I recently came across that quotation by Dorothy Parker about members of the Bloomsbury Group living in squares, painting in circles and loving in triangles. They couldn’t have done that in Norwich for although we have circles and triangles we don’t have squares. Instead, we have plains, an import from the Low Countries.

Plains aren’t restricted to Norwich for you’ll stumble across them in Norfolk and Suffolk; I came across this one in Great Yarmouth.

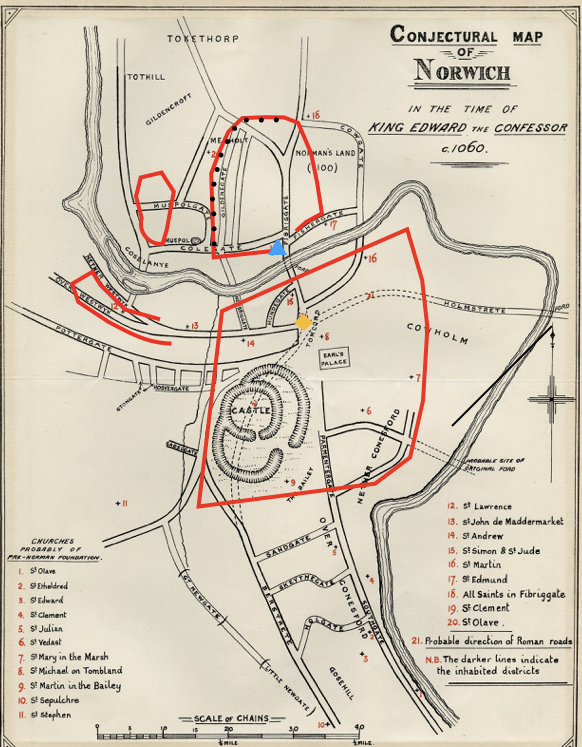

It was in 1566 that the Fourth Duke of Norfolk requested Queen Elizabeth’s permission to invite ‘thirty Douchemen’ to help revive Norwich’s flagging textile trade. The following year this trickle became a flood when Protestants from the Spanish Netherlands escaped the religious intolerance of Philip II of Spain [1]. But the word ‘plain’ for an open space predated these arrivals: Nicholas Sotherton’s eye-witness account of Kett’s 1549 rebellion refers to ‘the playne before the pallace gate’ [2] so the word was an earlier introduction, part of the city’s already long association with the Low Countries.

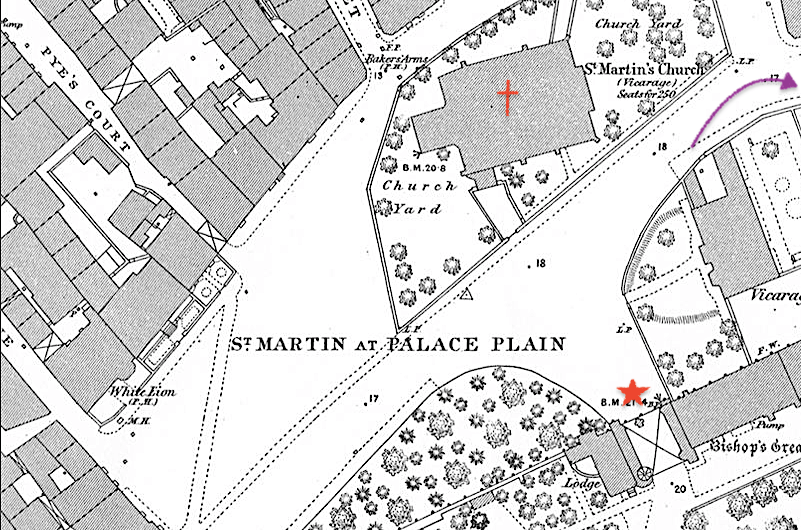

St Martin at Palace Plain – now the site of the Wig & Pen pub and John Sell Cotman’s house – was the site of a pitched battle between the King’s forces and Robert Kett’s men.

Lord Sheffield fell from his horse and, as was the custom, he removed his helmet expecting to be ransomed. Instead, he was bludgeoned to death by a butcher named Fulke. Sheffield and 35 others were buried in the adjacent church.

In his book The Plains of Norwich, Richard Lane wrote that only five of the fifteen Norwich plains are officially marked by a street sign; St Martin’s at Palace Plain is one of them as is Agricultural Hall Plain, at the east end of Castle Meadow [4].

