Martin Battersby wrote that the sunflower has no special association with Japanese art (1) yet, during the second half of the nineteenth century, it became the symbol of the Anglo-Japanese Aesthetic Movement.

Norfolk’s Thomas Jeckyll played a part in its popularization – his Japonaise designs for fireplaces, produced by the Norwich foundry of Barnard Bishop and Barnards, helped connect the sunflower motif with other more recognisably Japanese emblems like cherry blossom, fan shapes and cranes. The sunflower crops up on illustrations, paintings, metalwork, china. One explanation for its popularity was “… the ease with which its simple flat shape could be wrought into a formal pattern…” (1).

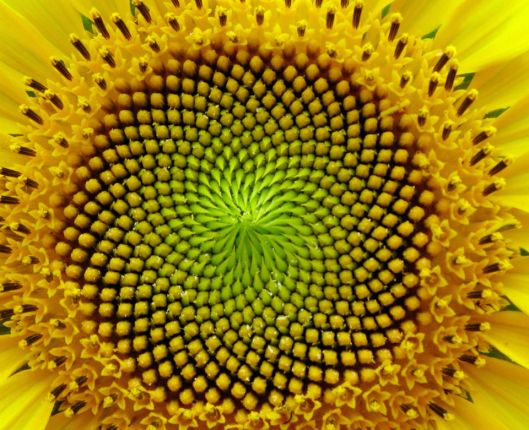

Clockwise and anti-clockwise spirals

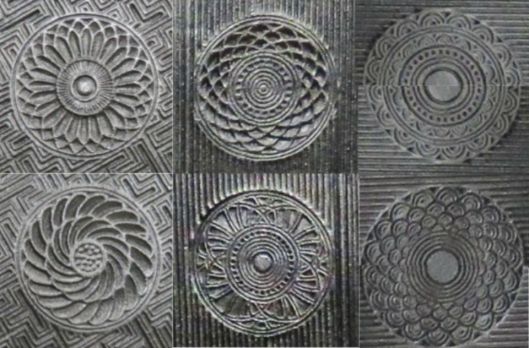

It may be beautiful but the sunflower’s flat shape is anything but simple. The pattern of seeds on the flower head is mathematically complex, comprised of clockwise and anti-clockwise spirals. The numbers of right-handed and left-handed spirals, which change as the flower grows, are adjacent numbers in the Fibonacci series; for example 55 and 89, or 8 and 13. Described by Leonardo Fibonacci in the thirteenth century, this series is 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21 etc, where the next number is the sum of the previous two. Jeckyll, like all other artists (such as van Gogh in his later series of sunflower paintings [1888]) had to devise a shorthand for representing such complexity. Fortunately, in working for Barnards, Jeckyll was able to exploit their fine casting in his experiments to translate the Fibonacci series into a visually pleasing effect.

Abstracted flower designs in which the contrary spirals of the sunflower are represented with varying degrees of success. On a single cast-iron fireplace Jeckyll used six different sunflower designs (the two motifs at right were semicircles that I mirror-imaged to form whole circles). A Barnards fireplace at Norfolk Museums Service, Gressenhall.

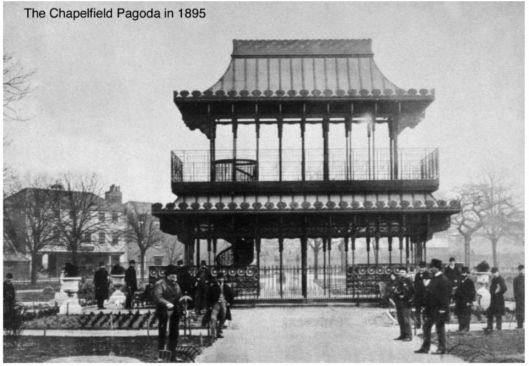

Jeckyll was certainly not the only one to use the sunflower motif in an Arts and Crafts context – William Morris had popularised it a generation earlier – but as a member of a London-based circle of connoisseurs of oriental art he was one of the first to apply it within the Anglo-Japanese Aesthetic Movement. One of his most famous designs was for Barnard Bishop and Barnards’ cast-iron Pavilion or Pagoda for the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, 1876. Seventy two sunflowers, three-foot-six inches high, formed the railings around the Pagoda (2).

