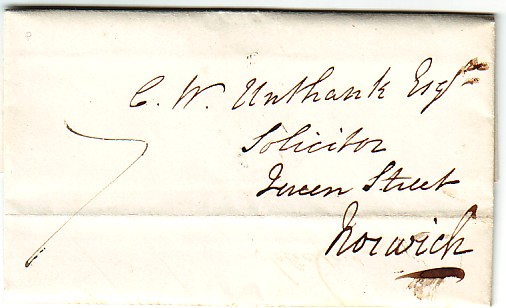

Regular readers will know that I have been chipping away at the urban myth that claims a piece of tall wall at the Unthank Road/Clarendon Road junction to be the last remnant of the Unthank’s Heigham estate. Days after my last post on this topic I was still unable to confirm or deny the story … but then I stumbled across new evidence.

The double-height wall said to be the last vestige of the Unthanks’ Heigham estate

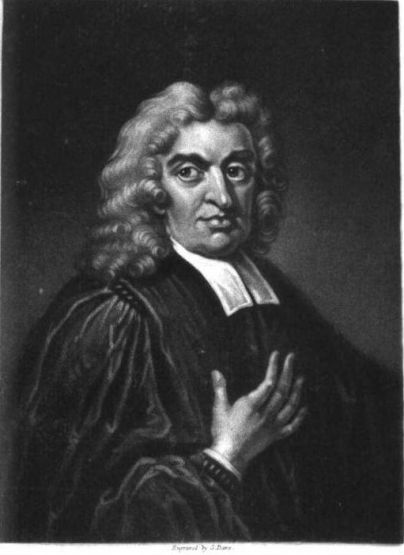

The story seems to have originated with Reverend Alfred Jonathan Nixseaman (1886-1977), vicar at Intwood Church, a field away from Intwood Hall on the southern outskirts of Norwich.

Intwood Hall from the churchyard

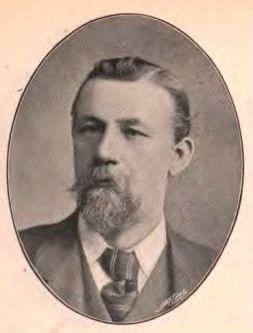

William Unthank’s son and heir, Clement William, moved to the Hall when his wife took possession of her family home in 1855. William Unthank (1760 – 1837) was buried in St Bartholomew’s church Heigham but his descendants are buried at Intwood church. Reverend Nixseaman was the incumbent there when the last of the Norwich Unthanks (Miss Margaret Beatrice Unthank d.1995) lived in the Hall.

