Carved monuments found in churches provide a remarkable public record of changes in fashion, politics and religion. A year ago I wrote about Norwich physician and author, Sir Thomas Browne (d.1682), and managed to track down the site of his garden house with the help of a drawing by former Head of the School of Art, Noël Spencer [1]. Spencer was an enthusiastic botherer of church sculpture and I searched for one of his out-of-print books, Sculptured Monuments in Norfolk Churches, published by the Norfolk Churches Trust [2]. Here, I followed in some of his footsteps and made a few of my own.

“But man is a Noble Animal, splendid in ashes, and pompous in the grave, solemnizing Nativities and Deaths with equal lustre …” (Sir Thomas Browne, from Urn Burial)

Until the 12th century, only clerics were allowed to be buried within the church [2]. After this, the highborn could be represented as three-dimensional figures lying upon their tomb chests. Here is Sir Roger de Kerdiston (1337) on his bed of rocks, legs crossed. Crossed-legged knights were in fashion between the mid C13 to the mid C14. Of around 350 remaining knight effigies, 200 exhibit the cross-legged pose [3].

Sir Roger’s arms are also crossed. His right hand is stretched uncomfortably across his chest to grasp his sword, as if ready to battle with death. Over the years, crossed legs have been taken to mean that the knight went on a crusade with the number of expeditions signified by where the legs were crossed (ankle, knee or thigh). This may have been an invention of the sixteenth century [4].

At Ashwellthorpe, Sir Edmund de Thorp and his wife Joan lie at rest, their hands at prayer. Alabaster is easier to sculpt than marble, allowing fine details of contemporary fashion to be recorded. Here, on the Thorp tomb, Dame Joan wears her hair in a reticulated headdress in which the elaborate side nets have not quite evolved into the even more fanciful horns and hearts of the coming century. And, just visible at the top of the photograph, the knight wears around his helmet a decorative circlet or torse – a vestige of the rolled cloth that once provided a pad beneath the helm. You may recall the torse from an earlier post on angel’s bonnets [5].

A different kind of prestige monument, a one-off, was erected in St Andrew Hingham to Thomas, Lord Morley (d. 1435), Lord of Hingham and Lord Marshall of Ireland. Made of alien red sandstone it runs from floor to ceiling on the north wall of the chancel. Pevsner and Wilson thought it, ‘one of the most impressive wall monuments of the C15 in the whole of England … like no other.’ They suggested it was based on the Erpingham Gate to Norwich Cathedral, sponsored in 1420 by Sir Thomas Erpingham, captain of the archers at Agincourt.

In the early sixteenth century, church building and renovation were dominated by the final phases of Gothic architecture – the Perpendicular and Tudor. Although the impact of classically-influenced Renaissance architecture would not be fully felt in England until the reign of Elizabeth I, elements of Italian Renaissance style appeared during the reign of the Tudor kings. The most famous example is Henry Tudor’s tomb designed by Pietro Torrigiano and commissioned by his son, Henry VIII, for Westminster Abbey. Here, in a separate work, is Torrigiano’s terracotta bust of Henry Tudor, based on a death mask.

Some of the finest early sixteenth century East Anglian tombs are in terracotta, a material made fashionable by visiting Italian craftsmen. According to Mortlock and Roberts [6] the two finest terracotta tombs of their type in England are to be found in St John Evangelist, Oxborough, in west Norfolk. These are in the Bedingfeld chapel that commemorates Lady Margaret Bedingfeld and her husband Sir Edmund, Marshal of Calais. The construction of the chapel, with its modish terracotta tombs, was willed by Margaret in 1513 but the date of its completion is uncertain. Instead of the pinnacles and pointed arches of the Gothic, the Bedingfeld tombs illustrate the revival of Greco-Roman architecture, represented here by the numerous pilasters, or flat applied columns.