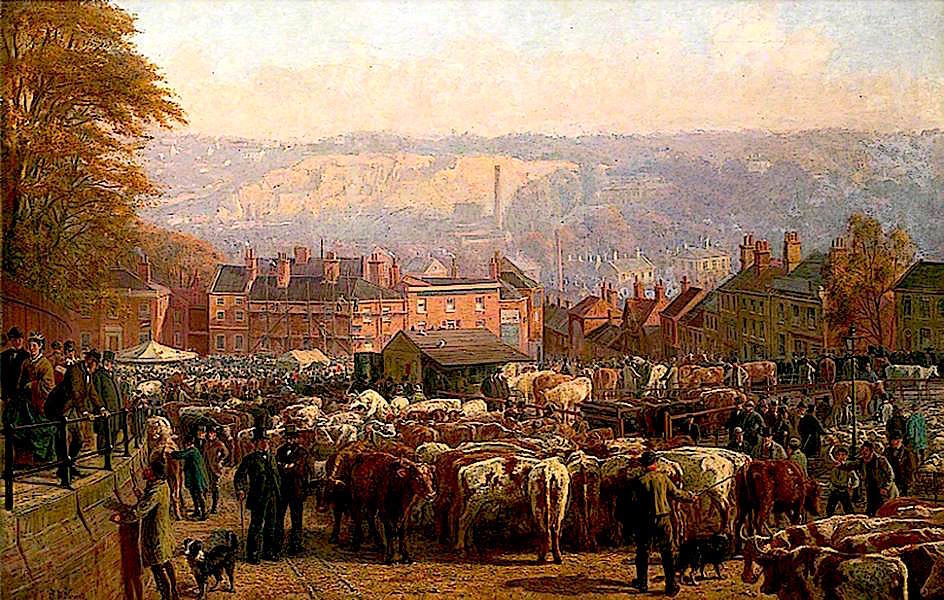

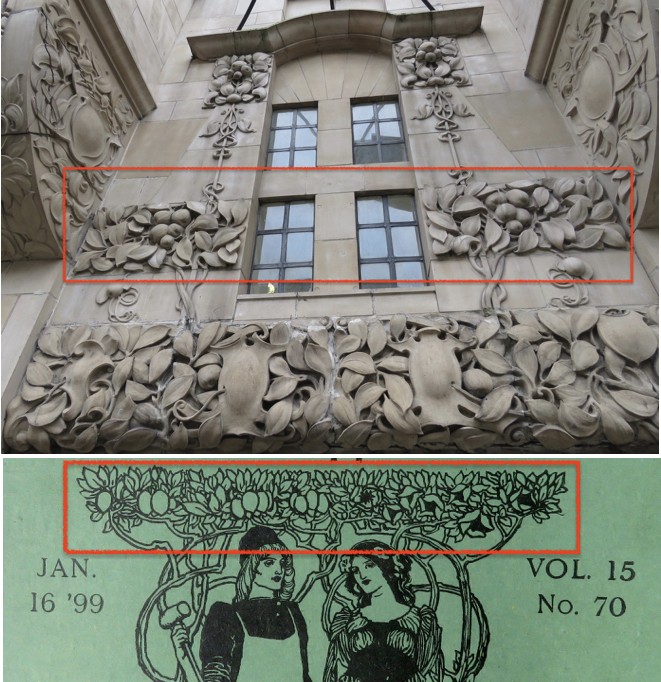

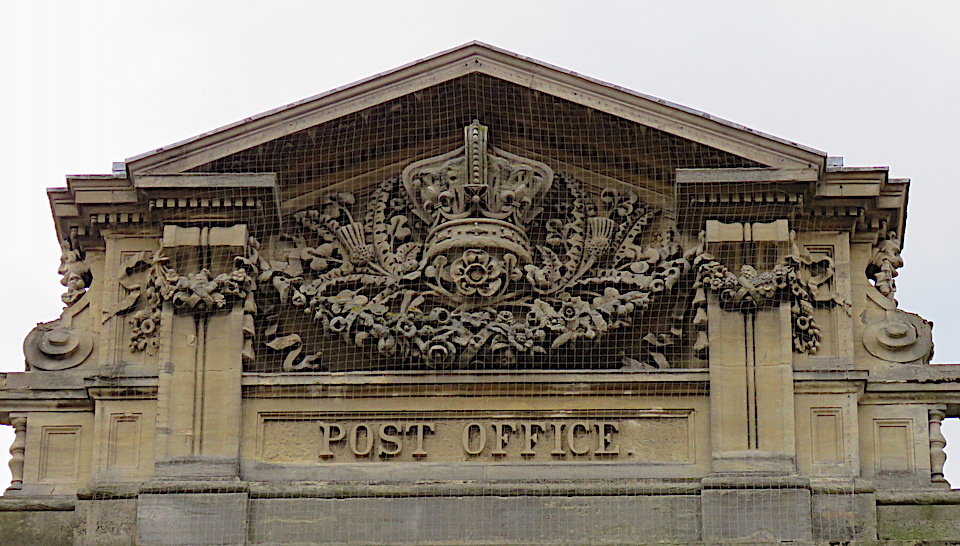

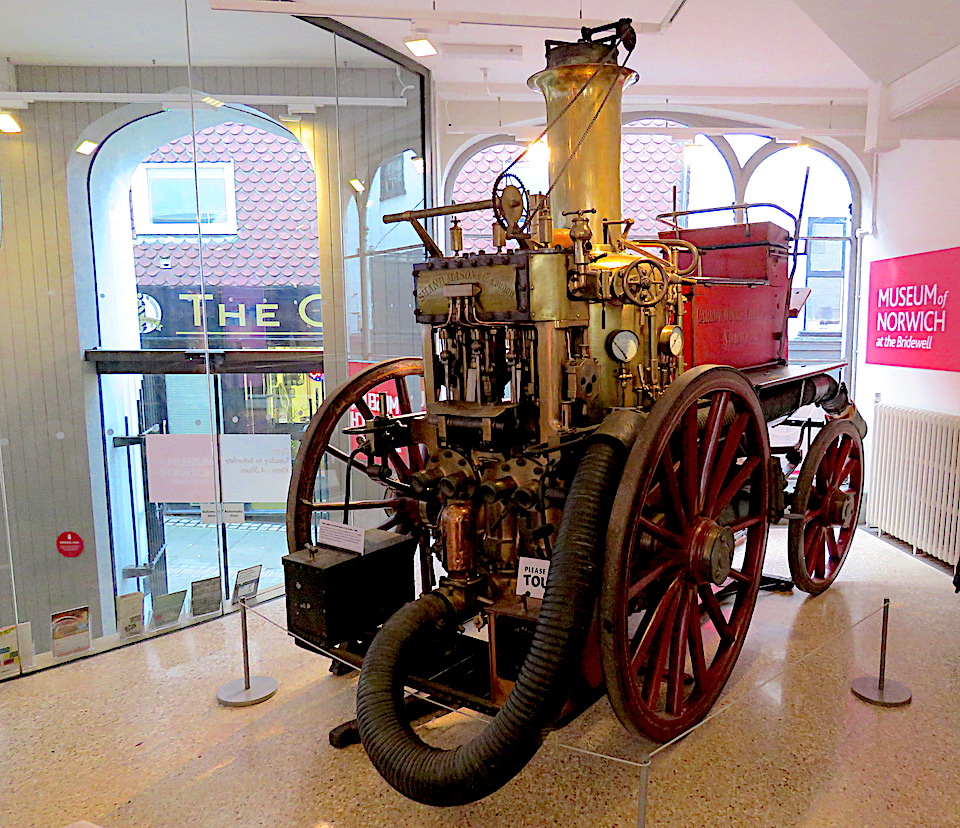

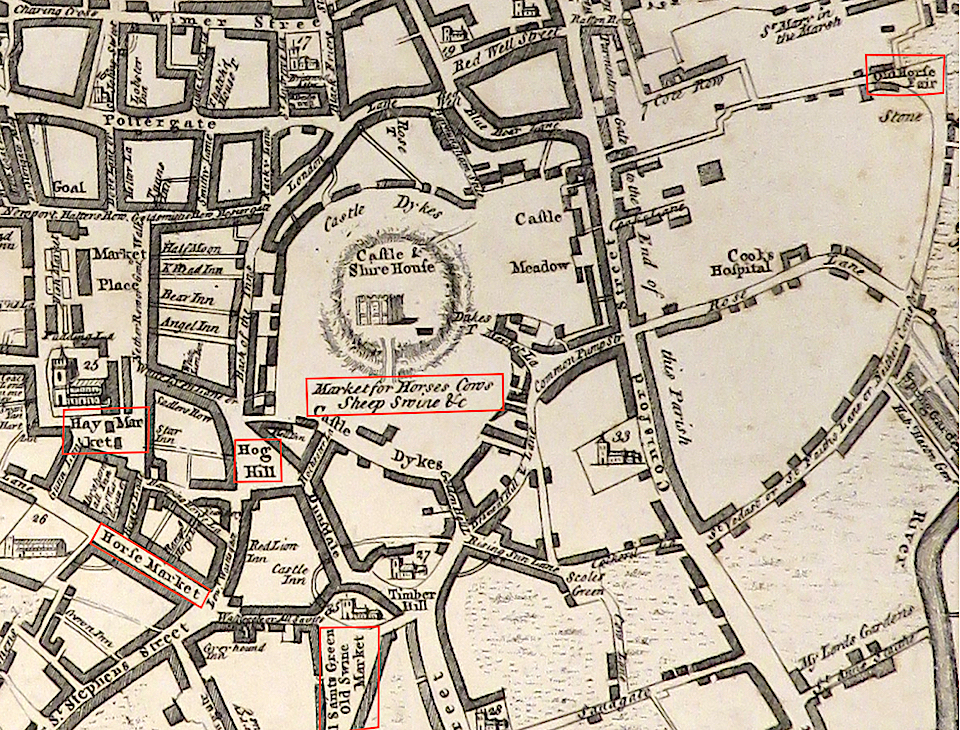

At one time the castle was ringed by various livestock markets for which the Agricultural Hall of 1882 provided formal focus. The sloping plain outside the Hall stands at the top of Prince of Wales Road, a wide, curving street. It was built in 1865 to connect Norwich Thorpe Railway Station to the city; it was never finished as planned and is only graceful in parts. However, the buildings on the plain at the top of the road ‘dignify the new entry to the city’ [5]. From the left (below) we see: part of Barclays Bank – a huge banking hall designed like a Roman palazzo by the local firm of E Boardman & Son with Brierley & Rutherford of York (1929); next, a monument to the Boer War – the statue of Peace sculpted by George and Fairfax Wade (1904); then the Royal Hotel, another local masterpiece by the Boardmans (1896-7), decorated in moulded red brick from Gunton’s Costessey Brickworks [6]. To the right we get a glimpse of the Agricultural Hall itself. It was built in 1882 in local red brick and alien red Cumberland sandstone, again relieved with decorative Cosseyware.

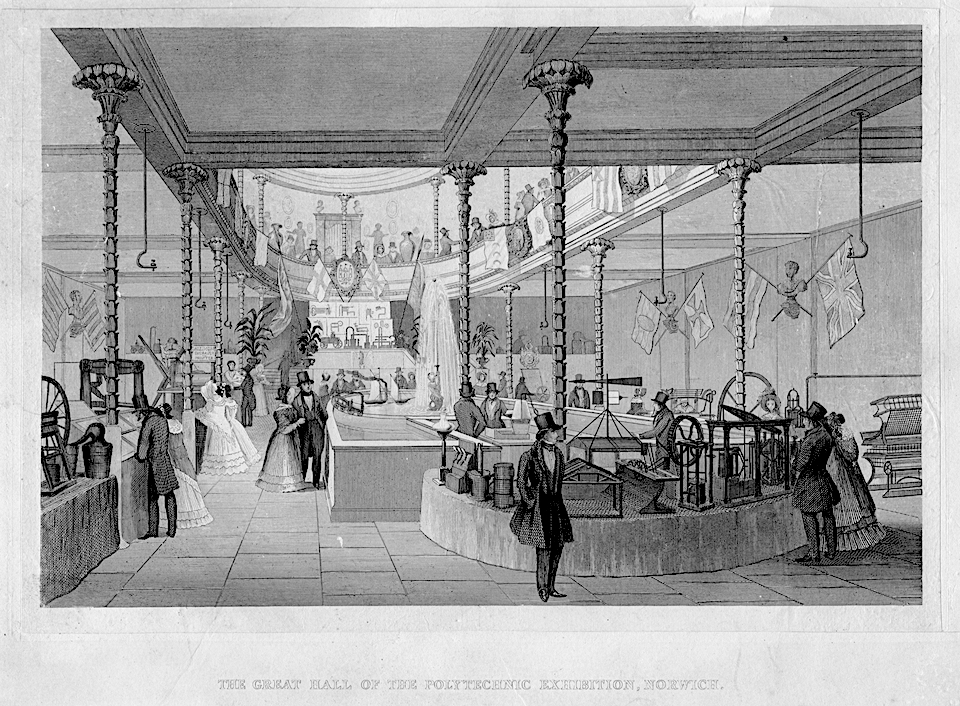

The Agricultural Hall was inaugurated in 1882 by the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, who was Patron of the Norwich Fat Cattle Show Association. This was the year that Oscar Wilde started his lecture tour of America where one of his topics was ‘The House Beautiful’. Two years later he came to the Agricultural Hall to deliver the same lecture, no doubt well received by cattlemen on both sides of the Atlantic.