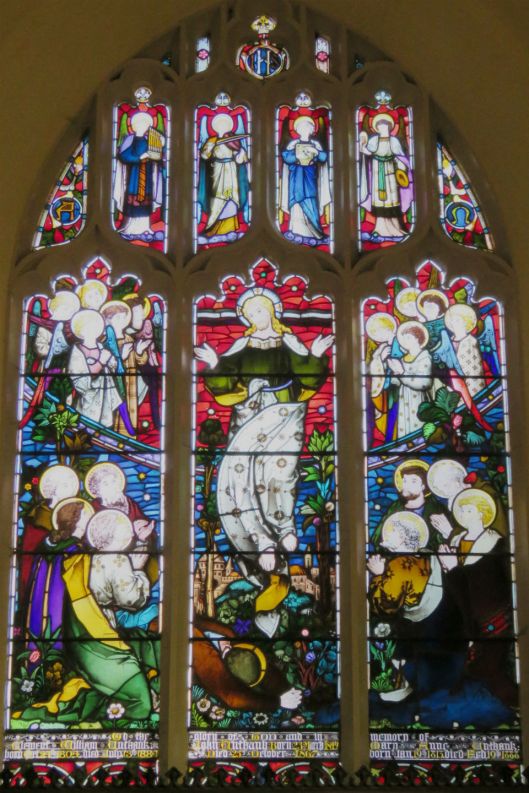

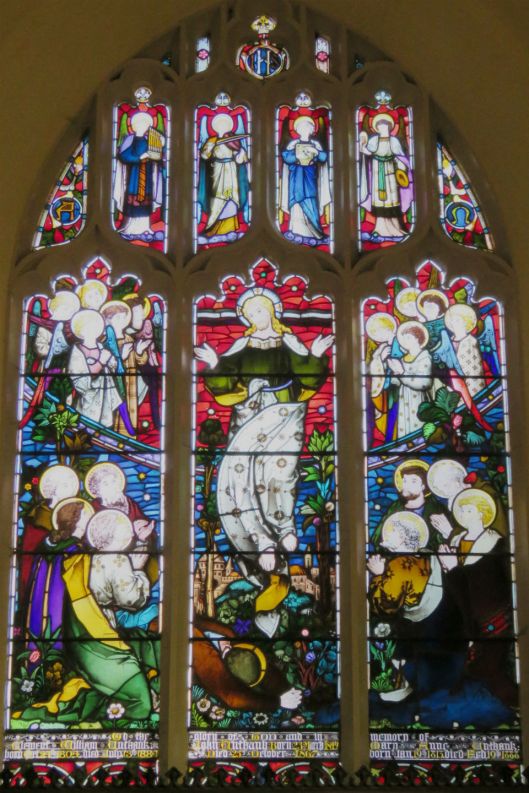

Memorials in Intwood church to the Unthanks of Intwood Hall. Clement William moved from Heigham to his wife’s Intwood estate when their son, CWJ Unthank, was a young boy.

The Unthank memorial window in Intwood church

Nixseaman’s familiarity with the details of the Unthanks’ lives, and deaths, lends an air of authority to his self-published book, The Intwood Story (1972) [1]. He described in quite some detail the newly-built house to which William Unthank moved in 1793; its sylvan setting in the “highest part of Heigham”; a house with 70 acres of grass and woods.

“This Heigham House became the home of the Unthanks for about 100 years, from 1793 to 1891. It stood in its own Park grounds not far from St Giles’ Gates (at the top of Upper St Giles Street). Later when the estate was sold up piece-meal a terrace of houses was built on the site … All that now remains of the premises is some walling which formed part of the stables, seen at the corner of Ampthill Street, opposite Clarendon Road.” Later, “This old wall now shelters the surgery and residence of Dr A.G.Day (38 Unthank Road) from the roadway.”

This is where the myth of The Wall began According to Reverend Nixseaman, William Unthank’s Heigham House was unambiguously situated at the corner of modern-day Clarendon Road and Unthank Road. But even if we ignore the slight niggle that Ampthill Street is not opposite Clarendon Road there are enough other inconsistencies to have sent me on a wild-goose chase around various other Heigham Houses, Halls and Lodges of Victorian Norwich, as my previous blogpost on the topic demonstrates [2]. For instance: Clement William and his wife, Mary Anne Muskett, did not live in this particular Heigham House from 1835 to 1855 for according to the 1842 tithe map they lived 1000 yards away on their estate near modern-day Onley Street; Clarendon Road, Grosvenor Road, Neville Street and Bathhurst Road were eventually built on this site, not “a terrace of houses”; and other evidence indicates that brewer Timothy Steward was living in Heigham Lodge from 1836 onwards.

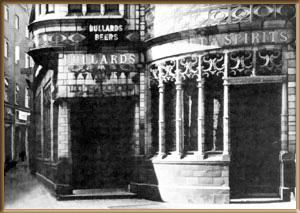

‘Steward’s House’ at the corner of Clarendon and Unthank Roads

The S in the S&P Limited refers to Timothy Steward, brewer. From the Eaton Cottage public house at the junction of Unthank Road and Mount Pleasant

In that previous blogpost on the Unthanks, when I was still contorting myself to accommodate Nixseaman’s plausible-sounding testimony, I speculated that William and Clement William might have had separate houses and that William sold his to Timothy Steward towards the end of his life. I therefore looked at the Land/Window Tax records for the parish of Heigham to check whether Steward ever lived in Unthank’s house. In every annual entry from 1790 to 1832, when the NRO’s records unfortunately stop, William Unthank is recorded as Proprietor and Occupier of House and Land. Unfortunately, the number and name of the house was never specified in these records. In 1832, Timothy Steward also makes an appearance but his entry (Proprietor and Occupier of House and Land) is the same as Unthank’s indicating that both were owner-occupiers, implicitly of separate houses.

