Tags

My Lord's Gardens, Pablo Fanque, Pleasure gardens, Quantrell's Gardens, Ranelagh Gardens Norwich, The Wilderness Norwich, Vauxhall Gardens Norwich

For over 200 years, Norwich’s pleasure gardens provided public recreation, from bowls and leisurely walks in the C17th to Pablo Fanque’s Fair in the C19th.

Pablo Fanque and steed from The Illustrated London News

I ended the previous post with a passing mention of My Lord’s Gardens, a relic of the Dukes of Norfolk. Here it is, on Samuel King’s map of 1776, some 100 years after the gardener and diarist John Evelyn designed it for Henry Howard who – now that the dukedom had been restored by Charles II – was keen to re-establish his family’s presence in Norwich. This was to be the first of several pleasure gardens in Norwich.

Between King Street and the bend in the river opposite the modern-day railway station were My Lord’s Gardens (outlined in red, the name underlined in green) and Spring Gardens (blue). From, A New Plan of the City of Norwich, by Samuel King 1766. Courtesy Norfolk Museums Service.

The Sixth Duke rebuilt his family’s frequently-flooded riverside palace near the present-day Duke St Car Park [see previous post] and, to compensate for its lack of recreational space, Evelyn was to lay out a garden on the other side of the city. Around 1663 the duke paid £600 for a plot on the site once occupied by the Austin Friars. This plot off King Street was to become the first pleasure garden outside London. Throughout the 1700s Norwich was one of a handful of cities, like Bath and Tunbridge Wells, where the rising ‘middling rank’ could enjoy provincial imitations of London’s fashionable pleasure gardens [1].

Dr Edward Browne (son of philosopher Thomas Browne) said My Lord’s Garden contained: “a place for walking and recreations, having made already walkes round and crosse it, forty foot in breadth. If the quadrangle left bee spatious enough hee intends the first of them for a fishpond, the second for a bowling green, the third for a wildernesse, and the forth for Garden.”

In 1681 Thomas Baskerville arrived at the garden by boat and ascended ‘some handsome stairs’ to be served ‘good liquors and fruits’ by the gardener. He saw a fair garden with a good bowling-green and many fine walks. We have no image of the garden in those early days and must glean what we can from later maps. Looking west towards King Street from the Thorpe side, this prospect of 1741 shows the area in the bend of the river occupied by My Lord’s Garden. The major feature is the formal parterre of what appear to be low hedges and shrubs in a ‘Union Jack’ pattern separated by densely-planted trees from the houses behind (King St). However, the map’s key reveals the barely visible ‘9‘ at the centre of the parterre to be Spring Gardens rather than My Lord’s Garden. Could the Bucks have been mistaken for none of the other maps show the smaller competitor occupying so much of the riverside leading up to King Street [1]?

Samuel and Nathaniel Buck’s 1741 prospect of Norwich from the south-east. King Street runs left-right behind the garden. NWHCM:1922.125.4:M

Perhaps the gentlefolk surveying the city from high on the east bank would have been the sort of clientele attracted to My Lord’s Garden in the C18.

Fifty years later, well after the Dukes of Norfolk had retreated to Arundel in Sussex, the portion of My Lord’s Garden closest to Howard House (red star) appears as a cluster of rectangular gardens with a large lawn. The bowling green was still around in 1770 [1], so might the rest of the now-public garden also adhere to the original plan or had it become kitchen gardens?

My Lord’s Gardens (red) in 1789. Red star marks Howard House now being restored on King Street. Spring Gardens in blue, with the octagonal Pantheon marked with a blue star. Anthony Hochstetter’s map courtesy of Norfolk Record Office.

In 1772 the owner of My Lord’s Garden tried to outflank his newer competitors by building an artificial cascade modelled on the one at London’s Vauxhall, for public gardens now featured performance. There, water cascaded down to turn a watermill; the sound of rushing water was made by ‘mechanics’ turning a wheel to which tin panels were attached, making a noise that was sufficiently realistic to impress Charles Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus [2]. Norwich claimed a better cascade with the addition of swans while the sun and moon were made to move across the sky.

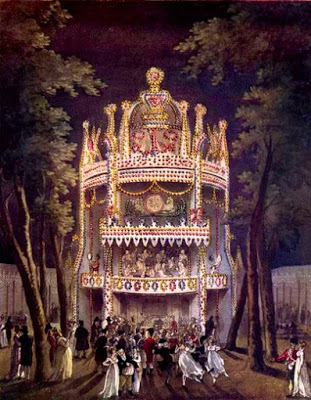

Vauxhall Gardens, from The Microcosm of London (1808-10). Courtesy [2].

The only remaining vestige of My Lord’s Garden may be the wall on King Street, which George Plunkett [3] suggested to be the original boundary wall of the Austin Friars.

Howard House. Left: http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk 1934; right, 2018. The gateway has been walled in but the same pattern of tumbled-in stone remains in the flint wall to the left.