The craftsmen responsible for the Bedingfeld monuments are also thought to have made the tomb chest in Norwich’s St George Colegate for Robert Jannys, mayor in 1517 and again in 1524 [7]. On the front of the tomb, baluster pilasters with Ionic capitals separate low relief decorative panels, the central one bearing the merchant’s mark for a man who made his money as a grocer. This is more easily deciphered from the photograph taken 44 years ago by Noël Spencer [2] for the fire-skin on the terracotta seems to have discoloured in the meantime.

Stylistically, Mayor Jannys’s tomb chest bears some resemblance to the later monument to the Third Duke of Norfolk (d 1554), premier Earl Marshal of England – the man who snatched the chain of office from around the neck of Thomas Cromwell. The Howards had absented themselves from Norwich and so the duke’s much grander tomb is not to be found in Norfolk but at St Michael’s Framlingham, Suffolk. (For the troubled relationship between the Dukes of Norfolk and the city of Norwich see [8]). Thomas Howard was not buried alongside his second wife, from whom he was estranged, but his first wife Anne Plantaganet, daughter of Edward IV.

Both tomb chests share arcaded panels with round-headed arches separated by Early Renaissance balusters but it is the presence, and the quality, of the figures that elevates the Duke of Norfolk’s tomb – the figures in the panels are ‘carved as beautifully as the best French work’ [9].

I never tire of visiting the many treasures of SS Peter & Paul at East Harling. Beneath the canopy lie the alabaster tomb effigies of Sir Thomas Lovell (d 1567) and Dame Alice, his wife. The Renaissance influence can be seen in the strapwork pilasters that frame the inscriptions and the three Corinthian columns bearing the canopy. The tomb-chest itself is dense with shields but in contrast to the chivalric ostentation, the two figures are dressed in plain black. Each has a crest at their feet: he has peacock’s feathers, she has a gruesome saracen’s head held aloft. The canopy, or baldacchino, over the tomb may derive from the tented catafalque on which the dead were carried to church along with their armorial bearings [2].

The red squirrel seen on the Lovell shield above is also secreted amongst the magnificent collection of C15 Norwich School glass in the east window. It was probably this that led glass expert David King to suggest that the unknown woman in one of Hans Holbein’s paintings could be Anne Lovell, wife of Sir Thomas Lovell who attended Henry VIII’s court. Known as A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling, she holds a red squirrel while the starling at her shoulder is an obvious pun on East Harling.

For 150 years before the Coke family built Holkham Hall, they buried their dead in the mausoleum outside the church in Tittleshall St Mary – a small village in the west of the county. Following the break with Rome, and the consequent changes in religious practice, the rood screen no longer marked a hard border between nave and chancel and the monuments of the titled and wealthy crept into that part of the church once reserved for the clerics. Nowhere is this better illustrated than in Tittleshall St Mary where the richness – even the colour – of the chancel contrasts with the severity of the nave. Reputedly the finest monument in Norfolk was raised to Sir Edward Coke’s first wife Bridget, a Paston. Sir Edward has a separate tomb and Bridget occupies the niche alone, with her children at prayer below, all facing east.

Founder of the family’s fortune, Sir Edward Coke, was the Lord Chancellor who prosecuted the Earl of Essex, Sir Walter Raleigh, and Guy Fawkes and his co-conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot. When he was made the first Lord Chief Justice it was hoped that this independently-minded man – a staunch supporter of parliament and the common law – would bend to the will of King James I but he refused and was dismissed in 1616 [10].

The attitudes of the figures on the monument illustrate the conventions for depicting life and death. The effigy on the tomb chest shows the man at rest, recumbent, hands held in prayer as he awaits resurrection. By contrast, the Four Virtues on the broken pediment – sitting in poses described [6] as lolling (or as my mother would say, lounging about) – show signs of drowsy activity. The seventeenth century was a period of great experimentation, not only in the attitudes of figures for the same applied to the tomb surrounds. As shown by the Coke monument, there was a general, if erratic, progression from the strapwork, skulls, hourglasses, scythes etc of the Jacobean period towards a purer Classical style [2].