Jeckyll’s Pagoda exhibited in Philadelphia, surrounded by the golden sunflower railings (Courtesy Jonathan Plunkett [3])

The sunflower railings can just be seen at the base of the Pagoda installed in Chapelfield Gardens, Norwich. (Courtesy http://www.racns.co.uk [4])

When exhibited, the ceilings and upper parts of the walls of the Pagoda were decorated with embroidered textiles in the Japanese style. But when the pagoda was dismantled some 70 years later these seem to have been cut for curtains; fortunately large fragments are conserved in the Costume and Textile Department at Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery (5).

For the Pagoda, Jeckyll designed textile hangings embroidered with cranes and Japanese flowers (1876). (Accession number, NWHCM: 1968.240)

Below, an early colour photograph from the essential George Plunkett photographic archive of Norwich (3) shows the Pagoda in 1935, left of the bandstand.

![Chapel Field bandstand and pagoda COLOUR [0738] 1935-08-21.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/chapel-field-bandstand-and-pagoda-colour-0738-1935-08-21.jpg?w=529)

The Chinese Pagoda (left) in 1935, apparently painted Corporation Green.(Courtesy of georgeplunkett.co.uk)

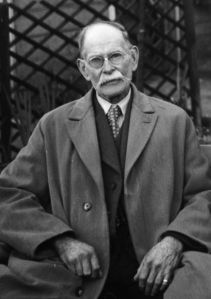

The photographer George Plunkett’s great-uncle, the wonderfully named Aquila Eke, was a son of a blacksmith. He also became a blacksmith at Barnard Bishop and Barnards’ Norfolk Iron Works and is said to have made much of the bas-relief work for the Pagoda (3).

Aquila Eke 1937.(Courtesy Jonathan Plunkett)

“At about the age of 10 [Aquila] ran away from home, finding his way to Norwich. (On arrival, he thought he had reached London!). He found his way into the blacksmith’s shop in the yard of the Royal Oak public house in St Augustine’s Street, where he was recognised, and promptly driven back to Drayton. However, he eventually came to Norwich to work, and joined the Norfolk Ironworks of Messrs Barnard, Bishop and Barnard, where [twelve years after running away] he assisted in the manufacture of the handsome wrought-iron pavilion which for so many years graced Chapel Field Gardens.”(From the Plunkett family archive, courtesy of Jonathan Plunkett).

In 1942 the Pagoda was damaged during the ‘Baedeker’ raids that bombed cities judged by the German travel guide to be of cultural and historic importance. Blast damage and general corrosion led to the dismantling of the structure in 1949. Some panels of the sunflower railings were salvaged and, after being used at the tennis courts of Heigham Park, Norwich, were refurbished in 2004 as the park’s entrance gates. During restoration, Sarah Cocke (4) remembers a mixture of old and new sunflowers mixed in cardboard boxes at Norwich City Works. Presumably, Sarah’s photograph below shows a new sunflower since it has a simplified single row of petals instead of a double row as in the original pieces.

A ‘Heigham Park’ sunflower during restoration. Note that the highly complex double spirals are now reduced to one. (Courtesy Sarah Cocke)

This was the same design that Jeckyll used for the andirons in the fireplace of the Peacock Room, one of Jeckyll’s few remaining vestiges after Whistler’s makeover (see previous post).

Jeckyll’s sunflower andirons and grate – some of his few untouched contributions to the Peacock Room. (Courtesy Freer and Sackler Galleries, Washington, USA [6])

Whistler’s painting above, Jeckyll’s sunflowers below (Freer and Sackler Galleries [6])

The most recent manifestation of Jeckyll’s sunflower design is in the newly-made gates to Chapelfield Gardens, where the originals had surrounded the Pagoda over 125 years ago.

Twenty-first century sunflower gates at the entrance to Chapelfield Gardens, Norwich

The flower motif is ubiquitous and can be found elsewhere in Norwich. The flatiron-shaped red brick and terracotta building (1880) at the junction of London and Castle streets was part of Edward Boardman’s London Street Improvement Scheme. On this building, around the top of the second storey, Boardman added a series of white terracotta roundels containing flowers with blue-glazed petals. Admittedly, these flowers are more daisy-like than sunflowers but so were some of Jeckyll’s own variations as he worked out ways of representing the sunflower – see, for example, one of his fireplaces in the third figure from top. Boardman would have been well aware of Jeckyll’s work for Barnards, whose showroom was just around the corner in Gentleman’s Walk.

