The Society of United Friars was founded on the 18th of October 1785 in a Norwich ’house of public entertainment’. Conviviality was written into its constitution that rejected religion and politics in favour of ’social intercourse mellowed with wine and incensed with the fumes of tobacco.’ At their subsequent meetings the brothers would wear the habit of the particular monastic order to which they had been assigned and finger rosaries of 24 beads representing virtues. They also wore pink skull caps representing the tonsure [1,2].

Overseeing the mock medieval ceremonial was the Abbot who, like all other abbots, was named Paul. The first was 33-year-old Thomas Ransome, humorist, ’considerable wit’ and leading light of the fraternity [1, 2]. The tone is skittish but what prevented the United Friars from being written off as another drinking club was that for over 30 years its members met to discuss art, science, music, literature and raise money to feed the poor.

Little is known about the founder Thomas Ransome. In Peck’s Norwich Directory for 1802 he is simply listed as ‘Gent 14 Castle Meadow. Born abt 1752. Died 30 May 1815 aged 63. Wife Margaret Walker.’ We do know that Ransome was a clerk who worked in Gurney’s Bank on Redwell (now Bank) Plain and was ‘noted for the beauty of his penmanship’ [3]. As a ‘Franciscan’ he was said to be devoted to the fine arts and the sciences of optic and mechanics. The seven other founding members, described as ’men of more than ordinary education and attainment’, shared the minor offices of prior, procurator, bursar, almoner, hospitaler, camerarius (or chamberlain), cellarer etc [2, 3].

Initially, meetings were held on Thursdays and Sundays [2] in unsatisfactory rooms provided by Brother Wilkins in St Martin at Palace. These were replaced by rooms in ‘White Horse Yard’, possibly in Magdalen Street – although there were several yards of that name [4]. In 1791 these, too, were abandoned in favour of a house that member Henry Dobson, builder, had bought near St Andrew’s Hall. But, needing to reduce expenses in favour of their charitable work, the Friars moved in 1799 to rooms in Crown Court, Elm Hill, with broad mullioned windows and a high, ornately plastered ceiling. The building originally on this site was the town house of the letter-writing Paston family [5] but, like most of Elm Hill, it was destroyed by the fire of 1507. Rebuilt by mayor Augustine Steward as a quadrangle house the front (numbers 22-26) survives as the Strangers Club but the buildings behind, which accommodated 155 people, were demolished as part of the 1927 slum clearance [4].

We can piece together a description of the meetings: the brothers sat around a horseshoe of long tables covered in scarlet cloth, formed around the fireplace [1,2]. Nine tall wooden, medieval candlesticks were placed on the table, illuminating 12 Gothic chairs with the Abbot and Prior sitting on raised seats. Members discussed scientific, literary, social and philosophical subjects. William Beechey, for example, presented a ‘short paper on the history of sculpture since antiquity’ (how could that have been ‘short’?). Provided they dressed as pilgrims, outsiders invited by a member could attend the discussions but not the conclave [2]. Several paintings hung on the walls; the one that hung behind the Abbot’s chair was of St James of Compostela donated by honorary member John Sell Cotman in lieu of the initiation rite of reading a paper on the religious order to which he’d been assigned [1]. The saint points to one of the Friars’ bywords, Charity. (Sobriety is at the bottom of the list). The attributes listed on Cotman’s painting are probably related to the beads on the Friars’ rosaries; one Brother who was late in making his contribution was threatened with loss of a bead, probably representing Punctuality [1].

Over a low ornamental cupboard was a large case which contained an orrery, magnifying glasses, fossils, an amphora, a splinter of a cannon used in Kett’s Rebellion, a piece of a mummy, fragments of sculpture from Norwich Cathedral, a hortus siccus [a collection of dried plants], an electro machine, a silver grace cup. air pump, microscope &c.

From the JJ Colman Collection, at the Norfolk Record Office, of papers relating to the United Friars [1].