Puzzlement about the exact site of the Unthanks’ house is not a new thing for on the 25th of May 1934 a correspondent to the Eastern Daily Press wrote:

“In reply to S.B. about 60 years ago Colonel Unthank’s House was near Mount Pleasant and, if my memory is correct, was in the space now occupied by Gloucester, Bury and Onley Streets. His grounds were enclosed by a brick wall and the house was some distance from the road (i.e., in contrast to Timothy Steward’s House whose carriage drive was close to the road). The Unthank Arms, at the top of Newmarket Street, at one time bore, as a sign, the elaborate armorial bearings of the Unthanks, so we may, I think, assume with some confidence that the family existed in the neighbourhood. Yours faithfully, W,B.”

In the same edition, a letter from William Unthank’s grandson, Clement William John Unthank (b 1847), should have settled the argument but appears not to have been seen by Nixseaman:

“My grandfather bought Heigham House and 70 acres of land between what is now Trinity Street and Mount Pleasant about 1793.”

This location for Heigham House is consistent with Rye’s History of the Parish of Heigham [3] that states: “Unthank’s house was on the other side of the road (to Timothy Steward’s), and was in well-wooded grounds.” It now looks as if Reverend Nixseaman, writing 100 years after the Unthanks left the parish, chose the wrong Heigham House on which to pin his imaginative account of their home.