A pupil of Stone’s, Edward Marshall, sculpted the Peck tomb in St Peter, Spixworth, not far from Norwich International Airport. Despite lacking the dignity of the Coke tomb, Noël Spencer thought that it the more exciting [2]. Unusually, the effigies of William and Alice Peck show both in their shrouds, rather than their finery. There is no pretence that they are as they were in life. As Pevsner and Wilson [7] wrote, they are ‘represented naturalistically as dead’.

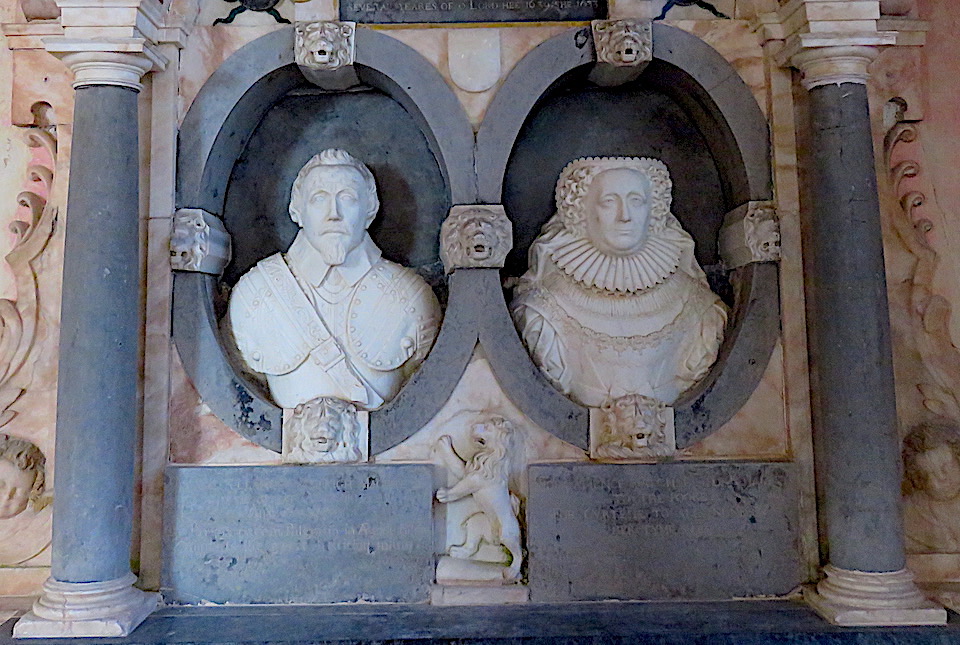

At about the same time, Sir Austin and Lady Elizabeth Palgrave were memorialised in North Barningham, not in unflinching death, but as busts that portray them in their living pomp. ‘He is bearded and faintly quizzical; she will brook no nonsense’ [12]

The Pastons illustrate the rise of the common man in the late medieval period, from someone so poor that he rode to the mill sitting on top of his corn, to the end of the line who died as Second Earl of Yarmouth (d. 1732). (To read about the Paston family in Norwich see [11]). On his tomb-chest in North Walsham, Sir William Paston (d.1608) lolls with head in hand. This ‘not dead, just resting’ pose was mocked by Bosola in Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi when he said, ‘Princes’ images on their tombs do not lie … seeming to pray up to heaven; but with their hands under their cheek, as if they died of the tooth-ache.’

And in Much Ado About Nothing, Shakespeare wrote that, ‘If a man do not erect in this age his own tomb ere he dies, he shall no longer live in monument than the bell rings and the widow weeps.’ Sir William arranged for his majestic tomb to be built by London sculptors Key and Wright at a cost of £200 [2]. Flanking the armorial tablet are obelisks (an Egyptian motif) and flaming urns, both signifying eternal life.

Sir William’s grandson and widow are commemorated in St Margaret’s church in the village of Paston. Dame Katherine Paston (d. 1629) was the daughter of Sir Thomas Knyvett who had discovered Guy Fawkes’ trail of gunpowder in 1604. Her tomb by Nicholas Stone cost an astounding £340 [12].