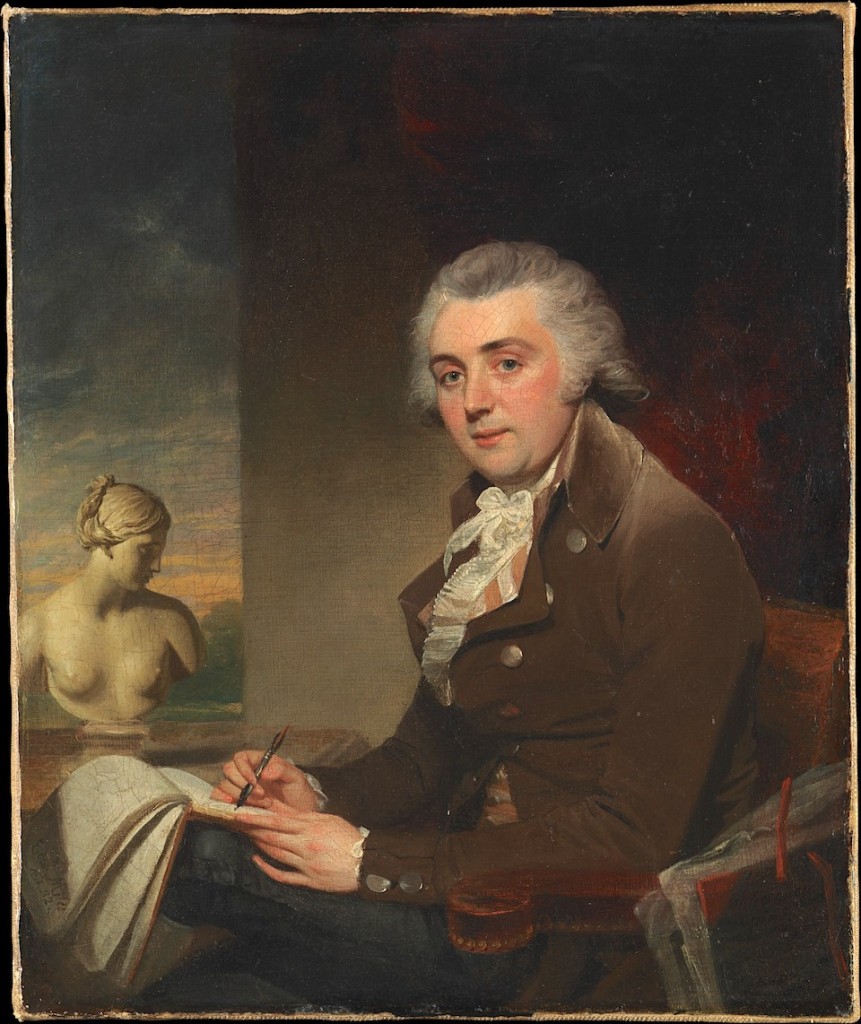

The painting over the mantelpiece was The Tomb of Ceolwulph by one of the founding members, William Beechey.

Beechey was represented by other paintings including one of the Reverend John Walker, a poet and Dissenting minister [6]. Beechey came to Norwich about 1782 and lived at 4 Marketplace for five years[7]. During his time in the city he ‘tapped a considerable latent demand for good portraiture’ [7]. In 1785, eight of his nine works shown at the Royal Academy were of Norwich or Yarmouth clients. His civic portrait of the mayor, Robert Partridge, is dated 1784. Back in London Beechey became a pupil of the eminent society painter Johan Zoffany and, as Sir William Beechey, he himself became a portraitist to the fashionable. In 1801 the City of Norwich paid him £210 to produce a life-size painting of Lord Nelson in recognition of his Norfolk origins. It hangs in St Andrew’s Hall.

After the sittings Nelson gave Beechey his bicorn hat.