Just visible to the left is the former Crown Bank of 1866 built by Sir Robert Harvey. As we saw in The Norwich Banking Circle, Harvey named his Crown Bank after the Crown Point estate, just outside the city at Whitlingham. The estate was bought from the aptly named Major Money – intrepid balloonist and someone who had served in the army at Crown Point fort in North America.

Before we leave Agricultural Hall Plain we should take some cheer from knowing that Laurel and Hardy stayed in the Royal Hotel in 1954.

Looking out from the Hall (now Anglia TV), across Agricultural Hall Plain, is its conjoined twin – Bank Plain.

On the site now occupied by the former Barclays Bank stood its predecessor, Gurney’s Norwich Bank, established in the late C18.

At the time, the open space was called Redwell Plain but after Gurney’s opened it became known as Bank Plain. The well is still commemorated in Redwell Street, which runs between Bank Plain and St Andrew’s Street.

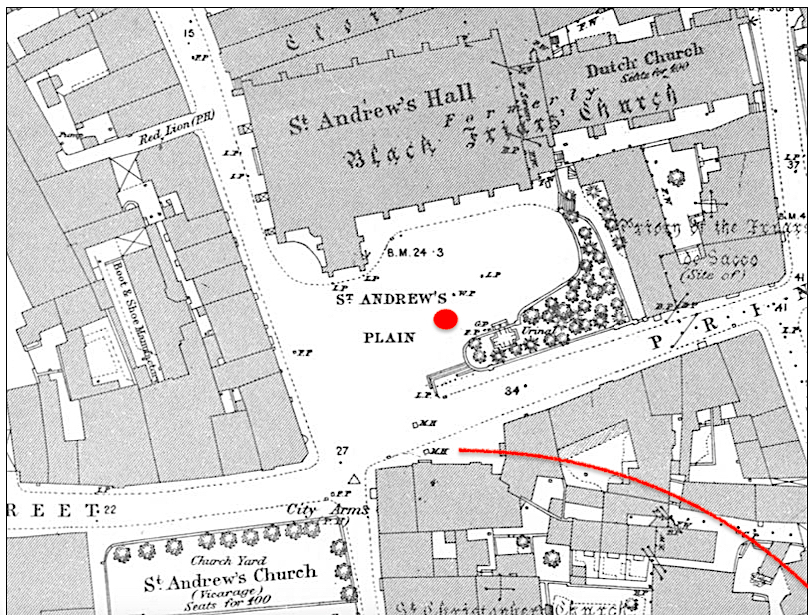

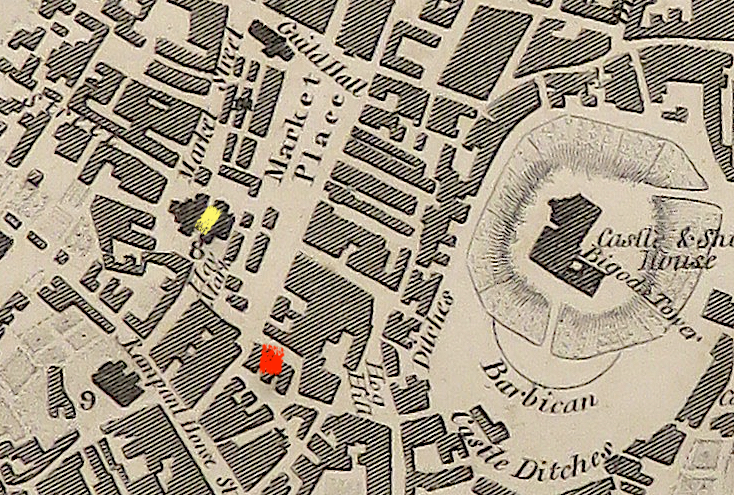

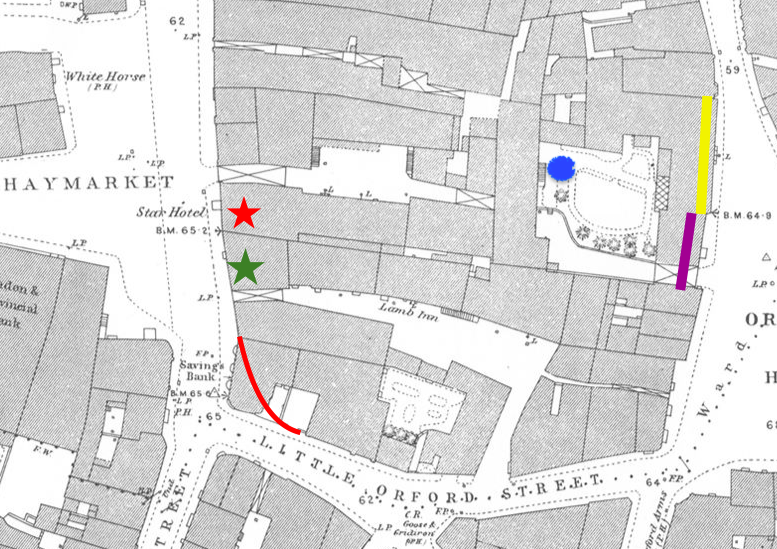

