Thomas Jeckyll’s ‘Sunflower’ andirons – emblems of the Aesthetic Movement. (c) The Freer and Sackler Galleries, Washington DC USA. Photo: Neil Greentree

He was a key figure in the Aesthetic Movement who helped spread an esoteric fascination with japonisme to the nation, yet Thomas Jeckyll was an unsung local hero who died in a Norwich lunatic asylum. In previous posts [1,2, 3] I discussed how this son of a clergyman from Wymondham, Norfolk joined the set of London aesthetes including Whistler, Swinburne, Rosetti and fellow Norfolkman Frederick Sandys. This influenced his work back home in Norfolk where his designs for Barnard Bishop and Barnards’ Norwich Iron Works advertised the Anglo-Japanese Movement on an industrial scale.

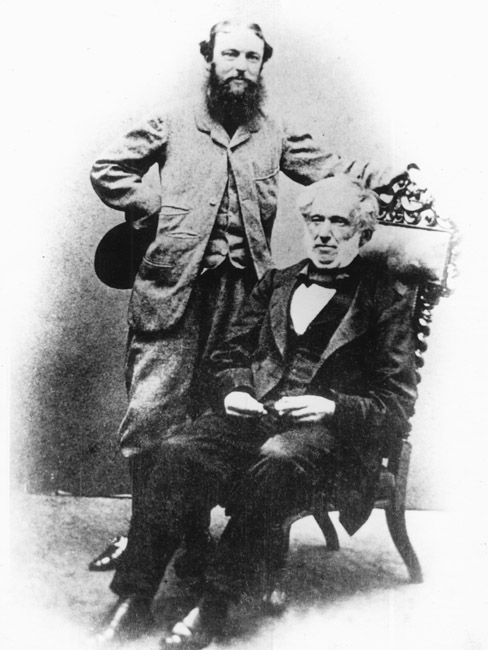

Thomas Jeckyll with his father George in the 1860s ((c) Picture Norfolk. Norfolk County Council)

Jeckyll’s first national success was with the Norwich Gates that he designed for Barnards in 1859 [4]. They took three years to manufacture and, when exhibited in the 1862 International Exhibition in London, were awarded a medal for craftsmanship; Jeckyll – who received ecstatic critical acclaim – was elevated to national attention. The people of Norfolk and Norwich bought the gates by public subscription and presented them to the Prince and Princess of Wales on their marriage in 1863. The gates can still be seen at Sandringham.

Norwich Gates, Sandringham, Norfolk (c) Museum of Norwich, Norfolk Museums Service

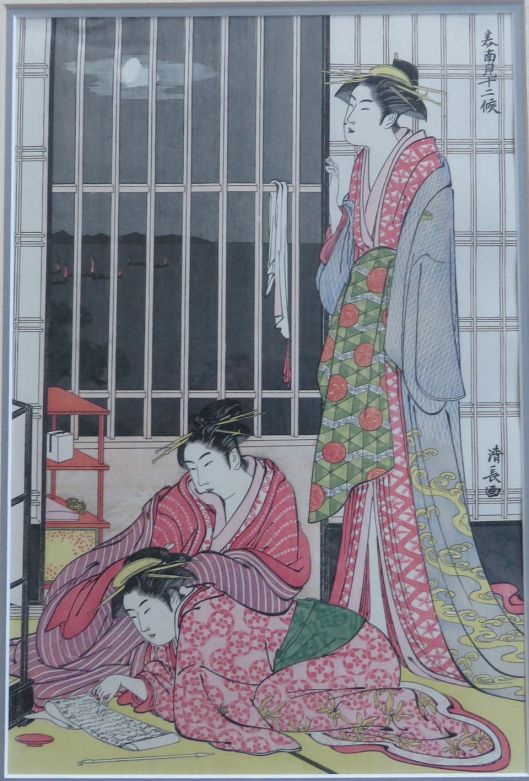

But Jeckyll’s continuing reputation was shaped by events on the other side of the world. In 1853-4 US Admiral Perry used gunboat diplomacy to force Japan out of its self-imposed isolation, opening trade with the west. The woodblock prints that emerged had an immediate impact on western art: the works of Manet, Monet, van Gogh, Vuillard, Toulouse-Lautrec, Bonnard, Cassat all showed the signs of Japanese influence, often being occidental versions of original oriental themes [5]. The unusual (to western eyes) cropping of the image, flattened shapes and planes composed of few subtle colours changed the direction of French art in the latter half of the C19th.