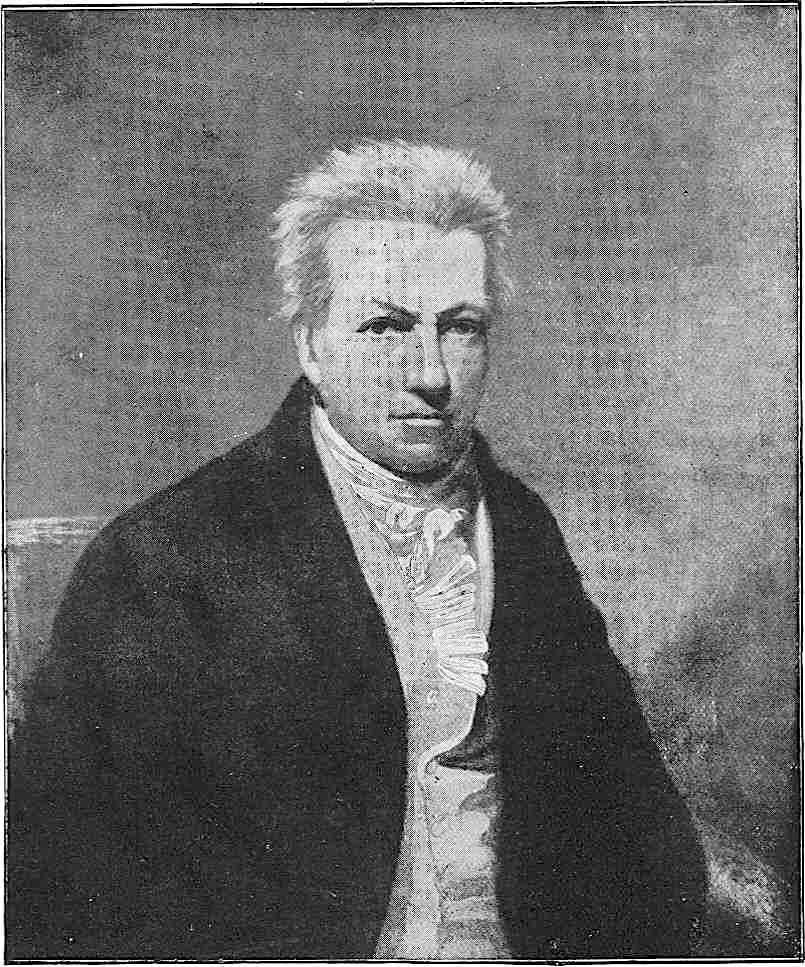

Another of the founding members was Edward Miles (1752-1828), ‘a Yarmouth man’ and painter of miniatures. Like his contemporary and friend Beechey he had studied at the Royal Academy under Sir Joshua Reynolds. In Norwich, Miles lived three doors away from Beechey at number 7 Marketplace [7]. In 1794, as miniaturist to Queen Charlotte, Miles established himself in Berkeley Square where he gained much aristocratic patronage. In 1797 he extended his fortune by moving to St Petersburg to serve Czar Paul 1 and then his son Alexander 1. In 1807 he moved to Philadelphia where he died in 1828 [8].

Another of Ransome’s disciples present when the fraternity was founded was Mostyn John Armstrong (d.1791), Norfolk historian, county surveyor and topographer. Armstrong lived near Gurney’s Bank at 2 Redwell Street and became a lieutenant in the Norfolk Militia. He and his father had made surveys in the north of the kingdom but after moving to Norfolk they failed to complete an advertised one-inch map of the county and William Faden may have imported some of the Armstrongs’ work for the first large-scale map of the county. Although it carried no author’s name, it is believed that a ten-volume ‘History and Antiquities of the County of Norfolk: Norwich’ was masterminded by Mostyn. Certainly, his name appears on several illustrations including a Plan of Norwich [9]. Brother Armstrong’s name also appears in minutes of the Friar’s meetings as the man who supplied a ‘leg of pork with forcemeat’ for the evening meal, which would have been eaten upstairs in the refectory. Armstrong suffered the mild humiliation of having his contribution described as being ‘very nice (but) not quite enough for supper’ [2]. Perhaps more than the usual 10 or 12 Friars [3] turned up that evening?