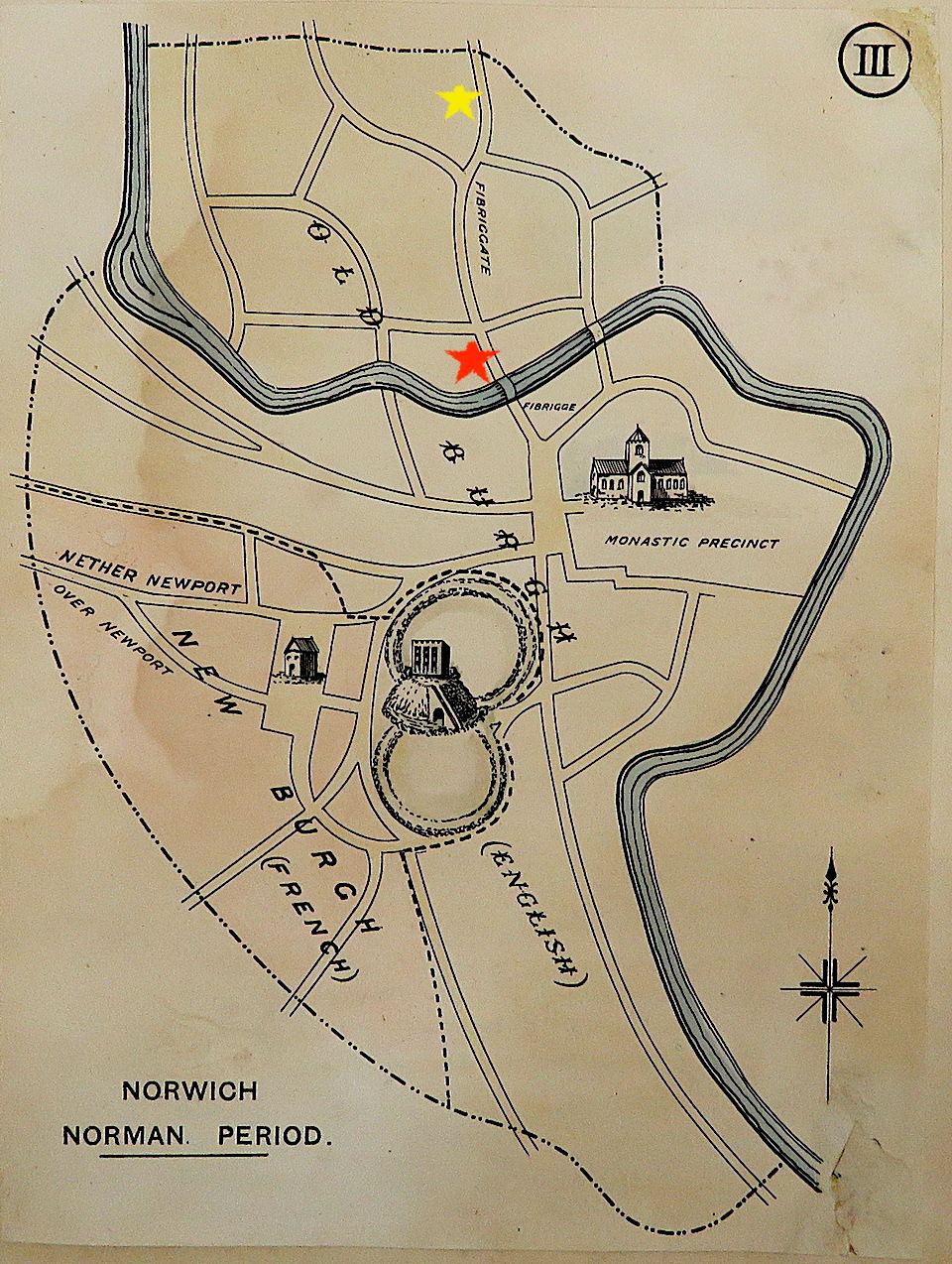

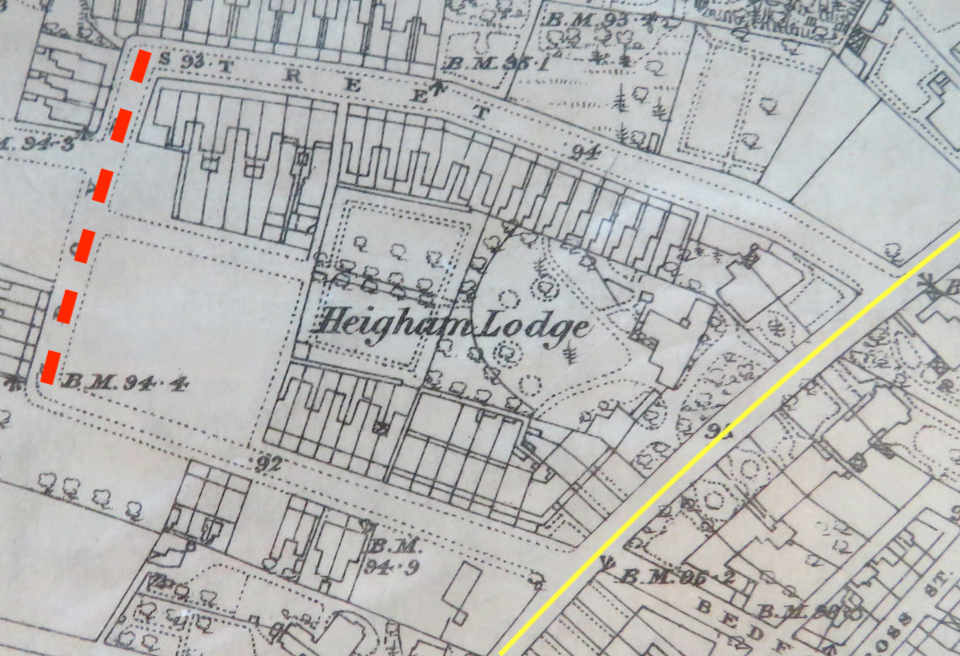

Today, it is possible to travel to St Andrew’s (Hall) Plain by following the bend in the road down the hill to Suckling House/Cinema City. But, as the map shows, this extension of St Andrew’s Street did not exist in 1884; it was created so that the new electric trams, which ushered in the twentieth century, could avoid the tight corner where Redwell Street meets Princes Street.

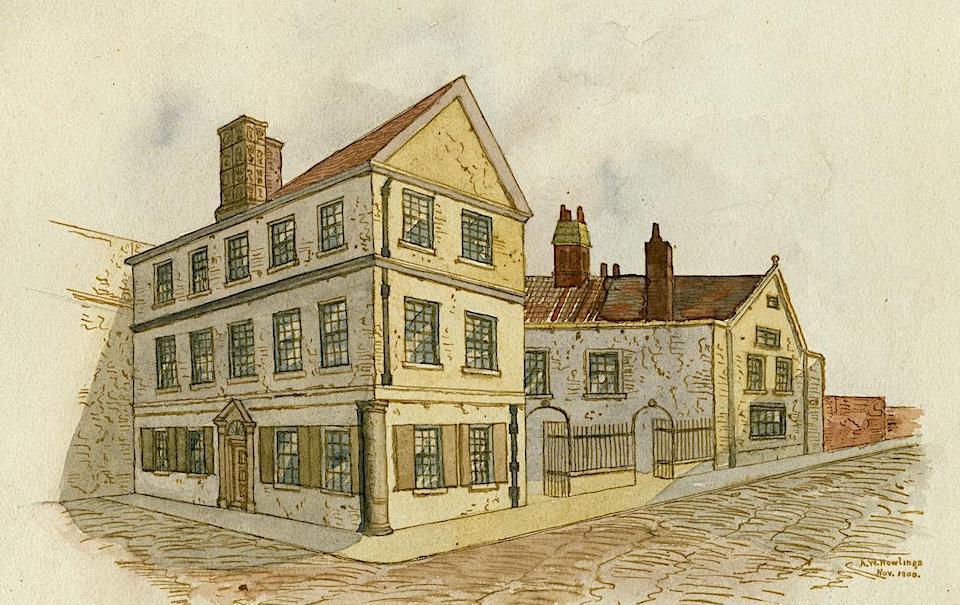

Garsett House – also known as Armada House since it was reputedly built from the timbers of a ship wrecked during the Spanish Armada – was bisected in the process.

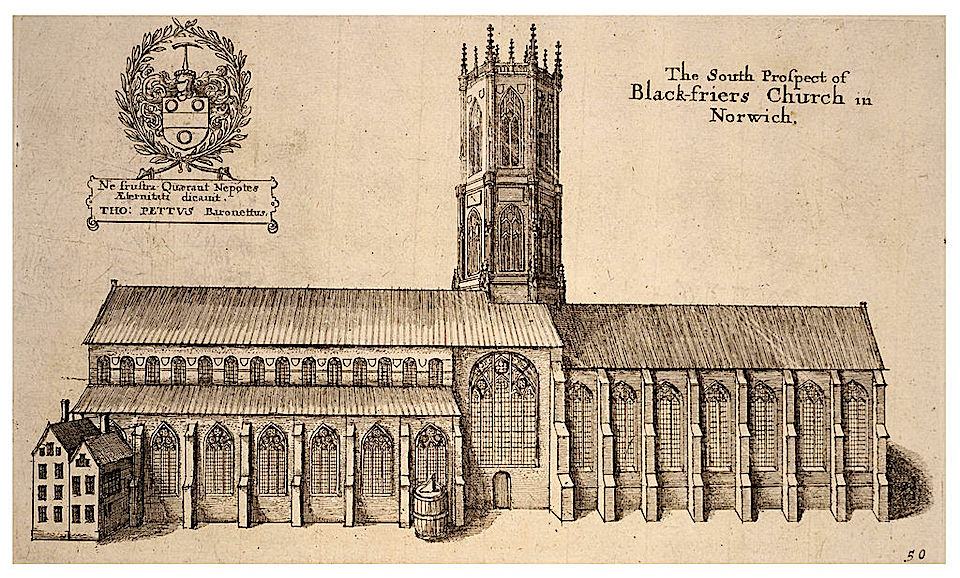

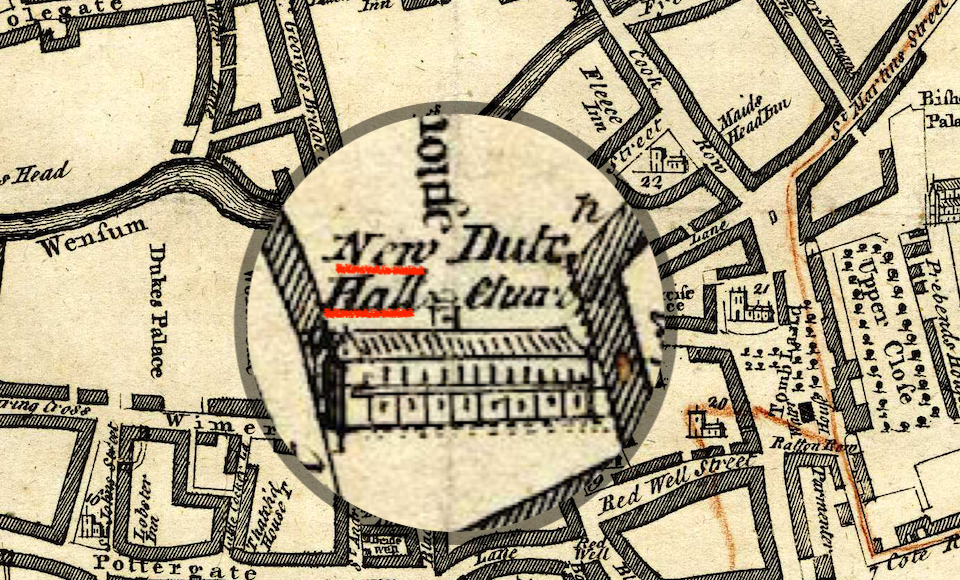

St Andrew’s Hall is the nave of what was the Blackfriar’s or Domican church of Norwich – the most complete surviving medieval friary in England. Present-day Blackfriars Hall was formerly the friars’ chancel and, as the map above indicates, was also once the church of the Dutch-speaking community [1].