‘Mlle Marcelle Lender en buste’ by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1895); bust of the waitress Okita of the Naniwaya teahouse by Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806)

James McNeill Whistler, who was an avid collector of Japanese prints and pottery, is said to have been the first to bring back japonisme to this country after his return from Paris in 1860. The art dealer Murray Marks said that the artist had “invented blue and white in London” [5]. The mania for things Japanese could attract a certain preciousness; after Oscar Wilde said he was finding it hard to live up to his blue china, George du Maurier – one of Jeckyll’s London circle – pricked the bubble with this Punch cartoon:

The Six Mark Teapot (c) Punch

Aesthetic Bridegroom: “It is quite consummate is it not?”

Intense Bride: “It is indeed! Oh, Algernon, let us live up to it!”

Whistler’s own painting was changed by his exposure to Japanese art. His well known nocturne of Old Battersea Bridge certainly borrowed strongly from Hiroshige’s print of Kyobashi Bridge, part of his One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (as Tokyo was called).

Utagawa Hiroshige, Kyobashi Bridge 1857: James McNeill Whistler, Old Battersea Bridge 1859

While the fashion for things oriental was originally confined to a metropolitan elite, where it developed out of their interest in the fine arts, it soon became a widespread phenomenon of the applied arts [5]. The influential decorative arts designer Lewis F Day recognised that Jeckyll’s work was amongst the first to show this Japanese influence [4]. Art dealer Gleeson White wrote that Jekyll was:

the first to design original work with Japanese principles assimilated – not imitated [6]

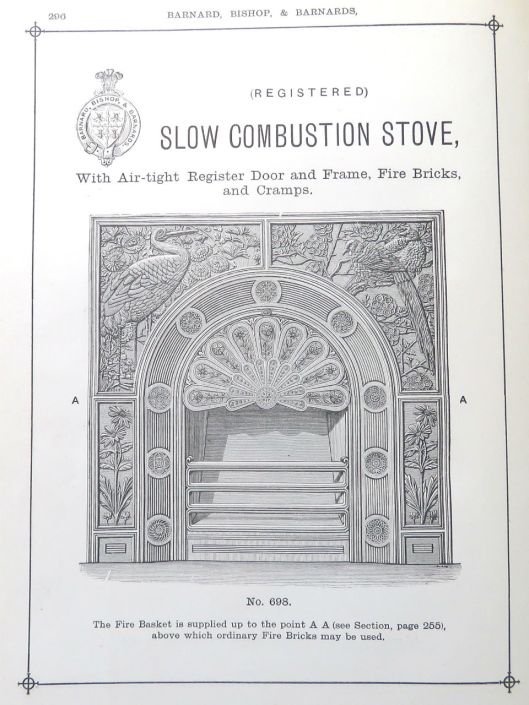

As designer for Barnards at their Norwich foundry, Jeckyll was able to spread japonisme and he did this largely via the Great British Fireplace (coming soon to BBC1). From ca 1870 Barnard Bishop and Barnards produced numerous japonaise designs into which Jeckyll skilfully introduced cranes, cherry blossom, chrysanthemums, sunflowers etc.

Designed by Thomas Jeckyll From Barnards’ 1884 catalogue. (c) Museum of Norwich, Norfolk Museums Service

Japanese heraldic roundels or mon also became a recurring motif in Jeckyll’s designs, providing a ready shorthand for japonisme.

Jeckylll fireplace (c) The Museum of Norwich, Norfolk Museums Service

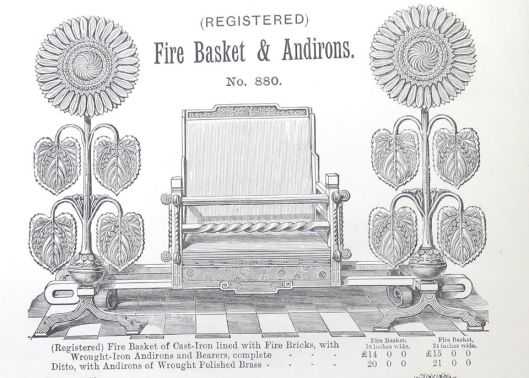

Jeckyll designed numerous pieces of metalwork for the fireside, including perhaps his best-known items: andirons or firedogs in the form of the sunflowers that were to become emblematic of The Aesthetic Movement [7,2]. These sunflowers fenced in Jeckyll’s Pagoda that once stood in Chapelfield Gardens and – in reproduction form – now decorate the gates to these Gardens and to Heigham Park (see previous post [2])