William Wilkins (1751-1815), antiquary, architect and lessee of the Norwich theatre [3], is described as overcoming ‘the disadvantages of a meagre education’, presumably to distinguish him from his Cambridge-educated son, William Wilkins Jr (1778-1839), who drew up the plans for Trafalgar Square. The father’s name crops up in connection with ‘the Architect of Georgian Norwich’, Thomas Ivory, for whom he was contracted as a ‘plaisterer’ [10]. In a war of words over the contract to redesign the Norwich Castle Keep (1789-1793) the winner, Sir John Soane, called Wilkins a ‘stuccatore (plasterer) … fancying himself as an architect’. In 1820, Wilkins Jr was to restore family honour with his own successful design for a modified panopticon [10,11].

Wilkins Senior served his one-year term as Abbot [2]. Locally he was known for managing the Norwich Theatre, which he restored around 1800 at a cost of £1000. When he died his son was left, in addition to the Norwich Theatre Royal, controlling interest in theatres in Yarmouth, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich, Colchester and Cambridge. In 1819, Wilkins Junior was to re-design the Theatre Royal St Edmunds in a Greek Revival style [11].

Of the original eight founders, Ransome, Beechey, Miles, Armstrong and Wilkins all left a trace but biographical details are scant for the remaining three: Rishton Woodcocke is listed in Chase’s 1783 Norwich Directory as Attorney at Law of 5 White Lion Street; Thomas Holl seems to have been member of the family of boot and shoe makers in the city centre; and searches for plain John Cook yield uncertain results. Could he be John Cook Senior, Beadle and an Agent for the Sun Fire Office, or his son John Cook Junior who owned a glass warehouse, or – much more likely – the country gentleman painted by Brother Sir William Beechey?

By the time the United Friars came together, Norwich was no longer the most populous provincial city, pushed into ninth place by the rise of the northern manufacturing centres. Slow to abandon the hand loom, the Norwich textile industry entered a long decline. Despite this eclipse, the latter part of the eighteenth century was a gilded era for a city that was still the capital of a prosperous agricultural region where banking and insurance flourished and a wealthy elite came for entertainment, improvement, social interaction and shopping. Liberated from the religious extremism that regulated life in the 1600s, citizens of the long Georgian century (1714-1830) enjoyed greater freedom to explore ideas in a rational way. Norwich had the first truly provincial paper (the Norwich Post) and by the end of the Georgian era could claim three of the country’s six provincial papers. By the end of the eighteenth century the city’s literary reputation – to which female writers made a major contribution – earned it the title of ‘The Athens of England’ [6]. And the Norwich Society of Artists, founded in 1803, was the first provincial school of painting; like their Dutch neighbours, its members felt no need to people their paintings with religious or classical figures.

This is the rich cultural background out of which the Society of United Friars emerged. Sampling the general membership provides an intriguing slice through progressive provincial society.

William Taylor, son of a wealthy Norwich textile manufacturer and translator of German Romantic literature, was part of the city’s radical intelligentsia; he had a national reputation and was ‘the centre of the literary circle in the city’ [3]. A Dissenter, he worshipped at the Octagon Chapel where Amelia Opie (née Alderson) attended until she became a Quaker after her father’s death. In 1794-5 Taylor and Anne Plumptre – who accompanied Amelia Opie to France to see the revolution for themselves – established a short-lived literary and political magazine named ‘The Cabinet, by a Society of Gentleman’. This was produced by the man who published ‘The Rights of Man’ by Thomas Paine [12, 13]. Opie contributed 15 poems to its first three issues before the journal was gagged as part of the government’s clamp-down on revolutionary sentiment.

John Clayton Hindes appears in Chase’s Directory (1783) as, ‘Hatter and Hosier No 12 Back of the Inns’, just off the Marketplace. From its reopening in 1801, until 1817 Hindes, Manager of the Norwich Company of Comedians (actors), was manager of the Theatre Royal that had been remodelled by William Wilkins. He died in 1824 aged 71 in his house in nearby Chapelfield.