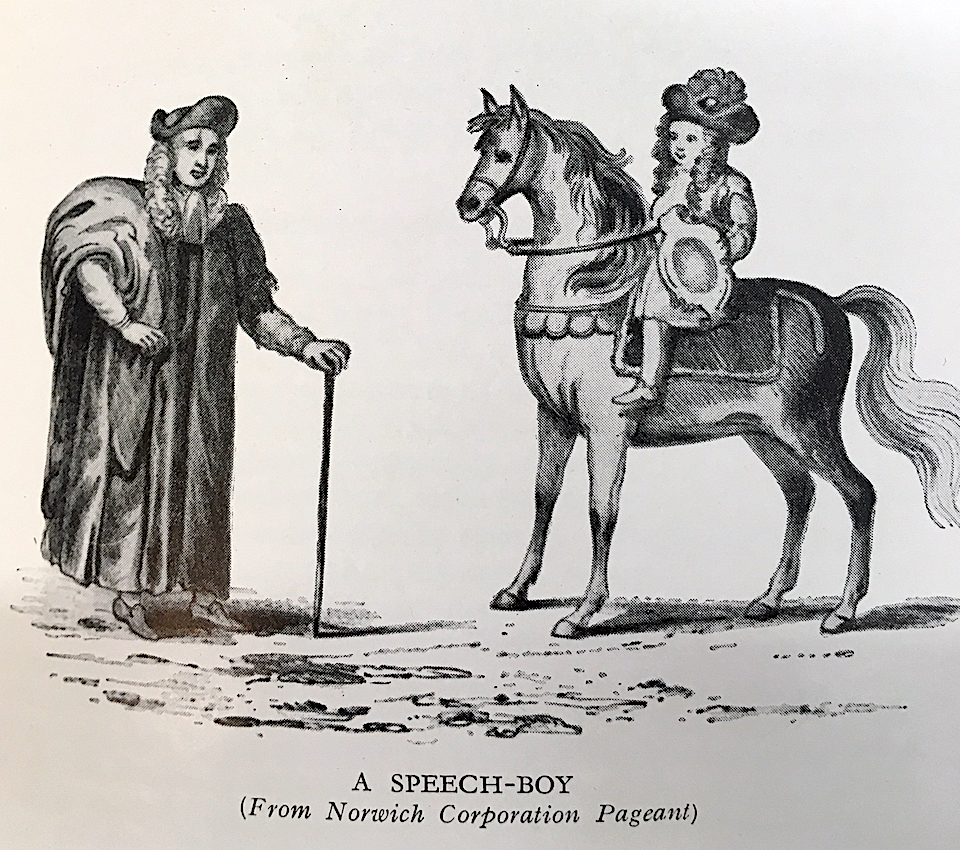

The engraving by Wenceslas Holler (1607-1677) shows the nave and chancel meeting beneath an octagonal tower that collapsed in 1712. Home to the ‘Order of Preachers’, as the Dominican Friars are known, the large internal volume of St Andrew’s Hall was designed for spreading the word [7]. Outside, St Andrew’s Plain was also used as a preaching yard but during Kett’s Rebellion it witnessed less peaceable activity for it was on the plains, rather than the tortuous medieval alleyways, that pitched battles could be fought. Sotherton saw the rebel bowmen let loose ‘a mighty force of arrowes’… ‘as flakes of snow in a tempest’ but Captain Drury’s band of arquebusiers, with their early versions of the musket, replied with ‘such a terrible volley of shot (as if there had been a storm of hayle)’, leaving about 330 dead [2]. St Andrew’s Hall was used as stables until the uprising was quelled.

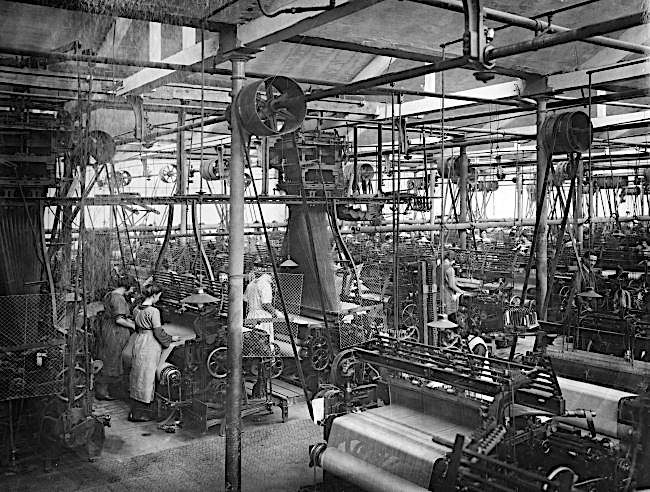

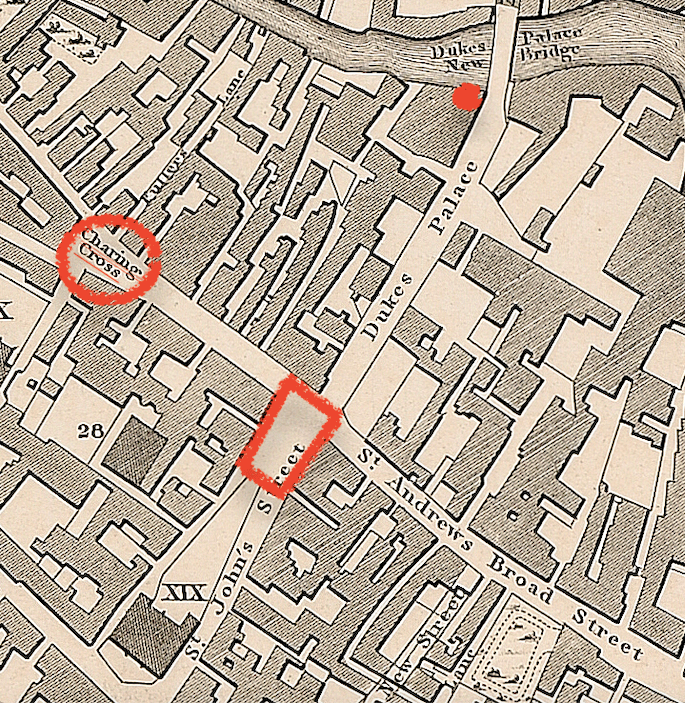

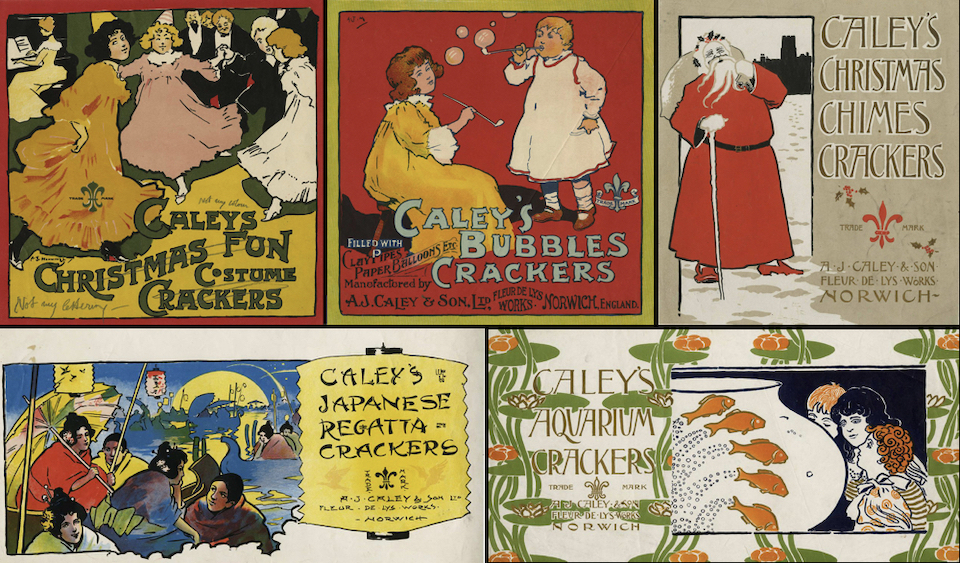

Maddermarket Plain is one of the city’s smaller plains [4]. It is situated at the junction of St Andrew’s Street, Duke Street, St John Maddermarket (formerly St John’s Street) and Charing Cross. The latter two names provide a thumping clue to the history of this district. ‘Charing Cross’ is thought to be a corruption of ‘shearing’ – the process where the raised pile on woollen cloth was cut to a standard height with shears. ‘Madder’, of course, refers to the red/deep pink dye derived from madder roots and used to colour fabric the famous ‘Norwich Red’.