Barnard Bishop and Barnards catalogue 1884. (c) Museum of Norwich, Norfolk Museums Service

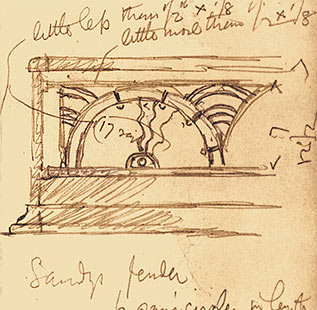

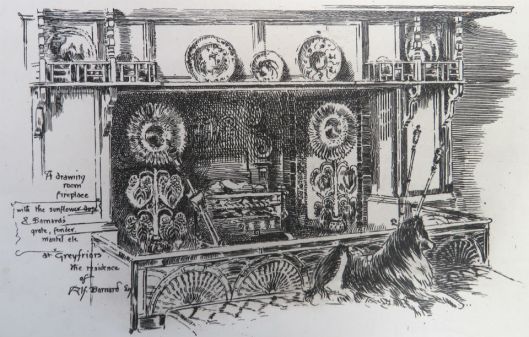

But it was this fender – seen in the apartment of Jeckyll’s friend, the Norfolk painter Frederick Sandys – that impressed a leading figure of the Anglo-Japanese Movement, E.W. Godwin. Indeed, Whistler insisted on having one of these fenders in his own apartment even though Godwin, who was refurbishing it, could have supplied fenders in his own designs [4].

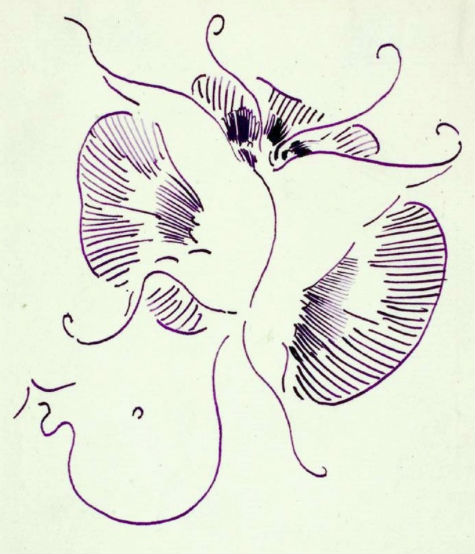

EW Godwin’s sketch of the ‘Sandys fender’ (c) Victorian and Albert Museum, London

This fender can be glimpsed in part of a larger sketch made in Charles Barnard’s home ‘Greyfriars’, Norwich (demolished). Jeckyll’s sunflower andirons are also illustrated.

Firedogs. (c) Museum of Norwich, Norfolk Museums Service

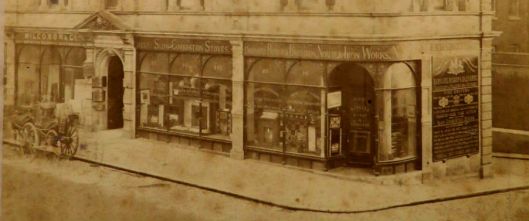

These were not prototypes made just for friends, for the fender must have been sold in fair numbers through Barnards’ catalogues and showrooms. Barnards’ Norwich showroom was on Gentleman’s Walk next to the market. By the 1930s the Hope Brothers had taken over the shop but it was still possible to see on the second floor the balcony railings that Jeckyll designed.

(c) Picture Norfolk. Norfolk Museums Service

Barnards also had a showroom in Queen Victoria Street, London.