In 1739, John Moore designed the neighbouring New Spring Gardens as a place where ladies and gentlemen could promenade or take a pleasure boat and enjoy wines and cider, cakes and ale.

Map of Spring Garden(s) by City Surveyor WS Millard, early 1800s. The inlet was the East Creek that defined a boundary. Courtesy Norfolk Record Office

Moore named his garden after London’s New Spring Gardens [1], which were mentioned by Samuel Pepys and later – when renamed Vauxhall – visited by Becky Sharpe in Vanity Fair. Following suit, Norwich Spring Gardens were renamed Vauxhall Gardens in the late C18. Initially, Moore’s was a ‘rural garden’ where people could stroll through “a very curious Transparent Arch built in the Gothick taste”, no doubt aping London’s Vauxhall. But in 1768, in response to competitors, Moore’s widow began illuminating the garden and entertaining guests with music and fireworks. Around 1776 the gardens were acquired by performer and scene painter James Bunn, which gives an idea of the increasing theatricality now expected of public pleasure gardens: what had started as a fashionable stroll had now become commodified entertainment. Bunn responded by building an octagonal 1000-seater Pantheon, named after the building on London’s Oxford Street [1].

Bunn’s octagonal Pantheon in New Spring Gardens, from Hochstetter’s map of 1789.

The Oxford Street Pantheon, designed by James Wyatt, was demolished as late as 1937 and is now the site of Marks and Spencer [4].

The Pantheon, Oxford Street, London. Probably by Wm Hodges with added figures by Zoffany. The coffering (recessed panels) in the roof copy those in the Roman Pantheon. Wikimedia Commons

Situated on the hill between Bracondale and King Street, high above present-day Carrow Bridge, The Wilderness became the city’s third public garden – leased to Samuel Bruister in 1748, [1]. His wrestling matches would have attracted a less genteel clientele but in a few years – during Assize Week when circuit judges came to town – The Wilderness had raised its sights, competing with New Spring Gardens with public breakfasts and music. In practical terms a ‘wilderness’ suited the hilly terrain but was also more in tune with ideas of naturalistic landscape expounded by Capability Brown. However, when part of The Wilderness was re-opened as Richmond Hill Gardens ca 1812 it was primarily as a venue for fireworks [5].

The Wilderness Public Gardens were just inside the city walls on the east side of Bracondale, on the hill above King Street. There was a gravelled Long Walk beneath the city walls, up to the Black Tower and the Wilderness Tower. Norwich 1789. ©The Historic Towns Trust

The Walk under the wall on top of Carrow Hill (entrance at top of Carrow Hill). The Black Tower in the distance

![Wilderness Tower and Black Tower [2190] 1938-03-21.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwichdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/Wilderness-Tower-and-Black-Tower-2190-1938-03-21.jpg?w=529)

The ‘Wilderness Tower with Black Tower behind. ©www.georgeplunkett.co.uk

Between present-day Sainsbury’s on Queen’s Road and the St Stephens roundabout the fourth pleasure garden was to become the city’s most popular.

Quantrell’s Gardens (later Victoria Gardens) on Hochstetter’s map of 1789. The circle marks present-day St Stephens roundabout, the star marks the old Norfolk and Norwich Hospital.

Widow Smith’s Rural Gardens started ca 1763 as a nursery garden [1] but when she began to illuminate the grounds on Guild Days and to sell cider and nog, she set two men at the gate to keep out disagreeable persons; she also employed William Quantrell as engineer for her firework shows and before long he owned Quantrell’s Gardens. Competition was intense: My Lord’s Garden had installed complex machinery to represent land and sea battles; The Wilderness had a “grand Piece of Machinery … to run 680 Yards upon a Line”; but Quantrell had Signor Pedralio’s “Globe 21 feet in Circumference which will turn round its Axis, and fall into four parts, and will discover Vulcan inside, who will be attended by his Cyclops … Vulcan’s (pyrotechnic) Cave and Forge and the Eruption of Mount Aetna.” When Spring Gardens poached Signor Pedralio, Quantrell’s riposte was to get Signor Antonio Batalus to “Fly across the Garden with Fire from different Parts of the Body [1].” Who wouldn’t pay good money to see that?

After the first manned balloon flight was made in France in 1783, England experienced Balloon Mania. The following year Bunn’s balloon floated quite happily inside his Norwich Pantheon, but when taken outside was quickly lost in a shower of hail.

Vincento Lunardi’s balloon in the London Pantheon. Wikimedia Commons

In 1785, Quantrell won this contest by hosting a balloon ascent by James Decker (or Deeker) with a 13-year-old girl as passenger. The balloon was damaged in a squall, Miss Weller was left behind but Decker ascended and came down safely near Loddon [1]. In his diary, Parson Woodforde mentions that the balloon passed over him as he stood on Brecondale (sic) Hill.