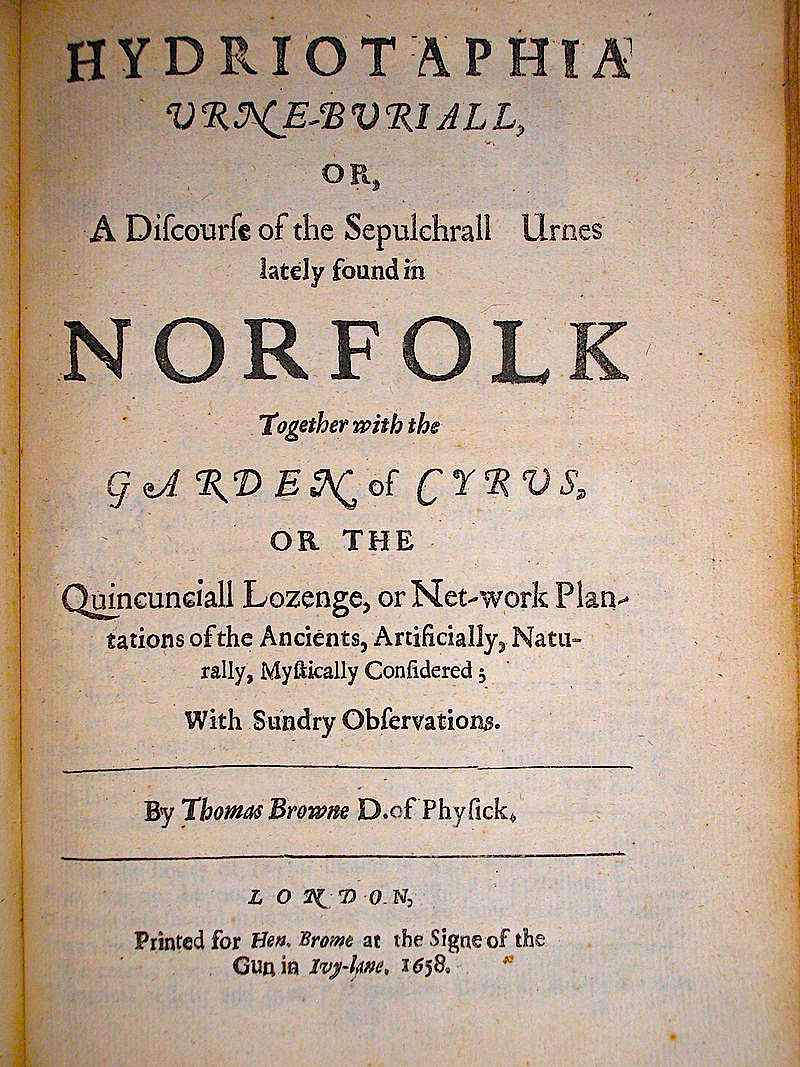

The Charing Cross/Westwick Street area was at the heart of the textile industry [4] and the river was where its waste products ended up. Just above Charing Cross on the map is Fuller’s Lane – fulling being a process in which cloth is cleaned. In a previous post [8] we saw that in the C19 the master dyer Michael Stark emptied his dye vats into the Wensum from his factory next to the Duke’s Palace Bridge but this kind of pollution had been happening for centuries. On his journeys through England in 1681 Thomas Baskerville noted that the duke’s great townhouse was ‘seated in a dung-hole place’, surrounded by tradesmen cleaning and dyeing cloth [9]. The palace was later abandoned.

At the beginning of the 1500s, Norwich had been devastated by two fires that destroyed over 1000 houses [10]. The extent of the damage was such that some 70 years later the mayor was discussing how to deal with unrestored plots. When Queen Elizabeth I visited Norwich in 1578 she commented on the number of derelict properties despite the steps taken to shield her from the worst. To convey her from the Marketplace to the Cathedral (centuries before Exchange Street was open) the east wall of St John’s Maddermarket was rebuilt in order to widen the street [4].

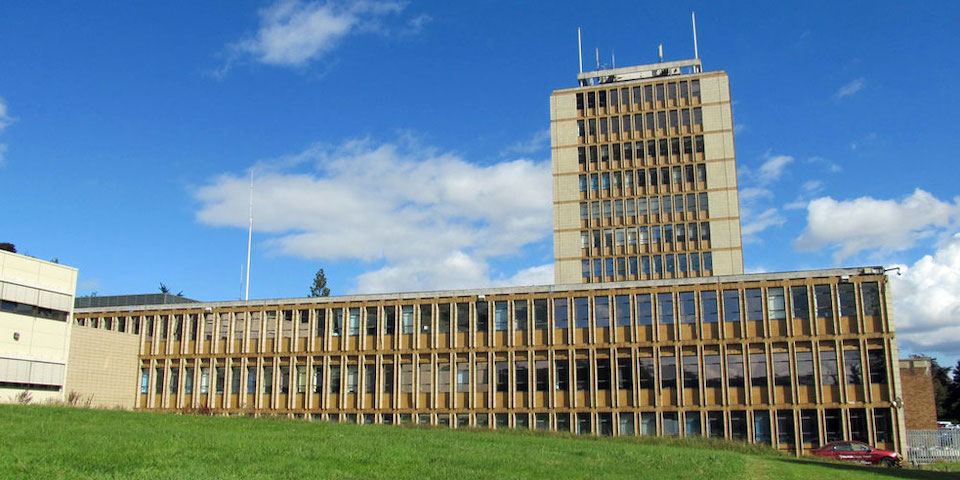

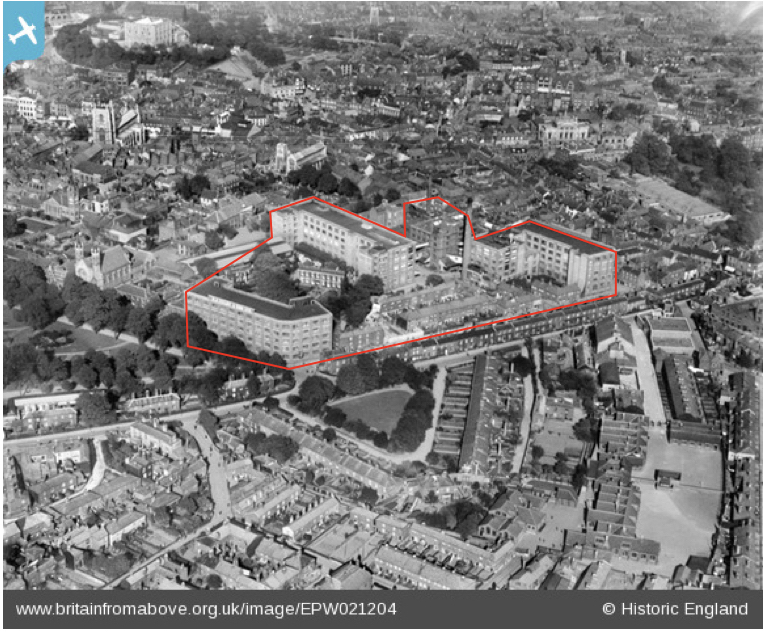

In his book, Richard Lane [4] skips forward a few centuries to end with the last recorded plain of the twentieth century. This is University Plain, the site of the University of East Anglia where Sir Denys Lasdun built his 1960s paean to concrete. You might imagine the plain to be an open meeting space, such as the amphitheatre-like Central Court, but it appears to refer to the large site as a whole.