Thomas Martineau. The Martineau family of Huguenot descent had two Thomases. Thomas Sr (1764-1826) was a manufacturer and merchant of textiles who, from 1797, served as deacon of the Octagon Chapel in Colegate – perhaps the intellectual centre of the city’s Dissent. His eldest son (1795-1824), Thomas Jr, was a surgeon who co-founded the Norfolk and Norwich Infirmary for Diseases of the Eye on St Benedicts’ Plain. He died on his return from Madeira, aged 29 [14].

Bartlett Gurney was a member of the Gurney banking family who bought their premises from a wine merchant on Redwell Plain. On the death of his father, Bartlett (1756-1802) took over the bank and for a while lived next door [2]. Bartlett Gurney was a Whig and in his book on Norwich, a ‘Jacobin City’ [3], CB Jewson described the Gurney bankers as being ‘radicals and dissenters’ at a time when revolution was in the air. The United Friars contained Whigs as well as Tories and, in a city renowned for its violent politics, it was wise for them to largely abstain from political debate.

Bartlett Gurney, one-time Abbot, presented the Friars with a pump and a portable chest of chemicals. Their interest in this area was demonstrated in 1786 when they invited Adam Walker – who was in the city to deliver a series of lectures on general science – to give the Brothers two special lectures on chemistry [15]. The eighteenth century fascination with the emergent sciences has been attributed [15] to the climate of dissent in which individuals felt free to investigate ideas according to their conscience rather than accept dogma. Norwich was a famously dissenting city and as early as 1676 a census of the Norwich diocese revealed about one third Non-conformists [6]. One hundred years later, given the Friars’ no-religion charter, it seems hardly surprising that scientific experimentation should feature so heavily on their agenda.

Hudson Gurney (1775-1864) inherited considerable wealth from the Gurney banking side and from the Barclay Perkins brewery, one of the largest in London. In 1811 this allowed him to rebuild Keswick Hall, on the outskirts of Norwich, in Regency style; in London he lived in St James Square. He devoted time and money to Anglo-Saxon studies and was elected Fellow of both the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries. His early ambition to enter politics was achieved when he stood as proxy to Bartlett Gurney in the Norwich election of 1796 but he hated the turbulence of the city’s politics (see post on Revolutionary Norwich [16]). Instead he sat five times ‘without the anxiety of elections’ [17] for Newtown Isle of Wight. The reputation he gained as a revolutionary Jacobin was later dismissed as a youthful aberration for as an MP he sat on the neutral benches; he even shunned his Quaker upbringing and never became a Friend. In his own estimation he ‘did nothing and thought much.’ He is buried in Intwood church where the Unthanks lie.

William Stevenson (1741-1821) was best known for his 35-year-long ownership of The Norfolk Chronicle, one of only a handful of provincial newspapers. He was also proprietor of the printers Stevenson, Matchett and Stevenson in the marketplace. He, too, was a miniaturist, having studied, and exhibited, at the Royal Academy under Sir Joshua Reynolds. On coming to Norwich he taught drawing. Sheriff in 1799, Stevenson died in his house in Surrey Street and is commemorated by a wall monument in St Stephen’s church [18].

Luke Hansard (1752-1828), born in Norwich, became compositor to a London printer who published the Journals of the House of Common [19,20]. In 1774 he became partner for the rest of his life and his membership of the United Friars, back in Norwich, was on an honorary basis [3].

Hansard’s eldest son Thomas added the name ‘Hansard’ to the cover and this became the name by which official parliamentary reports were known.

Based at his commercial nursery in Catton, a village three miles north of the city, George Lindley was an expert plantsman specialising in the science of fruit growing (pomology). Several Norfolk apples, such as Baxter’s Pearmain, were either sold first or rediscovered by Lindley [21]. Despite his expertise the business was not profitable and his relative poverty would explain his honorary membership [22]. George did, however, find the means for his son John to be educated at Norwich School. John became Professor of Botany at University College London where he taught Botany in its own right and not as an adjunct to Medicine. His name is commemorated in the largest collection of horticultural books in the world – the Royal Horticultural Society’s Lindley Library [23].

George Lindley’s name occurs frequently in the minutes of the society: he presented a scheme for planting an orchard [24], read a paper ‘On the Generation of Mushrooms’ [25] and another ‘On the Nature and Properties of the Swedish Turnip’ [26]. After Brother Thomas Suffield donated a microscope [3] Lindley made a formal request in June 1797 to borrow it and was allowed to use the microscope for a fortnight [27]. Lindley’s investigations were only part of a wider interest that the brotherhood took in the sciences, encompassing gravity, navigation, the solar eclipse, even conducting experiments at Brother Gurney’s at Wroxham on saving lives at sea [3]. We know of their collection of scientific instruments that Friar Blyth Hancock – a poorly-paid schoolmaster and prolific presenter of papers on the physical sciences – was paid half a crown a week to look after. There is an illustration of an electrical device in the United Friars papers in the Norfolk Record Office [1].

Edward Colman was Assistant Surgeon at the Bethel Hospital from 1790 until his death in 1812. He was Sheriff in 1795 and Abbot of the Friars in 1799. At a meeting he told a story of young John Crome when he lived as errand boy with Dr Edward Rigby, art collector, radical and a surgeon famed for conducting operations on the Norfolk affliction of ‘the stone’ [3]. One night, some of the doctor’s students placed a skeleton in the bed of the boy who would go on to be co-founder of the Norwich Society of Artists [28]. Incensed, Crome flung the skeleton down the stairs.