Courtesy Norfolk County Council, at Picture Norfolk

And it was from Quantrell’s that Major John Money made his famous balloon flight in 1785. In trying to raise funds for the nearby Norfolk and Norwich Hospital, the major took off only to be carried away by an ‘improper current’. He descended into the sea off Yarmouth in which he was immersed for seven hours before rescue [see earlier post 6].

Proto-windsurfer Major John Money, off the coast of Yarmouth.

At the end of the C18 Quantrell’s Gardens came into the hands of Samuel Neech who renamed it Ranelagh Gardens, after the pleasure gardens in Chelsea. From Canaletto’s painting of the London resort it is hard to believe that its Norwich counterpart was anything like as ambitious.

The interior of the Rotunda, Ranelagh Gardens, London. c1751 Canaletto.

Confusingly, the advertisement below places the Norwich Pantheon in Ranelagh and not at the Vauxhall/Spring Gardens but this was because Neech had bought The Pantheon from the defunct Norwich Vauxhall and erected it on his own site, to add to his Amphitheatre.

Courtesy Norfolk County Council, at Picture Norfolk

Just before Ranelagh Gardens closed it had contained a circus operated by William Darby of Ber Street, known as Pablo Fanque, whose circus was celebrated in The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper album – ‘Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite’ [7]. Rather wonderfully, his name is commemorated in the new Pablo Fanque House on All Saints Green, providing student accommodation.

Pablo Fanque House in All Saints Green, opposite John Lewis. Portrait of equestrian and circus owner William Darby aka Pablo Fanque

In 1849, Ranelagh Gardens (Royal Victoria Gardens since 1842) were closed and sold to the Eastern Union Railway Company who built platforms either side of The Pantheon.

Top left, Quantrell’s Gardens 1789; Centre, OS map of Victoria Station 1905; Lower right, Marsh Insurance Ltd C21. The St Stephens roundabout (red circle) with Queen’s Road to the right. Latter two images reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland

The Booking Office of Norwich Victoria Station 1913. Could this be The Norwich Pantheon? Courtesy Norfolk County Council, at Picture Norfolk

Other smaller pleasure gardens grew up around Norwich in the C19: some as tea gardens, some attached to public houses; e.g., The Mussel Tea Gardens in Telegraph Lane, Thorpe; The Greyhound Gardens on the east side of Ber Street; The West End Retreat, Heigham; The Gibraltar Gardens, Heigham Street – all providing breathing space from the crowded city, [8]. Prussia Gardens at Harford Bridge was a popular venue where, in 1815, balloons were still in fashion: a Mr Steward took off but only ‘skimmed and skimmed and skimmed and skimmed’, to stop 500 yards away. In WWI some soldiers removed the pub sign bearing the King of Prussia’s head, prompting the patriotic change of name to the King George. It is now the Marsh Harrier.

The Marsh Harrier PH, the site of Bensley’s Rural Gardens at the King of Prussia. Was it Glen Miller who took over the piano one night during WWII? [9].

A clue to the demise of public pleasure gardens in general can be found in the demise of Norwich’s Ranelagh/Victoria Gardens, literally subsumed beneath the railway that led to the rise of seaside resorts and changed the public’s perception of leisure.

©2019 Reggie Unthank

Now in its fourth printing, available from Jarrolds Book Department or online (click here) and the City Bookshop, Davey Place, Norwich (or click here).

Sources

- Trevor Fawcett (1972). The Norwich Pleasure Gardens. Norfolk Archaeology vol XXXV, part III pp382-399. (The well-researched standard text).

- https://www.regencyhistory.net/2015/10/the-cascade-at-vauxhall-gardens.html (An excellent blog post about The Cascade at London’s Vauxhall Gardens by Rachel Knowles).

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/kin.htm#Kings

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pantheon,_London

- Sarah Jane Downing (1988). The English Pleasure Garden 1660-1860. Shire Publications.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/12/01/entertainment-victorian-style/

- http://www.100greatblackbritons.com/bios/Pablo_Fanque.htm

- Walter Wicks (1925). Inns and Taverns of Old Norwich, With Notes on Pleasure Gardens. Pub: Page Bros (Norwich).

- http://www.norfolkpubs.co.uk/norwich/knorwich/nckge2.htm

Thanks to Jill Napier (née Quantrell) for suggesting this post about her ancestor. I am grateful to Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk for permission to use images.

Reblogged this on Tangential Ramblings.

LikeLike

Reggie,

What a pity we don’t have pleasure gardens anymore!

LikeLike

Maarten, I agree and would have loved to have seen the original Vauxhall Gardens.

LikeLike

Pingback: Late Extra: The Norwich Pantheon | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Mr Marten Pays a Visit to Norwich! – Norfolk Tales & Myths

Pingback: The Norwich Banking Circle | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Parson Woodforde and the Learned Pig | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Mr Marten Visits Norfolk! – Norfolk Tales, Myths & More!

Pingback: Georgian Norwich | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH