door

The ‘W’ on the beautifully patinated side door probably refers to James Williment who developed this purpose-built office block [1].

The Yarmouth Hippodrome and the Blackpool Tower Circus are the only two purpose-built, permanent circus buildings remaining in Britain. The sawdust “ring (was) 45 feet in diameter (and) is so constructed as to be converted in a few minutes to a miniature lake of 60,000 gallons of water” [4]. The original mechanism that drops the floor and floods the ring still works and currently supports a ‘live action water show’.

A busy and beautiful Art Nouveau facade but metal straps around the columns indicate the urgent need for restoration

The Hippodrome was built on the site of George Gilbert’s Circus.

George Gilbert’s Circus. Courtesy of Colin Tooke.

When constructed, Cockrill’s Hippodrome directly faced the promenade …

Yarmouth Hippodrome 1911 (c) Great Yarmouth Local History and Archaeological Society

… but later building obscured it from the road.

Yarmouth Hippodrome 2016

The decorative surface of RS Cockrill’s Hippodrome is provided by buff-coloured terracotta moulded with various Art Nouveau motifs.

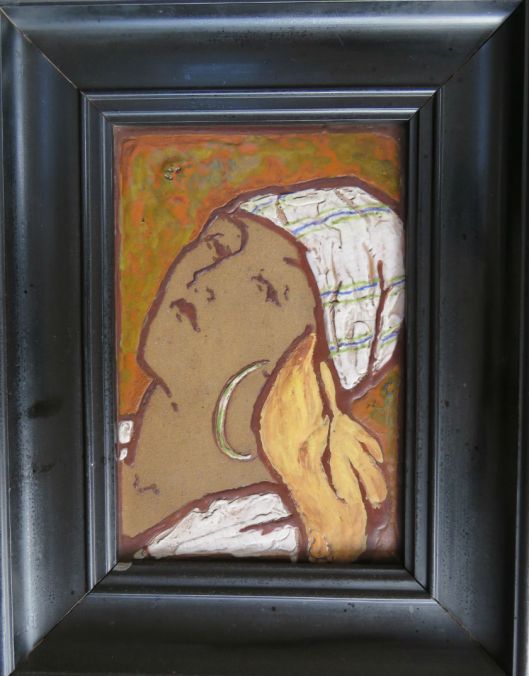

Face of a young woman crowned by a wreath of heart-shaped honesty leaves – a common art nouveau motif. This and many of the following panels require urgent restoration.

A panel of stylised peacocks (above) and a frieze of owls (below)

Left: Above the capital of honesty leaves is a panel of figures with hair in smoke-like tendrils. Right: Terracotta block depicting a tree bearing the highly stylised leaves.

The design on this terracotta panel is strongly reminiscent of work by Voysey (below). The different coloured tile cements further underline the urgent need for restoration.

Birds-in-a-tree was a favourite design of the architect CFA Voysey, which he reworked and updated in many different ways. He used these patterns on an enormous number of wallpaper and textile designs, ensuring their widespread dissemination [3].

Charles Francis Annesley Voysey. Fabric design 1898 (c) Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The previous two buildings emerged from the Arts and Crafts Movement of the nineteenth century and depend for effect on surface decoration. In the next building, by contrast, superficial decoration is suppressed (though not entirely) and looks forward to a twentieth century style of construction. The thread running through all three buildings is that they were designed by a Cockrill, except the third was produced not by Ralph Scott Cockrill but by his father John William (1849-1924). JW was born in Gorleston and was appointed to the local Board as Surveyor and (the rather Dickensian) Inspector of Nuisances. It is thought he picked up his other monicker of ‘Concrete Cockrill’ as a result of the concrete pavements he laid [5]. In 1912 he designed the School of Arts and Crafts, now restored as apartments. It is a handsome building but the local mayor ungraciously said it was “a lost opportunity with its austerely unlovely exterior“[5]. This should not be the lasting judgement because the building was an important pioneer of a new kind of architecture.

School of Arts and Crafts with its austere north facade

At about this time Walter Gropius in Germany was expounding his revolutionary ideas of a modernist architecture in which conventional load-bearing walls are replaced by columns of concrete and steel that support large expanses of steel-framed glass. His Fagus Factory (with Adolf Meyer) of 1911-13 is an icon of the modernist movement that dominated C20th commercial building on an international scale.

Fagus Shoe-Last Factory, Alfeld, Germany. Designed by Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer 1911-1913

JW Cockrill’s Yarmouth School of Arts and Crafts (1912) illustrates many of these principles: the flat roof, its steel frame, the extensive use of concrete, large expanses of glass and (for the most part) shunning of ornament mark it out as one of the first examples of modernist design in Britain.

The front facade bears the only decorative surfaces

JW Cockrill said that everything in this building was concrete except the doors … but he was working on it [5].

Sources

- Pevsner, Nikolaus and Wilson, Bill (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Yale University Press. See pages 161 and 509.

- http://tilesoc.org.uk/tile-gazetteer/norfolk.html

- Morris, Barbara (1989). Liberty Design. Octopus Books Ltd.

- Kelly’s Directory of Norfolk 1904, page 45.

- Summers, David. The Building Cockrills of Yarmouth. Norfolk Historic Buildings Group Newsletter No25 Spring 2013. pp7-8.

I am grateful to David Summers, Judith Martin and Colin Tooke for their helpful advice.