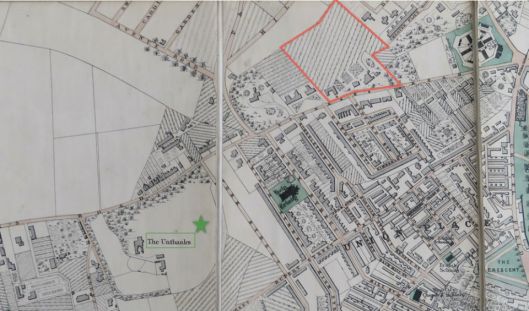

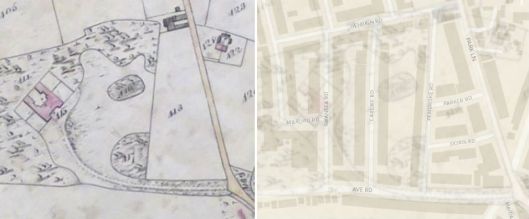

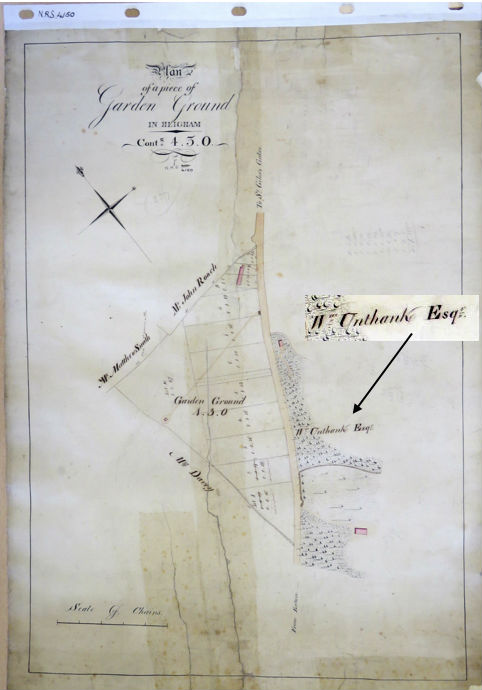

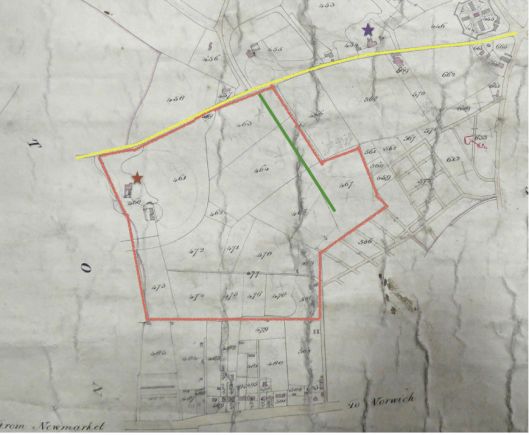

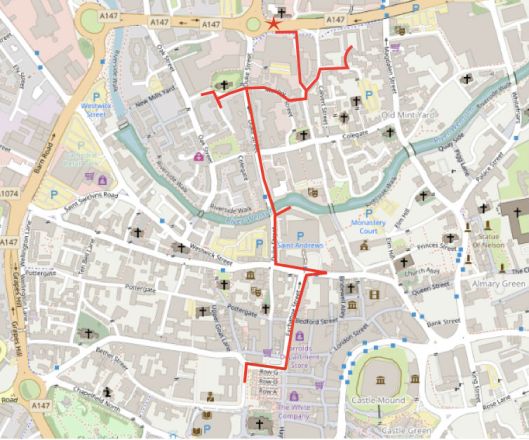

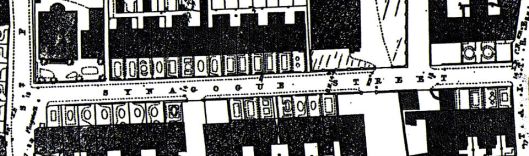

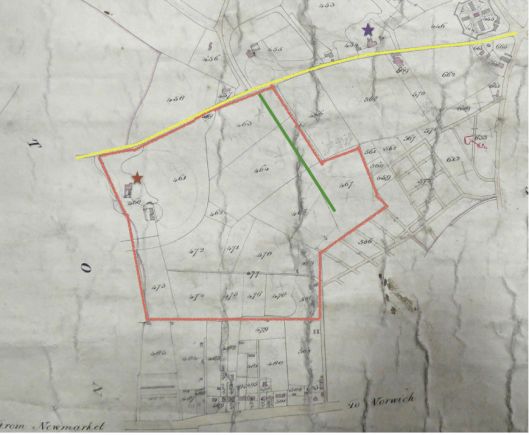

The Unthank Estate. This estate on the east side of Unthank Road was extensive, as the 1842 tithe map shows. By 1843, six years after his father’s death, Clement William Unthank was living outside the city at Intwood Hall. Now he started selling off his father’s estate and was applying to be excused land rent charges, “since the lands have been divided into numerous building plots.” First he sold Unthank’s House and two adjacent plots, then in 1850 he sold 46 acres 2 rods and 26 perches of surrounding land, followed in 1878 by another Certificate of Redemption of Rent Charge relating to the sale of his former garden, ‘The Lawn’ and ‘The Plantation’. This all goes to show that the Unthanks’ Heigham House was on this ‘Onley Street’ estate, outlined in red below, and not on land for which they held no title further down Unthank Road. The terraces subsequently built on Unthank land account for much of the Victorian housing on the east side of Unthank Road: from Essex Street to Bury Street.

Plots sold by CW Unthank 1843-1878. The octagonal gaol (top right) – now the site of the Catholic Cathedral – is at the city end of Unthank Road marked yellow. The Unthanks’ Heigham House is marked with a red star; Timothy Steward’s Heigham House with a purple star. The green line marks the future Essex Street and parallel to this were built Trinity, Cambridge, York, Gloucester, Onley and Bury Streets. Redrawn from the 1842 tithe map of Heigham (NRO BR276/1/0051). Courtesy of the Norfolk Record Office.