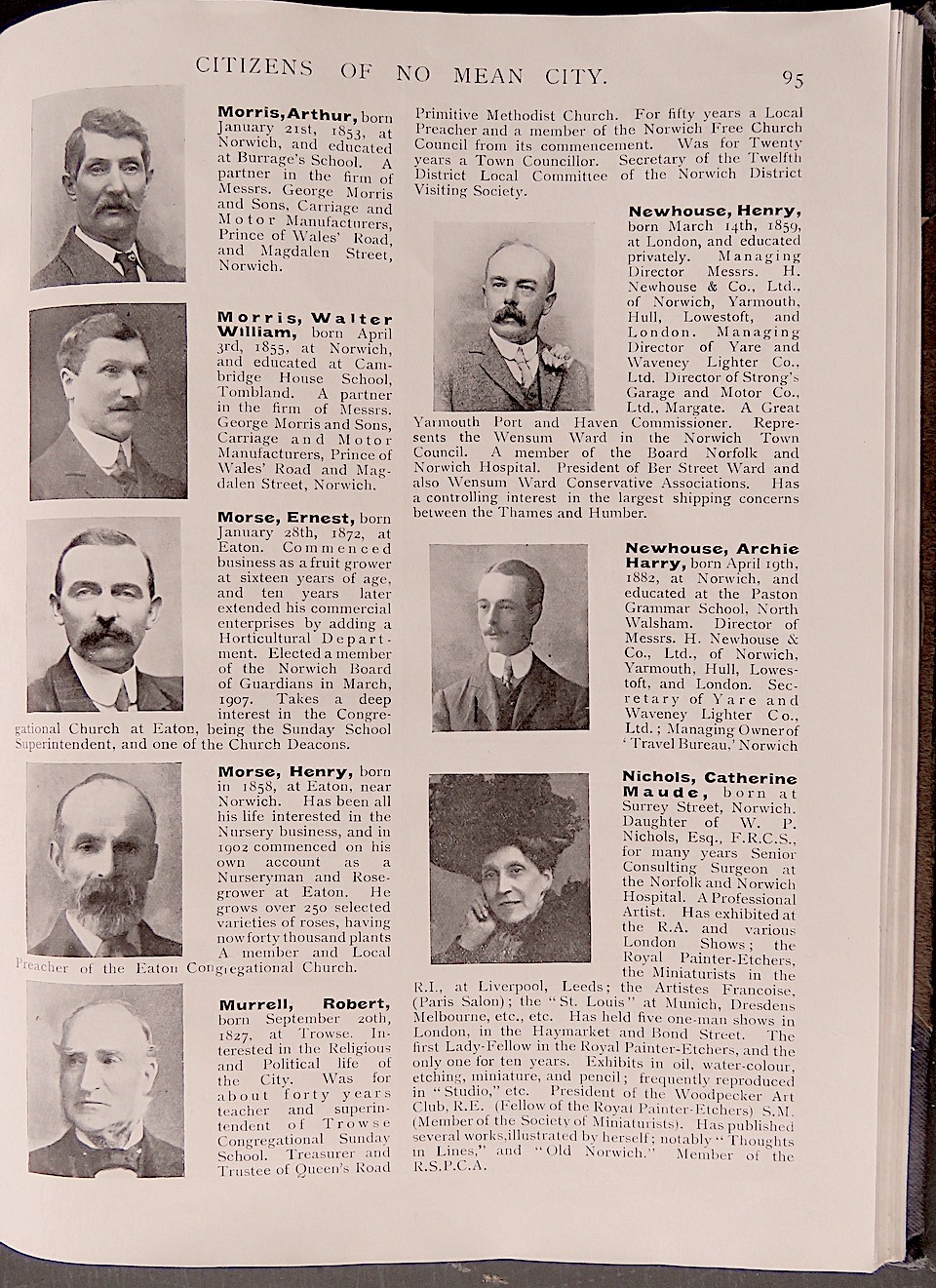

The use of the word ‘plain’ continues into the twenty-first century. In 1771 William Fellowes, a wealthy and philanthropic squire, built in Shotesham (ca. eight miles south of Norwich) what is claimed to be the earliest cottage hospital in England. Benjamin Gooch was the first surgeon and he, together with Fellowes, went on to propose a new general hospital for the city of Norwich. Designed by local architect William Ivory, the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital was built just outside the city wall at St Stephen’s Gate on land provided by the council at a nominal rent. Fellowes laid the foundation stone in 1771 and it was completed in 1775.

In 2003 a new hospital was built on the outskirts of Norwich at Colney leaving the old N&N site to be developed for housing by Persimmon Homes on the newly-coined Fellowes Plain [11].

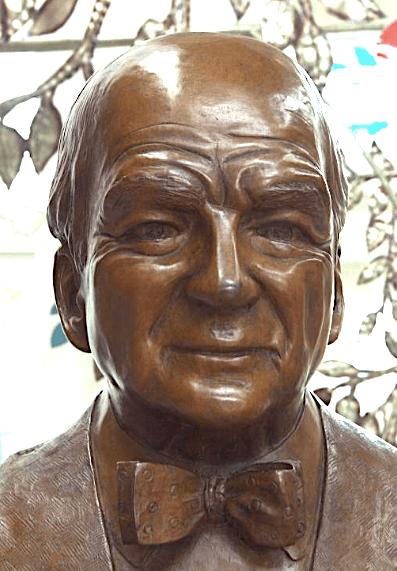

The word ‘plain’, as applied to Fellowes Plain, seems to refer to the entire site although three open spaces within this are named ‘plain’ in their own right. The first is Kenneth McKee Plain, dedicated to Ken McKee CBE (1906-1991), orthopaedic surgeon at the N&N who pioneered the total hip replacement.

The second is Edward Jodrell Plain. Dozens of searches provide no insight beyond repeating the salient fact that he was a major benefactor. The Jodrell family of Bayfield Hall, near Holt, were known to have been benefactors to the N&N [13]. As far back as 1814 Henry Jodrell left £200 to the hospital in his will. His nephew Edward (1785-1852) and Edward’s son Captain Edward Jodrell have the necessary forename but it was Captain Jodrell’s youngest son Alfred who seems best remembered for his philanthropy. He sent baskets of fruit and vegetables each week to the hospital and at Christmas gave 40 oven-ready chickens and the same number of turkeys, underlining the Jodrells’ tradition of giving to the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital.

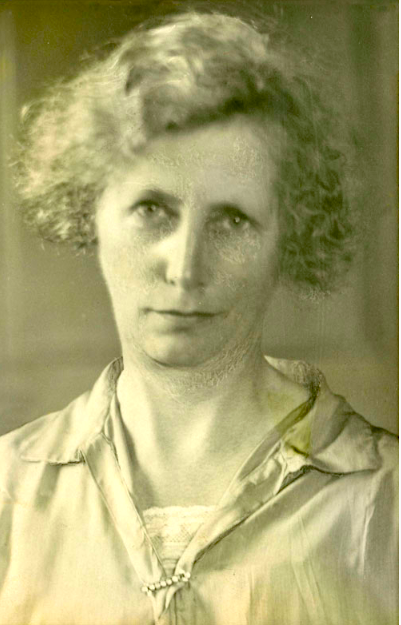

The third plain on the site of the old hospital is the large green known as Phillipa Flowerday Plain.

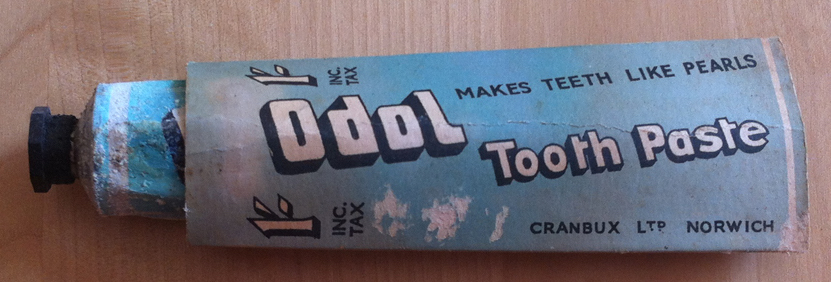

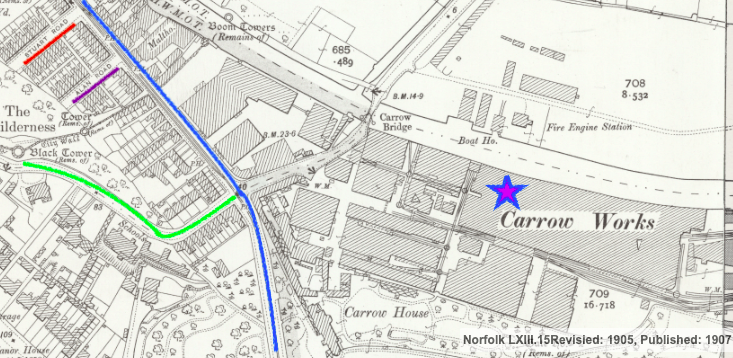

Before being employed by Colmans at their Carrow Works, Phillipa Flowerday (1846-1930) trained and worked as a nurse at the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital. According to Rod Spokes, former Colmans manager, when the company’s dispensary was founded in 1864 a man was employed to visit male employees at home and report on cases of need. In 1872, Phillipa was employed to visit the families of the workpeople as well as assisting the doctor in the dispensary. She is therefore celebrated as the first industrial nurse in the country [14].

To be continued …

©2020 Reggie Unthank

Sources

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/08/15/going-dutch-the-norwich-strangers/

- https://archive.org/stream/kettsrebellionin00russuoft/kettsrebellionin00russuoft_djvu.txt

- http://www.norwich-heritage.co.uk/norwich_maps/Norwich_map_1884_zoomify.htm

- Richard Lane (1999). The Plains of Norwich. Pub; Lanceni Press, Fakenham.

- Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson (1997). The Buildings of England. Norfolk I. Norwich and North-East. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/05/05/fancy-bricks/

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1220456

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/07/15/the-bridges-of-norwich-1-the-blood-red-river/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/12/15/the-absent-dukes-of-norfolk/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2019/12/15/norwich-shaped-by-fire/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norfolk_and_Norwich_Hospital

- http://www.racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp?action=getsurvey&id=797

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayfield_Hall

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philippa_Flowerday

Thanks: I was inspired to write this post by Richard Lane’s excellent book on Norwich Plains and I have drawn upon it freely. I am grateful to Clare Everitt of Picture Norfolk for permissions and the George Plunkett website for the use of photographs. I am grateful to Rod Spokes for information about the Colmans dispensary.

![Orford Hill 16 Livingstone Hotel [1361] 1936-08-30.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/orford-hill-16-livingstone-hotel-1361-1936-08-30.jpg)

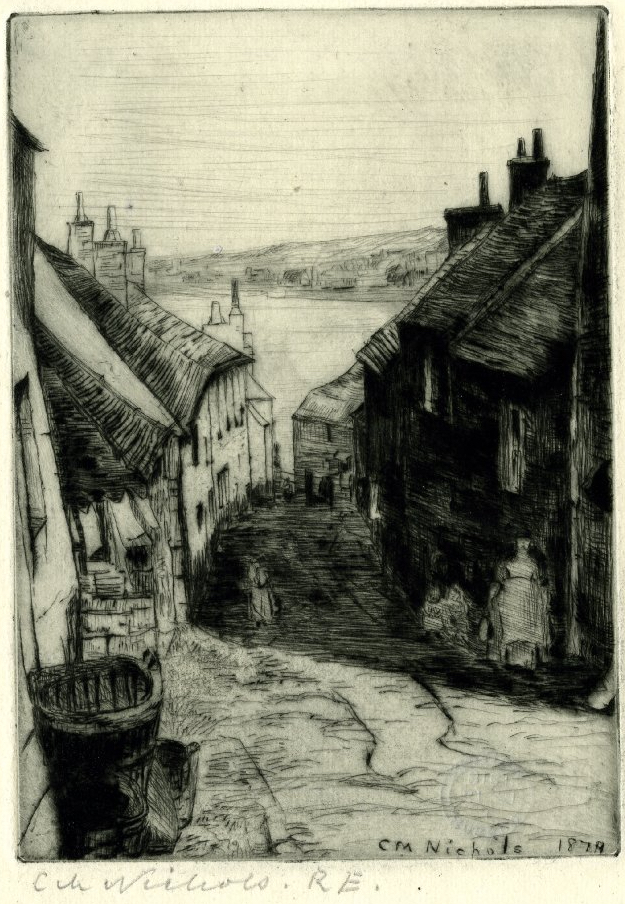

![Colegate Burrell's Yard view south [2030] 1937-10-09.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/colegate-burrells-yard-view-south-2030-1937-10-09.jpg)

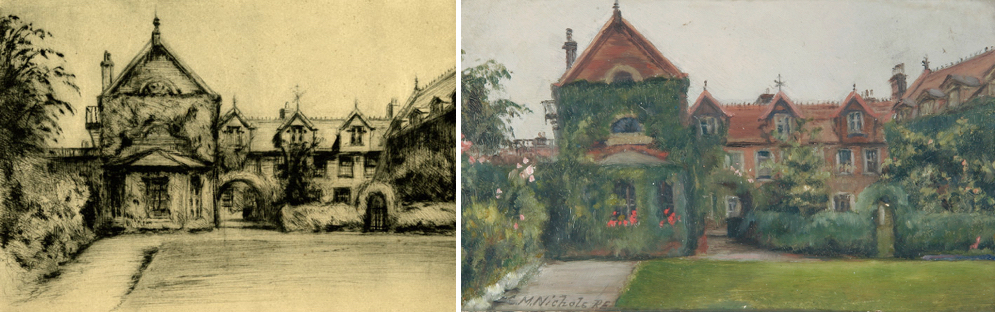

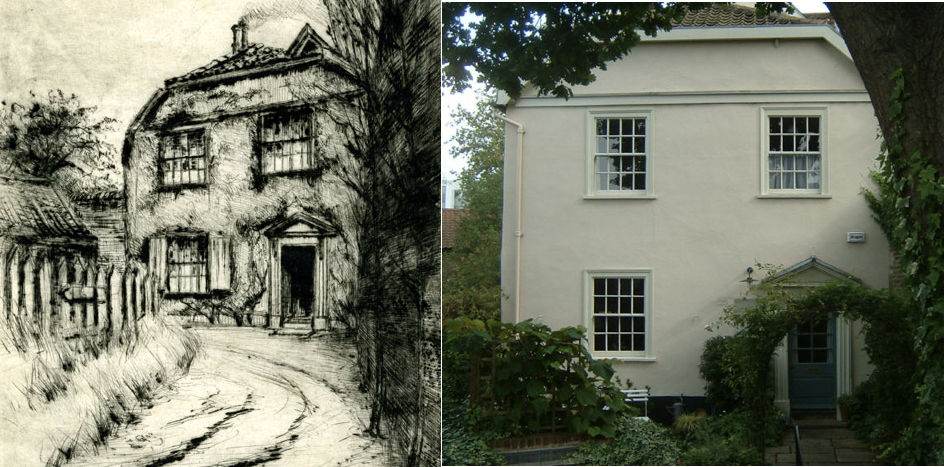

![Catton Catton Place [0610] 1935-08-05.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/catton-catton-place-0610-1935-08-05.jpg)

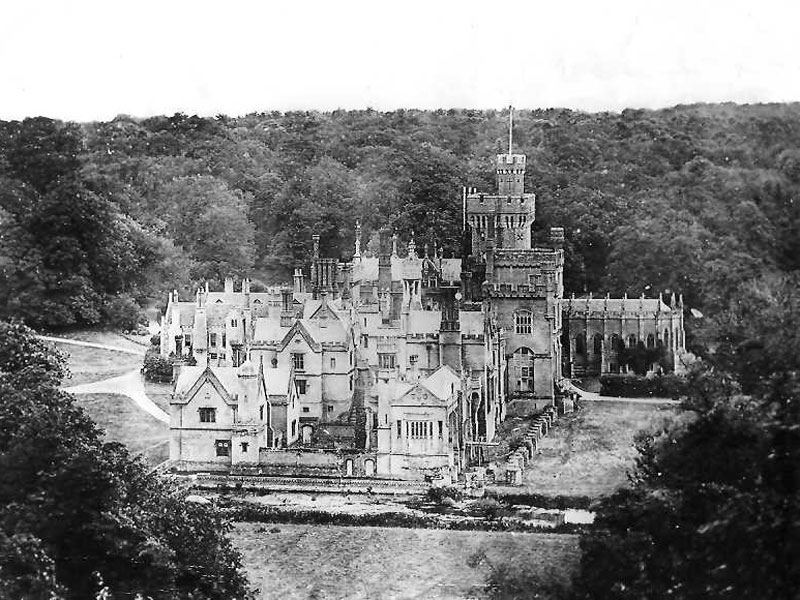

![Keswick Hall south front [6606] 1990-04-30.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/keswick-hall-south-front-6606-1990-04-30.jpg)

![Tombland 29 site of Popinjay Inn [4659] 1962-03-28.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/tombland-29-site-of-popinjay-inn-4659-1962-03-28.jpg)

![Pottergate 12 to 16 fire station entrance [B504] 1933-03-26.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/pottergate-12-to-16-fire-station-entrance-b504-1933-03-26.jpg)

![1934-05 construction almost complete [0093] 1934-05-10.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/1934-05-construction-almost-complete-0093-1934-05-10.jpg)

![Mountergate St Faith's House [1168] 1936-07-27.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/mountergate-st-faiths-house-1168-1936-07-27.jpg)

![Thorpe St Andrew Thorpe Lodge [5423] 1974-09-14.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/thorpe-st-andrew-thorpe-lodge-5423-1974-09-14.jpg)

![Surrey St 32 Regency Georgian doorway [0468] 1935-04-19.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/surrey-st-32-regency-georgian-doorway-0468-1935-04-19.jpg)

![Surrey St 30 to 34 [1028] 1936-06-14AA.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/surrey-st-30-to-34-1028-1936-06-14aa.jpg)

![Surrey St 47 to 79 Carlton Terrace [6461] 1987-05-19.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/surrey-st-47-to-79-carlton-terrace-6461-1987-05-19.jpg)

![Cattle Market view NE from Market Avenue [4541] 1960-03-12.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/cattle-market-view-ne-from-market-avenue-4541-1960-03-12.jpg)