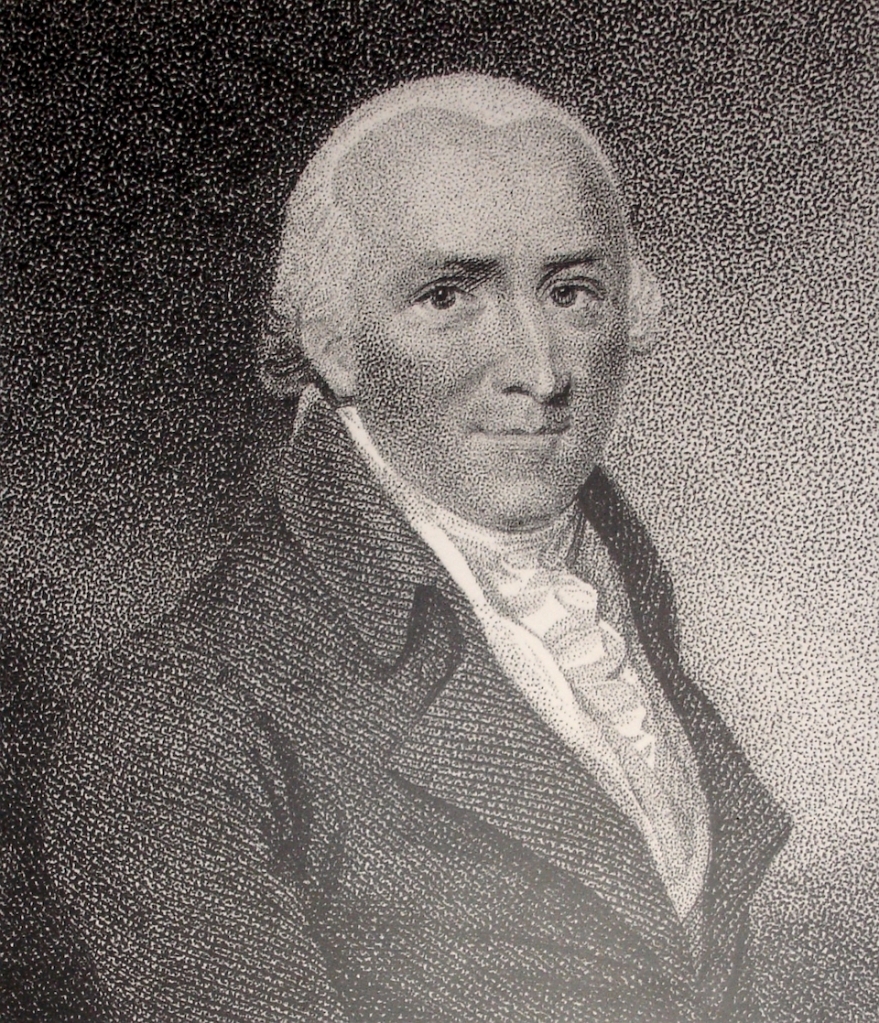

The meetings of the United Friars were just a few dozen steps from Elisha de Hague‘s office at No 5 Elm Hill where he worked with his father of the same name. Beechey painted his brother Friar but I find this portrait by Gray to be more characterful.

A descendant of Protestant ‘Strangers’ who fled The Netherlands in the sixteenth century, de Hague Jr (1755-1826) became councillor, Land Tax Commissioner and – like his father – Town Clerk. He was a founding member of the Norfolk and Norwich Association for the Blind and in 1823 was involved with an Act of Parliament to introduce gas lighting to Norwich [28]. At his initiation into the Friars he presented an essay on ‘The History of the Order of the Crouched (aka Crutched or Crossed) Friars and an account of their Houses in England’ [1]. For this he wore their sky blue habit [1]. de Hague met Parson Woodforde whose descriptions of jaunts to the city bring Georgian Norwich to life [30, 31]. But on the 24th of September 1792 the parson was too ill (probably with gout) to travel into the attorney’s office in Elm Hill. Instead, ‘Mr de Hague from Norwich waited on me this morning with parchment deeds to sign’ [31].

The landscape designer Humphry Repton (1752-1818), a ‘Carthusian’, was also offered honorary membership as an out-of-towner [32].

Repton was born in Bury St Edmunds but had close ties with Norfolk; he was educated at Norwich Grammar School and is buried in the market town of Aylsham. In the famous Red Books he gave to clients, Repton presented designs with movable flaps that illustrated the project ‘before and after’. His first two projects were for Norwich mayor and textile merchant Jeremiah Ives at Catton Park, just north of the city, and for Thomas Coke of Holkham Hall. Perhaps his finest achievement in Norfolk is his design for Sheringham Park.

Charles Jewson [3] records that one of the distinguished out-of-towners to receive honorary membership was ‘the eccentric Earl of Orford’. This would have been Horatio (Horace) Walpole (1717-1797) Fourth Earl of Orford who, like Repton, joined the Friars as a ‘Carthusian’. Horace, the youngest son of the first British Prime Minister, the Whig Robert Walpole, was a writer, antiquarian, collector, dilettante. He is best remembered for designing his house Strawberry Hill, Twickenham, as an early example of the Gothic Revival style that would dominate Victorian public building. Both he and his father are buried in St Martin’s church on the Houghton Hall estate, Norfolk.

Of Huguenot descent, Thomas Amyot (1775-1850) the antiquary was son of Peter Amyot the clockmaker who was visited in his shop in the Haymarket by Parson Woodforde [31]. To prepare him for life as a country attorney Thomas was articled for one year to the ‘radical’ [3] lawyers Foster and Unthank – this being the William Unthank who bought the land in Heigham on which the Victorian terraced housing around Unthank Road was built [33]. In the 1802 election Amyot was agent for the standing MP for Norwich, William Windham of Felbrigg Hall [34]; in 1806 Amyot gave up his legal practice and joined Windham in London as his private secretary. Through Windham’s influence Thomas gained the lucrative appointments that gave him the freedom to pursue his archaeological studies for which he was conferred fellowships by the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries [34].

CHARITY In October 1793 Brothers Walker and Wilkins proposed that something be done to relieve the poor who were suffering from the cold weather, lack of employment and the rise in prices. In August 1795 the price of wheat had been 80 shillings per quarter but by December 1800 it had risen to 150 shillings due to the war with revolutionary France [2, 35]. In response the Norwich poor attacked bakers’ shops and refused to disperse until the Riot Act was read.