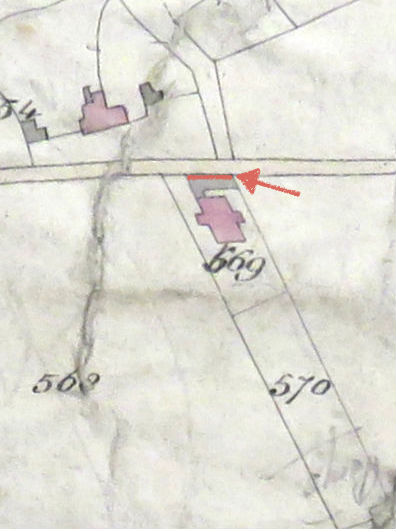

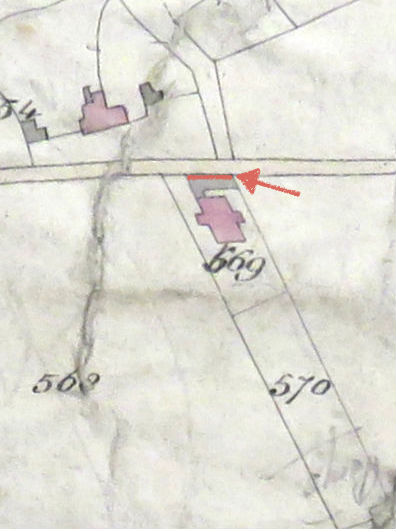

So who did own The Wall opposite Timothy Steward’s version of Heigham House further up Unthank Road? Again, the 1842 tithe map comes to our aid. The accompanying apportionment record gives the ownership of the numbered properties on the map. It shows that The Wall is on a strip of land belonging not to the Unthanks, nor to Steward, but leased to others by the Norwich Boys’ Hospital. This charity, founded by the C17 mayor Thomas Anguish, supported boys’ and girls’ hospitals by leasing their land around Norfolk.

The upper pink house is Steward’s, the lower is the Boys’ Hospital (occupied house in pink, outbuildings in grey). The arrowed red line marks the tall wall. From the 1842 Heigham tithe map. NRO BR2671/0051 Courtesy of the Norfolk Record Office

Account ledgers for the Trustees of the Norwich Boys’ Hospital, covering the years 1834-1897, are held in the Norfolk Record Office.

NRO N/CCH84. Courtesy of the Norfolk Record Office

The only entry for the parish of Heigham records that a house and garden of one acre, known as Peddars Acre, had been leased to Leonard Harmer for 60 years from Michaelmas 1822. This period is from 15 years before William Unthank died to 25 years after Clement William moved to Intwood. The land and its ‘messuage’ (buildings) were not, therefore, part of the Unthank estate and the absence of Clement William’s name from the ledgers rules out the remote possibility that he rented the stables from them after his father’s death.

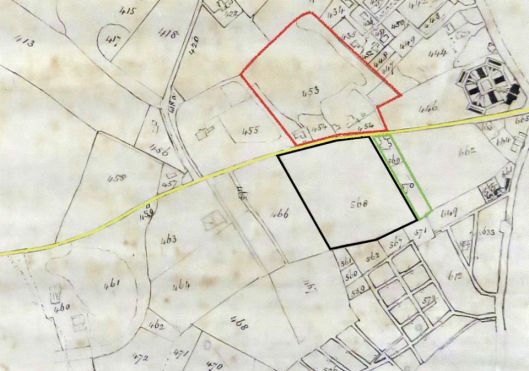

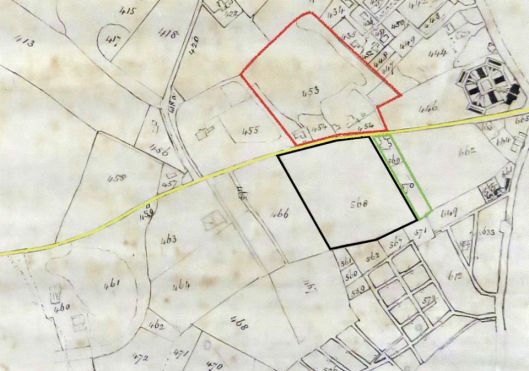

” (Where) every prospect pleases and only man is vile”. As to the unusual height of The Wall, Rosemary O’Donoghue [4], in her book on the C19 expansion of Norwich, mentions the steps that owners took to protect their privacy when breaking up their Heigham estates. Below, the 1842 tithe map of Heigham shows that Timothy Steward (whose house and grounds are outlined in red) owned another large plot of land, known as Home Close (black) on the other side of Unthank Road. This plot of arable land adjoined Peddars Acre (green) on one side and plot 466, which also belonged to Steward, on the other. Steward’s plots 453, 568 and 466 were almost as big as the Unthanks’ estate.