Below, Thomas Marsham (d.1638) lounges on a cushion, much as Dame Katherine Paston had done since 1629, yet it is Marsham’s later tomb that Noël Spencer describes as the first in Norfolk to represent the Resurrection theme [2]. This description echoes Pevsner’s [7], who writes: ‘Effigy comfortably semi-reclining, though in his shroud, as if attempting a resurrection – an early case of this attitude in England and certainly the first in Norfolk’. In terms of implied exertion there is little to separate the two effigies but the dress provides important clues. Dame Katherine is represented as a living figure clothed in her finery, a matron reclining at a Roman feast. Marsham, on the other hand, is dressed in his burial shroud and we are to assume that he is – eyes open – awakening to the trumpet call of the angels announcing Resurrection Day.

The majority of men of this period are portrayed as bearded but Marsham appears to have been retrospectively given facial hair, perhaps to prevent him looking too effeminate [13]. The graffiti is as crude as a moustache on the Mona Lisa. The monument is also notable for the realistic bones of the charnel house carved into the base of the alabaster tomb.

A more convincing depiction of resurrection appears in All Saints, East Barsham. By comparison with Marsham’s torpor, Mary Calthorpe is a positive jack-in-the-box. Married at 16 and dead aged 33 she responds to the trumpeting angel, the words on the side of her coffin exhorting, ‘Come Lord Jesu, come quickly’.

‘Kneeler’ monuments, of the kind we saw for Bridget Coke, flourished from approximately the middle of the sixteenth century through the first half of the next. During the sixteenth century it became increasingly common to find monuments in which a kneeling husband and wife face each other across a prayer desk with their children ranged behind them. On early kneelers the clear message was that prayers were being sought to speed the passage of the deceased through Purgatory [14]. But after the rejection of the doctrine of Purgatory, the iconography is suggested to emphasise status, lineage, and continuity of the family. Wilson and Pevsner describe the kneeling monument as ‘a Renaissance newcomer from France via The Netherlands’ [7].