Barnards London showroom (c) Museum of Norwich, Norfolk Museums Service

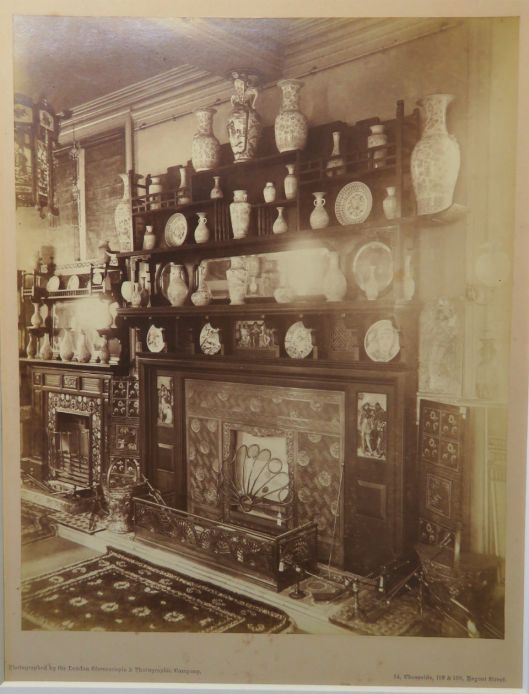

Below, we can see the fender advertised in the London showroom – the photograph providing a glimpse of the mishmash of Japanese, Chinese and even medieval influences available to the rising middle classes wanting to establish their Aesthetic credentials.

Barnard, Bishop and Barnards London showroom in the latter part of the C19. (c) Museum of Norwich, Norfolk Museums Service

The scalloped pattern, which became one of Jeckyll’s most frequently used motifs, was based on a Japanese design. For the fender, Jeckyll had used a single layer of semi-circles as the main motif but it is clear from his other work that this had been extracted from the larger seigaiha (blue ocean wave) design.

Seigaiha pattern on a kimono. (c) SmithjackJapan on Etsy

The overlapping waves were also used on cast-iron garden benches.

Barnards catalogue 1884. (c) Museum of Norwich, Norfolk Museums Service

A local application of the seigaiha design can be seen on the gates at Sprowston Manor Hotel on the outskirts of Norwich.

Jeckyll also used the wave design independently of the work he did with Barnards. Here it is seen in a terracotta plaque on the garden wall of High House, Thorpe St Andrew (left) and on a quadrant from the ceiling of the Boileau Memorial Fountain (right, demolished) that once stood at the junction of Newmarket and Ipswich Roads near the old Norfolk and Norwich Hospital (see previous post on the fountain [1]).

Left, Jeckyll plaque at High House, possibly made at the Costessey Brickworks. Right, a quadrant of the ceiling from the Boileau Fountain [1]

Fabric is not always durable but in this case the japonaise embroidery, made to Jeckyll’s designs, outlived the Chapelfield Pagoda that was dismantled in 1949. Fortunately, the hangings that decorated the pagoda at international exhibitions are conserved in Norwich Castle Study Centre –the seigaiha design bottom right.

Left: The Chapelfield Pagoda. Right: Jeckyll’s hangings used to decorate the structure when it was exhibited internationally. (c) Norfolk Museums Service

Jeckyll was an inventive designer who was certainly not restricted to one design or material. He had previously collaborated with the sculptor Sir J Edgar Boehm on the Boileau memorial Fountain and when Boehm sculpted the monument to Juliana, Countess of Leicester for the estate church at Holkham Hall it is highly likely that Jeckyll designed the japonaise base [4].

Base of the monument to Lady Leicester in the church of St Withburga, Holkham Estate, Norfolk, which is attributed to Thomas Jeckyll

Sources

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/04/15/thomas-jeckyll-the-boileau-family/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/01/06/jeckyll-and-the-sunflower-motif/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2015/12/26/two-bs-or-not-tw…s-thomas-jeckyll/

- Soros, Susan Weber and Arbuthnott, Catherine (2003). Thomas Jeckyll: Architect and Designer, 1827-1881. Yale University Press.

- Ives, Colta Feller (1974). The Great Wave: The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- The Cult of Beauty (2011). Eds Stephen Calloway and Lynn Feder Orr. V&A Publishing

- The Aesthetic Movement (1973). Ed, Charles Spencer. Academy Editions, London.

Thanks to: Hannah Henderson, Museum of Norwich, Bridewell Alley for showing me the Jeckyll collection; to Michael Innes for allowing me to photograph the Jeckyll terracotta at his house; to Mary Parker, warden of Ketteringham Church for providing the photograph of the ceiling in the Boileau Memorial; to Lisa Little of Norwich Castle Study Centre, Norfolk Museums & Archaeology Service, Shirehall,for showing me the Jeckyll hangings and to Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk for permissions.

Visit the display of Barnards’ work and Jeckyll’s designs in The Museum of Norwich, Bridewell Alley, Norwich

The Norwich Society helps people enjoy and appreciate the history and character of Norwich. Visit: www.thenorwichsociety.org.uk