The United Friars’ response over this period was to distribute food to the poor who assembled at their gate. The Friars raised money by selling tickets to members and non-members and this allowed them to provide a penny loaf and two pints of soup per person on five evenings a week. From April 1796 to April 1807 the Friars spent nearly £200,000 (at today’s prices) on soup and bread [34]. Brothers Bartlett Gurney and Elisha de Hague were appointed to make certain that the soup was of good quality. Brother Taylor performed experiments to demonstrate that superior soup could be made more cheaply than they were being charged and may have been the impetus behind the Friars’ sponsorship of the Norwich Soup Society.

On the fifth of February 1828 the Society of the United Friars convened its last recorded meeting when only three Brothers were present. The last surviving Brother was James Bennett who had been in business with horologist and fellow Friar, Peter Amyot. Bennett died on January 18th 1845 and is remembered as the first man to have made an electrical machine in Norwich [36].

Sources

- From JJ Colman’s collection of United Friars papers, Norfolk Record Office COL/9/193/1-7

- E.A. Kent (1902). Some Notes on the Society of the United Friars. From, Norwich Science Gossip Club Annual Report, 1902. Norfolk Heritage Centre NO62.

- C.B. Jewson (1975). The Jacobin City: A Portrait of Norwich in its Reaction to the French Revolution 1778-1802. Pub: Blackie & Son, Glasgow and London.

- Frances and Michael Holmes (2015). The Old Courts and Yards of Norwich. Pub: Norwich Heritage Projects.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/12/15/the-pastons-in-norwich/

- David Chandler (2010). “The Athens of England”: Norwich as a Literary Center in the Late Eighteenth Century. In, Eighteenth Century Studies 43(2) pp 171-192.

- Trevor Fawcett (1978). Eighteenth Century Art in Norwich. In, The Volume of the Walpole Society (1976-8) 46, pp 71-90.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Miles_(painter)

- Raymond Frostick (2002). The Printed Plans of Norwich 1558-1840: A Carto-Bibliography. Pub: Raymond Frostick, Norwich.

- Stanley J Wearing (1926). Georgian Norwich: Its Builders. Pub: Jarrold & Sons Ltd, Norwich.

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (2002). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1: Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- Penelope Corfield (2004). From Second City to Regional Capital. In, ‘Norwich since 1550’ pp 139-166. Eds Carole Rawcliffe and Richard Wilson. Pub: Hambledon and London.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Taylor_(man_of_letters)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martineau_family

- Trevor Fawcett (1972). Popular Science in Eighteenth-century Norwich. In, History Today vol 22, pp 590-595

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2021/03/15/revolutionary-norwich/

- https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/gurney-hudson-1775-1864

- https://suffolkartists.co.uk/index.cgi?choice=painter&pid=3415

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luke_Hansard

- https://www.stationers.org/news/features/paintings-in-stationers-hall-the-portrait-of-luke-hansard-by-samuel-lane

- http://www.englandinparticular.info/orchards/o-norfolk-f.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Lindley

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/04/15/the-norfolk-botanical-network/

- Norfolk Record Office COL9/96

- Norfolk Record Office COL9/94

- Norfolk Record Office COL/9/193/1

- Norfolk Record Office COL9/2

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/09/15/the-norwich-school-of-painters/

- https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private-lives/taxation/case-study/norwichconnection/elisa-de-hague/elisha-de-hague-about-/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2020/11/15/parson-woodforde-goes-to-market/

- James Woodforde (1924). The Diary of a Country Parson, 1758-1802. Pub: Oxford University Press.

- Humphry Repton in Norfolk.(2018). Eds Sally Bate, Rachel Savage and Tom Williamson. Pub: Norfolk Gardens Trust.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/04/15/colonel-unthank-rides-again/

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Amyot,_Thomas

- Norfolk Record Office NRO COL/9/193/4

- Norfolk Chronicle January 18th 1845.

Thanks

I am grateful to Alan Theobald and to Martin Brayne of the Parson Woodforde Society for their assistance. Clare Everett of Picture Norfolk is thanked for permissions.