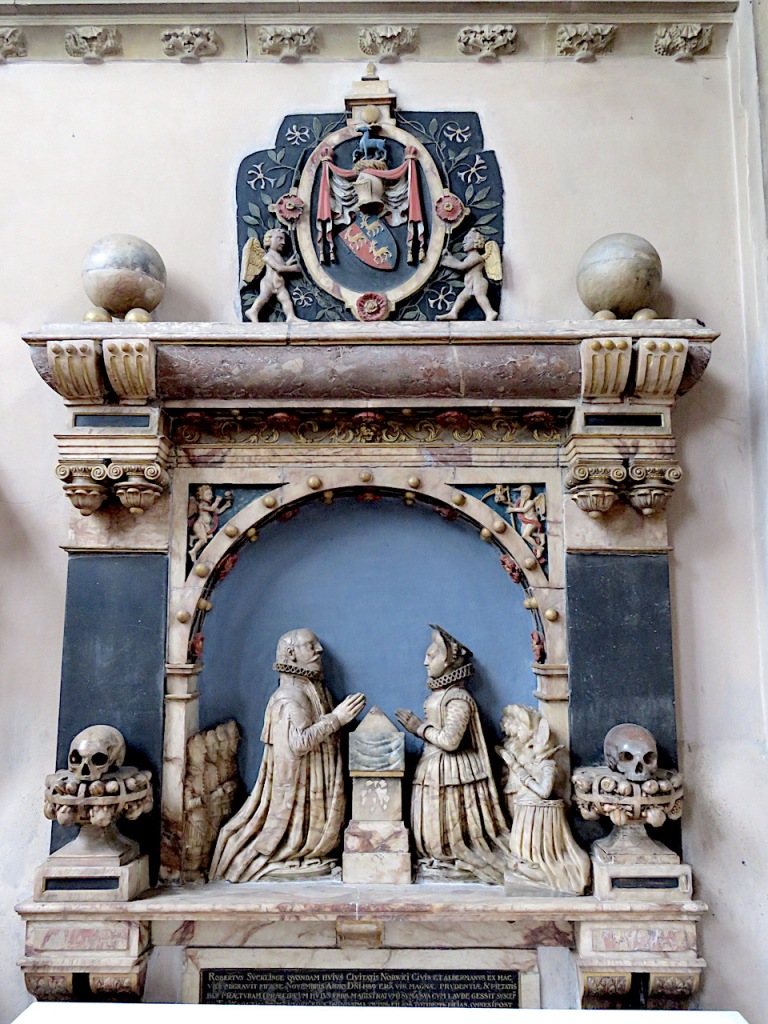

Norwich, home to many immigrants from the Low Countries, has some wonderful examples of kneeler monuments. At a time when families were large, rules of proportion and perspective had to be relaxed in order to accommodate all the children on the monument. St Andrew’s Norwich contains the tomb of Sir Robert Suckling (1520-1589); the son of a baker he became a rich mercer, alderman, sheriff, mayor and twice MP for Norwich. Here he is with his third wife and five daughters and five sons from his first marriage. Suckling’s town house survives as part of Cinema City.

Another tomb in St Andrews bears effigies of Sir John and Lady Suckling (d 1613), the son and daughter-in-law of Sir Robert. Sir John was James I’s treasurer and the richness of his monument is in keeping with his high office. His four daughters kneel in prayer on the front of the chest. The tomb itself is open, with the lid supported on four skulls, demonstrating that chest tombs are ‘merely empty boxes designed to raise the memorial up to eye level’ [2]. To the right of the inscription is a bird escaping its cage, signifying the release of the soul [2]. ‘Our soul is escaped as a bird out of the snare of the fowlers: the snare is broken and we are escaped‘ (Psalm 124:7).

Norwich and its freemen had long enjoyed a greater than usual degree of civic independence granted by the Crown. This, together with a general shift in the balance of power brought about by the Protestant Reformation, ensured that monuments to the rich and powerful mercantile elite – and not just those who were high-born or gained national prominence – started to appear in greater numbers in the city’s churches.

Here, in St George Tombland, is the memorial to alderman, speaker of the council and mayor Thomas Anguish (1538-1617) at whose mayoral inauguration 33 people were crushed to death after the crowd tried to escape exploding fireworks [15]. His monument is by Nicholas Stone who celebrates neither royalty nor aristocracy but a grocer in his red mayoral robe. Note the nine sons and three daughters. Only the five sons not holding skulls survived the parents while two of the sons are swaddled chrysoms, who died soon after birth.

The Anguish memorial is also notable for being a hanging monument; it occupies no floor space, with the sad corollary that it is now hardly visible, squashed behind the organ. Wall monuments proliferated after the Reformation as we will see in the next post.

To be continued …

© Reggie Unthank 2021

Sources

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2020/07/15/thomas-brownes-world/

- Noël Spencer (1977). Sculptured Monuments in Norfolk Churches. Pub: Norfolk Churches Trust.

- Rachel Dressler (2000). Cross-legged knights and signification in English medieval tomb sculpture. Studies in Iconography vol 21: 91-121.

- http://the-history-girls.blogspot.com/2016/02/cross-your-legs-and-hope-to-die-what.html

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2020/06/15/the-angels-bonnet/

- D.P. Mortlock and C.V. Roberts (1985). The Popular Guide to Norfolk Churches. No 3 West and South-West Norfolk. Pub: Acorn Editions.

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk I: Norwich and North-East and 2: North-West and South. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/12/15/the-absent-dukes-of-norfolk/

- James Bettley and Nicolaus Pevsner (2015). The Buildings of England. Suffolk: East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edward-Coke

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/12/15/the-pastons-in-norwich/

- D.P. Mortlock and C.V. Roberts (1985). The Popular Guide to Norfolk Churches No 1 North-East Norfolk.