Steward’s house and grounds in red; Peddars Acre in green. He also owned plot 568 (black) and the adjacent plot 466. (Unthank’s House is #460 lower left). Redrawn from NRO PD522/44. Courtesy of Norfolk Record Office

The Victorian terraces of Trory, Woburn, Oxford and Kimberley Streets were to be built on Steward’s Home Close, plot #568. A purchase agreement dated 12th December 1853 (NRO N/TC/D1/277, 335 x2) refers to part of this land that William Trory (a tavern owner) had recently bought from Timothy Steward. The purchaser was required to:

“… build a good and substantial nine-inch brick wall, with 14-inch piers of the height of six feet … along the whole boundary of the said piece of land adjoining the garden ground of the said William Trory...”. [Trory leased Peddars Acre from 1837 to 1864]. The covenant continues, “And that no windows or other apertures shall be made in the said houses or buildings, or any of them (including those next to Unthank’s road) on the north-east side thereof, or so as to front or overlook the garden of the said William Trory.”

But in the original sale agreement with William Trory, Timothy Steward and his wife Lucy had gone to even greater lengths to limit what could be seen from their bedroom windows.

“… that before any offices or back premises of any description … shall be built on any part of the said land … a dwelling house facing towards Unthank Road and in a line to conceal such offices [an outmoded term for lavatory] or back-premises from being seen from the windows on the first-floor or first story (sic) of the residence of the said Timothy Steward“.

That is, the Stewards made sure that even if William Trory re-sold the land, as he did, the purchaser’s first legal duty would be to build an entire house facing the Steward residence so that their gaze should not alight on lavatories or other outhouses on the other side of the road. As a consequence, Trory Street is a cul-de-sac, blocked from opening directly onto Unthank Road.

Opposite Steward’s house

Furthermore, the Stewards had specified that nothing unsavoury should be seen, not just from their garden, but from their bedroom windows! A six-foot wall of the kind that Trory had demanded around his own garden could not have met this stringent condition but the Stewards’ sensitivities provide an explanation for the twelve-foot wall that separates the building on Peddars Acre from Unthank Road.

©2017 Reggie Unthank

The book, “Colonel Unthank and the Golden Triangle”, contains much more than is included in my three posts on the Unthanks. It also contains fascinating photographs of the Unthank family, not seen online. Still available from Jarrolds Book Department, and The City Bookshop in Davey Place, Norwich. Or contact me direct.

Book available from Jarrolds Book Department and City Bookshop £10

Sources

- Nixseaman, A.J. (1972). The Intwood Story.ISBN 0950274208, Norwich. (Available from the Heritage Centre, Norwich Library)

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/04/15/colonel-unthank-rides-again/

- Rye, Walter (1917) History of the Parish of Heigham in the City of Norwich. A digitised version is on http://welbank.net/norwich/hist.html#hhall

- O’Donoghue, Rosemary. (2014). Norwich, an Expanding City 1801-1900. Pub, Larks Press ISBN 9781904006718.

Thanks. I am enormously grateful to the staff of the Norfolk Record Office for their help and advice in searching the records and for giving permission to reproduce images.

![Exchange St Corn Exchange west side [2513] 1938-06-26.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/exchange-st-corn-exchange-west-side-2513-1938-06-26.jpg?w=529)

![Coslany St Bullard's fermentation hall [5342] 1973-01-05.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/coslany-st-bullards-fermentation-hall-5342-1973-01-05.jpg?w=529)

![Belvoir St Wesleyan Reform Methodist church [6585] 1989-09-18.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/belvoir-st-wesleyan-reform-methodist-church-6585-1989-09-18.jpg?w=529)

![Orford Hill 8 [2707] 1938-08-13 A.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/orford-hill-8-2707-1938-08-13-a.jpg?w=529)