Blue-glazed roundels.

At some point, perhaps for ease of manufacture in materials incapable of showing such fine detail as iron, what might once have been an Aesthetic sunflower becomes a generic daisy. The house at number 19 Ipswich Road is profusely decorated with diapered panels of Aesthetic-influenced flowers above windows and on a gable.

Repeated Aesthetic flower motifs in Ipswich Road, Norwich

At 50 All Saints Green is a restored (2015) former coach house and stables. It is highly decorative with two panels of terracotta flowers; one in the east end’s Dutch gable…

… and the other above the front door (below).

Although described as sunflowers the central apple-like structure sidesteps the complexity of Fibonacci spirals that Jeckyll had managed to convey in iron.

Jeckyll sunflower, ‘new’ gates at Chapelfield Gardens, Norwich

Sources

1. Martin Battersby (1973). Essay on ‘Aesthetic Design’. pp 18-24 In, The Aesthetic Movement, Ed Charles Spencer. Academy Editions .

2. Susan Weber Soros and Catherine Arbuthnott (2003). Thomas Jeckyll, Architect and Designer, 1827-1881. The Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture, New York. Pub, Yale University Press.

3. George Plunkett’s Photographs of Old Norwich http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Website/

4. Recording Archive for Public Sculpture in Norfolk and Suffolk. http://www.racns.co.uk

5. The Costume and Textile Department at the Castle Study Centre, Norfolk Museums Service. http://www.museums.norfolk.gov.uk/Visit_Us/Norwich_Castle_Study_Centre/index.htm

6. The Freer and Sackler Galleries, The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art. Washington D.C., USA. http://www.asia.si.edu/exhibitions/current/peacockRoom/pano.asp

Thanks to Sarah Cocke of racns; Jonathan Plunkett of the Plunkett photographic site; Lisa Little, Samantha Johns and Shaz Hussain of the Norfolk Museums Service.

Great post – thanks for bringing the hidden gems of Norwich’s decorative architecture to light. I’ll be paying more attention next time I’m strolling around town!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved this. Thanks for bringing the hidden gems of Norwich’s decorative architecture to light. I’ll be paying more attention next time I’m in town!

LikeLike

Your enthusiasm I’d infectious . I now have renewed interest in the Aesthetic Movement and the incorporation of the sunflower motif into domestic architecture

Pam Matthews

LikeLike

Reggie, have a look at Drew Pritchard’s website. He seems to have an interest in B,B and B too. http://www.drewpritchard.co.uk/products/thomas-jeckyll-tiled-insert

LikeLike

Yes, Drew Pritchard has wonderful stuff. That fireplace in the link is one of two in storage at Gressenhall Museum. Coincidentally, someone else sent me a photo after reading a Jeckyll blog to show she has the second Gressenhall fireplace in her bedroom (the one with six different sunflower motifs. So envious.

LikeLike

This “blog” (the first I have ever read) is most interesting. We learnt much about the pavilion and other sun-flower motifs in the Ipswich Road, etc.

Clearly, the sun-flower made a good decorative design but it also stood for striving, ambition, desire because the flower always turned towards the sun. I suppose that is why Jekyll used them in his fire-dogs. In a highly finished drawing of 1858, now in the Fitzwilliam, Rossetti has Mary Magdalene leaving a festive procession to join Christ who sits between pots of lilies and sunflowers. I think that Blake may say something about the sunflower and Rossetti was a great admirer of Blake. Morris writes about “sad, sick sun-flowers” in his poem “A good knight in prison”, published in his Defence of Guenevere” in 1858. Leighton, at the end of his life, c. 1894, painted “Clytie” who was turned into a sun-flower by Apollo after he abandoned her. The picture is illustrated in Ormond’s book on Leighton. Leighton’s friend G.F. Watts also did a bust-length sculpture of her turning towards the sun.

LikeLike

Thank you Alastair for those interesting comments about predecessors to Jeckyll’s sunflowers.

LikeLike

Pingback: Jeckyll and the Japanese wave | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Barnard Bishop and Barnards | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Sunflowers in the Peacock Room – Freer|Sackler

Pingback: The Captain’s Parks | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Chapel in the Fields | COLONEL UNTHANK'S NORWICH

Pingback: Japan goes on show | The Gardens Trust