- http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/strattonstrawless/strattonstrawless.htm

- Sally Badham (2015). Kneeling in prayer: English commemorative art 1330–1670. British Art Journal vol 16: 58-72.

- http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk/monuments/Thomas%20Anguish/Thomas%20Anguish.shtm

Thanks

I thank Simon Knott for supplying the de Thorp photograph. I am also grateful to John Bayliss, Christopher Howse and Anne Oatley for comments, and to The Rector of St Andrews for opening the church.

Thank you, Reggie, as always fascinating, your blog

and these monuments.

Eva, from Stokkum’s paradise (North Holland).

LikeLike

There must surely be the Dutch equivalent? Please let me know.

LikeLike

Thanks for a superb piece of research

LikeLike

Appreciate the kind comment, John

LikeLike

So interesting , wish I had come on your outings. Hope to see you once the silly season is over. much love Jayne xx

LikeLike

There are plenty more to cover, still. Reggie

LikeLike

What a wonderful page!

LikeLike

So pleased you like it!

LikeLike

A splendid post on an often overlooked aspect of our churches. I look forward to more on this subject.

Keep a’troshin bor

Don Watson

LikeLike

As I write, just putting the finishing touches to the next post on this subject. Thanks Don

LikeLike

As a person whose hobby is photographing Norfolk churches inside and out, I found this fascinating.. I am not even half way through yet. I just wanted to point out that the family at Oxburgh (sic) Hall, whose memorial chapel is in Oxborough (sic) church, is Bedingfeld, not Bedingfield. Looking at my photos, I see that this spelling is used on all the monuments so I’d presume it should also be called the Bedingfeld chapel.

LikeLike

Thank you Jeremy. Aren’t we fortunate to live in such a historically rich county? Yes, I had clocked the distinction between Oxborough/Oxburgh. But opinion seems split on Bedingfeld/Bedingfield: some sources hedge their bets with ‘Bedingfeld or Bedingfield’. The family is said to have descended from Bedingfield in Suffolk where the Late Medieval lords of the manor were Bedingfields. I see that Mortlock and Roberts, in their guide to Norfolk churches, and Simon Knott (of the great norfolkchurches site) use Bedingfield. On the other hand, Noël Spencer, Pevsner and the National Trust prefer Bedingfeld. I don’t remember inscriptions on the two tombs but I will happily make the correction if you assure me that Bedingfeld was used. Kind regards, Reggie

LikeLike

Thank for your detailed response. I checked my copy of Mortlock and Roberta Guide to Norfolk Churches before posting my comment. It’s 2nd edition 2007 and uses Bedingfeld throughout the entry.

LikeLike

My Mortlock and Roberts edition is 1985 and uses Bedingfield. I’ll therefore follow their lead in the 2007 edition and use Bedingfeld. Thanks for pointing this out.

LikeLike

Really fascinating. And I see you have ventured a little beyond the limits of Norwich too. The churches are amazing throughout the county. I was , for a while, obsessed with Simon Knott’s Norfolk Churches website.

LikeLike

Hi Daniel, Yes, I do get out of Norwich for the annual outing. Norfolk churches are indeed amazing and Tittleshall is a stunner. I approve of your obsession with Simon Knott’s website. What a resource.

LikeLike

Reggie,

Splendid post, looking forward to the next one!

Norfolk has so much to offer, high time we paid an other visit,,,,

LikeLike

Hi Maarten, The Dutch influence even affects Norfolk church monuments. Look forward to seeing you back in Norfolk. Reggie

LikeLike

What a fabulous post, Reggie! Thank you so much for all your research and the wonderful photos.

LikeLike

Thank you Clare. I have had great enjoyment in visiting (often re-visiting with a fresh eye) these churches. I’ve enough material for multiple posts but will only inflict another one on you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Sculptured Monuments #2 | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Noël Spencer’s Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Norwich Guides: Ancient and Modern | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Thank you for this very interesting article. Lady Joan’s headdress is a crespine.

LikeLike

Thank you Jonathan. The sculptor did an outstanding job in depicting net in alabaster.

LikeLike